All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Paranormal Health Beliefs: Relations Between Social Dominance Orientation and Mental Illness

Abstract

Background:

Illusory beliefs are false beliefs that fulfill the function of creating a “filter” through which reality acquires order and meaning. Even though many studies have been conducted on this topic, there have been few investigations into the role illusory beliefs play, as specifically related to health concerns.

Objective:

The current research takes up the objective of investigating the relationships between paranormal health beliefs (with specific reference to pseudo-scientific beliefs of a bio-medical nature), social dominance orientation, god-centered health locus of control, and coping by turning to religion, as well as their predictive role with respect to mental illness.

Methods:

432 adults (76.8% women) were contacted, with a median age of 24.9 years (DS=11.6). A self-report questionnaire, composed of various instruments, was administered to the participants. The questionnaire consisted of the following instruments: Paranormal Health Beliefs Scale, Social Dominance Orientation, Health Locus of Control Scale, Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced and General Health Questionnaire. Descriptive and correlational analyses were performed, along with structural equations modeling.

Results:

Based on the analyses conducted, it emerged that social dominance orientation and the god-centered health locus of control are antecedents for pseudo-scientific beliefs of a bio-medical nature, which, in turn, affect coping by turning to religion. Coping by turning to religion predicts perceived illness.

Conclusions:

These results provide a useful direction for understanding the factors that influence the health decisions of individuals and, therefore, must be taken into consideration even in the most diverse health contexts.

1. INTRODUCTION

Health is a complex condition which implies the integration of multiple realms: the biological, psychological, and social, as well as the intervention of many different social actors (individuals, associations, organizations, and institutions), which are involved in the definition and realization of various goals, from prevention to education and promotion [1]. This concept of health has inspired the “bio-psychological-social model of health” [2], which considers people to be active subjects who draw upon a complex system of material, cognitive, emotional, and relational resources [3, 4], and which considers the individual’s assumption of responsibility for their own health to be a central theme in the realm of health promotion. In this way, then, conditions are created in which individuals can become oriented towards choices that consciously and positively impact their own well-being. Among the many psychological dimensions involved in this process, one relevant role is played by illusory beliefs related to health. Therefore, it seems important to deepen our understanding of the ways in which people position themselves with respect to illusory beliefs, with the aim of understanding how these beliefs might operate when people find themselves in need of addressing questions concerning their health. More specifically, a particular type of illusory belief will be investigated in this study: pseudo-scientific beliefs of a bio-medical nature, which hide under the guise of science and reproduce some of the mythic aspects typical of conservative ideology. They are resistant to change and anchored in tradition. We will investigate the possible antecedents of this typology of beliefs and try to understand their role in strategies for dealing with stressful situations and ill health.

1.1. Paranormal Beliefs and Health

In the literature, illusory beliefs are also defined as beliefs in the paranormal [5, 6]. Phenomena that can be included in the realm of the paranormal are very diverse, and the definition of paranormal belief itself has been revised many times, with regard primarily to the following points: 1. that which cannot be explained in terms of contemporary science; 2. that which can be explained only by significant revisions of limiting and fundamental scientific principles; 3. incompatibility with normative perceptions, beliefs, and expectations about reality [7, 8, 5]. Therefore, it is a complex construct and one that is difficult to operationalize; however, for many years already, there has been a scholarly consensus that it is a multidimensional construct. Tobacyk [8, 9] has individuated the following dimensions: Traditional Religious Belief, Psi, Witchcraft, Superstition, Spiritualism, Extraordinary Life Forms, and Precognition. The relationship between paranormal beliefs and health has been investigated in several studies, which have found the existence of a significant and positive correlation with mental illness [10] and with manic-depressive experiences [11]. However, contradictory results have been found with respect to the relationship to neuroticism [12, 13] and anxiety [14, 15]. Other studies have found that some types of beliefs (eg., religious and fatalistic beliefs) may inhibit the utilization of healthcare and healthcare-related behaviors [16, 17]. More recently, illusory beliefs have been considered in the literature, specifically in relation to the sphere of health [4, 18], such as the beliefs and practices of timely healing, disease prevention, and the general promotion of health. In the case of paranormal beliefs related to health, several other dimensions have already emerged from more general studies of beliefs in the paranormal, such as Religious Beliefs, Superstitious Beliefs, Extraordinary Events Beliefs, and Parapsychological Beliefs. However, another dimension also appears: that of Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs of a Bio-Medical Nature, which refer to the negative impact on human health of specific categories considered socially deviant or marginal (homosexual, immigrant) and to the threats to health posed by hereditary transmission or genetic contamination (interracial relationships). In these studies, it has been shown that these specific beliefs are positively associated with general illusory beliefs, thereby not only those related to health; furthermore, they are also positively associated with an external health-related locus of control, and negatively associated with the internal health-related locus of control. With respect to sex-based differences, men, both adolescents and adults, have more confidence in medicine as a science and have a tendency to rely on a bio-medical approach in relation to the protection of the species, while adult women have higher levels of religious beliefs [4, 18].

From a social-cognitive perspective, the function of illusory beliefs is fundamentally adaptive; in fact, Taylor and Brown [19], in speaking about the relationship between health and the paranormal, suggest the idea of the self-serving illusion, emphasizing that illusory beliefs, even as they are definitively false beliefs, serve an important function for mental health by creating a “filter” through which reality acquires order and meaning. Grimmer and White [20] have also demonstrated the relevance of such belief systems for adaptation in the realm of health and illness, with specific reference to various dimensions.

From a psycho-dynamic point of view, instead, Irwin [21] has formulated the psychodynamic functions hypothesis, which sees belief in the paranormal on par with a coping strategy, like that of avoidance, which occurs in the treatment of post-traumatic stress.

1.2. The Paranormal Beliefs and Connections to Other Constructs

1.2.1. Coping Strategies

A fundamental role is given to adaptation when it comes to defining well-being. By adaptation, one refers to the coping strategies that people access in order to maintain a sense of well-being, and to reclaim their well-being after stressful events [22]. The importance of coping strategies has been demonstrated by many studies, inspired by different theoretical models; scholars, however, do not fully agree on what significance to attribute to these strategies, and to the mechanisms by which they influence well-being [23]. Coping refers to the combined cognitive efforts and behaviors put forth to control specific internal or external requests that appear to exceed a person’s resources [24]. One of the most noted approaches is that developed by Lazarus and Folkman [25], who distinguish between two styles of coping: problem-focused and emotion-focused. From this framework, the two authors develop a preliminary measure called the Ways of Coping Checklist [26], but in the years since, other instruments [27, 28] have been developed with the goal of expanding the available range of coping strategies. The goal is to be able to measure, with greater precision and completeness, the modalities with which people confront problematic events.

Taken together, there are not many studies on the relationship between illusory beliefs and coping styles/strategies, and the question of the adaptive or maladaptive nature of illusory beliefs (when considering health) is still open to some controversy, thanks to its multidimensionality, among other things. Subjects who claim to believe in the paranormal tend to avoid confronting problems directly; they prefer to negate or to find refuge in fantasy, distracting themselves rather than dealing with emotional distress [29]. Therefore, they have recourse to a passive form of coping. At the same time, however, according to other authors, belief in paranormal phenomena could be used by subjects to create a sense of control over unpredictable events [30]. Those who believe in these phenomena tend to reformulate negative life events, such as serious physical abuse, in terms of supernatural processes in an attempt to explain, and therefore come to terms with, a painful life event [31]; they have recourse to an active-cognitive coping strategy. Similar mechanisms have also been defined as the basis for various religious coping strategies [32], both positive and negative [33]. Positive religious coping consists of turning to religion to free oneself from fear, anger, and sin, to seek comfort and reassurance from members of the religious community and the clergy, and to engage in religious activity in order to shift focus away from stressful events. This form of coping is correlated with greater psychological well-being, a lesser experience of depression, anxiety, and distress, greater spiritual growth, positive affect, and self-esteem. In contrast, negative religious coping consists of redefining stressful events as acts of the Devil or as punishment by God for one’s sins, passively waiting for God to manage the situation, and indirectly seeking control over events through pleas to God for a miracle or divine intervention. This form of coping, in the majority of cases, can have damaging effects on the well-being of individuals, because it leads to a disavowal of responsibility and, therefore, it is positively correlated with uneasiness and an external locus [34, 35].

1.2.2. Locus of Control

Among the psychological determinants that can impact the well-being/ill health of individuals, a central role is played by the locus of control [36, 37]. That is, a role is played by the representations that individuals have of what causes events in their lives, and what causes the status of their health (health locus of control). Understanding the origin of one’s own health as rooted in individual behaviors (internal causes) means giving a greater weight to one’s own will, engagement, and responsibility [38, 39]. This, in turn, positions one in relation to a binary, the opposite end of which is to attribute one’s health to unknown and unforeseen factors (supernatural forces), or to the diagnosis of experts (external causes). Subjects with an internal locus of control are more sensitive to messages related to health, better understand their own condition, and try to improve their health, succeeding in many cases at being less susceptible to physical and psychological threats [40].

Studies have shown that people who believe in the paranormal generally have a greater tendency to an external locus of control [8, 41-43], even if other authors [44, 45] do not recommend considering global measures of locus and paranormal beliefs, because the strength and indication of the relationship between the two constructs can vary, based on the type of belief. More specifically, superstitious beliefs, because they implicate a lack of control, are correlated with an external locus of control, while psychological beliefs, because they implicate a more active personal role, are more correlated with an internal locus.

1.2.3. Tendency Towards Social Dominance

One relationship that, in contrast, has not to our knowledge been investigated in the literature is that of the relationship between illusory beliefs and the construct of social dominance. The Social Dominance Orientation reemerges in Social Dominance Theory, according to which a large portion of social conflict is the result of societies’ organization into hierarchies based on membership in socially-constructed groups [46, 47]: gender, age, ethnicity, nationality, and religion. It is a personality variable which brings people to desire their own social category, one superior to others to the point of dominating them. Social dominance is a strong predictor of the Legitimizing Myths of inequality [47]: attitudes, values, beliefs, stereotypes, and ideologies that offer “a moral and intellectual justification for the practices that allocate social values in an asymmetrical manner among groups” (p. 194) [48]. Thus, they accord with the legitimation of social stratification. The Legitimizing Myths of inequality are born, or reactivate themselves, particularly in times of changing social values and established traditions: among these myths, for example, we find the myth of biological identity and genetic purity, found in fascist ideology [49]. People with high levels of social dominance tend [48] to formulate internal causal reasons for inequality, to support policies that do not reduce inequality, and to uphold merit as the criterion for allocating resources. They are opposed to women’s and to gay and lesbian rights, to universal healthcare and to other systems of welfare, to immigration and integration, and they support the death penalty. Therefore, those who have high levels of social dominance have a more conservative attitude with a greater attachment to tradition, a resistance to change, and a rejection of ambiguity [46]. Conservative ideology correlates with preferences, attitudes, and behaviors that go well beyond the right-left binary of the political spectrum, going so far as to assert that humans are ideological animals in many different areas of consideration [50, 51].

1.3. The Current Research

Considering the role that illusory beliefs can have in the behavioral choices of individuals, the first objective of the present study is to investigate the relationship between Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs of a Bio-Medical Nature and Social Dominance Orientation, as well as with the God-Centered Health Locus of Control, Coping by Turning to Religion, and Mental Illness. We have hypothesized the existence of positive interrelationships among Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs of a Bio-Medical Nature and God-Centered Health Locus of Control, Social Dominance Orientation, Coping by Turning to Religion, and Illness.

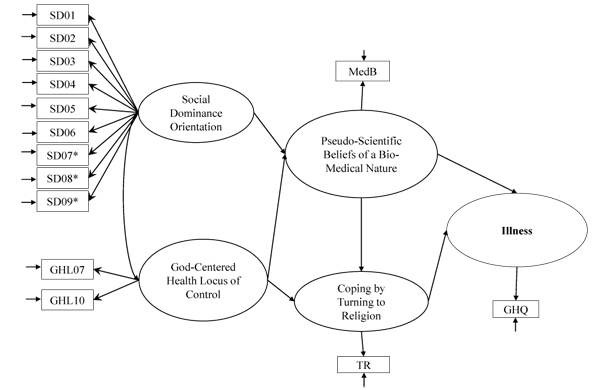

Furthermore, in the perspective of developing pscyho-educational intervention programs that could raise awareness of the socio-cultural aspect of these beliefs, the second goal is understanding the role of personality variables (Social Dominance and Locus of Control) with regard to Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs and their function, as well as turning to religion coping in relation to perceived Illness. More specifically, as far as the determining factors of illness, which are considered an outcome variable, we have hypothesized a model (Fig. 1) in which: Social Dominance and God-Centered Health Locus of Control have been inserted as antecedents of Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs of a Bio-Medical Nature; God-Centered Health Locus of Control and Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs are considered predictors of Coping by Turning to Religion; and Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs and Coping by Turning to Religion are predictors of Illness. We hypothesize, furthermore, that the relation among the variables as relates to the religious realm could be different for religious believers (Catholics) and atheists.

2. METHOD

2.1. Participants and Recruitment Procedure

A convenience sample of people hailing from Southern Italy was obtained, composed of 451 people. 19 subjects were eliminated, as they declared belief in a religion other than Catholicism. The 432 participants in the study were mostly female (76.8% female; 23.2% male), with ages ranging between 18 and 70 years (M = 24.9, SD = 11.6). 66.2% of the participants were Catholic and 33.8% were atheist. 57.0% of the participants have a center-left political orientation, 28.9% center, and 14.1% have a center-right political orientation.

Participation in the study was voluntary and anonymous, and participants were encouraged to answer as truthfully as possible. Furthermore, all the study participants provided written informed consent.

2.2. Instruments

Making use of a quantitative methodology, a questionnaire, including validated instruments in the Italian language, was specifically designed for the study.

Paranormal Health Beliefs Scale [4, 18]. For the current study, we used the following sub-scale for Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs of a Bio-Medical Nature, which refer to beliefs regarding the negative contribution to the health of the human species of specific categories that are considered to be deviant or marginal social groups, and to health threats deriving from hereditary transmission or genetic contamination (ex., “Persons affected by generational evil constitute a threat for the health of the human species” and “Relationships between people of different races may be harmful to health”; α = 0.65). Each sub-scale consists of 4 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 5 = “Strongly Agree”): high scores relate to high levels of illusory beliefs referring to health.

Social Dominance Orientation Scale [46, 48], assesses the preference for inequality among social groups and the superiority of some people over others, with 16 items such as “Some groups of people are simply inferior to other groups,” and “No one group should dominate in society.” All items were measured on a 7-point Likert scale, anchored at “Strongly Agree” and “Strongly Disagree.” Higher scores indicate higher levels of SDO. The scale had an internal consistency coefficient of 0.73.

Health Locus of Control Scale [42, 43]. For the current study, we used the following sub-scale of the God-Centered Health Locus of Control scale for the measurement of the religious orientation of locus of control as related to health (ex., “If God wants, my physical health can improve” and “My physical health can be safeguarded with God's help”; α = 0.89). Each sub-scale consists of 2 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (from 1 = “Strongly Disagree” to 5 = “Strongly Agree”). Higher scores indicate higher levels of Locus of Control.

Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced [28, 52]. For the current study, we used the following sub-scale of the Turning to Religion scale (ex., “How often do I try to find comfort in my religion?”, and “How often do I look for help in God?”; α = 0.96). Each sub-scale consists of 4 items rated on a 6-point Likert scale (from 1 = “I never do that” to 6 = “I always do that”). Higher scores indicate higher levels of coping strategies.

General Health Questionnaire [53, 54] is aimed at detecting nonpsychotic psychiatric morbidity in the general population (ex., “Have you recently been able to concentrate on whatever you’re doing?”, and “Have you recently been able to enjoy your normal day to day activities?”). The scale consists of 12 items rated on a 4-point Likert scale rating (from 1 = “Not at all” to 4 = “Much more than usual”), distinct in: Somatic Symptoms and Social Dysfunction. For the purposes of this study, the overall scale score was considered. Higher scores indicate greater levels of general psychiatric distress. Internal consistency reliabilities have been found to be 0.86.

Finally, the questionnaire included a section for the collection of socio-demographic data (gender, age, religion, and political orientation). Each questionnaire took approximately 30 minutes to complete.

The study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee, and the study was conducted according to APA ethical standards. The study conformed to the ethical principles of the 1995 Helsinki Declaration.

2.3. Statistical Analyses

In order to calculate the reliability of the scales, we used Cronbach’s alpha. An internal consistency greater than .70 is thought to be necessary for the psychological scale, even if an alpha between 0.60 to 0.69 would be considered acceptable [55].

We used descriptive statistics to analyze the characteristics of the respondents and the study variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used to determine the relationship between all the variables (p-value < 0.05). Finally, Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was used to test structural relationships. Goodness-of-fit of the model was assessed as indicated by a chi-squared distribution and the degrees of freedom (χ2/df ≤ 3), a Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR ≤ 0.08), Comparative Fit Index (CFI > 0.90), and Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI > 0.90). Results of the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) are considered to be good if they are ≤ 0.05 and reasonable if they are ≤ 0.08. Because the different indices assess different aspects of goodness-of-fit, evaluating multiple fit indices simultaneously is recommended [56-58]. Satisfactory models should show consistently good-fitting results on many different indices.

Survey data were then entered into SPSS 18.0 [59] and Lisrel 8.54 [60] databases and checked/verified by project staff for accuracy.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Means, and Standard Deviations and Correlations

Means, Standard Deviations, and correlations are shown in Table (1). The results for zero-order correlations between the instruments indicate that Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs are not correlated with Illness, but are highly positively correlated with Social Dominance Orientation (0.31**), Coping by Turning to Religion (0.23**), and God-Centered Health Locus of Control (0.16**). Indeed, Illness was highly positively correlated only with Social Dominance Orientation (0.10**) and Coping by Turning to Religion (0.10**).

| Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs of a Bio-Medical Nature | 1.42 | 0.58 | 1 | ||||

| 2. God-Centered Health Locus of Control | 2.36 | 1.24 | 0.16** | 1 | |||

| 3. Coping by Turning to Religion | 2.38 | 1.66 | 0.23** | 0.70** | 1 | ||

| 4. Social Dominance Orientation | 2.66 | 0.88 | 0.31** | 0.09 | 0.13** | 1 | |

| 5. Mental Illness | 2.88 | 0.55 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.10* | 0.10* | 1 |

3.2. Testing of the Hypothesized Conceptual Model

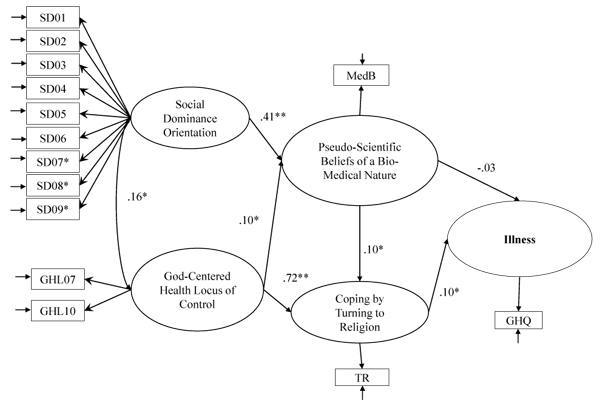

We used structural equation modeling to test the structural relationships. The hypothesized model for predicting illness was tested Fig. (2) and the results confirmed our model, with good fit between the theoretical and the empirical models: χ2(df) = 184.30(71), p = n.s.; χ2/df = 2.59; CFI = 0.94; NNFI = 0.92; RMSEA = 0.06 [0.05, 0.07]; SRMR = 0.07; GFI = 0.94; AGFI = 0.91. As hypothesized, Social Dominance is a strong predictor of Paranormal Health Beliefs along with External Locus of Control, which is a very strong predictor for coping by turning to religion. In turn, Coping by Turning to Religion is also predicted by Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs which, however, do not predict Illness, upon which only Coping by Turning to Religion has bearing.

Note: *p < .05; **p < .01.

Furthermore, the model was tested separately on Catholics and atheists. Applying the model only to Catholics (N= 286), the relations between the variables are confirmed, and the model as a whole shows good indices of fit:: χ2(df) = 124.12(71), p = n.s.; χ2/df = 1.75; CFI = 0.95; NNFI = 0.93; RMSEA = 0.05 [0.04, 0.07]; SRMR = 0.06; GFI = 0.94; AGFI = 0.91. Applying the model only to atheists (N= 146), the indices of fit are not satisfactory: χ2(df) = 138.42(71), p = n.s.; χ2/df = 1.94; CFI = 0.82; NNFI = 0.78; RMSEA = 0.08 [0.06, 0.10]; SRMR = 0.11; GFI = 0.88; AGFI = 0.82.

4. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

The results confirmed our hypotheses, relative to the relationships among the variables of interest. Paranormal Health Beliefs are positively associated with Social Dominance Orientation and, in line with the literature, also with God-Centered Health Locus of Control and Illness.

In particular, the noted interrelationship between Social Dominance and Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs of a Bio-Medical Nature is emphasized, as well as the predictive role of Social Dominance with respect to these beliefs. These results lead us to consider paranormal health beliefs as part of the Legitimizing Myths that, according to Social Dominance Theory, bring individuals to value their own vision of social relations (both interpersonal and intergroup) as hierarchically structured and conflictual. These results are compatible with those demonstrated in the studies on Group Based Dominance [61, 62], which showed a positive correlation with the tendency toward Social Dominance, and particularly with the sub-dimension of Group Based Dominance, which is related to support for social dominance based on group membership. Group Based Dominance beliefs are essentialist, common-sense ideas about social categories and serve as justification for the social order. Today, these theories take up pseudo-scientific and ideological approaches, which also prevailed in the fascist era, as common-sense ideas [63] which are shared even by those in the modern era who lean towards conservatism. It has been observed that, today, it is improbable to maintain, as it was in the past century, the ‘myth’ that the hegemony of one group over others is the direct expression of a divine will [64]. The religious basis of conservative ideologies and social stereotypes has been substituted at least in part by more modern and plausible explanations for the differences between groups and the predominance of some over others; these explanations come from science and, more specifically, genetics [62]. The results also lead us to reflect on the negative consequences of an individual’s tendency toward dominance: if this tendency does not seem to directly impact psycho-social well-being, it may do so, negatively, in the case of shared bio-medical beliefs about health.

Pseudo-Scientific Beliefs of a Bio-Medical Nature are associated, furthermore, with Coping by Turning to Religion. Therefore, one turns to a concept of divine will in order to confront health problems, putting faith in God alongside a quasi-magical intervention by the doctor-miracle worker, and medicine as a technical-scientific tool [4]. This association can be interpreted as disproving the hypothesis formulated by Rogers and colleagues [65], on the coping function of paranormal beliefs. Coping by Turning to Religion, in turn, resulted as a predictor of Illness: therefore, it seems that Coping by Turning to Religion, if supported by paranormal beliefs, figures as a passive, negative strategy that can lead to a state of ill health.

The relations described here are specific to those who believe in the Catholic religion and who are not atheists. This data is interpreted with confidence thanks to the specificity of the instruments being used, and requires further exploration and confirmation in the future.

In light of the results of this study, it seems relevant to deepen our understanding of the way in which people position themselves with respect to that grouping of beliefs that concern the paranormal realm, and which can be operative in the moment one must confront health-related problems, influencing an individual’s approaches, expectations for results, and the practice of harmful behaviors.

4.1. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study has several limitations. First, we must consider the relatively small number of participants and the limited territorial origin of the participants, as well as the lack of diversity in terms of demographic characteristics (sex and political orientation). Further limits include the cross-sectional characteristics of study and self-report data.

In the future, a longitudinal study should be envisaged with the involvement of a greater number of participants, balanced in terms of gender and political orientation, and coming from different territorial contexts. Furthermore, future investigations could integrate quantitative with qualitative data.

In the future, further studies would be advisable if they could verify the hypothesis of the mediational role of paranormal health beliefs in the relation between social dominance and illness. It would also be useful to deepen understanding of the relationships between pseudo-scientific beliefs of a bio-medical nature and other beliefs, such as belief in genetic determinism. We would also advise studies on the predictive role of pseudo-scientific beliefs of a medical nature regarding support for, or opposition to, welfare policies, and studies on the relationship between social dominance and well-being, taking into account the sub-dimensions of well-being (especially social well-being).

Finally, it would be interesting to test this model on groups who have been differentiated by types of religion and participation in religious activities, along with a further understanding of the existence of these relationships in specific social categories such as teachers [66, 67] and doctors [68], for the effects that their ill health may have on students and patients.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study protocol was approved by the Local Ethics Committee, and the study was conducted according to APA ethical standards. The study conformed to the ethical principles of the 1995 Helsinki Declaration.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals were used in this research. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All the study participants provided written informed consent.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.