All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Risk of Internet Addiction in Adolescents: A Confrontation Between Traditional Teaching and Online Teaching

Abstract

Background:

The technological evolution has given the opportunities to develop new models of education, like online teaching. However, Internet Problematic Use and Internet Addiction are becoming frequently represented among adolescents with a prevalence that varies worldwide from 2% to 20% of the high school population.

Objective:

The aim of this study was to analyse the risk of Internet Addiction in a High Schools student sample comparing two different types of schools (online and traditional teaching) and analyzing the associations between pathological use of Internet and socio-demographic factors connected to the different educational orientations and to the daily usage of Internet.

Methods:

Students were enrolled from four different orientation school programs (different high school, technical and economical Institute, vocational schools). Each student completed a self-reported test to collect socio-demographic data and th Internet Addiction Test (IAT) from K. Young to assess the risk of Internet Addiction. The Mann-Whitney test for quantitative variables was used for statistical analysis.

Results:

522 students were enrolled, 243 students from online teaching and 279 from traditional teaching schools. Internet Addiction was observed in 1,16% of the total sample, while 53.83% of subjects was at risk of development Internet Addiction. No significant difference was found between the two different types of teaching, nor considering gender. Considering the amount of time spent on the web in portion of the sample at risk of developing Internet Addiction, the Traditional Teaching group spent between 4 and 7 hours a day on the Web, while the Online Teaching group between 1 to 3 hours/daily. However, no statistically significant difference was found.

Conclusion:

Although our data demonstrate that there is no clear association between online education and problematic use of Internet, the excessive use of Internet is linked to a massive waste of personal energy in terms of time and social life.

1. INTRODUCTION

New technologies, when used appropriately, undoubtedly constitute a tool able to greatly improve the quality of an individual’s life. The widespread of Internet is probably one of the biggest revolutions of the last few years. It changed the way of communicating, exchanging information, participating in real-time events even at thousands of kilometres away, and finding easily and rapidly any kind of information [1, 2].

Especially over the past decade advances in technologies have allowed a seamless and ubiquitous connection of individuals to the online world, thus being the key driver of a phenomenon called Internet Addiction Disorder (IAD) [3]. IAD may be considered a behavioural addiction that can be defined as “an excessive use of the Internet that creates psychological, social, school, and/or work difficulties in a person’s life” [4]. In particular, according to different psychopathological models, IAD can be considered as a mix of typical features of addiction, Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and impulse control disorders. Moreover, several studies show possible withdrawal symptoms such as seen in other addictions [5, 6].

Psychiatry is beginning nowadays to acknowledge IAD as a candidate mental disorder [7], as shown by the inclusion of Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) in Section III of the DSM-5 as a condition for further study [8]. In fact, many Internet related behaviours, such as excessive video gaming, pornography viewing, buying, gambling, or streaming and social networks use have been associated with marked functional impairment including loss of productivity or reduced scholastic achievement and mental health sequelae, such as mood and anxiety disorders [9, 10].

In the last twenty years, IAD has become a worldwide health issue. For example, in European countries, studies reported that about 1 to 8% of adolescents aged between 11 and 18 years old have developed a Pathological Use of the Internet (PUI) or, when the impair on social, working, and school functions is bigger, IAD [11]. PUI is defined as “all potentially problematic Internet related behaviours, including those relating to gaming, gambling, buying, pornography viewing, social networking, ‘cyber-bullying,’ ‘cyberchondria’, among others” [12]. The international interest upon PUI is increasing nowadays because of the mental and physical health consequences that may lead to the addiction itself [12].

The prevalence of IAD and PUI varies across countries. In a study conducted on students from Singapore, Mythily et al. reported that 17.1% of 2735 adolescents (mean age of 13.9 years) used more than 5 hours of Internet, everyday [4]. In a recent study about Southern Italy High School students [13], IAD prevalence was 3.9%, with males showing a higher likelihood of developing pathological Internet use. Moreover, the results of this study confirm the role of experts dealing with addiction to implement programs for primary and secondary intervention among high school students [13]. In fact, IAD often starts in childhood or adolescence, with young people typically having problems with gaming and media streaming; in particular, young males tend to use the Internet for gaming, gambling, and viewing pornography, while young females for social media and online shopping [14].

Among the opportunities and advantages offered by the Internet, there is the possibility of using it for online teaching. Online teaching school programmes are characterized by the use of a multimedia interactive blackboard; each student has a personal tablet which is used to consult books and learning material and that can connect, via Wifi, to Internet. In digital schooling, teachers also use electronic devices, such as computer and tablet, and digital platform to provide lessons and exercises. Every course is conducted via computer and Internet and it is also possible to perform virtual classrooms.

The spread of online teaching raised questions about the possibility that using Internet in schools could create impairment in students’ life, or at least increase the risk of developing PUI or IAD. Moreover, it is fundamental to understand the impact of the consistent use of Internet and the consequentially possible disorders on school performances, considering the Internet use as a learning instrument. This is an area where literature is currently still lacking and it deserves further investigation. In fact, the results of a group of studies that have examined the direct relationship between IAD and academic performance have been mixed [15-18].

To our knowledge, this is the first study that compares traditional teaching and online teaching in order to evaluate if the use of Internet in this field may be directly linked to an increased presence of PUI or IAD.

Considering the above, the principal aim of this study is to analyze the risk of PUI or IAD comparing two different teaching models, Online Teaching (OT) and Traditional Teaching (TT). In fact, the consistent use of Internet for any school task may facilitate the onset of IAD or PUI in adolescent students, a specific population well-known for being at risk of developing any form of addiction [19] and in particular Internet-related disorders, such as Online Gaming Disorder [20]. In addition, we would like to improve our knowledge about the associations between pathological manifestations of IAD or PUI and sociodemographic factors connected to the different educational orientation and to Internet daily usage among the students. The present study evaluates young people around the age of 16, at a stage of transition from puberty to adulthood.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

The students enrolled in our study were selected from four different High Schools, in a region of Northern Italy (the Lombardy region). At the time of the evaluation, all students were attending third classes from different orientation school programs (vocational school, technical institute, art/sports high school, and economic/commercial institute). Students who attended online schools (OT) were recruited at the beginning of 2018, while students from traditional schools (TT) were recruited between the end of 2018 and the beginning of 2019. All students were aged between 15 and 19 years old. Mental Health experts (psychologists and psychiatrists) trained the teachers who administered the assessment tools and instructed the students about how to fill them.

2.2. Materials

To collect socio-demographic data, a self-reported test consisting of nine items was given to all students to investigate age, nationality, sex, type of school, orientation of the school (professional, technical, commercial, or high school), the principal use of Internet, and the amount of time dedicated.

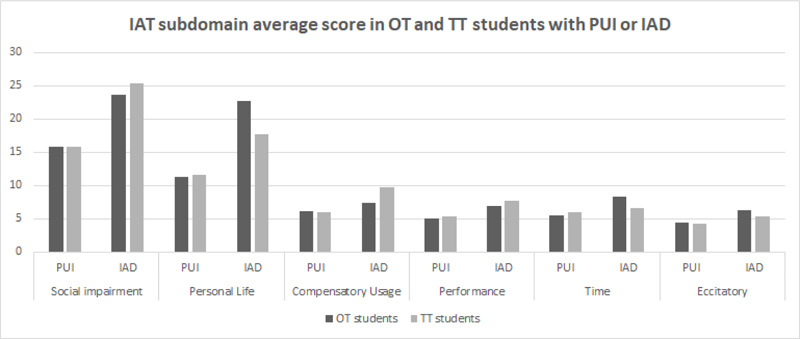

To assess the risk of IAD, the Italian version of the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) by K. Young (1998) was used: IAT is a self-assessment scale consisting of 20 items that quantitatively estimate the connected risk of excessive and problematic use of the Internet, also considering the working and social dysfunctions. The IAT score can vary from 0 to 100, and is divided into three cohorts: A score between 0 and 39 shows a normal use of the Internet; between 40 and 69 it is possible to assess the presence of a Problematic Use of Internet (PUI), which is linked with higher risk of developing IAD; a score above 70 (70-100) is linked with IAD. Moreover, considering each of the 20 items assessed in this test, it is possible to deduce which area of a person’s life is more compromised by the pathological use of the Internet. For this reason, six sub-dimensions were identified: 1) Compromised social quality of life [items 4, 5, 9, 13, 16, 18]; 2) Compromised individual quality of life [items 2, 12, 14, 19, 20]; 3) Compensatory usage of Internet [items 7, 11, 15]; 4) Compromised academic performance [items 6, 8]; 5) Compromised time control [items 1, 17]; 6) Excitatory usage of the Internet (items 3, 10). The internal reliability of the IAT has been found to be between 0.90 and 0.93 [21, 22].

2.3. Data Collection Procedure

All students’ parents were informed about the study modality and aims and were provided written informed consent to permit submission and collection of the questionnaire for research purposes. The study project (with attached material) was sent, explained and examined by each of the schools’ principals. Teachers were then instructed about the aim of our study and the questionnaires. Teachers also arranged the distribution of the information sheet and the material indicated above; the administration of the surveyed questionnaires was anticipated by an explication of aims. The authors collected data in an anonymous database.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted with SPSS software version 19. Descriptive analyses were calculated using frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and Standard Deviations (SDs) for continuous variables. The data did not show a gaussian distribution. Hence, the Mann-Whitney test, as a non parametric test, was used to perform the statistical evaluation.

3. RESULTS

The study sample consisted of 522 students. The total sample was then dichotomized, depending on teaching methods, in Online Teaching (OT) and Traditional Teaching (TT). Online Teaching uses Personal Computers and the Internet as instruments to teach and to learn, while Traditional Teaching is characterized by the use of learning instruments like books and other written materials. The study was conducted in the first semester of 2018 in digital teaching schools and at the end of 2018 and the beginning of 2019 in traditionally oriented schools. 243 OT students (46.55%) were recruited, 53.51% in a vocational school; 32.92% of an art / sports high school and 13.17% of an economic/commercial institute. Instead, 279 TT students (53.45%) were enrolled (43% boys and 57% girls), 28.67% belonging to a vocational school; 12.55% for a technical institute; 7.17% at an art / sports high school; 47.67% at a scientific / linguistic high school and, finally, 3.94% at an economic / commercial institute. The total sample average age was 16.72 years (± 0.6), while it was 16.29 years (±0,52) and 17.15 years (±0.68), respectively, in OT and TT subgroups.

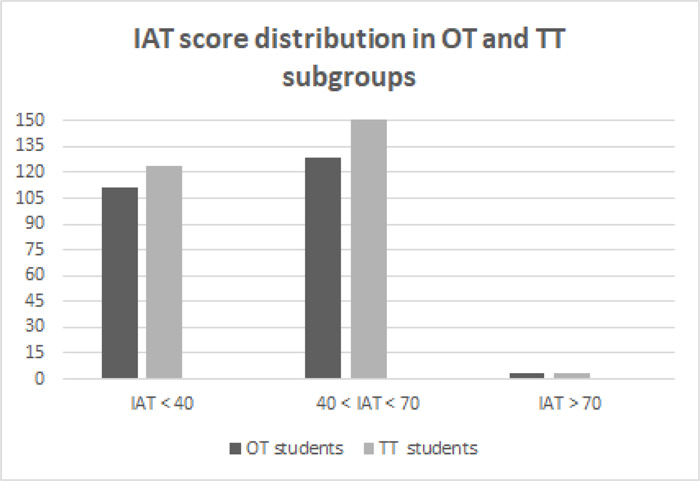

As showed in Fig. (1), in the whole sample, only 1.16% students exceed the cut-off of 70 in IAT score, and 53.83% of the subjects were found to be at risk of development of IAD (IAT score from 40 to 70; mean IAT=41.81, DS= 9.95). Most of these students were part of OT (mean IAT=41.41, DS= 9.80). In particular, three OT students (1,20%) had scored more than 70 points and 129 OT subjects (53,30%) showed a score between 40 and 70. In TT group (mean IAT=42.17, DS= 10.08), three students (1,20%) had more than 70 points, while 152 students had more than 40 points(54,50%).

In this regard, through the Mann-Whitney test, no significant differences were detected between the two types of teaching. Therefore, using Internet in teaching methods does not seem to increase the risk of developing IAD. Considering the whole sample, these results show the presence of 53.85% of subjects with moderate Internet dependence and 1.19% with serious impairment: a prevalence rate lower than Italian epidemiological prevalence (about 5% of IAD).

Considering gender, IAT mean value in male students was 41.76 (DS = 9.82); a similar result was found in girls (mean IAT=41.90; SD=10.16). Considering gender in the OT group, the mean IAT were, for boys, 41.08 (SD=9.90) and for girls 42.57 (SD=9.48). On the other hand, in TT group, male average IAT value was 42.83 (DS=9.65), and mean IAT value was 41.67 (SD=10.40) for females. These results had no significant statistical difference with the Mann-Whitney test.

Regarding different types of schools, we found significant differences with the Mann-Whitney test in OT and TT (respectively of p <0.0001 and p <0.0001) considering the economic/commercial institute and the art/sports high school subgroups and correlating these with IAT values of these two groups.

In OT, the mean IAT of students from the economic/ commercial institute exceeded 3 points (44.31) the mean values of other institutes as well as students from the art/sports high school that exceeded the other institutes average IAT values of 3.58 points. On the other hand, in the TT sample, the students of economic/ commercial institute showed lower values, compared to the average IAT of the whole sample of 3.26 points (38.91; DS = 7.48) (Table 1).

| Type of School | Online Teaching Average Value (SD) |

Traditional Teaching Average Value (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 41.41 (9.80) | 42.17 (10.08) |

| Professional training | 40.96 (9.32) | 41.76 (10.73) |

| Technical training | 0 | 43.94 (10.90) |

| Artistic/Sports | 44.99 (9.76) | 40.65 (11.60) |

| Scientific/Mathematical/ Linguistic |

0 | 42.43 (9.41) |

| Economic/Commercial | 44.31 (11.56) | 38.91 (7.48) |

Considering an IAT score >40 and the amount of time on the web, the TT group exceeded the OT in every subgroup with a use of web between 4 and 7 hours a day, although no statistically significant difference was found. In the OT, the most represented amount of time on the web was between 1 to 3 hours/daily.

Considering gender, in the sample with IAT score >40, the network is used between 4 to 7 hours mostly in OT boys and TT girls; from 1 to 3 hours, in boys of both groups and, finally, in OT males and TT females for more than 7 hours. These differences, however, were not statistically significant. Regarding an IAT score <40, a significant use of the net is showed in OT males for the first range [1-3 hours], for the TT girls in the range from 4 to 7 hours and in boys of the two groups in the range [> 7 hours].

Comparing the genre and the main use of the Internet in IAT score >40 students, the main use of the network was music and video downloads, social network (like Facebook) and messaging (i.e Whatsapp). In particular, OT boys prefer to download from Internet; OT girls download, surf and text in equal measure; TT boys prefer messaging and TT girls surf on social networks.

Similar Internet uses in the student sample with IAT < 40 were underlined. Boys of both groups enjoy audio/music download and video files, while the girls of the same groups use messaging applications and social platforms.

In both of the subgroups, the most frequent Internet uses are represented by music and video downloads, social network platforms and application messaging. Specifically, in the OT sample, there are no differences considering IAT score: In fact, it turned out that the students of the professional institute and art/sports high school exploit Internet for downloading video and audio files and browsing on social networks, in similar ways. On the other hand, the economic/commercial institute students, with IAT cut-off < 40, mostly prefer messaging. Moreover, considering IAT cut-off > 40, students of the professional institute use the web to play online.

The same analysis was carried out in TT, in which differences were observed regarding IAT cut-off of 40. In fact, in the TT with IAT > 40, a greater use of messaging tool was found in the professional institute, art/sports high school and scientific/mathematical/linguistic high school; of social network platforms in the technical institute and of downloading programs in economic/commercial institute. Otherwise, in males of TT group with IAT <40, social navigation and file downloads were the most represented use of the web in professional institute and scientific/mathematical/linguistic high school, while in technical institute, messaging application use was more frequent.

After having dichotomized the whole sample into subgroups, depending on the IAT score (<40 or >=40), in order to determine the impairment due to the Internet, the comparison showed no differences between the two groups. The only significant difference between the two groups, OT and TT, was that OT students exceeded in socio-relational, personal life, and compensatory use (Fig. 2). However, considering each IAD subclasses average values in both OT and TT groups, they resulted to be exceeding or equal (“Compensatory use” and “Excitatory use” for OT) to the threshold values. These results demonstrated an average individual impairment in the whole sample.

4. DISCUSSION

With the digital development and the presence of Internet in our everyday life, social communication has changed and abandoned its original unidirectional conception of space-time. The space concept, in fact, is now perceived as independent and unencumbered by any physical frontier; meanwhile, the temporal sphere is metaphorically reduced: each of us could connect to the network whenever and wherever. The cultural exchange has favored knowledge and the changing of our usual learning system: we all could be users and producers of content and knowledge on the web. Although this change in habits has certainly brought several benefits in the social, cultural, and economic fields, it has also led to new problems and disorders. In fact, especially the younger generations tend to exceed in the use of the Internet, until it could cause a dependency, the Internet Addiction Disorder.

In this regard, this study wanted to evaluate, in the absence of such data in current literature, the association between the use of the Internet in teaching and a problematic use of the Internet itself. Doing so, we collected data from technologically oriented schools and compared it with the results from traditional teaching schools.

Our data shows that there is no significant difference in IAT rates between students of traditional and digital schools, with an IAT score > 70 in only 3 people in both kinds of the educational program (1.16% in the total sample), a result that is lower than national scores found in similar studies. In fact, a study on 275 Italian students, conducted by Pallanti and colleagues, indicated that the presence of IAD was 5.4%, a result that was also found similarly by another research group headed by Poli and Agrimi [23, 24]. This divergence can be justified by the fact that there’s a great variability of data caused by the administration of different tests and by their different cut-offs. Moreover, in Italian regions, there is a great variability in technological development. It should be noted that the national data in these studies was obtained with a diagnostic procedure that does not overlap with ours.

However, our results are in line with other international studies, where IAD prevalence was found to be between 1% and 9% [25, 26].

Although the prevalence of IAD was very low in our sample, almost 54% of students had an IAT score > 40, a result that is linked with a pathological use of Internet (PUI) and, therefore, with a higher risk of developing IAD. It’s important to notice that this data does not show gender differences.

Gender difference is an interesting topic in this field of research, with results that vary from study to study. Our data is aligned with other European studies: in Finland, for example, the prevalence of IAD is 4.5% in both genders [27]. However, a study conducted on almost 2000 students in Greece showed a higher prevalence of IAD in males [28], a data that has also been found in China (prevalence of 16% in male vs 11% in female sex) [29]. Our result could be linked to the fact that in Italy, Internet exposure is similar for both sexes, although in the group of students that scored > 40 at the IAT was possible to find difference in the usage of internet. In fact, OT boys use Internet mostly to download music or video, while OT girls use it to download, but also to chat with other people and to use social networks; TT boys use it to chat, and TT girls to navigate social networks. This different utilization, however, is not showed to be linked with gender difference, a result that could demonstrate that IA is not linked with how a person uses the Internet, but simply with the possibility to have access to it.

Another interesting finding in our study is that in both kind of educational programs, without distinction between different kinds of schools, only a minimum percentage of students uses the Internet to play games or for research information. This finding supports the hypothesis that adolescents in Italy use Internet to surf social networks and to chat with other people, especially using their smartphones. This result varies from other countries, like Japan, where online gaming is very popular between males and the access to Internet via PC is still very common [30].

Although our data demonstrates that there is no statistically significant association between online education and PUI, evaluating the percentage of students that scored > 40 at the IAT test (OT 53,30% vs TT 54,50%) suggests that the excessive use of Internet is linked to a massive waste of personal energy in terms of time and social life.

This is especially dangerous among adolescents, where self-identity is still not completely defined. As a result, IAD is linked to a higher risk of developing psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety and depression [30, 31]. In fact, it has been demonstrated that, although IAD is more frequent in people who have had an early exposure to the Internet, there are also some emotional risk factors, such as shyness, solitude, and the attitude to detach from personal problems [32–34], which are also traditionally linked to many psychiatric diseases. Moreover, it has also been demonstrated that there is a higher prevalence of IAD in patients affected by Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), where Internet is usually used as a solution to escape boredom [35].

To our knowledge, this is the first research that compares IAD scores between students from online teaching models and traditional teaching models. Our data suggests that, even if the usage of Internet for educational purpose is not linked to higher prevalence of IAD (1.20% in both OT and TT), the percentage of PUI is still alarming (53.83% in the total sample), hence it is important to prevent the onset of IAD by informing and monitoring both children and adults. On the other hand, this data suggest that OT may not be a risk factor for developing PUI than TT and that a consistent usage of Internet, as a learning tool, may be implemented in teaching practice.

However, several limitations to this study should be addressed in future researches. Firstly, we only assessed the prevalence of IAD in the sample at the time of first evaluation. Future researches could investigate the same topic on a longitudinal scale, in order to understand if the risk of developing IAD could be linked to the duration of the exposure to Internet usage. Moreover, it is difficult to confirm the motive of giving truth by the enrolled students, although they were instructed by their teachers before the administration of the assessment material. This could explain why our sample showed lower IAT total score than the national score found in similar studies in Italy.

Bias may also occur since the average value of TT in the technical training, scientific/ mathematical/ linguistic school is relatively higher than other TT schools and this observation may affect the results.

CONCLUSION

Future studies could, therefore, investigate the emotional mechanisms that can lead to an abnormal use of the Internet (i.e. to understand why children want to connect, how they structure their free time, how they interact with other people). It could also be fundamental to consider their relationships with parents, other family members, and teachers, investigating if parents are informed about how much time their children spend on the Internet and about the consequences that an abnormal use could lead to. In schools, it could be interesting to understand the knowledge and competence of teachers about the technology that can be used as educational instruments. In order to assess the presence of emotional, sleep, or academic performance impairment, future researches should include specific assessment tools or specific questionnaires, which were not included in our study. In fact, the interaction between internet use and its various impacts on the students would provide more insights in the comparison of different teaching types.

Another topic that could be worthy of future researches is the correlation between the use of Internet in schools and the teaching methods aimed at children with learning difficulties, such as ADHD, autism and dyslexia, a relationship that was already investigated in other studies but requires more data to be addressed properly [10, 36].

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT FOR PARTICIPATION

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

Not applicable.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All participants and parents, in case of underage students, provided written informed consent to permit submission and collection of the questionnaire for research purposes.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of this article is available at the Department of Mental Health of Luigi Sacco Hospital, ASST Fatebenefratelli Sacco, University of Milan, Milan, Italy.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirmed that the present paper had no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.