All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Effects of Personal Relationships on Physical and Mental Health among Young Adults- A Scoping Review

Abstract

Introduction:

This scoping review explores the association between young adults’ personal relationships and their physical and mental health. We reviewed studies that examined the nature and the quality of interaction in personal relationships and its effect on physical and mental health among young adults. We excluded studies conducted on the population with psychiatric conditions or who are differently abled.

Methods:

We used the following network databases to find relevant research: Google Scholar, SCOPUS, Web of Science, EBSCO, PubMed, ERIC, Science Direct and JSTOR from August 2021 to December 2021. We obtained 64 studies following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for scoping review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines.

Results and Discussion:

Thematic analysis of the selected studies indicates that personal relationships have the potency to either foster or hinder young adults’ physical and psychological functioning and well-being. Quality of relationships with family members such as parents, siblings, and extended family members are significantly associated with mental health and well-being Furthermore, studies showed that romantic relationship status and psychosocial characteristics within relationship contexts affect the mental health of young adults. In addition, our review showed that support from friendships, friendship features, and quality could support young adults’ self-esteem, mental health, and well-being. Although we find mixed results on personal relationships’ effect on physical health, few studies show that personal relationships affect cortisol levels, multiple areas of biological regulation, and women’s level of dysmenorrhea among young adults. The results justify the need to apply preventive intervention in the community to eliminate risk factors and enhance protective factors by imparting empirically validated knowledge, attitudes, and skills for relationships among young people. Investments in community-wide preventive interventions, interpersonal skill development agendas in counseling and psychotherapies, are recommended.

Conclusion:

The present review highlighted the underlying cultural influences on relationships and the necessity to promote relationship research in non-western cultures, given the underrepresentation of non-western cultures in research., we have highlighted the underlying cultural influences on relationships and the necessity to promote relationship research in non-western cultures, given the underrepresentation of non-western cultures in research.

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the last few decades, reconsideration of the adolescent-to-adult transition has given rise to a new conceptualization of the life stage known as emerging adulthood or young adulthood, which spans approximately 18-29 years [1]. The transition period from adolescents to adulthood happens when specific developmental changes occur, and relationship-building tasks become especially important. Although growth between the ages of 18 and 29 parallels preceding or succeeding periods, emerging adults, unlike teenagers, are neither school-going children nor minors under the law. They have attained physical and sexual maturity and are ready to start educational or occupational attainments [1]. In these late teens to mid-twenties journeys, young people often invest in higher education, begin working, form new relationships, and engage in other activities that prepare them for a healthy adult life [2]. At the same time, the young adulthood period shows heightened vulnerability to psychological issues, and many psychological disorders mark its onset [3].

According to Ryff & Singer, “interpersonal flourishing is a core feature of quality living” (p. 30) [4]. Young adults’ ability to have good social relationships is essential for their health, like success in education and employment [5]. Of all the factors that influence the psychological functioning of young adults, the quality of relationships and interaction they have with their family members, peers and partners are considered vital [6-8]. At the same time, many of the anger or stress-inducing factors arise in social contexts, as in troubled or dysfunctional interpersonal relationships [9, 10]. Kern et al.’s study of Seligman’s PERMA model stated that positive relationships are determinants of psychological well-being [11]. Results indicated that life satisfaction, gaining meaning, hope, and gratitude were significantly correlated with positive relationship perceptions—feeling connected to, supporting others, and being supported by others. Loss of interpersonal relationships or failure to establish close and supportive relationships contributes to clinical symptoms [7], like depression is both an outcome and precipitant of disruptions or loss of social relations. Many researchers have proposed that chronic relationship stress compromise mental and physical health [12-14].

1.1. Defining Personal Relationships

Interpersonal relationships refer to interaction among people in various contexts, including family or kinship relations, friendships, marriage, academic or workplace relations, neighborhoods, etc. It could be categorized into two major contexts: social and personal relationships. Social relationships involve a formal or informal relationship with neighbors, co-workers, customers, community members, and acquaintances. On the other hand, personal relationships mandate more intimacy, closeness, and interdependence than social relationships [15]. According to VanLear et al., relationships like couple relationships, (best)friends, and adoptive/foster families are voluntary personal relations, whereas parent-child, siblings, and grandparents are exogenously established personal relations [16]. Similarly, acquaintances and casual friends are voluntary social relations, and distant relatives and workplace relationships are exogenously established social relations. In this scoping review, we considered young adults’ personal relationships within the context of family, peer and romantic relationships.

1.2. Theoretical Perspectives on Personal Relationships

Sullivan’s interpersonal theory stressed the role of interpersonal relationships in developing personality and psychopathology. Sullivan described personality as “a relatively enduring pattern of recurrent interpersonal situations which characterize a human life” [17]. Sullivan observed that unstable interpersonal interactions could lead to the development of psychiatric disorders. For example, interpersonal problems be a significant factor in the onset and maintenance of eating disorders [18, 19]. Unq and colleagues argued that people with eating disorders generally had a friendly-non-assertive interpersonal style. Specific interpersonal problems are also associated with treatment outcomes [19].

Similarly, Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), developed by Klerman et al., focuses on improving a client's interpersonal relationships and social functioning to reduce distress [20]. IPT offers solutions to problems in four key areas: interpersonal deficits, or involvement in unfulfilling relationships; unresolved grief; difficult life transitions, such as retirement, divorce, or relocating; and interpersonal disputes, which arise from conflicting expectations between partners, family members, close friends, or co-workers. IPT focuses on changing relationship patterns rather than the accompanying depressive symptoms and addressing relationship issues that worsen these symptoms.

Attachment theory posits interdependent relations are both constructive and essential for human survival [21, 22]. Although Bowlby’s attachment theory describes infants’ attachment formation with the primary caregivers, these intimate interactions significantly contribute to an individual’s sense of security. Attachment security remains a powerful factor in adulthood too. It also forms the basis for the development of adult ‘internal working models’, which aid relational expectations, perceptions, and behaviors [23]. Adult attachment anxiety and avoidance are linked to interpersonal functioning as well as one’s health. Attachment insecurity is linked to one’s stress responses too—as it guides the appraising of stressful life events and, therefore, the physiological response to stress and recovery [24]. This, in turn, can cause depressive symptoms [23]. Anchoring on attachment theories, Feeney and Collins stated that well-functioning close relationships with family, friends and intimate partners are vital to thriving for humans, as they fulfill support functions [25].

Kiesler (1996) defined a transactional interpersonal model positing that individuals frame their interpersonal world and interactions [26]. Keisler’s interpersonal circumplex model presents interpersonal behaviors related to the agency (dominance- submissiveness) and affiliative interpersonal behaviors (friendliness-disengagement). It was found that depressed individuals exhibit interpersonal behaviors in a disengaged manner and lack self-esteem and interpersonal agency [23]. Psychopathology and distress are the results of delimited, repetitive, maladaptive transactional cycles that were established to protect the sense of self but invariably led to self-defeating, restricting patterns of relatedness [26].

Bowen’s family systems theory considers the family as an emotional system. He stated that the driving forces underlying all human behavior are created due to the striving of family members for balance between togetherness and distance [27]. The primary aim of Bowenian therapy is to reduce emotional crisis or anxiety generated within the family system by facilitating awareness about emotional system functions and differentiation among family members [28]. Eight interlocking principles in Bowen’s theory explain the differentiation of self, triangulation, nuclear family emotional system, family projection process, emotional cut-off, multigenerational transmission process, sibling position and societal regression [27, 28].

1.3. Importance of Personal Relations

Research findings emphasize that relationships are important to people, and domains like family, friendships, and romantic relationships are considered significant-close relationships in one’s life [29]. Successful relationships with family, friends, colleagues, and peers are essential to maintaining one’s well-being [30] and physical and mental health [14]. Harmonious relationships are positively related to one’s psychological well-being [31]. However, rejections and negative interactions lead to poorer well-being. For example, Ford and Collins reported that rejection had a lasting impact on well-being among young adults [32]. These authors found a significant increase in perceived stress and depressed mood as well as significant impairments in self-regulatory capacity on days the participants felt rejected. Besides, it was found that rejection’s effects on sad mood and self-regulatory ability lasted until the next day.

In a study exploring the most important contributor to the meaning of life among young adults, Lambert et al. found that sixty-eight percent of the young adults reported that their families in general or a specific family member (e.g., sister, parent) were the essential contributors to the meaning of life [33] followed by friends. Chow and Ruhl examined everyday stressors among young adults [34]. They found that 46–82 percent of everyday stressors for emerging adults are related to interpersonal interactions, particularly conflicts with friends and romantic partners. Siu & Shek also identified the stressful social situations for Chinese young adults [30]. These authors reported that it was easier for young adults to develop and maintain a friendship, and perceived self-efficacy was greater in dealing with peers. However, young adults were least confident in handling conflicts with family members, colleagues and supervisors, and expressing love to the one admiring. The other situations with relatively lower self-efficacy were balancing time for friends, family, partners, study, work, and showing care to family members.

Darling et al. examined stress in college students’ relationships—friendships, romantic relationships, and family relationships [35]. Significant themes emerged in their research in friendship and love domains are: leaving friends, living with friends, reconsidering friendship relationships, managing unhealthy love relationships, ending relationships, or missing a relationship. Themes on parent relationships included independence from parents, managing parental plans and prospects, parental marital issues, family communication, health, and relationships. Though inadequate, this limited research indicates that young people face difficulties maintaining healthy personal relationships. In the current scoping review, we present and synthesize research findings on various personal relationship networks [36] of young adults, i.e., family— parents, siblings and extended family— romantic partners, and peers and discuss how it poses important implications for young adults’ mental & physical health and well-being.

1.4. Goal of the Review

By scouring the literature, we aimed to understand the risk and protective factors within personal relationships that influence young adults' physical and mental health and well-being. The review's precise questions were: What factors in personal relationships can harm or help young adults' health and well-being, and how does it impact?

2. METHODS

A scoping review of the literature was used in this research. The scoping review provides a comprehensive picture of the field that can be utilized to (a) disclose the key concepts that underpin the study field, (b) clarify the working definition, and (c) define the conceptual border of a topic [37]. Given that the study matched all three criteria, a scoping review was deemed the best strategy for achieving the research objectives. We followed The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analysis extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines [38, 39].

2.1. Search Strategy

The following databases were combed: Google Scholar, SCOPUS, Web of Science, Taylor and Francis Online, EBSCO, PubMed, ERIC, ScienceDirect and JSTOR. Online. Searches were performed using the following keywords: young adults/ youth, college students, interpersonal relationships/ personal relationships/ social relationships, close relationships, family, sibling relationships, extended family, romantic relationships, peers, friendships, mental health, physical health, health, well-being, life satisfaction and happiness. The Boolean operators “and” and/or “or” were used to combine the terms in the search. To find more relevant articles, we looked at “related articles”, “related research”, “cited by,” and “Recommendations” under the search results. References of obtained articles were checked, and articles that were found relevant were hand searched. The two independent reviewers searched for the studies from August 2021 to December 2021. A third reviewer evaluated the selected studies. The reviewers discussed and finalized the inclusion or exclusion of the studies.

2.1.1. Inclusion Criteria

We used the following criteria for the selection of the articles:

(1) Written in English.

(2) Published article or unpublished dissertation.

(3) Published between 1990 to 2022.

(4) Samples were either exclusively young adults/ have included the young adulthood phase.

(5) Samples should be healthy young adults.

(6 Studies linking personal relationships with health, well-being, life satisfaction and happiness.

2.1.2. Exclusion Criteria

- Studies with samples having psychiatric conditions and disadvantaged populations (e.g., Handicapped, having any significant physical health conditions like arthritis, cancer, parents having a mental illness, etc.) were not considered as those factors may act as covariates.

We adopted the following six quality criteria from scoping review articles recently published by Rubega et al. [40] and Bertuccelli et al. [41]:

- Study objectives are clearly stated

- Description of inclusion and/or exclusion criteria

- Data collection and processing are clearly described and are reliable (whenever applicable)

- Outcomes are topic relevant

- Appropriate statistical analysis techniques

- Presentation of the result is sufficient

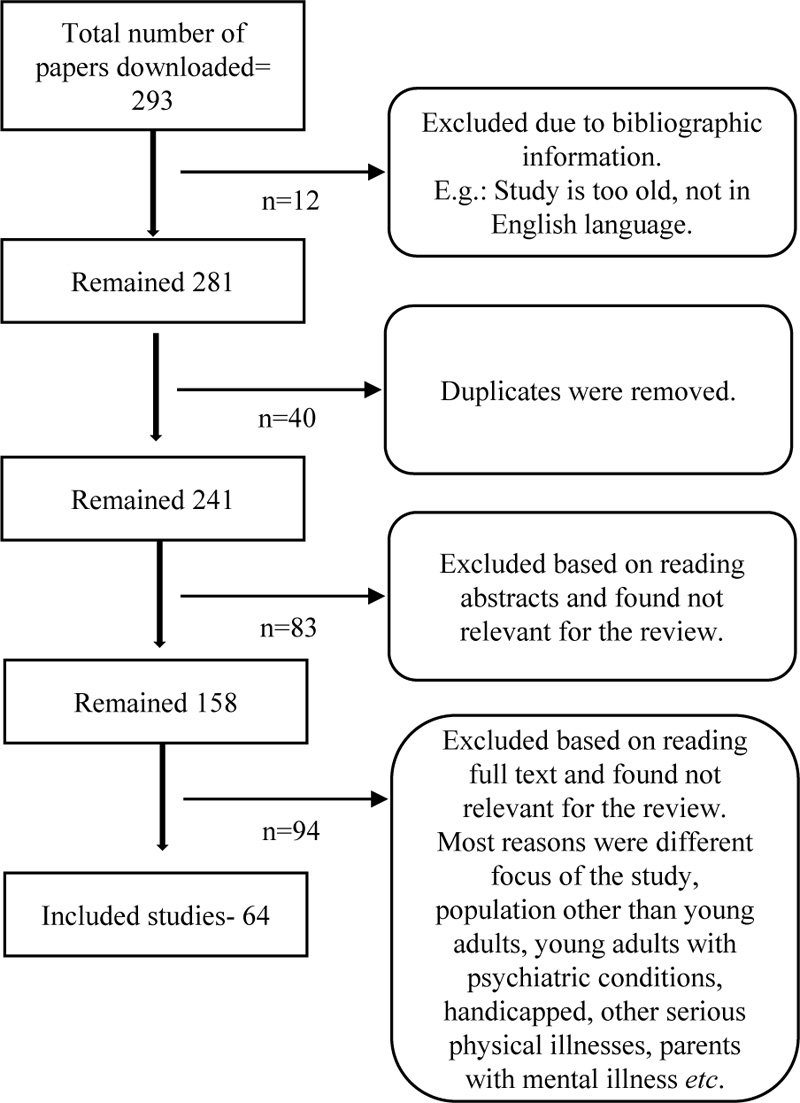

We found 64 articles that fulfilled the above criteria and were included in this review. The geographical distribution of these studies is presented in Table 1. Fig. (1) presents a PRISMA flow chart for the selection of articles.

| Location of studies | Frequency |

|---|---|

| USA | 48 |

| Canada | 4 |

| Italy | 2 |

| Netherlands | 2 |

| UK, Australia, Germany, Spain, Sweden, Poland, China, and Taiwan. | 8 |

2.2. Data Analysis

We used thematic analysis to synthesize and organize the findings of the selected studies. We carefully read, summarized, and synthesized the available information into different categories/themes. We categorized the entire review into different sections — considering family relationships, romantic relationships, and peer relationships as major personal networks [36] of young adults.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Based on the keywords used for the search and the inclusion and exclusion criteria prescribed for the review, we identified 64 studies linking personal relationships to physical and mental health. Of them, 54 studies examined the association between personal relationships and mental health, and ten studi es explored the association between personal relationships and physical health. We conducted a thematic analysis of the 54 studies examining the link between personal relationships and mental health and explored the themes and sub-themes based on the nature and type of the relationship examined. We found that the studies could be grouped under three major contexts of relationship— relationships within the family, romantic and sexual partners and peers. We also found sub-themes under these major contexts. The major themes and sub-themes are presented Figs. (2, 3, and 4) for family, romantic and sexual partner, and peer relationships, respectively. We did not conduct any thematic analysis for studies linking personal relationships and physical health, as there were only ten studies.

3.1. Family Relationships among Young Adults

Family relationships play a critical part in determining an individual’s well-being, for better or worse, throughout their lives [42]. Lambert et al. [33] findings point out that family relationships are prominent and pervasive in providing meaning to young adults. Closeness to the family is a strong predictor of meaning in life, even when personal variables self-esteem, autonomy, competence, and closeness to friends influencing the meaning of life were controlled [33]. Correspondingly, youth who established positive relationships with their family have improved well-being than those who do not [43]. Table 2 presents an overview of the nature and details of the studies on family relationships.

| Title & Year | Country | Research Design | Sample | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relations of Internalizing Symptoms to Conflict and Interpersonal Problem-Solving in Close Relationships [8] (2005) | USA | Quantitative, Cross-sectional | 123 college students | • Interpersonal conflict in close relationships • Interpersonal problem solving • Depressive symptoms • Anxiety symptoms. |

| Family as a salient source of meaning in young adulthood [33] (2010) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional | Undergraduate students | Meaning in life. |

| “Family Comes First!” “Relationships with family and friends in Italian emerging adults.” [44] (2014) |

Italy | Mixed method. Study1: Qualitative study use focus group or interview. Study 2: Quantitative, self-report questionnaire. |

Study 1: 39 emerging adults Study 2: 474 participants |

Study1: emerging adults' perception of interactions with both family and friends. Study2: how family and friends' importance to identity linked to life satisfaction |

| Extended Family Relationships: How They Impact the Mental Health of Young Adults [45] (2017) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional, | 304 undergraduate students | • Quality and quantity of extended family relationship • Perceived social support – family of origin • Perceived social support – extended family • Self-esteem • Depressive symptoms |

| Close Relationships and Happiness Among Emerging Adults [6] (2010) | USA | Quantitative Cross-sectional |

314 young adults | • Relationship Quality and Conflict • Happiness • |

| The roles of parental attachment and sibling relationships on life satisfaction in emerging adults [46] (2019) | Italy | Quantitative Cross-sectional |

253 emerging adults aged 20–31 | • Quality of parental attachment • Quality of sibling relationships • Level of life satisfaction |

| Positive Parenting Improves Multiple Aspects of Health and Well-Being in Young Adulthood (2019) [47] |

USA | Longitudinal cohort, quantitative. | N= 15000+, Baseline age, in years (range: 12-22 | • Offspring satisfaction with the parent-child relationship • Parenting styles • Family dinner frequency. • Psychological well-being • Physical health • Mental health • Health behavioral outcomes |

| The Role of Parents in Emerging Adults’ Psychological Well-Being: A Person-Oriented Approach [43] (2019) | Spain | Quantitative Cross-sectional |

1502 undergraduate students | • Parenting dimensions • Family control • Psychological well-being • Psychological distress |

| Loneliness in young adulthood: Its intersecting forms and its association with psychological well-being and family characteristics in Northern Taiwan. [48] (2019) | Taiwan | Cross-sectional, quantitative | Two thousand seven hundred forty-eight young people, a cohort sample from the Taiwan Youth Project (TYP). | • Loneliness • Psychological well-being • Family characteristics |

| Depression and perception of family cohesion levels and social support from friends in emerging adulthood at a university mental health clinic [49] (2020) | USA | Quantitative cross-sectional. | Three hundred seventy-two emerging adult individuals who were availing of individual or family therapy services from the couples and family therapy training clinic housed within the department of family science at the university of Maryland. | • Familial cohesion • Social support from friends • Depressive symptoms |

| The association between current maternal psychological control, anxiety symptoms, and emotional regulatory processes in emerging adults [50] (2020) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional |

N = 125 Emerging adults, undergraduate students from the state university in southern California. |

• Maternal psychological control • Anxiety symptoms • Emotion regulation • Social Stress |

| Sibling relationships and best friendships in young adulthood: Warmth, conflict, and well-being (2006) [31] | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional | 102 undergraduates | • Self-esteem • Loneliness • Relationship quality |

| Family Structure and Psychological Health in Young Adults [51] | UK | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 708 undergraduate students aged between 18 - 21 years | • The Locus of Control of Behaviour • dispositional optimism • factors of family environment • psychological distress |

| Extended Family Relationships: How They Impact the Mental Health of Young Adults [45] (2017) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional | 304 undergraduate students (between 18 and 21 years of age) | • Quality and quantity of extended family relationships • Perceived social support – family of origin • Perceived social support – extended family • Self-esteem • Depressive symptoms |

3.1.1. Relationship with Parents

The transition to the young adulthood stage brings positive and negative changes within child-parent relationships. Undesirable happenings like regular family conflict might disrupt emerging adults’ maturation, autonomy, and emotional and social health [52]. Demir examined the role of relationships between father and mother and the association with happiness [6]. Mother-child relationship quality emerged as a substantial predictor of happiness than father-child relationship quality, irrespective of young adult's relationship status —single or committed. Ponti & Smorti found that relationships with the mother and father were, directly and indirectly, related to life satisfaction and well-being [46]. The path analysis showed that the level of secure attachment to both parents was closely and favorably connected with perceptions of emerging adults’ overall life satisfaction. However, attachment to the mother is a somewhat higher predictor than the father. As in Demir’s [6] study, Londahl et al.’s [8] study also stressed the importance of young adults’ relationships with their mothers. Conflict with the mother was correlated with depressive symptoms [8]. Miller and Lane [53] found that college students were closer to their mothers than their fathers in terms of spending more time, getting more egalitarian treatment, closeness, and positive experiences which partially explains that young adults display more distress when experiencing conflicts with their mother than father [6, 8].

Chen et al.'s study on positive parenting and young adults’ well-being reported that relationship satisfaction was linked to improved emotional well-being, a lower risk of mental illness, eating disorders, being overweight/obese, and use of marijuana [47]. Perceived parental control is positively associated with anxiety [50]. Young adults who are more psychologically and behaviorally regulated by their parents experience greater psychological distress and lesser psychological well-being. Greater parental authoritativeness and regular family dinners were linked to higher emotional well-being, less depressive symptoms, reduced risk of overeating, and certain sexual behaviors among young adults [47]. Late adolescence and young adulthood is a period where they start being more autonomous. Individuating from parents and gaining autonomy, and being able to make responsible decisions for oneself are significant developmental needs during late adolescence [54]. Many theorists define the process of individuating and gaining autonomy as a task that must be accomplished to progress from adolescence to adulthood [55]. Therefore, when parents exert greater parental authority, too much emotional support and psychological control might hinder young adults’ developmental needs and adversely affect their mental health and development. Changing the parent-child dynamics and redefining the relationship dynamics between parents and young adult children would make positive changes. Relinquishing over-control, encouraging responsibility and redefining relationships as adult-adult would be favorable [55].

García-Mendoza et al. reported that participants with better family relationships —high levels of parental involvement, parental support for autonomy, parental warmth, and low levels of behavioral and psychological control— were shown to be more psychologically adjusted [43]. In addition, they found that when parental support is too low, young adults achieving emotional autonomy lead to psychological distress and lowered well-being [56]. Positive relationships with father and mother were linked to fewer depression symptoms across different age groups [57]. Roc reported that perception of family cohesion is negatively correlated with their depressive symptom levels [49]. Relationships with parents are strongly linked to emerging adults’ well-being and distress [43].

Perceived social support from the family of origin is also a significant contributor to depressive symptoms and self-esteem levels for men and women [45]. Wagner et al.’s review of family characteristics that lead to youth suicidal behaviors reported—suicidal behaviors, both fatal and nonfatal, have been consistently connected to strained parent-child interactions like high conflict and low closeness [58]. Insecure parent-child relationships and family system issues such as cohesion and adaptability are consistently linked to nonfatal suicidal symptoms than complete suicides [58]. However, low parent-child affection has fewer negative psychological consequences for young adults when they are into some employment and marital and parental identities to a lesser extent [59]. Together these studies show that relationship quality and conflicts with parents impact young adults’ happiness, mental health, and well-being and have highlighted the importance of young adults having close, affectionate relationships with their parents. We also infer that healthy parental involvement and support and experience of cohesion and feelings of closeness with parents facilitate mental health. On the other hand, over-involvement and control displayed by parents affect the mental health of young adults adversely.

3.1.2. Relationship with Siblings

Studies on sibling relationships are relatively sparse compared to other family relationships, although it is often a lasting family relationship across all cultural contexts. High-quality sibling relationships characterized by positive features like closeness have been found to be linked to well-being. At the same time, sibling relationships characterized by conflicts were linked to poorer well-being, increased chances of depression, and drug use in adulthood [42]. Positive sibling relationships, defined by warmth, affection, and emotional and instrumental support, are associated with an individual’s well-being. On the other hand, conflicted sibling relationships are associated with unfavorable psychological adjustment, such as internalizing and externalizing behaviors [46]. Sherman et al. reported similar findings that young adults with harmonious sibling relations—high warmth, low conflict— had higher well-being, and those with affect-intense —high warmth, high conflict— sibling relationships had low well-being [31]. On the other hand, Ponti & Smorti's research did not find any evidence for sibling conflict negatively affecting emerging adults’ life satisfaction [46].

Some gender-specific traits and characteristics in relationship context might influence relationship dynamics and satisfaction. Some study results pointed that the gender structure of siblings affects mental health. Cassidy et al. reported that those having a brother experienced the most psychological distress [51]. The most psychologically distressed were boys who have brothers; the second most distressed were girls with brothers, closely followed by both boys and girls with both brothers and sisters. The participants who experienced the least psychological distress were the boys and girls having sisters. Based on the literature, they reasoned that the male siblings caused increased conflict and decreased cohesion within the sibling relationship. Given that sibling solidarity is regarded as a significant source of social support during family conflicts, it stands to reason that female siblings may provide greater support than male siblings – resulting in possessing male siblings causing increased psychological distress and female siblings lowering the distress.

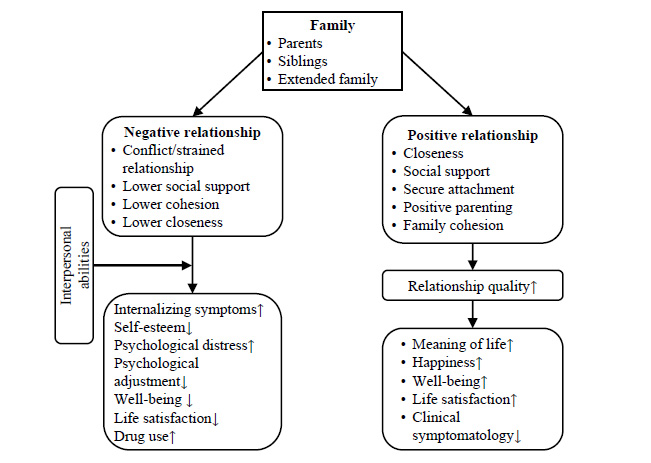

3.1.3. Relationship with Extended Family Members

They are an element of family structure that is often overlooked as having implications for well-being. Extended family members include other non-parental members, including grandparents and other relatives. Evidence shows an association between extended family relationships and mental health among young adults. Though perceived social support from the family of origin is the strongest predictor of self-esteem and depression in young adults, perceived support from extended family members is also moderately connected [45]. These results suggest that extended family support works in tandem with assistance from the family of origin to improve self-esteem and depression. Females benefit from positive extended family relationships positively impacting their mental health, whereas males get negatively affected by increased closeness of extended family relationships, with depressive symptoms elevated by closer extended family relationships [45]. These studies conclude that the connection between extended families and youth well-being is not as simple as we assume. People may gain from extended family ties or experience negative mental health implications depending on the quality of interactions [60]. A conceptual diagram indicating family relationship factors affecting young adults’ mental health is presented in Fig. (2).

Overall, studies examining the association between family relationships and mental health outcomes among young adults indicate that individuals experience both positive and negative mental health outcomes within one’s own family relationships. Closeness among family members, social support, secure attachment, positive parenting from parents, and good family cohesion was found to be positive factors that enhance mental health. Feeney and Collins argued that social support acts as a buffer during stress and is an interpersonal process that promotes positive well-being. As portrayed in Fig. (2), social support is a positive relationship feature, increasing young adults’ relationship quality with their families. This, in turn, acts as a promoter of well-being and mental health and lowers the clinical symptomatology. Similarly, secure parental attachment, closeness, and family cohesion also seem important in maintaining good relationships. Even though sibling relationships and extended family members also predict well-being, relationships with parents seem more crucial and predictive of mental health and well-being. At the same time, conflicts in family relationships, poorer family cohesion, and social support can contribute to internalizing symptoms, psychological distress, drug use, reduced self-esteem, life satisfaction, adjustment, and well-being.

3.2. Romantic Relationships among Young Adults

Current section deals with young adults’ romantic relationships and their effects on their mental health and well-being. Getting into romantic relationships and experiencing intimacy are considered critical developmental tasks accompanying the transition to adulthood [39]. The social convoy model [40] argues that people organize their close relationships hierarchically, and young adulthood is a key time for formal and casual romantic relationships to develop [5], and they may prioritize it more. Romantic experiences starting during adolescence and delayed marriage allow premarital relationships for young adults [41].

Adolescents’ relatively short and casual romantic relationship patterns progress to more serious, committed relationships in young adulthood [42, 43]. Romantic experiences in this period have developmental significance for well-being — prolonged singles reporting decreased life satisfaction and increased loneliness [44] and romantic competence associated with decreased internalizing symptoms like anxiety and depression [45]. Depression trajectories associated with adolescent dating gradually fade away when they enter the young adulthood period; decreased symptom trajectories were related to young adult unions and the combination of adolescent dating with young adult singlehood [46]. Meeus et al. reported that when young adults transition to intimate relationships, they psychologically enter into more meaningful relationships [47]. When people reach early adulthood, the psychological significance of their intimate partner relationship becomes more apparent— the relationship quality gets further stable and is linked to their emotional adjustment [47]. Table 3 presents an overview of the nature and details of the studies on romantic relationships.

| Title & Year | Country | Research Design | Sample | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predicting dysphoria and relationship adjustment: Gender differences in their longitudinal relationship. Sex Roles(2001) [61] | USA | Short-term longitudinal, quantitative | 145 dating college students | Depression Relationship satisfaction of couples |

| Relationships with intimate partner, best friend, and parents in adolescence and early adulthood: A study of the saliency of the intimate partnership [62](2007) | Netherlands | six-year longitudinal study quantitative |

1041 adolescents and early adults, aged 12–23 | Parental support Relational commitment to best friend and intimate partner Emotional problems Relationship status |

| Together is better? Effects of relationship status and resources on young adults’ well-being [63](2008) | Netherlands | six-year longitudinal study quantitative |

N=1775, between 18 and 30 years of age | Well-being Relationship status Material resources Personal resources Social resources |

| Perceived social network support and well-being in same-sex versus mixed-sex romantic relationships [64](2008) | Canada | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | N=458 young adults | Perceived support for the relationship Relationship well-being Mental health. Physical health. Other support |

| Profiles and Correlates of Relational Aggression in Young Adults’ Romantic Relationships. [65](2008) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 479 young adults | Relational Aggression and Relational Victimization Social-cognitive Factors Normative Beliefs Retaliation Beliefs Relationship Characteristic Factors Trait/dispositional Factors Mental Health Factors |

| Depressive Symptoms in Young Adults: The Role of Attachment Orientations and Romantic Relationship Conflict (2009) [66] | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 110 undergraduate students between 18-25 years | Attachment orientations Conflict behavior Depressive symptoms |

| Casual Sex and Psychological Health Among Young Adults: Is Having ‘Friends with Benefits’ Emotionally Damaging? Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health”(2009) [67] | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 1,311 young adults | Partner type Psychological well-being |

| “Romantic relationships and the physical and mental health of college students”(2010) [68] | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 1621 college students | Relationship status Health problems Over weight Risky behavior Substance use |

| “Non-marital Romantic Relationships and Mental Health in Early Adulthood: Does the association differ for women and men?”(2010) [69] | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 1611 young adults | Depressive symptoms Substance abuse Relationship status Quality of relationship |

| “Romantic Relationship Status Changes and Substance Use Among 18- to 20-Year-Olds”(2010) [70] | USA | Longitudinal, quantitative. | a community sample of 939 individuals | Substance use Relationship status Depressive symptoms |

| Breaking up is hard to do: The impact of unmarried relationship dissolution on mental health and life satisfaction(2011) [71] | USA | Longitudinal, quantitative | 18 to 35-year olds (N = 1295) | Psychological distress Life satisfaction Relationship and Break-up Characteristics |

| Romantic Relationships, Relationship Styles, Coping Strategies, and Psychological Distress among Chinese and Australian Young Adults [72] (2011) | Australia, China | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 144 Anglo-Australian and 250 Hong Kong Chinese undergraduate students | Relationship style Coping strategies Psychological distress |

| Caught in a bad romance: Perfectionism, conflict, and depression in romantic relationships [73] (2012) | Canada | Longitudinal, quantitative | 226 heterosexual romantic dyads | Perfectionistic concerns. Conflict Depressive symptoms Other-oriented perfectionism Neuroticism. |

| Attachment Anxiety, Conflict Behaviors, and Depressive Symptoms in Emerging Adults’ Romantic Relationships [74] (2012) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 45 dyadic couples ages 18–25 years | attachment anxiety in intimate relationships Conflict Behaviors depressive symptoms |

| Examination of Identity and Romantic Relationship Intimacy Associations with Well-Being in Emerging Adulthood Identity [75] (2012) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 437 emerging adults | relationship type Identity Measure Intimacy Measures Well-Being |

| Committed Dating Relationships and Mental Health Among College Students [76] (2013) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | Eight hundred eighty-nine undergraduate students aged 18 to 25. | relationship status Depressive symptoms Alcohol use. |

| Romantic Relationships and Health among African American Young Adults [77] (2013) | USA | Longitudinal, quantitative | 634 African American respondents transitioning to adulthood | Mental health Physical health Relationship commitment Relationship satisfaction Partner warmth Partner hostility Partner antisociality |

| Friendship and Romantic Stressors and Depression in Emerging Adulthood: Mediating and Moderating Roles of Attachment Representations [34] (2014) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 164 emerging adults age ranging from 18 to 21 years | Friendship and Romantic Stressors Attachment Representations depressive symptoms |

| Perceived Social Support and Mental Health Among Single vs. Partnered Polish Young Adults [78] (2015) | Poland | Quantitative, cross-sectional | 553 young adults aged 20–30 | General Health Mental Health Perceived Social Support current relationship status |

| Romantic competence, healthy relationship functioning, and well-being in emerging adults [79] (2017) | USA | Mixed method of qualitative and quantitative, cross-sectional Includes multiple studies. |

Emerging adults between 18 - 25 years. | Romantic competence relational and individual well-being |

| Binge Drinking and Depression: The Influence of Romantic Partners in Young Adulthood [80] (2017) | USA | Quantitative, longitudinal. | 1,111 couples at least 18 years of age | Binge Drinking Depression |

| How Much Does Love Really Hurt? A Meta-Analysis of the Association Between Romantic Relationship Quality, Breakups and Mental Health Outcomes in Adolescents and Young Adults [81] (2017) | USA | Meta-analysis | 20 manuscripts U.S. and non-U.S. adolescents (13–17 years old) and young adults (18–29 years old). |

Romantic relationship quality Romantic Relationship Breakups Mental health outcomes |

| Abilities in Romantic Relationships and Well-Being Among Emerging Adults [82] (2017) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional | 145 emerging-adult undergraduate students e aged 18 to 25 | Relational anxiety Attachment anxiety and avoidance Self-efficacy in romantic relationships Well-being |

| Sexting within young adults’ dating and romantic relationships [83] (2020) | Review | - | Sexting research among young adults. | |

| Patterns of Romantic Relationship Experiences and Psychosocial Adjustment from Adolescence to Young Adulthood [84] (2021) | Germany | Quantitative, longitudinal. | N=2457 adolescents and young adults (age 16 until 25) | Romantic involvement history Depressive symptoms Loneliness Self-esteem Life satisfation |

| Romantic Relationship Quality and Suicidal Ideation in Young Adulthood [85] (2021) | USA | Quantitative, longitudinal. | 132 adolescents followed through young adulthood | Suicidal Ideation Relationship Status Relationship Quality. |

| Substance use behaviors in the daily lives of U.S. college students reporting recent use: The varying roles of romantic relationships [86] (2021) | USA | Ecological Momentary Assessment, quantitative | young adults aged 18–21 | Relationship status Relationship quality Substance use Childhood family adversity |

3.2.1. Relationship Status

According to Braithwaite et al. [68], college students in committed romantic partnerships report higher well-being than single college students. Individuals who were in committed relationships had fewer mental health issues. Being in a committed love relationship reduces problematic outcomes primarily by reducing the number of sexual partners, which reduces risky behaviors and adverse outcomes. College students in committed dating relationships were less likely than their single peers to participate in risky behaviors (e.g., binge drinking, driving while drunk). The incidence of less risky behaviors in committed relationships mediated the link between relationship status and health issues. Whitton et al. investigated similar variables and reported that being in a committed relationship was related to reduced depressive symptoms compared to being single for college women but not for males [76]. Being involved in a committed relationship was linked to reduced problematic alcohol use for both genders. Soons & Liefbroer studied romantic relationships to happiness and concluded that singles have the lowest level of happiness, followed by young people in committed relationships and cohabitators [63]. Adamczyk & Segrin investigated whether young individuals in non-marital romantic relationships have better mental health and fewer mental health problems than singles [78]. According to their findings, singles reported lower emotional well-being than coupled individuals. There were no differences between single and paired individuals in social and psychological well-being, somatic symptoms, anxiety, sleeplessness, social dysfunction, and severe depression. Simon & Barrett [69] also found that current romantic involvements are related to the emotional well-being of young adults and associated with fewer depressive symptoms, in line with most of the research concerning relationship status and mental health. Although studies show prolonged singlehood as a risk factor, its nature and impact might vary culturally. In western cultures, young people may feel stressed and lonely and out of step with peers if they are not in a romantic relationship. They might also have pressure to conform to peer norms. However, in non-Western and collectivistic cultures such as India, parents exert more constraints and control on children, due to which young people experience pressure and stress in keeping their relationships private [87, 88]. Therefore the experience of Indian young adults can be different. Future studies might examine such cultural differences more elaborately.

There are four forms of romantic partnerships among rising adult college students: casual daters (23%), committers (38%), settlers (30%), and volatile daters (8%) [89]. Eisenberg et al. showed that casual partner/ friends with benefits/ hook-ups were not psychologically harmful [67]. Young people who were sexually active and engaged in sexual intercourse with someone they were not dating appear not to be at any greater risk than sexually active young individuals in committed partnerships. However, having a devoted partner and being sexually active were related to greater mental health among women. Conversely, Barr et al. [77] reported that being in a romantic relationship does not affect either depression or physical health. However, it is important to note that people in high-quality relationships regularly outperformed single or low-quality relationships in terms of mental health outcomes. In no case was long-term, high-quality relationships more positively connected to health than the recent shift to a high-quality relationship. On the other hand, a persistent low-quality relationship was consistently more negatively connected to health, particularly alcoholism, than a recent move to a low-quality relationship. In their investigations, the pathways linking relationship quality to health do not appear to be gendered.

3.2.2. Individual Factors

Individual characteristics like attachment and self-efficacy within the context of romantic relationships are found significant for partners’ well-being. Young adults’ characteristics like attachment anxiety and conflicting behaviors in romantic relationships also contribute to depressive symptoms [74]. Similarly, individual characteristics like lower attachment anxiety and social distress in group dating situations and greater self-efficacy in romantic relationships predicted happiness and low psychological distress [82]. Hazer and shaver’s theory explains the association of attachment styles to their romantic relationship experiences [90]. They explained three attachment styles secure, avoidant, and anxious-ambivalent and stressed that individuals with these three styles experience their romantic relationships differently. Individuals with secure attachment styles have happy romantic experiences, endure longer, and are less likely to get divorced than avoidant and anxious-ambivalent individuals. Avoidant and Anxious-ambivalent individuals may experience jealousy, obsession, emotional highs and lows, and fear of intimacy [91, 92]. Furthermore, Attachment Diathesis-Stress Process Model [93] states that when a person is under external stress, attachment insecurity can generate maladaptive perceptions and behaviors. These maladaptive tendencies could adversely affect an individual's personal and relational well-being.

3.2.3. Relational Factors

Psychosocial variables like relationship styles and coping strategies have more significance than demographic factors (e.g., age) in influencing mental health outcomes [72]. A correlational examination of women’s romantic relationship intimacy reports found significant relationships between intimacy and well-being indicators in Johnson et al.’s study [75]. Positive intimacy is associated negatively with social avoidance, while intimacy frequency and intensity are associated negatively with loneliness. Apart from the above findings common for both genders, sexual intimacy was negatively correlated with social avoidance for men alone. Blair & Holmberg showed that perceived social network support for romantic relationships predicts higher relationship well-being and more positive mental and physical health outcomes for relationship partners [64]. Furthermore, perceived social support was substantially related to relationship well-being, accounting for 57% of the variance. Relational well-being has a moderate association with mental health and a weak connection with physical health, accounting for 15% and 3% of the variance in these dimensions, respectively. Simon & Barrett analyzed relational quality based on partner support and strain [69]. Partner support is connected with reduced depression, whereas partner strain is associated with more depression for both genders. Partner support is linked to fewer substance issues, whereas partner strain is associated to increased substance issues. The link between these aspects of a current relationship and substance abuse is more robust in males than women [69].

Gallaty & Zimmer-Gembeck [94] reported that daily romantic problems and positive relationship events were related to same-day mood ratings in 17-22-year-olds. This implies that relationship functioning is related to young adults’ emotional well-being; however, average weekly levels of positive and negative relationship events were not correlated with levels of depressive symptoms. At the same time, several additional researchers investigated the relationship between romantic relationship quality and clinical symptomatology. Remen & Chambless [61] reported a link between self-reported relationship satisfaction and depressive symptoms. Similarly, Whitton & Kuryluk [95] explored associations between romantic relationship satisfaction and depressive symptoms in emerging adults in non-marital dating relationships. They reported a negative correlation between relationship satisfaction and depressive symptoms for men (small effect) and women (medium to large effect). Relationship satisfaction accounted for 14% variance in depressive symptoms of women, being closely similar to that of 18% observed for married women [96]. Linking romantic relationships with suicidal ideation, Still [85] found that respondents who report higher levels of romantic relationship quality in any romantic relationship type are less likely to report suicidal ideation.

3.2.4. Relational Aggression

Chow & Ruhl’s [34] study findings showed that emerging adults who face higher romantic stressors had increased chances of feeling anxious and uncertain about their attachment ties, which leads to increased depressive symptoms. Marchand-Reilly [66] reported adopting more aggressive behaviors in romantic relationships had higher depressive symptoms. Mackinnon et al. [73] indicated that, even when baseline depressive symptoms were adjusted for, dyadic conflict mediated the link between perfectionistic concerns and depressive symptoms. Further, depressive symptoms acted as both an antecedent and an outcome of the dyadic conflict. In romantic partnerships, some degree of involvement in relational aggression was rather prevalent [65]. Goldstein et al. [65] studied correlations between aggression profile and mental health parameters in the context of young adults’ romantic relationships. The results demonstrated that the aggressiveness profile was linked to depression and anxiety symptoms. In terms of anxiety and depression, low aggressors/low victims reported much fewer symptoms than any other profiles. In terms of depression, low aggressors/low victims reported significantly fewer symptoms than high aggressors/low victims or high aggressors/high victims. Studies show that relational aggression negatively affects the well-being of romantic partners and that insecure attachment is predictive of relational aggression [97].

3.2.5. Romantic Relationship Circumstances and Risk Behaviours

Several studies have tested romantic relationship associations with risky behaviors. Ouytsel et al. [83] conducted a review of sexting in young adults’ dating and romantic relationships and concluded that connections between sexting and adverse mental health outcomes such as anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation are most common for those who engage in sexting under pressure or receive unwanted sexual photos. In Barr et al.’ s [77] study, simply having a romantic partner seems substantial, as those who are coupled report fewer drinking problems than their single counterparts. Fleming et al. [70] figured out that heavy drinking, marijuana usage, and cigarette smoking were linked to the dissolution of a romantic relationship due to the increased usage of these substances when switching partners within six months. Individuals establishing a new relationship or transitioning to a more committed relationship status did not show a decrease in substance usage. Those who went from being single to being in a romantic relationship smoked more cigarettes than those who did not change their relationship status [70]. Partners’ binge drinking behavior influenced respondents’ binge drinking behavior during young adulthood [80]. Blumenstock & Papp [86] demonstrated the interrelations between romantic relationship circumstances and drug habits. Relationship status, partner support, and partner presence at the moment are related to at least one form of substance use behavior [86, 98]. They also indicated that supportive partnerships are not universally protective against substance use in the college population. Aspects of romantic relationships like monitoring and partner antisocial behavior were consistent with substance use [98]. Furthermore, Fleming et al. [99] reported cohabiting relationships as a protective factor against substance use compared to singles.

3.2.6. Romantic Relationship Dissolutions

Break-up or romantic dissolutions are significant events among young adults that might cause implications for mental health. Rhoades et al. [71] investigated the probable impact of relationship dissolution on unmarried couples’ mental health and well-being. Although the overall effect sizes were minor, the findings imply that the end of a romantic relationship can be a substantial stressor since it was associated with increases in psychological distress and declines in how individuals assess their life satisfaction. A higher level of relationship quality before the break-up was connected with a lesser drop in life satisfaction after the break-up but not associated with changes in psychological discomfort. Living together and having marriage aspirations were strongly connected with greater drops in life satisfaction followed by a breakup. Mirsu-Paun & Oliver’s [81] meta-analysis showed a modest association between relationship variables (quality and break up) with depression/self-harm.

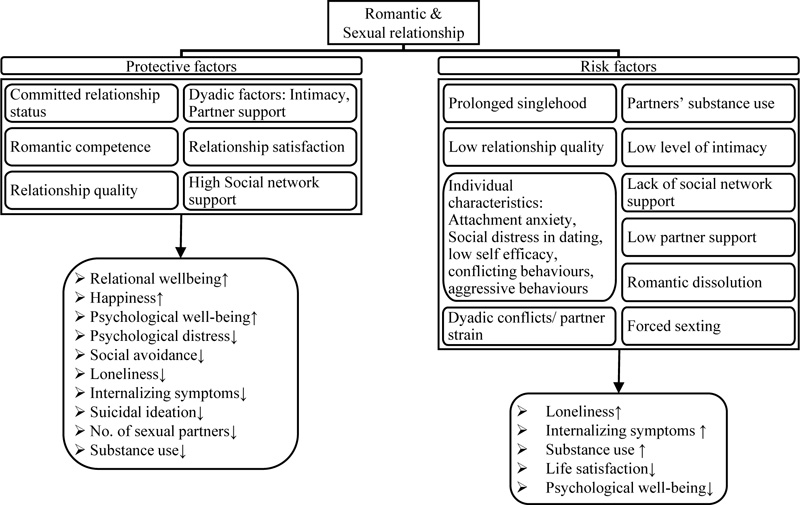

Simon and Barrett [69] investigated whether recent break-ups are related to the emotional well-being of young adults. Recent break-ups are associated with more depressive symptoms. However, the link between a recent break-up and depression is substantially more robust in women than males. Break-ups in the previous year are related to significantly higher substance abuse/dependence levels, and this association holds even when a current romantic involvement is included in the model. A recent romantic break-up is linked to higher levels of depression in women than in males, whereas a current romantic relationship is linked to fewer substance abuse issues in women. Fig. (3) presents a conceptual diagram of the risk and protective factors associated with romantic and sexual relationships affecting the mental health of young adults.

Overall, the studies examining the association between young adults’ romantic relationships and mental health demonstrated two sub-themes—protective and risk factors. We found several factors within one’s romantic relationship that positively and negatively impact one’s mental health and well-being. Current committed relationship, having good romantic competence, relationship quality and satisfaction, partner support and intimacy are identified as protective factors which enhance well-being and reduce clinical symptomatology and risk behaviors. In contrast, prolonged singlehood, lower intimacy, partner support, relationship quality, conflicts, substance use, and several individual characteristics like insecure attachment, lower self-efficacy, dissolution of relationship, and aggressive/conflicting behaviors are identified as risk factors. The risk factors increase the chances of experiencing loneliness, internalizing symptoms like anxiety and depression, substance use, and reduced life satisfaction and psychological well-being. The protective factors enhance happiness and psychological well-being and reduce psychological distress, suicidal ideation, loneliness, substance use, and risky sexual behaviors.

3.3. Peer Relationships

Peer and friendships are another important domain in the personal relationships for young adults. Sullivan’s [100] interpersonal theory stated the influence of friendships on one’s self-esteem, which is crucial, especially in young adulthood. Friendships may vary across their positive features, such as companionship, solidarity, and negative features, such as conflicts, rivalry, and dominance, and the extent of these features may predict individual psychosocial adjustments. In the case of college-going young adults and those who stay in hostels- who are not near parents, siblings, or romantic partners, peers and friends are critically important [101]. They interact most with their peers and often involve career decisions, romantic involvement, and changing self-conceptions [102].

Lapierre and Poulin [36] examined the link between friendship instability during emerging adulthood and depressive symptoms. According to their findings, friendship instability was strongly connected with depressive symptoms in young adulthood, but only among women who sought post-secondary education. Women’s friendships are more intimate and emotionally close than men’s— they explained particularly women who were concerned about losing friends due to the move to post-secondary education had a poorer adjustment to university and more feelings of loneliness and guilt. Miething et al. [103] examined friendship network quality and the psychological well-being of young people. They reported that friendship network quality and psychological well-being were positively correlated for both males and females. This relationship was more evident during late adolescence at 19 years and less pronounced at 23 years [103]. At the same time, friendship quality does not seem necessary for the well-being of romantically involved emerging adults— but it seems essential when in the phase of romantic dissolution [6].

Chow & Ruhl’s [34] study found that emerging adults who confront more friendship stressors are more likely to feel anxious and doubtful about their attachment bonds, which leads to increased depressive symptoms. Leadbeater et al. [104] investigated whether peer victimization predicts internalizing symptoms in young adult mental health. From adolescence to young adulthood (ages 12–27), patterns of physical and relational victimization are explored, as well as concurrent and prospective relationships between internalizing symptoms (depressive and anxious symptoms) and peer victimization (physical and relational). Results indicated that both types of victimization were linked to internalizing symptoms in males and females throughout young adulthood. In an 18-year longitudinal study, Heinze et al. [105] found that adolescent exposure to violence is linked to increased risk behaviors and mental health problems in young adulthood.

King & Terrance [106] evaluated the best friendship qualities with the closest non-romantic friend and MMPI characteristics. The majority of the MMPI-2 scales (10 of 13) correlated substantially with the participant’s tendency to consider their best friend as secure, trustworthy, and unlikely to produce feelings of humiliation or discomfort during the interaction. Bagwell et al. [107] tested if friendship quality is associated with clinical symptomatology and self-esteem, positive and negative changes (such as relationships growing stronger or becoming weaker or non-existent) associated with adjustment levels of the individuals. Findings showed robust associations between negative friendship features and clinical symptoms. They argued that young adults with high levels of friendship conflicts report high levels of symptoms, hostility, and anxiety. The negative association with interpersonal sensitivity was also reported, though marginally. Greater satisfaction in friendship also showed higher self-esteem and less feelings of hostility, whereas negative friendship contributed to higher anxiety, hostility and overall symptoms when positive features were controlled. Although most of the studies support that positive friendship features are linked to improved mental health, an interesting finding is that—a recent study by Roc [49] reported social support from friends being linked to increased depressive symptoms.

Discomfort in interactions with friends was found to be inversely related to self-esteem, positively related to interpersonal sensitivity (e.g., discomfort in interpersonal interactions, self-doubt, and feelings of inferiority), and marginally related to overall symptomatology and anxiety. Adverse changes in the relationship —relationship becoming weaker— in 1 year caused increased interpersonal sensitivity. A noteworthy conclusion was that negative features of friendship were stronger predictors of adjustment than positive features in friendships. Narr et al. [108] reported that close friendship strength during adolescence is significantly correlated with positive mental health changes during young adulthood and peer preference was predictive of higher levels of later social anxiety during young adulthood. Young adults who possess closer best friendships during their teen years later develop relatively lower depression symptoms, social anxiety, and relative increases in self-worth by their twenties.

Mendelson and Kay [109] indicated that young adults in imbalanced friendships had lower positive feelings about their friends and relationships. Apart from the negative consequences when friendships do not go well, literature also shows friendships’ supportive roles in maintaining psychological well-being. Lee and Goldstein [110] showed that support from friends buffered the association between perceived stress and loneliness among young adults when other sources like family and romantic relationships did not affect the study. Support from friends or peers may be instrumental in boosting an individual’s well-being and reducing levels of distress caused by stress as individuals evolve from adolescence to adulthood [110]. These empirical findings are consistent with the life course approach, which sets people’s relationships and meanings in a developmental context. (Table 4) presents an overview of the nature and details of the studies on peer relationships.

| Title & Year | Country | Research Design | Sample | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive feelings in friendship: Does imbalance in the relationship matter [109]? (2003) | Canada | Quantitative dyadic data, cross-sectional. | 94 pairs age between 17–32 years; 98% from 18 to 25 year | positive feelings for a friend and satisfaction with the friendship. Friend’s Functions (stimulating companionship, help, intimacy, reliable alliance, emotional security, and self-validation) Respondent’s friendship Functions Kind of friendship |

| Friendship quality and perceived relationship changes predict psychosocial adjustment in early adulthood [107] (2005) | USA | Longitudinal, quantitative. | Time 1= 51 dyads in 18-22 age range. Time2= 69 dyads |

Friendship quality Perceived Social Support individual adjustment observational assessment of friendship quality |

| Best Friendship Qualities and Mental Health Symptomatology Among Young Adults [106] (2008) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 398 college students | MMPI Friendship qualities |

| Close Relationships and Happiness Among Emerging Adults [6] (2010) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 314 young adults from a university | Relationship Quality and Conflict Happiness |

| Friendship and Romantic Stressors and Depression in Emerging Adulthood: Mediating and Moderating Roles of Attachment Representations [34] (2014) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 164 emerging adults age ranging from 18 to 21 years | Friendship and Romantic Stressors Attachment Representations depressive symptoms |

| It gets better or does it? Peer victimization and internalizing problems in the transition to young adulthood [104] (2014) | USA | Quantitative, longitudinal. five-wave multi- cohort study | 459 youth (15- 22 years old at T1 and ranged from 20 to 27 years old at T5) | Physical and relational peer victimization. Symptoms of internalizing problems |

| Friendship networks and psychological well-being from late adolescence to young adulthood: a gender-specific structural equation modeling approach [103] (2016) | Sweden | Quantitative, longitudinal. 2 wave study(at 19 and 23 years) | 772 youth | Friendship network quality Psychological well-being |

| Loneliness, Stress, and Social Support in Young Adulthood: Does the Source of Support Matter? [110] (2016) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 636 college youth (age range 18–25) | Perceived stress Sources of Social Support Loneliness |

| Friendship Attachment Style Moderates the Effect of Adolescent Exposure to Violence on Emerging Adult Depression and Anxiety Trajectories [105] (2018) | USA | Quantitative, longitudinal. 12 wave study | 850 youth (14-32 years) | Depressive symptoms Anxiety symptoms Adolescent exposure to violence Observed violence Victimization Family physical violence Friendship attachment Friendship support |

| Close Friendship Strength and Broader Peer Group Desirability as Differential Predictors of Adult Mental Health [108] (2019) | USA | Quantitative, longitudinal. | 169 adolescents followed over a 10-year period(ages 15 to 25) | Depressive Symptoms Self-Worth Close Friendship Strength Peer Affiliation Preference Self-Perceived Social Acceptance Social Anxiety Close Friendship Consistency |

| Friendship instability and depressive symptoms in emerging adulthood [36] (2020) | Canada | Quantitative, longitudinal. | 268 youth between 22 and 26 years | Friendship instability Depressive symptoms |

| Depression and Perception of Family Cohesion Levels and Social Support from Friends in Emerging Adulthood at a University Mental Health Clinic [49] (2020) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 372 participants (age range from 18 to 25) | Familial Cohesion Social support from friends Depressive symptoms |

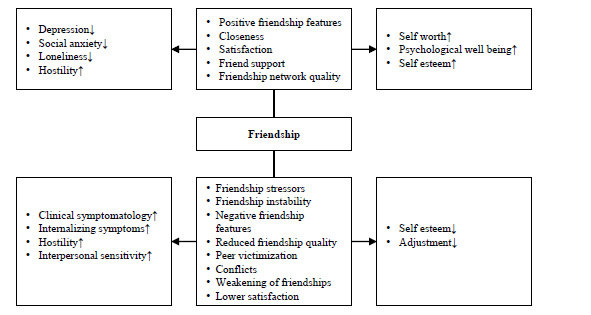

Our review of studies examining the association between peer relationships and mental health outcomes showed several sub-themes that promote or adversely affect mental health. Positive relationship experiences such as positive friendship features, support, closeness and satisfaction in friendships and friendship network quality enhance one’s self-worth, self-esteem and psychological well-being and reduce depression, social anxiety, loneliness, and hostility. On the other hand, negative friendship features, conflicts in friendships, poor friendship quality and peer victimization hamper one’s self-esteem and adjustment and increase hostility, interpersonal sensitivity, internalizing symptoms, and clinical symptomatology. Fig. (4) depicts a conceptual understanding of peer relationship features affecting the mental health of young adults. Unlike the other forms of relationships, such as family and romantic partners, the influence of peer relationships on one’s self-esteem is somewhat more evident. These findings demonstrate that acceptance in peer relationships is crucial in young adulthood, similar to adolescence [111, 112].

3.4. Interpersonal Relationships and Physical Health

Stressful interpersonal relationships, conflicts, or dissatisfaction can affect physical and mental health under conditions of allostatic load [14, 113], as the increase in stress hormones is linked to acute and chronic stress [12]. Research has shown mixed answers to whether personal relationships have implications on physical health. Berry et al. [14] conducted an exploratory study on the effects of relationship stresses on a physiological level by measuring the salivary cortisol levels. Testing personality traits, quality of interpersonal relationships, hormonal stress activity, and mental and physical health of undergraduate students in the U.S. reported that relationships were associated with mental health outcomes but not physical health. Although, through relationship quality— the personality component showed indirect effects on cortisol reactivity. Cortisol production increased when people reminisced about unhappy relationships —suggesting acute stress. They also reported having greater mental health issues but fewer physical illnesses. Similarly, Ford and Collins [32] reported rejection in personal relationships linked to significant reductions in psychological well-being but not physical health.

Women’s attachment avoidance also predicts cortisol patterns in young dating couples. Before and during a discussion about conflict with their dating partner, more avoidant female dating partners had higher cortisol levels, followed by a rapid reduction in cortisol shortly after the session, possibly offering physiological relief once they could disengage from the discussion [114]. In another research, by examining relationship experiences with parents and close friends during adolescence and blood samples 14 years later in young adulthood, Ehrlich et al. [115] showed how the quality of relationships with parents and friends in adolescence predicts metabolic risk in young adulthood. According to their results, females’ close and supportive relationships with their parents and male friends during adolescence minimized the risk of metabolic dysregulation in adulthood. Similarly, Women's levels of dysmenorrhea, or painful menstruation, are also influenced by social support [116]. Women with greater disruptions in their social networks had more menstruation symptoms than those with steady support. Losing positive and valued social ties can exacerbate or cause poor cognitive and emotional states, which could, in turn, impact menstrual symptoms, either directly on physiological mechanisms that produce perimenstrual pain or indirectly through behavioral practices that raise the chance of painful menstruation [116].

Braithwaite et al. [68] investigated the relationship status (committed/single) of college students and their health. According to the study, individuals in committed relationships had considerably lower overweight/ obesity scores than single participants. However, there was no substantial difference between the groups regarding physical health problems. People reported believing that their significant others have a more positive role than negative impact on their health. Partners positively influence by promoting healthy eating habits, physical exercise, medical help-seeking, self-esteem (especially for women), and maintaining personality traits/ characteristics that enhance health and well-being [117]. Men’s and women’s views of their significant others’ health influences were linked to their actual health results. Men’s perceptions of their significant others’ impact on their health were linked to their BMIs, physical activity, medical help-seeking, and drinking and smoking habits. Women’s perceptions of their significant others’ health influences were linked to their BMIs, physical activity, and drinking and smoking habits.

Seeman et al. [118] investigated social relationships and their biological correlates. Results indicated multiple areas of biological regulation, including cardiovascular, metabolic, inflammatory, neuroendocrine, and autonomic activity, are highly related to the quantitative and qualitative qualities of people's social networks. More close social interactions and reported frequency of receiving assistance from close family and friends are linked to healthier biological profiles, especially regarding inflammatory, metabolic, and autonomic risks. On the other hand, a greater frequency of reported social pressures (excessive demands, criticism from others) was linked to biological risk profiles.

| Title & Year | Country | Research Design | Sample | Outcome Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital stress: Immunologie, neuroendocrine, and autonomic correlates [12] (1998) | USA | Cross-sectional, quantitative |

90 newlywed couples | Marital problems Physiological changes |

| Disruptions of Social Relationships Accentuate the Association Between Emotional Distress and Menstrual Pain in Young Women [116] (2001) | USA | Longitudinal, qualitative. | 184 women | Social Support State-Trait Anxiety Depression Menstrual Symptoms |

| Forgivingness, relationship quality, stress while imagining relationship events, and physical and mental health [14] (2001) | USA | Cross-sectional, quantitative |

39 undergraduate students - ages ranged from 18 to 42 years. (M = 22.9) | Personality traits associated with forgiveness and unforgiveness Relationship imagery Quality of interpersonal relationships salivary cortisol current mental and physical health |

| Romantic Relationships and Health: An Examination of Individuals’ Perceptions of their Romantic Partners’ Influences on their Health [117] (2007) | USA | Cross-sectional, quantitative. | 105 couples | Romantic partners' influences on health level of love and conflict weight status participation in physical activities general health status alcohol consumption and smoking behaviors general stress |

| Romantic relationships and the physical and mental health of college students [68] (2010) | USA | Cross-sectional, quantitative, | 1,621 college students (18 to 25 years) | Relationship status Mental health problems Physical health problems Overweight/obesity Risky behavior (sexual and substance use behavior) |

| Social Relationships and Mortality Risk: A Meta-analytic Review [120] (2010) | - | Meta-analysis | 148 studies | aspects of social relationships risk for mortality |

| Self-esteem Moderates the Effects of Daily Rejection on Health and Well-being [32] (2013) | USA | Quantitative, cross-sectional. | 101 undergraduate (age 17 to 22) | Trait self-esteem Neuroticism Daily feelings of rejection General Mental Well-being Daily Health Behaviors Health-related Outcomes |

| Social relationships and their biological correlates: Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study [118] (2014) | USA | Longitudinal, quantitative. | 115 black and white men and women aged 18–30 years | number of close friends or close relatives relationship quality 17 biological parameters |

| Attachment and health-related physiological stress processes [114] (2015) | - | Review. | - | Attachment Physiological stress Health. |

| Quality of relationships with parents and friends in adolescence predicts metabolic risk in young adulthood [115] (2015) | USA | 14-year Longitudinal, quantitative | 11,617 adolescents through young adulthood (24 to 32 years) | Parent-child relationship quality Peer relationship quality Metabolic risk index |

According to cross-sectional research of adults, valuing friendships was linked to increased functioning, especially among the elderly, but valuing familial bonds had a consistent effect on health and well-being throughout life. Only strain from friendships predicted greater chronic illnesses during six years in a longitudinal study of older persons; support from spouses, children, and friends predicted greater subjective well-being over eight years [119]. Several prospective studies even tested how social relationships affected individual mortality. People who had greater social relationships had a 50% higher chance of survival than those with lower social relationships [120]. Although this review focus on young adults, we also have quoted a few studies which address the general population. We retained these studies as the mechanisms linking interpersonal relationships and the physiological process might not be very different. An overview of studies linking interpersonal relationships and physical health is presented in Table 5.

3.5. Scarcity of Personal Relationship Research in non-Western Cultural Context