REVIEW ARTICLE

The Experiences of Families Raising an Autistic Child: A Rapid Review

Boitumelo K. Phetoe1, Heleen K. Coetzee1, Petro Erasmus1, Wandile F. Tsabedze1, *

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2023Volume: 16

E-location ID: e187435012304040

Publisher ID: e187435012304040

DOI: 10.2174/18743501-v16-e230419-2022-100

Article History:

Received Date: 20/10/2022Revision Received Date: 20/01/2023

Acceptance Date: 23/01/2023

Electronic publication date: 09/05/2023

Collection year: 2023

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode. This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background:

Autism is becoming more prominent in South Africa and in the rest of the world. A family raising an autistic child plays a key role in the treatment and lifelong management. This responsibility goes with demanding challenges, which are unique to every child and situation. A deeper understanding of the psychosocial experiences and impact of autism and its symptoms on the involved families is ultimately essential in the development of relevant and scientifically based interventions and support programmes.

Objectives:

The aim of this review was to conduct a rapid review to explore, synthesise, and integrate existing scientific literature on the pre- and post-diagnostic psychosocial experiences of families that raise an autistic child.

Methods:

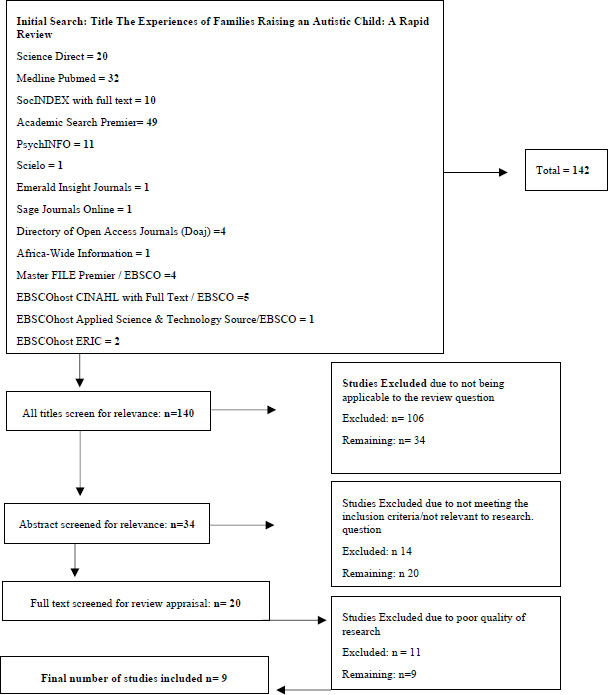

A comprehensive and systematic keywords search were conducted, and 142 relevant studies were found. These studies were then screened for relevance with regard to inclusion and exclusion criteria. Nine articles, published between 2008 and 2018, were identified for final inclusion in the study. Data were analysed using a thematic synthesis approach.

Results:

The thematic synthesis revealed three main themes and ten sub-themes that were anchored on families’ psychosocial experiences of raising an autistic child, both pre- and post-diagnosis. The themes include psychological experiences (emotions experienced, grieving process, parenting, and family dynamics), social experiences (lack of support services, and social awareness), and psychosocial coping strategies (isolation, information seeking, meaning-making, and support system).

Conclusion:

The analyses and synthesis of the identified articles indicated that the identified psychosocial experiences of families raising an autistic child were multidimensional and fit well within a contextual and systemic perspective. The family quality of life (FQOL) framework provides a positive approach that seeks to improve and optimise the quality of life of families that raise a child with a disability. It is recommended that families need to be informed of services available for autism and psychosocially supported so that they feel empowered to deal with the challenges at hand.

1. INTRODUCTION

Autism is becoming more prevalent both internationally and in South Africa [1]. Globally, one in every 160 people is estimated to be living with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [2]. Scientifically sound, accessible, and relevant support services have been indicated as a definite need of families that raise an autistic child [3-5]. A deeper and better understanding of the impact of autism and its symptoms on the involved families is indicated as essential to the management of the child and the family as a whole [6-8].

ASD is characterised by persistent difficulties with social communication and interaction, as well as the presence of restricted and repetitive behaviours, interests, or activities [9]. These difficulties have a significant lifelong impact, not only on the development of the individual but also on the family [10]. A study conducted by Nealy, O’Hare, Powers, and Swick [11] explains that the impact of autism on a family is significant and is experienced on mainly two levels. The first level is pre-diagnosis, where the unknown and uncertainty about what is going on are prominent. The second level is post-diagnosis, where the uncertainty and apprehension of what the diagnosis entails and what will happen next are prominent. Families are an integral part of the management of these experiences as they normally are the first to detect symptoms and make choices about early interventions [12]. What complicates this experience is the fact that there is no single behaviour indicative of autism, nor will any child show all of the disorder’s deficits at any given point in time [13]. There is thus not one set of guidelines or rules that will work for each autistic child, which intensifies the burden on the family to find a unique solution to their child’s specific needs.

The recent global increase in the prevalence of autism is in a large part attributable to changes in reporting practices [14]. This may be due to better awareness and the broadening of diagnostic criteria [15]. However, early diagnosis of autism remains rare, especially in certain disadvantaged communities [16]. This is exacerbated by the fact that indications of most spectrum diagnoses and the essential symptoms are unfortunately only noticed around the age of six years and older [17]. A study [18] by McKenzie et al. (2015) found that prior to diagnosis, many families may suspect something is not right with their child, but they do not report their suspicions due to a lack of knowledge and understanding of normal developmental patterns, as well as of autism and its symptoms [19, 20].

According to Meirsschaut, Roeyers and Warreyn [21], the fact that ASD is still considered an unusual disorder has a significant impact on families’ reaction to the diagnosis, as well as the post-diagnostic management of the child. Studies [22, 23] indicate that post-diagnosis, the economic and educational status of the parents play a vital role in the management of ASD. Parents from low-income households with limited education may not fully understand the developmental challenges their child is experiencing [22, 23]. Additionally, professional help or assistance might not be readily available or accessible, which has disadvantageous effects on several areas of family functioning, such as adding extra strain on the parents (individually), marital relationships, as well as sibling relationships [24]. This highlights the need for scientifically based and effective early interventions that will give relevant support also in under-resourced communities.

It is clear that autism has a significant impact on the psychological and social experiences of caretakers and families that raise an autistic child. The psychological impact on caretakers and families includes denial, emotionality, misinterpretation of the diagnosis, anger, disinterest, dislike, and uncooperativeness towards the professional [12]. Nissenbaum, Tollefson, and Reese [19] add that parents of children with autism have a greater risk of suffering psychological distress as they experience increased stress, depression, parental burnout, concerns about their child’s dependency, the effect on family life, poor physical health, and future psychosocial problems [12]. Furthermore, a lack of applicable and relevant educational resources (schools, teachers, and learning material) and support also add to the emotional strain on the parents. Few schools are accommodative of children with autism, which results in most children with autism remaining at home, which places their education as the sole responsibility of their caregivers [22]. This normally results in one parent being the primary caregiver, quitting a job reducing the much-needed family income [25].

The social impact on the family is mainly based on the reaction from friends and extended family members. Poor societal awareness causes families to feel judged and isolated because of their child’s diagnosis/condition [16, 20]. It is also indicated that raising an autistic child results in families giving up normal family routines and socialisation practices, as well as having difficulty maintaining employment [26, 27]. Over and above the aforementioned challenges faced by families of children with autism, limited sensitivity and accessibility in the public health and education sectors in Africa and South Africa intensify the parents’ experiences of not being understood or helped [3, 28].

In South Africa, it is indicated that one in every 86 children from the Western Cape is affected by autism [6]. Few studies have been conducted in the rest of South Africa or even sub-Saharan Africa, but as autism is said to be found in every ethnic and social group, it can be predicted that it is unlikely that the statistics will be any lower in other provinces [3, 7, 8]. It was also found that in South Africa, cultural explanations and interpretations of certain spectrum symptoms complicate the diagnostic and treatment processes. These cultural prejudices play an important role in the psychosocial experiences of the involved family [29-33]. Some of these beliefs include the belief that the child’s illness was brought about by ancestors as punishment for the family’s wrongdoings or that the child’s behaviour is linked to potential messages from their ancestors, while other beliefs link their child’s symptoms to supernatural causes or ascribe the illness’ causation to external supernatural forces [34]. While most parents explore different cultural methods of diagnosing and healing with the aim of gaining a better understanding of their child’s functioning [33], several studies suggest that 60% of the South African population would rather make use of traditional medicine and consultations with traditional healers in an attempt to gain a better understanding of their problem [35]. Which leads to delayed diagnosis and intervention, by the time the diagnosis is made, a child has lost a significant amount of time to fully benefit from intervention. Therefore, the interventions received are viewed as inadequate [36]

South African families that raise an autistic child are reportedly experiencing significant challenges in terms of proper intervention programmes and educational services [3, 29, 30]. This has resulted in a high level of dissatisfaction with disability-related government support, which includes health, financial, and psychological services [30]. Families are left feeling as though they are isolated, alone, and in a state of ‘crisis’. [31, 32]

Taking the abovementioned statistics and information into account, it could be deduced that a high number of families in South Africa are faced with unique challenges in caring for children diagnosed with autism [37]. These families need appropriate and relevant services based on relevant and scientifically sound knowledge [38]. An integrative understanding of the experiences of these families is therefore critical, as it provides insight into their unique challenges, daily realities, and the impact of autism on family dynamics. This study focused on integrating what previous studies have found to be the pre- and post-diagnosis psychosocial experiences of families affected by the diagnosis of autism, internationally and in South Africa. This information will be valuable in informing mental healthcare providers about the development and implementation of appropriate and much-needed support services and intervention plans. The research questions for this study were as follows:

(1) What are the pre- and post-diagnosis psychological experiences of families that raise an autistic child?

(2) What are the pre- and post-diagnosis social experiences of families that raise an autistic child?

2. THE RATIONALE OF THE STUDY

From the abovementioned literature, it is clear that having a child with autism affects and influences families and the broader systems the families find themselves in. It is furthermore clear that the challenges and stressors associated with raising an autistic child can significantly reduce the prognosis for effective interventions. It is important to explore families’ experiences in raising an autistic child in order to inform sound and scientific interventions and support programmes that can improve service delivery to these affected families.

An integration of what previous studies found to be the main experiences of families affected by the diagnosis of autism, internationally and in South Africa, will be valuable in providing appropriate, relevant, and scientifically sound knowledge to inform professionals who develop support and intervention programmes aimed at enhancing the psychosocial wellbeing and quality of life of families that raise an autistic child. This information could also be valuable in informing policies, structures, and procedures developed to effectively manage children with autism in the South African health and educational sectors.

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

A rapid review was conducted to answer the research questions. This consisted of systematic and explicit search and review methods that enabled the reviewers to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant studies to include in this study [39].

3.1. Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

A rapid literature search was conducted. EBSCO Discovery Service (EDS) provides access to national and international books, journal articles, and online resources from more than 60 databases. This includes databases such as Academic Search Premier, PsycArticles, PsycInfo, and Science Direct. The abovementioned databases contain accredited articles and provided the researcher with broad access to relevant scientific literature. Google Scholar was also used as one of the search engines to ensure thoroughness.

3.2. Search String

Level 1 (Title): experiences; perceptions; narratives; attitudes; views

Level 2 (Abstract): families; parents; mother; father; guardian; caregiver

Level 3 (Abstract): raising; upbringing; raise; caring; care

Level 4 (Abstract): autism; ASD; autism spectrum disorder; Asperger’s; Asperger’s syndrome; autistic disorder

Level 5 (Abstract): child*

3.3. Selection Criteria

Full-text journal studies, peer-reviewed studies, review studies, PhD theses, and master’s dissertations/mini-dissertations were included. Non-peer-reviewed studies, conference proceedings, and studies published in languages other than English were excluded. The search was limited to studies published from 1980 to 2019 because the first DSM that included infantile autism was published in 1980 [40]. However, the search string only produced studies published between 2000 and 2019.

The search string and criteria produced a total of 142 results of potential studies. The researcher screened the 142 article titles for relevance, after which 140 studies were identified with relevant titles. Of that 140, 106 studies were excluded due to inapplicability to the review question.

The abstracts of the 34 studies that remained were then independently reviewed by the researcher and the study co-authors. This was done to select those to be included for further analysis. Of the remaining 34 studies, 14 studies were further excluded due to them not meeting the inclusion criteria or being irrelevant to the research question. Studies excluded only explored one theme and did not encompass the whole experience, such as the role of stigma, sibling relations, and cultural perceptions. This resulted in 20 studies remaining, which were independently and critically appraised by both the researcher and co-authors. A further 11 studies were excluded during the appraisal process due to poor quality of research methodology or ethics. Finally, nine studies were identified as studies that would be reviewed to explore the research question.

3.4. Appraisal Process

In the appraisal process, the guidelines as provided by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018) were integrated with the guidelines of the Joanna Briggs Institute (2014) for qualitative and quantitative studies. The integrated appraisal instrument consisted of the following questions:

(1) A clear statement of the aims of the research?

(2) Did the research receive ethical approval?

(3) Valid and reliable measurement?

(4) Is data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

(5) Is the sample representative of the population?

(6) Bias has been minimised in the selection of cases?

(7) A clear statement of findings?

The 20 articles were independently appraised by the two researchers. Articles that were considered of high quality were given a score of above 5. However, most studies chosen for the study were scored 7, with the highest scoring 8, by both reviewers using the appraisal checklist. The two researchers compared their scores for the identified articles and came to an agreement on which articles should be applicable and relevant to include in the review. No disagreements occurred between the reviewers. Only sufficiently qualified articles were included in the analysis as reflected in Fig. (1). Upon application of a rigorous search, exclusion, and appraisal process, a total of nine studies remained to be explored, reviewed, and analysed in order to answer the research question. The whole process of selecting the final nine studies included in the study is reflected in Fig. (1).

3.5. Data Synthesis and Analysis

A thematic synthesis was conducted in order to inductively analyse the findings from the nine retrieved studies. Thomas and Harden’s (2008) [41] steps were used in order to do this. These steps involved becoming acquainted with the data and preliminarily coding the findings. Thereafter, themes were identified, reviewed, given their final labels, and described.

|

Fig. (1). Selection process. |

The data-extraction process was carefully planned in order to ensure that data were extracted accurately. For further contribution to the accuracy of the study, both the researcher and the study leader read all the included studies [41]. This process was independently conducted by the researcher and study leader in terms of exploring, summarising, and synthesising the findings from the selected studies. The following three stages were followed: line-by-line coding of the findings, organisation of findings into related areas to construct/descriptive themes, and development of analytical themes [41].

4. ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

As this study did not carry any risks, ethical clearance was sought from the Community Psychological Research (COMPRES) before the research commenced. Research approval was also obtained. In addition to adhering to the research protocol, the authors applied the guidelines provided by Wagner and Wiffen [42] to ensure accuracy and transparency, as well as to avoid duplication, fabrication, falsification, and plagiarism. Validity and reliability were promoted by following the steps in the research process in a thoughtful and reflective way. Furthermore, only articles that received ethical clearance or served as no-risk studies were included in the review. In order to ensure the credibility of the data, crystallisation was utilised; this meant that more than one reviewer worked on the material as each reviewer has a different viewpoint, in order to discover similar themes [43]. The use of four reviewers further ensured and enhanced the trustworthiness of the study.

The researcher and study leader worked together in the review process [43] Appropriate citations were included in order to acknowledge the authors of the studies. Furthermore, the study was submitted to Turnitin software, which tested the study for plagiarism.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Study Selection

The nine studies that were included in this study varied in sociocultural contexts and locations. The families in the studies included mothers, fathers, and caregivers that raise a child diagnosed with ASD. The studies typically involved focus groups, in-depth interviews, anthropological fieldwork, and self-administrated questionnaires as the data-gathering methods. The autistic children in the identified studies were between low and medium functioning and ranged between the ages of five and 18 years. The research designs of the articles included in the review are outlined as follows: six qualitative designs, one mixed-methods design, one quantitative design, and one qualitative meta-synthesis. The studies included in this review used data from three different continents which includes Africa, Europe and North America and five different countries, namely Canada, Ireland, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. It is interesting to note that three of the studies [44-47] specifically focused on fathers of fathers raising an autistic child. These studies are especially valuable as fathers’ experiences were previously neglected and not considered [44]. To gain a holistic understanding of the whole family’s experiences in raising an autistic child, it is important to incorporate the experiences of the mother, father, and any other primary caregivers, as well as the siblings.

After analysing and synthesising the articles, the following themes and subthemes emerged from the data. These themes were identified against the backdrop of the research questions focusing on pre- and post-diagnostic psychological and social experiences of families that raise an autistic child (see Table 1).

|

Psychological Experiences (Pre and Post Diagnosis) |

Social Experiences (Pre and Post Diagnosis) |

Psychosocial Coping Strategies (Pre and Post Diagnosis) |

|---|---|---|

| • Emotions experienced • Grieving process • Parenting • Family dynamics |

• Lack of support services • Social awareness |

• Isolation • Information seeking • Meaning-making • Support system |

6. THEMES FROM INITIAL CODING

6.1. Psychological Experiences: Pre and Post-diagnosis

On a psychological level, the impact on caretakers and families that raise an autistic child is multidimensional [48-54]. The analysed and synthesised literature indicated that on a psychological level, the families’ experiences centred around a variety of emotions experienced, as well as the experience of loss/grief. This is also evident in the psychological effects of uncertainties about parenting roles and a psychological shift in terms of family dynamics.

It is interesting to note that the psychological experiences differ pre- and post-diagnosis. The pre-diagnostic experiences are often negative as the parents verbalise the emotional strain of uncertainty and fogginess in not understanding their child’s behaviour [20, 49, 50]. This process is also verbalised and compared to the process of losing their ‘normal’ and ‘ideal’ child and experiencing uncertainty with regard to what to do next [20]. Post-diagnosis, they experience a loss of their ideal parental experience, which means adjusting their parenting style and an adjustment of their family dynamics [20]. This then creates a shift from more negative emotions to more positive emotions, as families adjust to the child’s condition and understand the child better [49, 50]. The abovementioned process is elaborated on in the following subtheme descriptions.

6.1.1. Theme 1: Emotions Experienced

The emotions experienced by families that raise a child with autism are broad and extensive. The emotions also vary depending on the phase of diagnosis and treatment the family find themselves in. It is noticeable that emotions experienced during this process vary on a continuum from negative to positive [47, 49].

Studies conducted among families indicated that pre-diagnosis, families experience vast negative emotions such as confusion and helplessness [20, 52] as they suspect that something is wrong with their child; however, due to the absence of physical features in autism, families are faced with the inability to understand their child’s behaviour [50, 51]. In some instances children displace a lack of communication, inexplicable anti-social behaviours, and tantrums which makes it difficult for parents to understand their child [40]. All these generate high levels of anxiety, parental stress, as well as general psychological distress [46-48]. Therefore, in order to attempt to make sense of everything, families start having numerous medical consultations with different professionals [52]. This means that families must process different emotions attached to the process, which include feelings of confusion, anger, and helplessness [49, 51]. Although the idea of finding an answer gives a feeling of hope, the fact that the child has a problem that they might never understand results in further increased feelings of distress [45]. The unfamiliar medical jargon and an overwhelming amount of new information, combined with the difficulty of finding the appropriate and relevant support services, contribute to an overwhelming feeling of confusion, which causes parents to internalise blame and feelings of guilt [48, 49, 52].

Upon receiving the diagnosis of autism, it is indicated that families experience pronounced emotional distress, which includes shock, despair, and devastation [20, 47, 49, 52]. Studies have indicated that a lack of knowledge/understanding of the disorder, as well as the lifelong nature of the diagnosis, contributes to the fact that the news that they have a child with autism is viewed as ‘devastating news’ by families [20, 45, 51, 52]. Some parents reported total surprise and dismay as, according to them, their children did not display any usual behaviours that might be expected from children with autism [49, 51].

After receiving a diagnosis, parents start to think about the causes of autism, which results in feelings of blame towards themselves [45, 51]. This blame is often wider than an individual experience as one of the studies indicated that parents also experience blame from society and people outside their family, including healthcare professionals [20, 48]. Cultural and religious beliefs also play a role as parents attempt to make sense of the diagnosis; these beliefs include parents linking the cause to black magic which is associated with witchcraft and punishment from God, and often ancestral rejection for moving far from family or not performing certain cultural rituals for the child [51].

Thereafter, families start experiencing feelings of anger, depression, and despair. It was found that this anger was mainly directed at healthcare professionals [48-51]; firstly for making a diagnosis, and secondly for not ‘taking their concern seriously and acting sooner than later’ [45]. A study conducted by Woodgate, Ateah and Secco [20] stated that in this phase, parents also experience feelings of loneliness and isolation. They describe raising an autistic child as ‘living in our own world’, their lives as ‘an endless routine of treatments and therapy’ and missing having what they describe as ‘a normal life’ [50, 52].

It is also important to mention that some studies do mention some positive emotional experiences upon receiving the diagnosis, which includes feelings of relief upon hearing the diagnosis, as they have something that explains their child’s condition, which finally clarifies their concerns [20, 48, 50]. Furthermore, studies indicate that post-diagnosis emotions are associated with greater levels of understanding and acceptance of the child’s situation, as they become more patient and understanding, which allows them to experience more moments filled with joy [47, 50, 52]. Studies have indicated that receiving the diagnosis is a stepping stone as it allows parents to begin coping with it and to reconcile any feelings of guilt they had pre-diagnosis [48, 52].

6.1.2. Theme 2: Grieving Process

The experience of grief and loss is prominent in the synthesis of the psychological experiences of families that raise an autistic child [20, 46, 48, 49, 51]. It is indicated that the lack of knowledge about the normal developmental behaviour of their child, combined with the absence of any visual features of autism, makes it difficult for families to identify that there is a real problem with their child’s functioning and behaviour. The gradual or sometimes sudden realisation that something is wrong creates a feeling of loss, which leaves the families to grieve and feel that they are losing their child and cannot do anything about it [49, 51, 52].

Studies compare this emotional process to the Kubler-Ross stages of grief, which entail the different phases of denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance in pre- and post-diagnostic experiences of the involved families. It is important to note that these phases do not always follow in chronological order and that each individual will experience their grief uniquely [20, 52].

During the pre-diagnosis stage, the absence of physical and medical symptoms and a lack of knowledge pertaining to normal development and autism often create a safe space of denial for the families and caretakers [44, 50]. This involves families attempting to make sense of the child’s behaviour by justifying the child’s behaviour, e.g. ‘The child is just too quiet’, or comparing the child with other family members, e.g. ‘The father was late to develop, yet still turned out fine’. Pre-diagnosis, families use denial as a defence mechanism to deflect the built-up anxiety that something might really be wrong with their child. After the diagnosis is made, the denial is used to soften the initial shock and to pretend that perhaps the diagnosis is not true or accurate [48, 52].

In the next phase, families mention feelings of anger. This anger is mainly experienced due to feelings of frustration and helplessness because they do not know what they can do to assist their child. [46, 52, 51] Some studies suggest that this anger is often directed towards the parents themselves for not being able to ‘fix’ their child [20, 45, 51] and for not identifying the symptoms earlier to proactively help their child.

In the depression phase, it is indicated that parents go through a phase of severe sadness as they feel the loss of their ideal child and their ideal parental experience [20] by ‘mourning their normal child’ and ‘the life they envisioned’. [47, 49] Families express that instead of looking forward to their children going to college, getting a job, and becoming a spouse, families now face a future of economic, emotional, and family cohesion challenges [20, 47, 50]. In one study [49], a parent defined the diagnosis as ‘death in your family’ and stated: ‘You still have that person here, but something dies.’ Other parents stated: ‘Your world falls apart and what dreams you have for your child are gone.’ Parents expressed the diagnosis as having a ripple effect, as the initial diagnosis was the time when the loss was felt the greatest, but the sense of loss continues throughout a lifetime, which is also felt by the family [20, 48, 50].

During the bargaining phase, families indicate that they start bargaining and asking questions with the aim of seeking answers to understanding and managing their child’s problem [45]. In some cases, this bargaining process is linked with existential questions with regard to religion, spirituality, and faith [20, 45, 51]. Caretakers indicated that during this time they struggled with questions such as: ‘Is my lack of belief in ancestral connection the reason for my child’s behaviour?’, ‘Is my neglect of traditional and spiritual rituals the reason for my child’s diagnosis?’, and ‘If I start to do everything my religion/God asks of me, will my child be healed?’ [49].

The identified studies indicated that the progression through the stages of grief guided the families to the finale phase of acceptance. Ultimately, most families come to accept the disability as being part of the family, therefore putting all other emotions behind them and working to better their lives and the lives of their children [20, 45, 48]. Some even indicated that after moving through all these phases of grief, they could eventually manage to find some true meaning in the fact of having a child with autism [45]. Some families indicated that this phase of acceptance made them realise that ‘they had to go through the feelings of anger and blame so that they can get to a point where they accept their situation and can cherish moments of joy brought by their autistic child’. [20] In the acceptance phase, families indicated that they experienced new energy and capacity to start exploring resources to assist their child [20, 46].

6.1.3. Theme 3: Parenting

Research is clear on the fact that parenting children is challenging and psychologically and emotionally taxing on parents [22]. When developmental difficulties and deviances are present, the pressure on the parents, as well as the challenges they must deal with, are even more exhausting [19]. The analysed studies identified the knowledge of different parenting styles, the capacity to adapt, and the effective application thereof as mentionable psychological stressors to the parents and families of autistic children [20].

Pre-diagnosis, families expressed that due to indicators of the disorder often being unclear and vague [52], they did not modify their initial parenting style, which caused severe distress to themselves, as well as to their autistic child. The unpredictability and rigidity in their autistic children’s reactions towards their parenting attempts left them in a total state of uncertainty and increased vigilance [20]. Post-diagnosis, families had to start adjusting their parenting style, with the aim of dealing with and managing the uncontrollable and unpredictable tantrums and aggression of their autistic child [52]. They had to adapt and venture on unfamiliar terrain in attempting to deal with uncontrollable and unpredictable behaviour, and navigating their approach and style in search of answers [48].

At the beginning after receiving the diagnosis, families reported heightened levels of vigilance, saying that it felt as if they were ‘walking around on eggshells’ [20]. They wanted to meet their child’s needs and protect them from any form of distress but really did not know what they were supposed to do. The analysed studies indicated that most parents reported that having a strict and predictable routine increased their watchfulness and preparation for anything [48] and made it much easier to manage and predict their autistic child’s behaviour. These strict and predictable routines decreased the parental stress experienced and, according to a study by Kayfitz, Gragg, and Orr (2010) [50], both mothers and fathers reported more positive experiences and lower levels of parenting stress. On the other hand, these strict and predictable routines also increased the psychological burden on the parents as they had to be prepared and consistent the whole time. They reported that it left no room for any daily changes and even normal mood fluctuations within themselves and that they had to change into ‘robots’ to keep their child safe and contained [48]. In one study conducted among fathers, one father expressed that he viewed parenting an autistic child as ‘stressful, scary, frustrating, but most amazing’ [46].

In summary, the identified studies indicated that although the initial experiences of parenting an autistic child were stressful and unpredictable, the positive rewards and outcomes when they tried something new were immeasurable. They indicated that they learned that adapting to new and creative ways of parenting was a valuable experience of growth for them as parents.

6.1.4. Theme 4: Family Dynamics

On a psychological level, systems theory indicates that if one part of a system is malfunctioning or changes its patterns of functioning, it inevitably affects the whole system [53]. In raising an autistic child, the initial pre-diagnosis lack of understanding of the child’s behaviour, as well as the mandatory adjustments and changes that occur post-diagnosis, inevitably impact the family’s daily interactions and dynamics [49]. When analysing the data for this study, two main subthemes with regard to the affected family dynamics emerged. The first subtheme focused on the disruption of family cohesion, and the second subtheme focused on the time involved in raising an autistic child. Furthermore, engagement with extended family members is limited as the child’s unpredictable behaviour can result in family members isolating themselves from family gatherings [46, 50].

During the pre-diagnosis phase, confusion and uncertainty result in families spending a great deal of time looking for answers and consulting with professionals in the process of attempting to understand their child [20, 48]. Family cohesion is disrupted as the time and energy that were previously used for one-on-one interactions with the spouse, other siblings, and family members are now solely allocated to the demands of understanding and seeking help for one child [52]. Family cohesion and connection are directly impacted by this focused attention and the ripple effect thereof has an influence on various dimensions of family cohesion and functioning [48, 49].

Post-diagnosis, the knowledge of what is going on and especially what autism is all about helps family members to understand why the sacrifices are being made and more clarity is gained on what each one’s role and expectations within the family system are. The reality, however, is still that many changes and adaptations must be made by all the other family members to accommodate one child. One father summarised this as follows in a study: [46] ‘Everything is then focused around, um, the child with ASD, so the other kids in the family, or the family unit then basically has to conform to the needs of, or the demands then of [the child with ASD] … And we all have an element of, I guess, sacrifice when it comes to that.’ Parents reported their other children feeling as if they were not treated the same as the child with autism [48]. It is, however, also indicated in the analysed studies that as families progress through the process of attempting to understand and adapt the system accordingly, they start realising the importance of having a life that is not solely focused on helping their child with autism develop to their full potential [48]. They mentioned that there is a process where they become aware of the importance of creating a balance between parenting their autistic child and engagement with their other children and family members [49, 52]. Interestingly, it was reported that caring for an autistic child can also have some positive effects on family cohesion. A study [46] indicated that mothers were often the prime carers and therefore had to sacrifice their professional life to take care of their child’s needs, while fathers worked long hours to take over the financial responsibilities of the family. Relying on each other and viewing their significant other as their ‘main, or sole, source of support’ [52] therefore assists in building family cohesion. In one study, parents expressed that as time progressed, the care for their autistic child became a team effort, thus enhancing family cohesion and meaning-making in the process of helping and guiding their autistic daughter/son/brother/sister. It is indicated that as the process of acceptance continues, the autistic child also finds their own unique role within the family, and the previously neglected siblings are often protective and supportive of their autistic brother/sister. A new family identity is formed in the fact that they are different from other families, which further enhances family cohesion [20].

Within the second subtheme of time consumption, it is prominent that the pre-diagnostic process of attempting to find answers takes up a great deal of family time. Days and hours are spent in the consultation rooms and test facilities of professional people and the whole family’s routine and schedules are organised around these appointments. Not only do the physical appointments take a great deal of time, but the proper preparations and arrangements to keep the autistic child calm and content to prevent a build-up of frustration and meltdowns take a toll on the whole family, which directly affects time spent together and with other family members and siblings involved [48].

Upon receiving the diagnosis, it was interesting to note that parents started scheduling time for themselves as they indicated that they felt frustrated by the lack of time they had for themselves and their families, thus leaving them feeling overwhelmed by family demands [45]. They expressed that scheduling ‘own time’ and ‘family time’ prevented them from feeling overwhelmed and built a capacity for them to be able to deal with unexpected and difficult situations [48]. One mother indicated in a study [20] how valuable it was for their whole family when she scheduled her autistic daughter’s therapy sessions around her normal, developing son’s hockey matches so that they could ensure that the whole family attended his matches and that organising and scheduling time made it possible for everyone in the family to attend.

Families expressed that autism affects both family cohesion and family time both pre- and post-diagnosis [20, 49]. Families, therefore, expressed a need to find a balance and make time not only for family members but for the caregiver as well. Autism is a lifelong diagnosis [48, 52] and creating and maintaining a balance within this context are crucial. It is also indicated that communication and relying on one another as a family have a valuable influence on family cohesion and each family member’s experience of their sense of belonging [46].

6.2. Social Experiences: Pre- and Post-diagnosis

The literature is clear on the definite effect that raising an autistic child has on the social experiences of the family and caretakers involved [52]. Social psychology theories emphasise the importance of social interaction, social coherence, and a feeling of belonging [53]. When an autistic child is introduced into a system, all the levels of the system’s functioning are impacted [22]. Everything on a social level that was comfortable, familiar, and helpful to these families changes because they are isolated and stigmatised and left in the dark to cope on their own [48]. The social experience themes and subthemes that emerged from the analyses and synthesis of the identified articles are: (1) the lack of relevant and proper support services, and (2) a lack of general social awareness and stigmatisation. It was also interesting to note from the literature that proper social interaction, connection, and support were identified as some of the most powerful coping mechanisms in these difficult times.

6.2.1. Theme 5: Lack of Care Services

In the analysis of the identified articles, it was clear that families that raise an autistic child felt that on a social support services level, nothing came easy and that pre- and post-diagnosis they had to ‘fight all the way to be recognized and to be helped’. They stated that they felt the government system (referring specifically to the health and educational sectors) was not geared to cater for people with autism, leaving them alone, isolated, and self-reliant [47].

Within the health sector, it was noted that as soon as they started realising that something was not right with their child (pre-diagnosis), they started searching for answers [46, 47, 49, 51, 52]. This entailed countless appointments with different healthcare providers. In some cases, they immediately got the answers they needed [48]; however, for the majority of parents the search for answers took longer. Socio-economic status and the unavailability of proper diagnostic services and facilities resulted in general ignorance and incorrect or delayed diagnoses, which caused distress and feelings of helplessness and frustration that significantly influence the implementation of a proper scientifically based treatment plan for the child [20].

Within the health sector, it was stated that upon receiving the diagnosis, families were faced with a new set of challenges. The majority of the parents experienced challenges and difficulties in navigating the system [50]. These challenges entailed receiving ineffective and unclear communication from health professionals [46, 47, 50, 52]. Lack of resources and proper support from the system placed families under extra financial strain where they had to pay out of their own pocket for services or drive long distances to access treatment facilities. It is interesting to note that the analysed articles make special mention of the significant distress fathers experience due to financial uncertainties, problems, and difficulties [46]. It is also indicated that this experienced incompetence of the health sector resulted in caretakers and families doubting the competence, expertise, and commitment of the health professionals they had to trust with the treatment of their children [46, 48, 52, 50].

Within the education sector, parents indicated their concerns regarding their child’s future and proper school and educational facilities, resources, and support. Additionally, the availability of and access to a school that caters for children with autism is especially concerning [52]. It was also indicated that the limited understanding of autism by teachers in schools made it difficult to resolve behavioural issues that originate from the disorder. This often results in conflict between teachers and parents where the family’s parenting style is judged because of the teacher’s own ignorance [47].

The analysed articles emphasised that the lack of support services families are faced with during pre-diagnosis has a significant impact on making a proper diagnosis and thus has a ripple effect on the treatment and efficient management of the child. Families are left frustrated and helpless, feeling alone in their fight to help and support their children. Post-diagnosis, the lack of proper and scientifically based support within the health and educational sectors puts an extra burden on especially families from lower socio-economic groups. This also results in families distrusting the competence and commitment of support workers within the health and education sectors, leaving these families to feel alone, isolated, and rejected by society, which forces them to do everything by themselves.

6.2.2. Theme 6: Social Awareness

Social psychology theory states that if something is different, not conforming, and you do not have knowledge or understanding of why it is different, society will judge and reject it [54]. These experiences of being rejected, stigmatised, isolated, and judged are on a daily basis in the foreground of what families that raise an autistic child experience. The lack of knowledge and social awareness of not only the broader community and society but also of even extended family members has a significant influence on the social functioning of these affected families [48].

Pre-diagnosis, families indicated that they experienced stigmatisation and prejudice from society, as well as family members, pertaining to their child’s behaviour [20]. Prejudices experienced by parents were mainly informed by incorrect conceptions of normal development, as well as different cultural beliefs regarding the aetiology of a child’s behaviour, which resulted in parents becoming exhausted and vulnerable to societal judgment [51]. Thus, not only is their child judged but also the parents’ parenting style and relationship with their child. It is further noted that even when the family makes an effort to navigate their way in obtaining an understanding of their child, they are faced with further judgement from family, society, and professionals, including statements on their ‘lack of awareness of their child’s behaviour at an early stage’ and ‘how their ignorance caused their child severe distress’ [20, 49]. Some of these isolating and marginalising experiences include incompetent and unsupportive professionals not providing the appropriate resources and support needed. In these instances, the families experienced that the professionals compensated for their incompetence by judging the parents’ parenting style and self-developed attempts to understand and help their child [44, 48, 47]. Families expressed that constantly having to fight the system and the stigma that accompanies autism made them experience a sense of helplessness as they are constantly labelled and marginalised [48].

Upon receiving the diagnosis, families expressed that they endeavour on the route with extended family members and communities not to judge and label but to rather attempt to gain knowledge and understanding [49, 51]. Raising awareness and advocating for people with autism become the responsibility of the affected families on their own, with little support and help from the system and the government [45, 47, 49, 51, 52].

Lack of social awareness regarding autism results in families constantly being judged and stigmatised, not only by the community but also by extended family members [52]. To take your child with you to the shop or to a social gathering always poses a risk of ending in disaster and you as well as your child being judged and labelled [46]. A lack of social awareness, empathy, and acceptance leads to these families living a life where they find safety and acceptance only when they isolate themselves from the eyes and tongues of society. Parents reported experiencing stigma and blame, which appeared linked to cultural beliefs and impacted the support families received, leading to social isolation [51]. Furthermore, a sense of self-blame was reported by parents for their child’s behaviour, as they felt they caused or had an influence on the child’s behaviour, such as causing problems with family [48]. As it would result in parents experiencing psychological problems as explained above.

6.3. Psychosocial Coping Strategies

With the abovementioned experiences in mind, it is clear that families that raise an autistic child experience a different dimension and level of parenting stress. People respond to stress with different coping strategies [55-57]. It was interesting to note that in the analysis of the identified studies, the integration of the psychosocial experiences of these families naturally leads to the identification of certain psychosocial coping strategies that these families developed and used to survive the day in and day out. Both mothers and fathers reported that if they could manage to decrease their parental stress, they would be able to experience and report positive experiences and interactions not only with their autistic child but also with their other children [20, 45, 49, 50]. The four main coping strategies identified are isolation, information seeking, meaning-making, and the establishment of a support system.

6.3.1. Theme 7: Isolation

In the first subtheme, parents indicated that they found that pre-diagnosis and before the implementation of an applicable intervention strategy, they used isolation from social settings to protect their child and to decrease their own parental stress. Parents expressed that isolation is, however, a consequence of having to invest time and energy in supporting their children [20, 46]. Parents, therefore, opted to stay in familiar surroundings where routines could be maintained. In a study [58], one parent expressed that ‘people tend to be ignorant and if you listen to them and what they say, so we tend to be closed off now, me and the wife don’t really mix with anybody’. The analysed studies indicated that due to a lack of awareness of autism and what it entails, they experienced people as rude, unsympathetic, and judgmental about their child’s behaviour [48]. The families indicated that they resorted to isolation; describing it as a consequence of having to invest time and energy in supporting their child and that they did not have the energy to also attempt to manage society’s perceptions and judgements. They indicated that they found that with isolation it was possible to protect their child and manage the child’s behaviour by choosing familiar and predictable surroundings where routine can be maintained [48, 49].

6.3.2. Theme 8: Information Seeking

In this second subtheme, the families used information seeking and the gathering of relevant and scientific information to empower themselves. In one of the studies conducted [20], several parents indicated that they took formal courses on autism in order to understand more about the diagnosis and to learn how to work with their child at home, other families join support groups to learn more. This assisted families in maintaining some sense of control over the diagnosis, protecting them from feeling helpless and increasing their feeling of self-efficacy [49, 52]. It also increased the families’ sense of resilience. One parent [48] confirmed this by stating: ‘It is not as bad as all that and once you know about it and you can learn to deal with it, it is not a death sentence.’

6.3.3. Theme 9: Meaning-making

The third subtheme, namely, to create meaning, is closely related to the second subtheme of seeking information. It was interesting to note that one of the most powerful benefits of more information and knowledge was the fact that it empowered and assisted parents and families in developing a greater appreciation of the smaller milestones performed by their autistic child. The knowledge helped them to understand how much bravery and effort small daily tasks and accomplishments took from their child and assisted them in preserving and developing a sense of hope. The families indicated that seeing and being aware of the small changes and milestones in their autistic child’s behaviour guided them to a new view of what life and success are about and actually finding meaning in a new viewpoint of their child’s diagnosis [52].

6.3.4. Theme 10: Support System

The fourth psychosocial coping mechanism identified was the establishment of a safe and understanding support system. The identified studies showed that families that raise an autistic child found it valuable to engage with other families that raise an autistic child. It is indicated that they found psychosocial support in exchanging information and discussing a range of issues and shared concerns and challenges. Some of the main topics where their common experiences were especially valuable were topics such as learning how to navigate the system (health and education), as well as guidelines and recommendations for interacting with various professionals [48]. The families experienced this support as an opportunity to share problems and provide one another with emotional and practical support not understood by typical families and well-equipped professionals. This instilled a sense of confidence in families about their parenting, providing a sense of ‘relief and hope’, and above all forming connections and making friends [20, 50, 52].

Some of the families indicated that they also received support from their close family members, such as spouses [20, 46, 50, 52]. This made them feel that they were not alone and helped them to feel comfortable to reach out and support those around them [51]. Their family’s support and acceptance helped the families to make time for themselves as they could engage in recreational activities such as writing poetry, exercising, art, and embracing the concept of ‘me time’ when they knew there was somebody who would look after their autistic child [48].

7. DISCUSSION

The objective of this article was to explore the pre- and post-diagnosis psychosocial experiences of families that raise an autistic child. The analysis and synthesis of the identified articles indicated that the identified psychosocial experiences of the families that raise an autistic child were multidimensional and fit well within a contextual and systemic perspective. It was interesting to note in the results how the various contextual systems (individual, micro-, meso-, exco-, and macrosystem) interactively influence one another and play an integral role in the psychosocial experiences of not only the autistic individual but also the family and caretakers as part of the microsystem. The integral role that families play in raising an autistic child is increasingly acknowledged and confirmed. The family is the primary support system for these children and the responsibility in this regard stretches over a lifespan. It is clear that the psychosocial wellbeing and quality of life of these families, together with the contextual systems involved, are increasingly becoming the focus of research attention [30]. The family quality of life (FQOL) framework had its origin [57] in this focus.

The FQOL framework provides a positive approach that seeks to improve the quality of life of families that raise a child with a disability. FQOL focuses on the “goodness of life” or the ‘conditions where the family’s needs are met, and family members enjoy their life together as a family and have the chance to do things which are important to them’ [58]. It is a multidimensional framework measured by indicators common to all families that make provision for both internal dynamics (cohesive family interactions), as well as external support, resources, and dynamics [30]. This framework is a virtuous fit for the integration and synthesis of this study’s results as it underlines this study’s argument that a better understanding of a family’s psychosocial functioning and experiences is important for the effective management of not only the affected individual but the family system as a whole as well. The outcome of the FQOL approach is that proactively supporting families with children with disabilities can build the capacity and skills for them to deal with challenges and adversities. It is further indicated that a family that is living an optimal and quality life within their home and community will be able to contribute to the ongoing stability of society as a whole [58-60]. This framework pays attention to a family’s quality of life by focusing on the following four concepts: (1) individual family member concepts, (2) family unit concepts, (3) performance concepts, and (4) systemic concepts.

The FQOL framework proposes that these four concepts interact with one another and that singly or in combination these concepts predict a family’s quality of life, which can be used to identify the family’s strengths, needs, and priorities to focus on. The first FQOL concept is the individual family member, which refers to aspects of the involved individual family members’ demographics, characteristics, experiences, and beliefs [59].

In the analysis and synthesis of the identified studies, the main individual family member concepts that influenced the families’ quality of life were the various emotions experienced by the parents and involved caregivers, with a specific focus on the grief process and the experience of loss. It was interesting to note how the individual emotions experienced by families differed pre- and post-diagnosis. Pre-diagnosis, the uncertainty about what is going on and the helplessness accompanying the uncertainty were prominent. Post-diagnosis, feelings of guilt, self-blame, and sadness were prominent. The theme of loss was especially prominent as the families verbalised that they had an intense feeling that they had lost their ‘healthy, ideal child’ and all their dreams and hopes for him/her. Other identified individual family member concepts that influenced the family’s quality of life were the changes parents had to make in their parenting styles and how the child with autism affected the individual members’ experiences of family cohesion, family role changes, and the lack of time spent together as a family. It is clear that on an individual family member level, the challenges and adversities that affect the individual family members’ psychosocial wellbeing and quality of life are vast and intense. To balance these challenges, it is interesting to take note of the psychosocial coping mechanisms the families mentioned that helped them to cope and to strive towards a better quality of life. The main coping mechanism mentioned on an individual level was how they used isolation to protect their autistic child and themselves. It was also interesting to note how the gathering and seeking of information to improve their understanding and skills empowered these families. Their quality of life was enhanced by being able to focus on small milestones and finding new meaning in what life and success are about.

The second concept is the family unit concept, which is the collective number of individuals who consider themselves to be part of a family and who engage in some form of family activities together on a regular basis [59]. The reviewed studies indicated that a higher level of family distress was experienced pre-diagnosis as families had to adapt and venture on unfamiliar terrain in attempting to deal with unpredictable and uncontrollable behaviour that impacted the whole family’s functioning. The analysed studies indicated that this family distress resulted in over-vigilant parents attempting to monitor every move of the child [20, 44, 47, 49]. This, however, negatively affects the family dynamics as a great deal of attention and care are given to the child and less to other members of the family [44, 48, 51, 52]. Family resources and support are channelled to the child with the aim of protecting and understanding; however, it negatively impacts sibling and marital relations [44, 49, 50]. Research [21, 30, 31, 33] indicates that in the early developmental years of a child’s life, the family is typically the primary environmental influence on a child, and this includes sibling relations. Studies [16, 19, 23, 27] further indicate that having a sibling with a developmental disorder can leave other children with feelings of confusion, isolation, and frustration. This also affects the parents as they are more prone to serious mental health problems and an overall decrease in wellbeing and physical health [12, 21].

The family’s social life is affected in this regard due to a lack of awareness and knowledge pertaining to autism among the general public, which often results in families constantly being judged [48, 44, 48, 52]. Some parts of society ascribe the child’s behaviour to external supernatural forces, meaning that they believe that the child’s symptoms and behaviour are punishment from the ancestors or from God [33, 34, 36, 50]. With the aim of avoiding societal judgement, families, therefore, tend to isolate themselves from societal gatherings and start obtaining information with the aim of understanding their child [52]. Studies [48, 51] further indicate that it is common for parents of children with autism to suffer from feelings of isolation and exhaustion due to society’s lack of understanding and the stigmatisation of their child’s behaviour. Families are therefore forced to give up their social lives, vacations, and personal dreams as their attention shifts to assisting their child and gaining a better understanding of the child’s behaviour [12]. Regardless of the above, when families receive the diagnosis, there often seems to be a positive effect on those affected [49] as the diagnosis offers a sense of relief. Due to families having a certain level of understanding and acceptance of the child’s situation, [20, 52, 48] receiving the diagnosis strengthens relationships, especially with their spouses. They start working together, which is emotionally rewarding and increases their emotional bond with their spouse, which results in the improvement of their parenting style and family dynamics [50-52]. In the analysed studies, it was interesting to note how the families’ quality of life was enhanced by building new support systems with other families with children with autism. The shared challenges and experiences gave a sense of belonging and acceptance that helped to enhance the general psychosocial wellbeing and quality of life of families that are raising an autistic child.

The third concept is the performance concepts, namely the formal services, support structures, and practices developed and offered to individuals with disabilities and their families [59]. Services are a range of educational, social, and health-related activities expected to improve the outcomes for the individual or the family as a whole (counselling, medical/dental care, or therapies such as speech-language therapy). The reviewed studies indicated that the lack of resources and proper support from the system resulted in families driving long distances to access treatment facilities. Furthermore, families were faced with incompetence within the health sector, as some children were misdiagnosed, referred from one place to another without any answers, and ill-treated by professionals. This resulted in caretakers and families doubting the competence, expertise, and commitment of the health professionals they had to trust with the treatment of their children [48, 52, 50]. The analysed studies indicated that they experienced that they had to ‘fight’ the system every step of the way, which had a definite impact on the psychosocial wellbeing and the quality of life of the family. This ‘not helping’ and ‘not understanding’ the families experienced from the indicated support services made them feel alone and scared. It seems that families compensated for these feelings by equipping themselves with information on the disorder, raising awareness among communities and family members, and relying on reliable social support from friends and family members who assisted them in making meaning of the diagnosis.

Lastly, the systemic concepts entail a collection of interrelated networks organised to meet the various needs of society, such as healthcare, education, and legal systems (e.g. healthcare systems and policies) [59]. On a systemic level, it was clear that families experienced the available structures and policies within the health and educational sectors as lacking. Pre-diagnosis studies indicated that the lack of social support services, as well as proper knowledge and structures within the health sector, affect the ability to obtain a proper diagnosis. This has a detrimental effect on the effective treatment of the child as a proper diagnosis is needed to guide proper and effective treatment. Upon receiving the diagnosis, families are faced with financial constraints as they must cater for the child’s treatment, knowing that it is a lifelong commitment. Few schools and educational facilities make provisions for children with autism. Those that do make provisions cost a lot of money, which leaves many families with nowhere to go to educate their children and develop their skills and abilities [61, 62]. On a societal level, these families are faced with stigmatisation and judgement on a daily basis. Society is not open to anything that is different from what they consider to be normal. They attempt to make it fit in by criticising and judging the parents’ parenting style, as well as the cultural compliance of parents with certain beliefs and traditions. General lack of social awareness results in families feeling isolated and unwelcome in society due to their child’s behaviour.

The FQOL framework indicates that these four concepts interact individually and in combination with one another to give an indication and a prediction of a family’s possible quality of life and thus psychosocial well-being. With the above mentioned in mind, it is clear that families that raise an autistic child experience challenges on all four of these levels. To address the psychosocial well-being of these families and to enhance their quality of life, it is important to pay attention to the specific challenges, needs, and opportunities on all four of these conceptual levels [59].

Although South Africa is known for good policies and legislative frameworks, the implementation and operationalisation of these policies and visions prove to be a dilemma. Although some of these policies with regard to support to families with children with disabilities have been implemented, the large number of people who need to be helped by the few service points and healthcare workers available results in many families still needing assistance. Research [62] furthermore indicates that children with mild to moderate disabilities are still being excluded from the grant service. In many instances, this means that children with autism are excluded from the grant service, which creates a huge financial burden for the parents. A study [30] conducted by Schlebusch, Dada, and Samuels in South Africa, which used the FQOL framework, found that families who received proper disability-related services were mostly satisfied with their family’s quality of life, as they were receiving support. This suggests that families that do not receive or who are on the waiting list for support are likely to feel so overwhelmed and defeated that it influences their overall quality of life.

Research confirms that raising an autistic child provides intense and unique challenges that put the involved families under severe psychosocial stress. The analysis of the identified studies indicated that in dealing with this stress, families developed certain psychosocial coping mechanisms to help them cope with difficult circumstances. These coping mechanisms include using isolation to protect their child and themselves, seeking information, finding meaning in the diagnosis, and establishing an understanding, accepting, and reliable support system.

In summary, the psychosocial experiences synthesised from the identified studies indicate that the main psychological experiences of families that raise an autistic child are a variety of emotional responses, a feeling of grief and loss, parenting challenges, and changes in the family dynamics and cohesion. On a social level, the main experiences reported were the lack of support services and how the lack of social awareness leads to the burden of stigmatisation and uninformed prejudice. Families used psychosocial coping mechanisms such as isolation, seeking information, meaning-making, and the establishment of a support system to lower their parental stress and open themselves up for experiencing positive moments.

It can be concluded that autism is becoming more prevalent both internationally and in South Africa [1]. Research is clear on the fact that the family that raises an autistic child plays an integral part in the effective treatment and management of the child’s life and future. The identified and analysed studies indicated that the psychosocial experiences of the involved families are unique and challenging. To optimise these families’ quality of life, it is important to pay attention to the various FQOL concepts and to attempt to minimise the experienced adversities and to optimise the moments of well-being and meaning in each of these conceptual fields. Evidence-based, concise intervention programmes, based on the psychosocial experiences of families that raise an autistic child, are of the utmost importance in enhancing these families’ quality of life. On an individual concept level, it is important to pay attention to the pre-and post-diagnosis emotional experiences of the affected families. Proper support and proactive counselling are important to assist with the helplessness before the diagnosis and the feeling of loss after the diagnosis. It is also important to facilitate the changes that are expected in parenting styles, family cohesion, and time spent together. In terms of the family unit concepts, the establishment of proper social support services and support groups for families and people who share the experience of the challenges of raising an autistic child will be valuable. The deliberate implementation of social awareness programmes to protect families from stigmatisation and being judged will enhance the quality of life on the family unit level. In terms of the performance concepts level, there must be clear communication and concise and consistent structure and lines of reporting and managing children with autism. Proper training and sensitising of the healthcare workers who are the first point of referral will make a huge contribution to the quality of life of these families. Lastly, in terms of the systemic concepts level, the evaluation of policies that are not implemented and utilised optimally will aid in ensuring that what we have is documented on paper and also what is happening on the ground level. The need for proper and easily accessible educational facilities and support systems could be highlighted as a crisis for families that raise an autistic child.

Therefore, through using the FQOL framework for families that raise an autistic child, practitioners will be provided with ways to think about and work towards what brings fulfilment and joy to the families they serve through viewing the parent/caregiver as the ‘expert’; during which time supportive resources must be made available in order to enable them to build their knowledge and understanding of the specific needs for children with autism. Furthermore, societal awareness and sensitivity need to be created if an autistic child is to be accepted and supported by society, and so that integration into society for families and autistic children will not be difficult.

8. LIMITATIONS

The study limitations are based on the characteristics of design or methodology that impacted or influenced the interpretation of the findings from the research. Due to the research not involving participants, made it a no-risk study; however, limitations were still encountered.

The researcher initially wanted to conduct a qualitative study with mothers who raise autistic children; however, the recruitment of participants posed difficulties, as they are a vulnerable targeted group. Gaining ethical clearance from the community gatekeeper was therefore a problem. This resulted in the researcher and study leader re-discussing the study and deciding to conduct a rapid review instead. Some of the challenges that were present with the rapid review were as follows:

- A lack of studies that explored this specific topic/phenomenon, as most of the available literature and research focused on the pathology of autism and covered topics such as the development and increase in the prevalence of autism.

- Upon conducting the literature search and identifying studies that were applicable, the challenges identified were the age and level of functioning among children with autism as these differed. This meant that families’ experiences would be different as children grew up and families learned to adjust. The researcher and reviewer, therefore, had to ensure that the age range within all studies was between five and 18 years.

- This research was a small-scale study and was conducted within the limited scope of a master’s mini-dissertation. Furthermore, during the keyword search, it was important to identify studies that were in conjunction with the keywords searched for the studies. However, this resulted in most studies being excluded as they explored different phenomena together with the experiences of families and therefore did not answer the research question.

- This study focused on families. It is not known how parents as part of the family are affected. It is not known how siblings as part of the family are affected.

- Three of the studies explored fathers’ experiences of raising an autistic child. This might have an effect on the results as the experiences would be subjective and not encompass families’ experiences. However, when comparing the experiences, similarities and differences were noted. Furthermore, the research question aimed to explore families, parents, mothers, fathers, guardians, and caregivers.

- The search string only produced studies published between 2000 and 2019. The results of the search were limited in their scope and inclusivity regarding the representation of other elements in the research about families and autism. For example, South Africa has eleven official languages, and each offers a different cultural perspective which, partly, informs the understanding of children living with autism.

- The review focused more on cases of religious negative coping. This is a limit because there are positive coping effects of religious beliefs and practices researched from different settings worldwide. Therefore, we recommend that future systematic reviews look at intervention strategies and studies focus on both the negative and positive effects of religion in a South African context. This will be a guide for families raising a child living with autism.

CONCLUSION

The psychosocial themes identified in the analyses and synthesis of the identified articles fit in the conceptual fields of the FQOL framework, namely individual concepts, family unit concepts, procedural concepts, and systemic concepts. A deeper and better understanding of the psychosocial experiences of families that raise an autistic child within these various concepts is essential in informing scientifically sound intervention and support programmes. Therefore, a deeper and better understanding of the psychosocial experiences of families that raise an autistic child within these various concepts is essential for informing scientifically sound interventions and support programmes. The aim of these programmes and interventions should be to activate and sensitise the whole system involved so that families that raise a child with autism can experience satisfaction, joy, and quality family life. In addition, they need to be ensured of reliable, competent, and supportive professional and personal support networks that work together to raise societal awareness and sensitivity towards children with autism and especially their families.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

B.K.P. and H.K.C. wrote and partly analysed the findings of the study. W.F.T. and P.E revised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| FQOL | = Family quality of life |

| ASD | = Autism spectrum disorder |

| EDS | = EBSCO Discovery Service |

| COMPRES | = Community Psychological Research |

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines and methodology were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST