All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Intimate Partner Violence among Married Couples in India: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Introduction:

Intimate partner violence (IPV) among married couples is an area of concern in the current scenario in India. It is an important public health issue that substantially affects a person’s mental and physical health. Thus, in this systematic review, we aim to review and analyze the previous literature on the antecedents, consequences, and intervention studies on IPV conducted in India.

Methods:

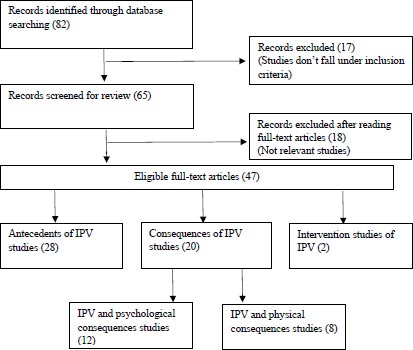

We conducted a literature search on the following network databases: APA PsycNet, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect. We selected 47 studies potentially relevant articles published from 2000 to 2023 for detailed evaluation. The systematic review was done adhering to PRISMA guidelines.

Results:

Our results indicated that very few studies are conducted in the Indian cultural context that explored the issues of IPV. There are various demographic, cultural, and individual factors acting as risk factors for perpetrating IPV in India. Studies also show a significant impact of IPV on mental and physical health. Additionally, very few interventional studies have been conducted to prevent or reduce IPV in India. From the study results, we can infer that there is a need to adapt or develop indigenous interventions for IPV in India.

Conclusion:

Considering the aspects discussed in the present study, we understood that IPV is a major, widely prevalent, under-recognized issue in India. So, the study implies a necessity for conducting more research in the Indian cultural context and developing indigenous intervention studies in India.

1. INTRODUCTION

“Any behavior within an intimate relationship ( e.g., married couples) that causes physical, psychological, and sexual harm to those in the relationship” is termed Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) [ 1]. It is also a significant public health issue that substantially impacts both men’s and women’s mental and physical health [ 2, 3]. Globally, one in three women faces IPV at least once in their lifetime [ 1]. In most cases, women are considered the victims of violence [ 2] and males as perpetrators [ 4, 5], although few studies have shown that men can also be IPV victims [ 6].

A rich literature is available on IPV and its correlates in the Western cultural context. However, very few studies have been carried out to explore the antecedents and consequences of IPV in the Indian cultural context. IPV is now a concern in India because a growing number of males [ 7] and females [ 8] report IPV in their relationships. So, the main goal of this paper is to present a systematic review of studies conducted in India over the past decades exploring the antecedents and consequences of IPV among married couples and interventions to prevent and reduce IPV in India.

1.1. Prevalence Estimates of IPV in India

Globally, approximately one-third of women are experiencing IPV [ 1]. India has a high violence perpetration rate against women [ 8]. Similar to the results of WHO (2013), the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) conducted in India also reported that one in three women had experienced IPV in their lifetime [ 9]. NFHS reported that nine in ten women never reported violence against them. Thus, it is clear that IPV is a vastly under-reported issue in India. Contrary to common belief, more men are receiving various psychological and physical abuse and harassment by women [ 7]. More than half of the men receive spousal violence against them [ 10]. Hence, identifying male victims is difficult in a country like India since most men might not be ready to report their issues [ 11]. For ages, India has been a male-dominant society, so it is hard to believe that females are perpetrators and males are IPV victims [ 12]. Straus (2005) argued that most IPV is bidirectional [ 13]; both men and women are potential victims and perpetrators of IPV [ 14]. However, IPV against men is less recognized by society than IPV against women [ 15].

1.1.1. Prevalence of IPV among Women

WHO (2012) reported that about 60% of people in an intimate relationship had experienced physical violence, and about 75% experienced emotional abuse from their partners in their lifetime [ 16]. Our review shows that in India, one in three Indian women have IPV experience [ 16]. Physical violence is most common among IPV, followed by emotional or psychological violence and sexual violence, especially in women [ 16, 17]. In contrast, some other studies show that psychological violence is most common among IPV [ 18], followed by physical violence and sexual violence among women [ 19]. Usually, the perpetrator would be the woman’s husband or intimate partner (15%) or a person in a position of authority in their community (10%) [ 20]. Gundappa and Rathod (2012) argued that the deep-rooted patriarchal system, cultural acceptance of violence against women, and treating women as subordinates of men in Indian society [ 21]. These might be the reasons for IPV against women in India.

1.1.2. Prevalence of IPV among Men

IPV is always discussed concerning women. Men are always considered the perpetrators. In a study, Deshpande (2019) stated that due to stereotyped gender roles, society hardly believes that women can inflict violence against men [ 22]. In India, the old traditional family structure was the joint family system [ 23]. It was patriarchal; the status of the women in the family was very low [ 24], members of the family had no individuality, and the eldest member, especially males, of the family made decisions for the family [ 25]. However, in current eras, societal values, culture, and norms changed greatly due to modernization and Westernization in India. Nowadays, both men and women work equally, raising and managing households. These drastic socioeconomic changes affect the family structure, and men are also being victims of IPV [ 22]. A study conducted by Malik and Nadda (2019) found that 52.4% of men in India were victimized by gender-based violence [ 10]. Among them, 51.5% of men experienced violence from their wives/intimate partners at least once in their lifetime. Similarly, Deshpande (2019) argued that men face several verbal, physical, emotional, psychological, and sexual abuses [ 22]. The most common spousal violence against men is emotional violence (51.6%), followed by physical violence (6%), then sexual violence (0.4%) by any female. Criticizing (85%) is the most common form of emotional violence, followed by insulting in front of others (29.7%) and then threatening or hurting (3.5%). Slapping is the most common physical violence, and beating by a weapon is the least common. Physically forcing a partner to perform any sexual act and do sexual intercourse is some sexual violence against men [ 10], which is quite limited compared to other forms of IPV. Similarly, other studies also corroborated the same results in the case of men [ 26]. In a review article, Deshpande (2019) stated that the law in Indian society mainly supports women victims [ 22]. Moreover, men are not ready to report their issues [ 27]. They are silent victims of these kinds of abuse because many men are ashamed of talking about their experiences of abuse/violence by their wives [ 28].

1.1.3. Prevalence across Regions

According to studies, the prevalence of IPV varies by region in India. In the northern region of India, husbands revealed that they perpetrated one or more episodes of physical violence (25.1%) or sexual violence (30.1%) against their partners [ 29]. Whereas in Southern India, one-third of women reported having physical violence (hitting), forced sex, or both by their partners [ 4]. This prevalence rate is similar to the results of NFHS-4 [ 9]. Furthermore, in Eastern India, the prevalence of IPV of physical violence is the least common (16%-22%), with one in two women experiencing psychological violence (52%-59%) and one in four women being victims of sexual violence (17%-25%). Any form of violence among women was 56%- 59.5% [ 19]. Studies on IPV among men are scarce. However, a study by Malik and Nadda reported that more than half of men (51.5%) in Haryana are victims of gender-based violence/domestic violence from their intimate partners [ 10].

1.2. Culture and IPV in Indian Society

Within certain cultural or social groups, there may be some rules or expectations of an individual’s behavior, i.e., called cultural and social norms. These are also responsible for shaping an individual’s behavior, including the use of violence [ 30]. Some cultures use violence as a conflict-resolving method [ 13, 31]. Such cultural acceptance of violence is a risk factor for interpersonal violence. Previously, IPV was only regarded as a personal matter between two individuals, but now it is acknowledged as a complex sociocultural problem and public health epidemic [ 32].

India has been a collectivistic and patriarchal society for decades, which promotes social cohesion and interdependence among people [ 33]. These societal and cultural backgrounds often influence family dynamics. Along with that, this ideology of the collectivist cultural system promotes patriarchy. Patriarchy plays a role in violence [ 34]. Violence is used as a tactic to resolve conflict among Indian families [ 18, 31]. Go et al. (2003) argued that in India, men are entitled to use violence to correct and discipline women’s behavior [ 35]. In some cultures, IPV existed as an acceptable social norm and behavior for centuries and was even legally sanctioned [ 32]. This kind of patriarchal mindset in Indian society thinks that man is socially superior and has the right to exert power over women. Which correspondingly leads to IPV among married couples. Most of the time, women who depend on their husbands for money, material assets, and expenditures usually get abused by their partners [ 18].

1.3. Goal of the Review

Although the previous literature affirms that the prevalence of IPV is high in India, the number of studies is very few. India has undergone a drastic social change in recent decades due to globalization and modernization. These drastic socioeconomic changes developed work-family conflict and increased divorce rates. The literature shows that most studies focus on female IPV victims, while research on male victims is rare. Additionally, IPV studies in India are sporadic and narrowly focused ( e.g., domestic violence). Along with that, in some studies, the term domestic violence is used instead of IPV. Domestic violence is a broad term that includes IPV but is not limited to IPV. It involves violence against or among any members of a family. So here we are, distinguishing IPV from domestic violence. Thus, the present review focuses on the antecedents and consequences of IPV among married couples in India. In addition, we reviewed studies that report IPV on Men in the Indian context. We also examined studies that focus on interventions to mitigate IPV.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Objective

1. To review the previous literature and examine the antecedents and consequences of IPV in India.

2. To review and examine the relevance of developing an intervention for reducing IPV in India.

2.2. Search Strategy

A literature search was conducted on databases such as APA PsycNet, Google Scholar, and ScienceDirect, which searched for potentially relevant articles from 2000 to 2023. Eighty-two records were identified through database search. For all the databases, keywords such as ‘Intimate partner violence in India,’ IPV in India, ‘Partner violence in India,’ ‘domestic violence in India,’ and ‘antecedents and consequences of IPV’ were used to search articles. Relevant articles were retrieved for more detailed evaluation.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We found eighty-two studies in the first search. Of them, forty-seven articles were included and examined in this review based on the study objective and after the screening process (Fig. 1). Among the forty-seven research articles (one study included in all three subcategories (Antecedents and, psychological and physical consequences of IPV studies) of IPV studies and two study included in two subcategories of IPV studies (antecedents and psychological consequences of IPV studies), twenty-eight were studies on antecedents of IPV, twelve were studies on psychological consequences of IPV, eight were studies on physical consequences of IPV, and two were intervention studies on IPV.

3.1. Literature addressing Antecedents of IPV in India

Table 1 in the appendix shows studies on antecedents of IPV in India. For victims of IPV, being hurt by a spouse or intimate partner may be an extremely traumatic experience. Different cultural factors (holding particular tenets regarding dominance and hierarchy or gender ideologies), sociodemographic factors, and psychological factors (personality disorders, the experience of any childhood trauma, and witnessing IPV as a child) contribute to IPV [ 8, 36]. In some situations, an individual’s own level of behavioral well-being can also cause IPV [ 37]. Combinations of all these factors can also play a role in the development of IPV.

| Author & Year | Method | Sample | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sinha et al. (2022) | Quantitative | N= 50,848

Age:15-24 |

• Adverse childhood experiences are associated with IPV perpetration. |

| Murugan et al. (2021) | Quantitative | Data retrieved from NFHS-4

N= 45,211 Age: 15-49 |

• Women’s empowerment contributes to past-year and lifetime IPV victimization risk among Indian women.

• Women who had a higher education, property, and decision-making power in their homes are less probable to experience IPV. |

| Weitzman. (2020) | Quantitative | Data retrieved from NFHS-

N=57550 Age: 18-49 |

• Gender of a first-born child is a risk factor for IPV. Women with first-born child is a female report IPV more than women with first-born male children.

• The higher prevalence of sexual violence found among mothers with no education. |

| Thomas et al. (2019) | Quantitative | N= 1600 men (959 urban and 641 rural)

Age:18- 50 |

• Deeply rooted patriarchal attitudes internalized within men, childhood gender inequity, and experiences of violence among men emerged as a set of risk factors for perpetrating violent behaviour towards women. |

| Raj et al. (2018) | Quantitative | N=853 Women

Age: 18-30 |

• Income generation capacity and having one’s own money never predicted IPV among women. |

| Dasgupta et al. (2018) | Quantitative | N= 1081

Age: 18-30 |

• Among married people, nearly one-fifth of wives conveyed an experience history of physical and/or sexual IPV.

• Husbands with better gender equality ideologies are associated with lower IPV among their partners. • IPV and alcohol use are related. |

| Patra et al. (2018) | Literature review | --- | • Culture, economic status, law, politics, and Personal factors have a role in IPV. |

| Kalokhe et al. (2017) | Meta-analysis | 137 quantitative studies | • 4 in 10 Indian women reported that they suffered domestic violence or other forms of abuse in their lifetime.

• Income, education, unemployment, nuclear family, caste and religion, witnessing of violence, childhood abuse, extramarital relationships, age at marriage, marital duration, dowry, type of marriage, male child preferences, acceptance of DV, women’s status and social support, and alcohol and drug use are the main risk factors of DV in India. |

| Rashada & Sharaf (2016) | Quantitative | Secondary data (retrieved from NFHS-3)

N= 124385 Age: 15- 49 |

• Income inequality and IPV are related.

• Higher qualifications, employment, being from a non-scheduled caste, and better financial status acting as a protective factor from IPV. |

| Fleming et al. (2015) | Survey | 7806 | • Witnessing parental violence, permissive attitudes towards violence against women, having inequitable gender attitudes, and older age were associated with the perpetration of physical violence against women. |

| Begum et al. (2015) | Survey | 1137 | • Early marriage, employment status, justified attitude toward wife beating, and spouse’s drinking behavior are associated with domestic violence. |

| Jin et al. (2014) | Quantitative | N=134 men

Age: 24 -74 |

• Perceived marital power, early exposure to violence, drinking habits, depression, and marital satisfaction are associated with IPV. |

| Kamimura et al. (2014) | Survey | 219 | • Cultural normalization of abuse, gender role expectations, need to protect family honor, and arranged marriage system are some of the risk factors for IPV. |

| Mishra et al. (2014) | Quantitative | 144 | • Alcoholism and literacy status are related to the perpetration of IPV. Among them alcoholism is the most important factor.

• Majority of the abused women were dependent on their husbands for money, material assets and expenditure. |

| Priya et al. (2014) | Quantitative | N=1,650 men and 550 women.

Age: 18-49 |

• Controlling behavior of men, gender inequitable attitudes, and men’s preference for sons over daughters, are associated with an increased tendency to perpetrate violence toward their partners.

• Higher education of men lowers the perpetration of IPV. |

| Sabri et al. (2014) | Survey | 67226 | • Low or no education, lower socioeconomic status, living in rural areas, and having more children, are risk factors for severe physical IPV.

• Spouse’s alcohol use, jealousy, suspicion, controlling behavior, and emotionally and sexually abusive behaviors related to an increased chance of women being victimized by severe IPV and injuries. • Exposure to domestic violence in childhood and adherence to social norms that accept husband’s violence are some other risk factors for perpetration of IPV. |

| Subodh et al. (2014) | Interview | 267 | • Higher age of husband, lower education and unemployment of either of the spouse, lower financial staus of the family, and nuclear family structure are related to IPV. |

| Babu & Kar (2009) | Survey | 3433 | • Socioeconomic characteristics of women are significantly related to IPV victimization. |

| Ackerson et al. (2008) | Survey | 83627 | • Increasing women’s levels of education is key to decreasing IPV victimization among women. |

| Ackerson & Subramanian (2008) | Quantitative | Secondary data (retrieved from INFHS)

N= 83,627 Age: 15- 49 |

• Women who are uneducated, from marginalized castes, and living in poor households have a higher likelihood of reporting IPV than those living in more privileged conditions.

• Women from scheduled tribes and other backward classes did not report elevated rates of IPV. While women in scheduled castes reported more IPV victimization. • Gender inequality is negatively related to IPV. |

| Varma et al. (2007). | Structured Interview | N=203 | • Alcohol use is a risk factor for IPV. It increases the severity of violence. |

| Jeyaseelan et al. (2007) | Survey | N=9938

Age: 15–49 |

• Spouse’s daily consumption of alcohol is related to dowry harassment among women.

• Those husbands reported that they have witnessed their mothers being harassed by their fathers and they have experienced harsh punishment in their childhood. Witnessing and experiencing violence in childhood develop future IPV perpetration. • Good social support and higher socioeconomic status are protective factors for IPV. |

| Koenig et al. (2006) | Survey | 4520 | • Individual-level factors such as childlessness, financial pressure, and intergenerational transmission of violence are risk factors for IPV/domestic violence.

• Community-level norms concerning wife-beating were significantly related only to physical violence. |

| Krishnan (2005) | Survey | 397 | • Belonging to a lower caste and poor households, and alcohol consumption are risk factors for IPV. |

| Chandra et al. (2003) | Interview | 146 | • Sexual IPV ( e.g., sexual coercion) is not associated with any sociodemographic, psychiatric, or substance use. |

| Thakur (2001) | --- | --- | • For women, education and occupation are protective factors from IPV.

• Women’s empowerment, and awareness about their reproductive rights, are the main vital factors to deducting gender-based violence in society. |

3.1.1. Demographic Risk Factors of IPV

Several studies have identified different antecedents of IPV in India. Income, education [ 10], unemployment [ 38], age at marriage, gender, caste and religion, type of marriage, and marital duration are some risk factors for IPV [ 10, 36]. Subodh et al. (2014) found that IPV was linked with the higher age of the husband, lower education or unemployment of either spouse, lower family revenue, and a nuclear family structure [ 38]. In most patriarchal societies, husbands are the sources of income. The majority of abused women relied on their husbands for financial support and other expenses [ 17]. Lack of economic resources [ 39] and dependence are linked with violence [ 2]. Similarly, it is possible to generate stress, frustration, and a sense of insufficiency for failing gender role expectations among impoverished people, which in turn creates violence among couples [ 40]. However, there are studies inconsistent with these results. Raj et al. (2018) reported that women’s earnings did not predict IPV [ 41]. Similarly, studies show that more than one-third of women in India experience physical or sexual violence sometime in their lifetime. Among them, Krishnan (2005) found that women belonging to lower castes were more likely to report violence [ 4]. One of the reasons for the vulnerability of domestic violence among lower-caste women is a more conservative gender attitude among them [ 42].

Even though the factors mentioned above act as risk factors for IPV, some other elements act as protective factors for IPV. Increasing levels of education among women are crucial to reducing IPV against women [ 43]. It acts as a protective influence by altering society’s attitudes toward the acceptability of the mistreatment of women [ 44]. Additionally, Thakur (2001) reported that education and occupation play an essential positive role in reducing gender-based violence, which suggests that women’s development, awareness about reproductive rights, and empowerment are the main key factors in reducing gender-based violence [ 45].

3.1.2. Cultural Risk Factors of IPV

Nowadays, IPV is recognized as a sociocultural problem [ 32]. Cultural normalization of abuse or violence, gender role expectations, and dowry are the foremost cultural risk factors of IPV against women in India [ 8, 36, 46]. These deeply rooted patriarchal attitudes internalized in men tend to develop IPV perpetration behavior among men [ 47]. In a patriarchal society like India, a man has a right to correct and discipline women’s behavior through violence [ 35]. Mitra and Singh also found similar results, stating that, in India, a man is socially superior and has the right to assert power over women [ 48]. This perceived marital power leads to violence [ 49]. Besides, a study by Begum and Colleagues (2015) found that women who accept or justify their partner’s abuse are at twice the risk of domestic violence than women who do not justify it [ 50]. Another study by Bibi et al. (2014) found that wives being disobedient and making arguments were the most common instigating factors for violence among couples [ 51]. Furthermore, Levinson (1989) suggests that wife-beating happens more often in cultures where men have financial and decision-making power in the household, women do not have easy access to divorce, and adults use violence to resolve their conflicts [ 52]. In particular, structural inequalities between men and women, rigid gender roles, and the concept of manhood connected to dominance, male honor, and aggression contribute to increasing the risk of partner violence [ 53]. John et al. (2017) argued that gender beliefs and attitudes are developed in an individual during the early period of their life [ 54]. Gender socialization has a role in it. The process of learning and internalizing societal gender norms or rules of society, which are developed by connection with the people of a society, is called gender socialization. This gender role belief defines a woman’s status within marriage [ 54]. Due to the predetermined gender roles within marriage, women often rely on their husbands for socioeconomic survival [ 17], have a lower status in their marriages, and are more likely to experience gender-based violence [ 25, 55]. It might be why Indian women are more prone to gender-based violence. However, if husbands reported greater gender equality ideologies, wives were less likely to report IPV [ 56]. Furthermore, when a woman’s first kid is a female rather than a male, they are more likely to report psychological, physical, and sexual IPV [ 57]. The result revealed the son’s preference in Indian society. In India, masculinity ( e.g., controlling behavior and gender inequitable attitudes) strongly determine men’s preference for sons over daughters as well as their tendency for violence towards an intimate partner [ 58]. The son preference is often the result of the benefits of having male children and drawbacks of having female children in India. The one reason for such preference is dowry. It is a custom in India and is defined as any property or financial payment given to the groom by the bride’s family during the marriage. It is another cultural risk factor for violence among couples if the demands are not met [ 59]. Dowry-related violence often results if the bride’s parents have not met the dowry demands of the groom’s family, withholding of dowry, and/or dowry does not satisfy the groom/groom’s family [ 60]. Prasad et al. (1988) argued that many dowry disputes either end in the death of the bride or the suicide of the bride [ 60].

3.1.3. Individual Risk Factors of IPV

According to the social learning theory of violence, using violence to resolve conflict is often learned through observing parents or other adults during childhood. Many studies reported that experiencing or witnessing violence in childhood is associated with developing violence-perpetration behavior in an individual [ 61, 62]. Witnessing violence [ 63], Childhood abuse, alcohol [ 56], and drug use are the main individual risk factors of IPV against women in India [ 8, 36]. Personal history of violence in the family stemmed as a powerful causal factor for the perpetration of partner aggression by men. The abuse was higher among women whose husbands had either victimized violence or had witnessed their mothers being abused or harmed [ 40]. Although men who abuse their spouses often have a personal history of violence in their background, not all men who witness or suffer abuse become abusive [ 64].

Similarly, Sabri et al. (2014) found that alcohol use by husbands, jealousy, suspicion, control, and emotionally and sexually abusive behaviors were also related to an augmented probability of women experiencing severe IPV and injuries [ 63]. A higher prevalence of IPV was associated with alcohol use among couples in India [ 38]. Additionally, Subodh et al. (2014) found that the prevalence of spousal IPV was higher among alcohol-dependent and opioid-dependent men [ 38]. Furthermore, Patra et al. (2018) argued that heavy drinking could cause marital conflict and dissatisfaction among couples, and it may lead to IPV, suggesting that the use of alcohol and other drugs could increase aggressiveness and IPV in an individual [ 2]. Riggs and O’Leary (1996) developed a ‘model of courtship aggression’ to explain IPV [ 65]. According to the model, two components can stem aggression between couples: i.e., background and situational factors. These factors contribute to the development of aggression between couples. The background component comprises historical, societal, and individual characteristics. These factors might comprise a history of childhood abuse, exposure to violence in childhood, personality characteristics, a history of the use of aggression, psychopathology, social norms, and attitudes toward aggression to resolve conflicts. The situational components are the situation or setting the place for violence to happen (including expectations of the outcomes of the violence, interpersonal conflict, intimacy levels, and substance use). Interaction among these factors determines the intensity of the conflict and the chance of violence occurrence [ 62].

3.2. Risk Factors of IPV against Men

Table 2 in the appendix shows the antecedents of IPV against men. According to Straus (2005), IPV is bidirectional [ 13]. Estimates in the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) by the US indicate that male victimization is also a significant public health problem. The case of men is different from women in India. Changes in power dynamics among couples, economic independence of partners, and control over the economy and resources act as the major risk factors of IPV, especially against men [ 7]. For bidirectional physical violence, earning a partner with education up to graduation is one risk factor [ 10]. Malik and Nadda (2019) reported that unemployment of the husband was the major reason (60.1%) for partner violence, followed by arguing/not listening to each other (23%) and addiction of the perpetrator (4.3%). Additionally, uncontrolled anger, ego problems, etc., are other reasons for perpetuating IPV [ 10]. Similar results were found in another study by Lupri and Gardin (2004) [ 66]. According to them, unemployment, low income, personal bankruptcy, career setbacks, working overtime to make ends meet, and sustained economic uncertainties are risk factors linked with higher abuse rates. Additionally, they found that younger men seem to be at risk of experiencing partner violence compared to older men.

3.3. Literature addressing Consequences of IPV in India

Tables 3 and 4 in the appendix show studies on the consequences of IPV In India. Studies show a significant impact of IPV on mental health [ 2, 67-70]. Being the victim of physical, verbal, or sexual IPV increases the chance of negative mental health consequences [ 71]. The psychological consequences of IPV include depression [ 72], PTSD, suicidal ideation, and anxiety [ 36, 66]. Additionally, women who are victims of partner violence are more likely to report poor marital relationship quality [ 73], higher levels of distress, and lower resilience than women who did not [ 69]. Moreover, it can happen in both sexes; however, it is more prevalent among women in developing countries like India with a patriarchal mindset. Men also have similar experiences. Psychological consequences of IPV among men include upset, confused, or frustrated feelings of hurt or disappointment, low self-esteem, anxiety, and depression [ 66]. In a study, Kumar (2012) reported that stress, suicidal ideation, frustration, and alcoholism are other IPV consequences among men in India [ 7]. The study also reported that verbal abuse is the most common violence against men by women. Even if the men are victims of IPV, in a male-dominated society, sharing their suffering is a matter of shame [ 7]. So, most men are not ready to share their experiences [ 11].

| Author & Year | Method | Sample | Major Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malik &Nadda (2019) |

Interview

Quantitative |

1000 | • Low income, low education, nuclear family structure, and alcohol use are antecedents of IPV.

• Earning a spouse with education up to graduation is the risk factor for bidirectional physical violence among couples. |

| Kumar (2012) | Interview | --- | • Changing power dynamics, economic independence, and control over economy and resources are the main risk factors of IPV especially against men. |

| Lupri, & Grandin, (2004) | Literature review | -- | • IPV has physical consequences (Physical injuries)

• unemployment, low income, personal bankruptcy, career setback, working overtime to make ends meet, and sustained economic uncertainties are risk factors linked with higher abuse rates. • Additionally, they found that compared to older men, younger men seem to be at risk of experiencing partner violence. |

| Author & Year | Study Design | Method | Research Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chatterji et al. (2023) | Quantitative | N=1084 women and 1084 men

Age: 18–29 years |

• Marital quality is negatively associated with physical/sexual IPV.

• Poor marital quality of Men marital quality is linked with women’s experience of sexual IPV. • Partner’s’ experience of marital quality is positively related to men’s experience of marital quality. |

| Bondade et al. (2021) | Quantitative | 115 females

Age:18-45 |

• Women who experienced IPV have a risk of developing an anxiety disorder and depression. |

| Vranda et al. (2018) | Qualitative | N=100

18 to 55 years |

• The majority of women reported moderate IPV from their intimate partner.

• The chance of getting a mental disease is higher in women who have experienced domestic abuse/IPV. |

| Richardson et al. (2019) | Quantitative | 3010 women | • The relationship between IPV and women’s mental health may be significantly mediated by psychological abuse and controlling behavior. |

| Patel et al. (2019) | Quantitative | N = 232 married women

Age = 42.06 |

• More depressive symptoms are seen among women who experienced IPV than women without IPV. |

| Patra et al. (2018) | Literature review | -- | • IPV has mental and health consequences. |

| Satheesan & Satyanarayana, (2018) | Survey | N=46 | • Psychological distress is positively associated with IPV. |

| Kalokhe et al. (2017) | Literature review | 137 quantitative studies | • Mental health consequences of IPV are depression, anxiety, PTSD, somatic symptoms, and suicidal ideation/attempts. |

| Stephenson et al. (2013) | Quantitative | Data retrieved from NFHS-2

N= 6,303rural married women Age: 15-49 |

• Victimization of physical, verbal, or sexual IPV is negatively associated with mental health (feeling persistently under strain, depressed, and sleep disturbances due to worry). |

| Kumar (2012) | Interview | -- | • IPV victimization among men can lead to stress, suicidal ideation, frustration, and alcoholism. |

| Varma et al. (2007) | Structured interview | N= 203 | • Prevalence of depression, somatic, and PTSD symptoms, are more among people who have experienced abuse or sexual coercion. |

| Kumar et al. (2005) | Quantitative | N=9938 Women

Age: 15-49 |

• Domestic spousal violence is strongly negatively associated with mental health. |

| Author & Year | Study Design | Method | Research Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avanigadda, & Kulasekaran, (2021) | Quantitative | Data retrieved from National Family Health Survey (NHFS)-4 (2015-2016)

N=24882 Women Age: 15–49 |

• Abuse against women, physically, emotionally, and sexually, during pregnancy can lead to pregnancy or maternity-related issues. |

| Bondade et al. (2021) | Quantitative | 115 females

Age:18-45 |

• Prevalence of STI symptoms is more among women with IPV than those without it. |

| Patrikar et al. (2017) | Quantitative | The data retrieved from NFHS-3 (2005-2006)

N= 102946 (women and men) |

• Among Indian women, IPV has a positive association with HIV.

• It infers a new connection between IPV and HIV. |

| Kalokhe et al. (2017) | Literature review | 137 quantitative studies | • IPV can cause Asthma, HIV, other STDs, and maternal health-related issues. |

| Shohani et al. (2013) | Quantitative | Age: minimum 16

N= 47 |

• Injuries can result from IPV among them Fractures are the most identified injury.

• More than one-third of injuries are fractures. Among that neck and spine injuries are the most reported. |

| Scribano et al. (2012) | Survey | N= 10,855

Age:19.9 |

• IPV and perinatal outcomes, such as gestational age and birth weight are not associated.

• In longitudinal follow-up, IPV was associated with reduced rates of contraceptive use and greater rates of quick recurrent pregnancies. |

| Chandra et al. (2003) | Quantitative | N= 146 | • Threatened or forced sexual intercourse is the most commonly reported sexual violence.

• Women with a history of abuse were more likely to report HIV. |

| Author | Method | No. of Participants | Findings/aim |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kalokhe et al. (2019) | Intervention

Ghya Bharari Ekatra (Take a Flight Together) |

3-5 newly married couples | Prevention of IPV |

| Satyanarayana et al. (2016) | Intervention

Integrated cognitive–behavioral intervention (ICBI) |

177 men | Compared to Treatment as usual (TAU) participants in the Integrated cognitive–behavioral intervention (ICBI) group reported significantly lower IPV perpetration and their wives reported significantly lower depression, anxiety, and stress levels at 3-month follow-up. |

The literature provides evidence of the association between IPV and different physical health issues [ 3, 18, 36]. Physical health consequences of IPV include physical injuries [ 66], HIV [ 20] and other STDs [ 74], Asthma, and pregnancy/maternal health-related issues [ 36, 75, 76]. The most commonly reported bodily injury are fractures (39%), among which the spine and neck (28%) are the parts most frequently injured [ 74]. Moreover, injuries are not only the consequences of IPV; there is a strong association between IPV and STIs [ 77]. Correspondingly, Bondade (2018) also found that STI symptoms were more prevalent in women with IPV than those without it [ 77]. Similarly, Partrikar (2017) found a rising possibility that HIV status and IPV are significantly positively correlated among married Indian women [ 78]. HIV reporting rates were higher among women with a history of abuse [ 20]. IPV, such as sexual and physical assault, also leads to complications during the pregnancy period [ 75]. Ackerson and Subramanian (2009) discovered that mothers who experienced physical IPV showed higher mortality rates in their children, specifically among infants [ 79]. In some cases, physical IPV during pregnancy was associated with lower birth weight, premature delivery, and reduced breastfeeding among IPV victim mothers [ 28]. Contrary to this, another study found that IPV had no significant impact on perinatal outcomes such as gestational age and birth weight [ 76].

3.4. Interventions to Mitigate IPV in India

Table 5 in the appendix shows intervention studies on IPV in India. Western scholars have developed several interventions to tackle IPV. However, very few interventional studies have been conducted in India to reduce IPV. Several studies suggested a need for such interventions in India [ 2]. For that, Multilevel-Multicomponent intervention studies needed to be developed; such programs can be built with the community. Multilevel-multicomponent programs are more challenging compared to individual-level interventions. Developing such approaches is the key to the long-term prevention of IPV. It is the most under-researched area in IPV [ 16].

Satyanarayana et al. (2016) conducted an intervention to reduce IPV in India [ 80]. The research was to examine the effectiveness of Integrated cognitive-behavioral intervention (ICBI) in reducing IPV perpetration among alcohol-dependent men and improving mental health among their wives and children. The study found that compared to treatment-as-usual (TAU) patients, IPV perpetration was less common among participants in the ICBI group. Additionally, in a 3-month follow-up, their partners reported lower depression, anxiety, and stress levels. Similarly, Kalokhe et al. (2019) developed a dyadic intervention (Ghya Bharari Ekatra’ (Take a Flight Together)) to prevent IPV among newly married couples residing in slum communities in India [ 81]. The intervention has games, discussions, self-reflection, and skill-building exercises. The sessions covered topics like enhancing relationship quality time, self-esteem and resilience, communication and conflict management, goal setting and implementation, sexual communication and sexual health, reproductive health knowledge, and redefining and challenging norms surrounding IPV occurrence. Even though some interventions are developed to reduce IPV, early identification and prevention is the best way to reduce IPV among couples.

5. IMPLICATIONS

The synthesized evidence from the review helps us to understand the antecedents and consequences of IPV and intervention studies conducted among married couples in India. This, in turn, might help policymakers such as law and enforcement, legal bodies, and health care organizations to improve or reform existing policies and formulate new policies on marriage, divorce, health and family welfare, and mental health in general. The reformation or formulation of new policies in civil and criminal legal frameworks on marriage and domestic violence should focus on strengthening and expanding laws defining rape and sexual assault within marriage, women’s civil rights, and civil rights related to divorce, property, child support, and custody. Furthermore, psychosocial interventions that would alleviate the effects of conflict and IPV are rarely attempted in the Indian cultural context. Hence, this review would also help future researchers in the development of new community-based programs to reduce IPV for married couples.

CONCLUSION

In light of the above, it is understood that IPV is a serious and widely prevalent under-recognized issue. However, few studies were conducted in the Indian cultural context that explored the antecedents and consequences of IPV. Additionally, very few IPV intervention studies were conducted in India. Through early prevention, screening, and intervention, we can reduce the number of IPVs in India. So, more studies should be done in the Indian cultural context to address the issues of IPV. To manage IPV, we must adapt or develop an indigenous intervention for IPV.

Along with that, in the future, researchers should attempt to assess the impact of IPV among children and adolescents. Researchers should also take the initiative to create awareness among family members about the adverse effects of IPV on their children. Furthermore, research on IPV among same-sex couples, couples in a live-in relationship, male victims, and IPV perpetration of women are hardly studied in the Indian cultural context. Such community-based studies should be explored in the future.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| IPV | = Intimate Partner Violence |

| NFHS-4 | = National Family Health Survey |

| ICBI | = Integrated cognitive-behavioral intervention |

| TAU | = Treatment-as-usual |

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines and methodology were followed.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIAL

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

PRISMA checklist is available as supplementary material on the publisher’s website along with the published article.

Supplementary material is available on the publisher’s website along with the published article.