All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

You Got to Look Right! Mapping the Aesthetics of Labor by Exploring the Research Landscape using Bibliometrics

Abstract

Background:

There has been a lot of research interest in ‘aesthetic labor’, especially since 2012. Research has established a strong relationship between aesthetic labor and emotional labor, especially in the service industry. Various constructs have been studied in the context of aesthetic labor, e.g., gender (studies have examined the ways in which gender affects the performance of aesthetic labor and the consequences of gendered expectations for individuals in different professions), body image (aesthetic labor can have significant effects on an individual's body image, as they may feel pressure to conform to certain beauty standards in order to succeed in their profession), self-presentation (studies have examined the relationship between aesthetic labor and self-presentation, including the ways in which individuals may use aesthetic labor to manage their identities), and customer satisfaction (studies have examined the impact of aesthetic labor on customer perceptions of service quality, as well as the ways in which aesthetic labor can be used to improve customer experiences). However, there is a dearth of studies that comprehensively analyze all available literature on aesthetic labor. Therefore, this study aims to bridge this gap.

Aims:

This study aims to explore the research that appears in the Scopus database and provide a comprehensive review of the literature published on aesthetic labor to find the past and current trends and explore the future scope of research.

Objectives:

The objectives of this study are to find the most influential articles on ‘aesthetic labor’, explore the spread of research over the years, find the leading sources and countries as far as publications on aesthetic labor are concerned, and investigate the emerging themes in the area of ‘aesthetic labor.’

Methods:

The study used VOS viewer to analyze the articles that emerged in the Scopus database by applying the keyword, ‘aesthetic labor’. The search results were restricted to publications in the domains of social sciences, business management and accounting, and psychology, which resulted in 180 articles. Bibliometric analysis (co-occurrence of keywords) was carried out on these 180 publications.

Key Results:

Work, employment, and society is the leading source for publications. Maximum research in said area has emerged from the United Kingdom, followed by the United States. The themes are the relationship between aesthetic labor and consumption, emotional labor, and gender inequality, emphasizing the need for fair appearance standards and support for employees due to the stress and burnout associated with presenting oneself in a certain way to create a positive customer experience. Intersectionality of discrimination in aesthetic labor, including appearance-based recruitment, emotional exhaustion, and commodification of workers in service industries, negatively impacts their well-being and job satisfaction. The last theme is an adaptation of industry to appeal to male customers and its implications for the gendered nature of aesthetic labor.

Conclusion:

This study explores important themes that emerged after doing a comprehensive review of the literature published on “aesthetic labor.” Emotional labor discrimination, which is closely associated with aesthetic labor, is the area that has garnered the interest of researchers. However, the education system and the value it assigns to aesthetic labor constitute a further area of inquiry. Understanding how aesthetic labor is perceived and performed in the context of social media, notably photo and video-sharing platforms, is an additional crucial area of study.

1. INTRODUCTION

The concept of aesthetic labor emanates from the general history of labor, especially emotional labor [1]. The term emotional labor was first introduced in the 1960s to describe the work done by flight attendants that required them to suppress their emotions and put up a smile to create a pleasing atmosphere for the customers [2]. Emotional labor is a demand of the job of frontline workers wherein they are expected to display certain emotions, e.g., happiness [3]. The concept of aesthetic labor was built on the concept of emotional labor [4]. The term aesthetic labor caught the attention of researchers in the 1990s. One study traces the evolution of labor right from the start of the industrial era and argues that labor has become more aestheticized in modern capitalist society [5]. The term aesthetic labor concerns the management of physical appearance and emotions in the workplace, especially in customer-facing or service jobs [6]. Aesthetic labor plays a key role in creative industries [7]. Moreover, aesthetic labor is the practice of assessing, supervising, and regulating employees based on their physical appearance [8]. Over the past two decades, the concept of aesthetic labor has gained increasing attention from scholars across multiple fields, including management, sociology, and psychology [9]. Researchers have explored the concept of aesthetic labor in relation to gender, race, and ethnicity and the impact of aesthetic labor on worker’s emotional well-being [10]. The concept is particularly of interest to the service, fashion, and retail industries, where workers are expected to manage their emotions and project a captivating physical appearance of themselves as part of their job [11].

This type of labor is becoming extremely prevalent nowadays due to the growth of the service economy, and it has been linked to several issues, such as objectification, gender, biases for certain jobs, stress, and burnout [12]. The emergence of aesthetic capabilities is indicative of the increasing significance of aesthetic labor in interactive services [13]. For example, employers increasingly demand their employees to have an appearance that they deem “right”, meaning that they “look good” and “sound right” in retail and hospitality service encounters [13].

Some organizations use aesthetic labor to differentiate their 'value propositions'; however, by concentrating on the physical appearance of their employees, they raise issues of sexualizing labor for commercial purposes [14]. Some industries, such as the entertainment industry, recruit people based on physical attributes, which results in bias toward those who do not fulfill the criteria of expected physical attributes, which may lead to stress and burnout [15].

Since 2012, research on “aesthetic labor” has acquired momentum due to its significance in the service industry. Aesthetic labor in the hotel industry influences consumer perceptions and satisfaction [16].

The significance of maintaining a professional appearance is emphasised by the fact that employee appearance mediates the relationship between aesthetic labor and service performance in the service business [17]. Employees are increasingly believed to be mouldable to reflect the organisational aesthetic [18]. Thus, it becomes an important concept to study and explore.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

In recent years, aesthetic labor has received increasing attention, as it is a type of work that is becoming more prevalent in service industries. Such laborers are considered to have embodied capacities and attributes right at the time of their entry into the organisation. Such attributes are further enhanced, developed, and commodified by employers in a manner that aligns with the aesthetically pleasing desired image of the organization and thus impacts the service interaction positively [6]. The aesthetic component of interactive service work is gaining importance. This is reflected in both industrial sociology and organisation studies on the topic [19]. In recent times, even the definition of soft skills required in certain sectors, such as retail, has started including aesthetic labor [20].

This literature review is intended to provide an overview of the existing literature on aesthetic labor and critically evaluate its implications for organisations and employees. Seminal work by Hochschild depicts how an employee has to maintain an emotional image that is aligned with the employer’s or organisation’s image, and it can lead to exhaustion and emotional dissonance [2]. The study further establishes that an individual undertakes the effort in planning and controlling to display emotions that are desired by the organisation during one-on-one interactions with customers, and it can lead to burnout and job dissatisfaction [21]. The job demands that come with emotional labor may result in burnout [22]. However, this dissatisfaction can be mitigated if the workers are provided social support [23, 24]. It is further strengthened by a study that argues that those who can effectively regulate their emotions enjoy greater job satisfaction and experience less emotional exhaustion [25]. Aesthetic labor has quite a few implications for organisations. Emotional dissonance that comes with aesthetic labor, as it puts the extra burden on projecting a desirable physical self, depletes the emotional resources and results in turnover intentions [22]. Aesthetic labor also aids in a complex form of impression management. A study conducted on erotic dancers found that the dancer engages in extensive emotional and aesthetic labor to put up her ‘work self’ [26]. While the burden that aesthetic labor puts on the emotional makeup of employees is well established, a study segregated this burden into 3 dimensions: organisational requirements in terms of aesthetics, pressure exhibited by customer service, and burdens carried on in time of work [27].

Although job satisfaction is negatively related to aesthetic labor and positively related to turnover intentions, this relationship is moderated by customer orientation [28]. Aesthetic labor does have a positive impact on customer satisfaction. Customer satisfaction and loyalty are enhanced by both emotional labor and aesthetic labor [16]. Another reason why employers want to engage in aesthetic labor is social comparison theory, i.e., a general theory that establishes how consumers may react to service providers who appear more or less alike. To some extent, a similar appearance (i.e., having employees in uniform, maintaining the same hairstyle, etc.) is an effective aesthetic labor strategy insofar as it fosters feelings of genuine belonging [29]. A unique view on aesthetic labor is provided by a study that identifies three ways in which aesthetics are acknowledged to contribute to an organisation: aesthetics of an organisation, aesthetics in the organisation, and aesthetics as an organisation [18]. The study argues that employees are viewed not only as “software” but also as “hardware,” meaning that they can be modelled to reflect the organisational aesthetic. Furthermore, it has been well established by researchers that aesthetic labor is not just restricted to looking good, but it also encompasses sounding right [30, 31]. Thus, the phenomenon of aesthetic labor also encompasses the aural aspect.

How different cultural dimensions and country social values impact the perception of aesthetic labor is another area that has caught the attention of researchers. The study provided an international comparison of aesthetic labor in interactive service work, contending that the nature of this work differed between nations and industries [6]. It has been discovered that aesthetic labor has both positive as well as negative effects on employees. On the one hand, it can increase employees' job satisfaction and sense of self-worth because they can use their appearance to generate positive customer experiences [32]. On the other hand, employees who are required to use their appearance as a marketing instrument for the organisation may experience feelings of objectification and commodity [33]. In addition, aesthetic labor can reinforce existing gender and racial hierarchies since women and ethnic minorities are frequently required to perform more aesthetic labor than their male or white counterparts [34]. A study [35] highlighted the complexities faced by women, especially in the professions where appearance is paramount, in navigating between self-acceptance and societal pressures. Another study [36] identified decision-making orientation toward recruitment of aesthetically rich applicants, evidently seen in the Indian hospitality sector.

Lastly, the literature on aesthetic labor emphasises the need for additional study in this area. There is a lack of research on how employees in various contexts, such as non-Western countries or industries other than service work, experience aesthetic labor [6]. In addition, gendered and racialized aspects of aesthetic labor, as well as the impact of new technologies, such as social media and facial recognition, must be investigated further. By addressing these research voids, academics can gain a deeper comprehension of the complexities of aesthetic labor and its implications for organisations and employees.

3. RESEARCH QUESTIONS

Q1. What are the most influential articles on ‘aesthetic labor’?

Q2. How is the spread of research over the years?

Q3. What are the leading sources and countries as far as publications on ‘aesthetic labor’ are concerned?

Q4. What are the emerging themes in the area of ‘aesthetic labor’?

4. METHODS

This paper is based on bibliometric analysis. Bibliometric analysis is a quantitative technique for analysing and quantifying the characteristics of scientific publications, such as journal articles, books, and conference proceedings [37]. This method strives to understand the connections between journal citations and summarise the current state of affairs in relation to an emerging research area. The data were retrieved from Scopus for this research. For analysis, a Visualization Of Similarities (VOS) viewer was used, which allowed visualization of bibliometric maps. This methodology enables us to efficiently collect the literature and identify the connections between selected publications and potential alternatives.

The keyword used in the Scopus database was “aesthetic labor”, which fetched 180 publications when the search was restricted to publications in social sciences, business, management and accounting, and psychology domains. The analysis was carried out on these 180 publications.

The received results were downloaded in CSV file format so that VOSviewer may process them and be used to visualise and analyse the bibliometric form's trends.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Most Influential Publications

To gauge the understanding of the most prominent or influential publications on aesthetic labor, we found the most cited articles using the VOS viewer. A summary of the same is given in Table 1.

| Document Title | Authors | Journal Title | Total Citations |

|---|---|---|---|

| The labor of aesthetics and the aesthetics of organization | Witz A., Warhurst C., Nickson D. | Organization | 410 |

| Employee experience of aesthetic labor in retail and hospitality | Warhurst C., Nickson D. | Work, Employment, and Society | 242 |

| Aesthetic labor in interactive service work: Some case study evidence from the 'new' Glasgow | Warhurst C., Nickson D., Witz A., Cullen A.M. | Service Industries Journal | 235 |

| Looking good and sounding right”: Aesthetic labor and social inequality in the retail industry | Williams C.L., Connell C. | Work and Occupations | 214 |

| The importance of attitude and appearance in the service encounter in retail and hospitality | Nickson D., Warhurst C., Dutton E. | Managing Service Quality | 190 |

| Who's got the look? emotional, aesthetic, and sexualized labor in interactive services | Warhurst C., Nickson D. | Gender, Work and Organization | 160 |

| Keeping up appearances: Aesthetic labor in the fashion modelling industries of London and New York | Entwistle J., Wissinger E. | Sociological Review | 140 |

| Gendered work meets gendered goods: Selling and service in clothing retail | Pettinger L. | Gender, Work and Organization | 110 |

| When production and consumption meet: Cultural contradictions and the enchanting myth of customer sovereignty | Korczynski M., Ott U. | Journal of Management Studies | 110 |

| Workers, managers, and customers: Triangles of power in work communities | Lopez S.H. | Work and Occupations | 107 |

The most cited publication focuses on the ways in which aesthetic labor is used by organizations to create a certain image or brand [19]. The paper highlights the importance of aesthetic labor in contemporary organizations and provides a framework for understanding its role in organizational power dynamics. A study [38] highlighted the challenges faced by employees who engage in aesthetic labor in retail and hospitality and called for greater recognition and value for this type of work. A case study was conducted on interactive service work in New Glasgow to explore the experiences of workers and the strategies they use to manage their aesthetic labor [6]. Furthermore, Williams, C. L. and Connell, C [11]. emphasised the ways in which aesthetic labor in the retail industry can contribute to social inequality and stratification. Dennis, N. et al. [13] highlighted the significance of employee demeanour and appearance in service interaction and suggested that businesses can use strategic management practices to enhance these factors and improve customer satisfaction and business performance. Moreover, Warhurst, C. and Nickson, D. [39] argued that employees in service industries are often required to perform emotional, aesthetic, and sexualized labor and discussed the challenges and implications of this type of work for workers and employers. The work by Entwistle, J. and Wissinger, E. [40] examined the ways in which models perform aesthetic labor to meet the expectations of the fashion industry and discussed the implications of this type of work for models' identity and experiences in the industry. Pettinger, L [41]. demonstrated that gendered expectations and norms influence both the types of products sold and the ways in which employees are expected to interact with customers and discussed the implications of this for workers and consumers in the industry. The research work by Korczynski, M. and Ott, U. [42] argued that the notion of customer sovereignty, where customers have complete control over their consumption choices, is a myth that ignores the complex social and cultural dynamics that shape consumption. Lastly, the work by Lopez, S. H. [43] used case studies to examine the ways in which power is negotiated and contested among workers, managers, and customers and discussed the implications of these power dynamics for workplace culture and employee experience.

| Year | No. of Publications | Annual Growth Rate |

| 1980 | 1 | 0 |

| 2000 | 1 | 0 |

| 2001 | 1 | 0 |

| 2003 | 2 | 100 |

| 2004 | 2 | 0 |

| 2005 | 5 | 150 |

| 2006 | 2 | -60 |

| 2007 | 2 | 0 |

| 2008 | 5 | 150 |

| 2009 | 4 | -20 |

| 2010 | 4 | 0 |

| 2011 | 4 | 0 |

| 2012 | 12 | 200 |

| 2013 | 10 | -16 |

| 2014 | 11 | 10 |

| 2015 | 12 | 9 |

| 2016 | 5 | -58 |

| 2017 | 13 | 160 |

| 2018 | 13 | 0 |

| 2019 | 19 | 46 |

| 2020 | 16 | -15 |

| 2021 | 21 | 31 |

| 2022 | 13 | -38 |

| 2023 | 2 | -84 |

| Total | 180 | |

| Document Type | Number of Publications | Percentage of Total Publications |

|---|---|---|

| Articles | 147 | 82 |

| Book Chapters | 16 | 9 |

| Review Papers | 11 | 6 |

| Conference Papers | 4 | 2 |

| Others | 2 | 1 |

| Source | No. of Publications | Citations |

|---|---|---|

| Work, Employment, and Society | 13 | 640 |

| Economic and Industrial Democracy | 6 | 206 |

| Gender, Work, and Organization | 6 | 293 |

| International Journal of Hospitality Management | 4 | 163 |

| Equality, Diversity, and Inclusion | 4 | 16 |

| Journal of Consumer Culture | 4 | 131 |

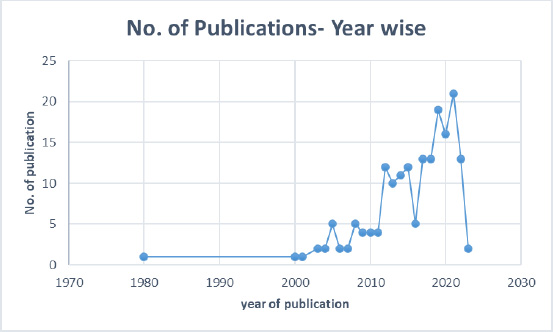

5.2. Year-wise Publications

The first publications in concern of research appeared in 1980. For the next 2 decades, there appeared to be no publication; thus, the research interest in the area of ‘aesthetic labor’ did not gain momentum until 2000. Table 2 and Fig. (1) depict the year-wise publications.

For the early decade of the 21st century, i.e., 2000-2010, a total of 28 papers were published. From 2001-2021, 136 papers were published, indicating a growth rate of 385%.

It is evident from Fig. (1) that the research interest gained momentum from 2012 onwards.

5.3. Publications by Document Type

As mentioned in Table 3, 82% of publications are articles, followed by book chapters (9%) and review papers (6%). The other papers include notes. Moreover, all publications are in English language. There is no published research (out of the 180 publications that are in the scope of this study) in any other language except English.

The predominance of articles (82%) indicates rigorous, peer-reviewed academic interest in the topic. Book chapters (9%) suggest detailed exploration, while review papers (6%) reflect synthesis and gap identification. The exclusivity of English in publications points to its global academic appeal but also suggests the potential underrepresentation of non-English perspectives, highlighting a need for more diverse linguistic contributions in future research.

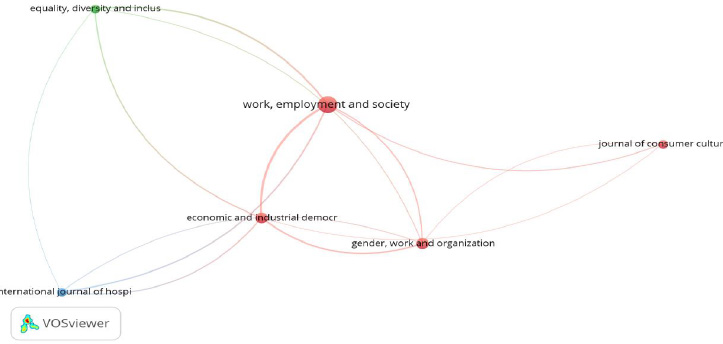

5.4. Publications by Source

Table 4 presents the top sources for publication, and the journal ‘Work, Employment, and Society’ emerges as the top source with 13 publications on its credit.

The first paper (out of the total 180 publications that constitute the scope of this paper) was published in the Journal, ‘Media, Culture, and Society’ in 1980.

The analysis of citations by the source is depicted in Fig. (2). When the threshold of the minimum number of documents of a source is 4, and the minimum number of citations of a source is 15, 6 sources meet the threshold, and they are segregated into 3 clusters. Work, Employment and Society (with links 5 and total link strength 42), Economic and Industrial Democracy (5/38), Gender, Work, and Organization (5/19), and Journal of Consumer Culture (3/5) belong to the red cluster (cluster 1). Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (4/17) belong to the green cluster (cluster 2). International Journal of Hospitality Management (4/15) belongs to the blue cluster (cluster 3).

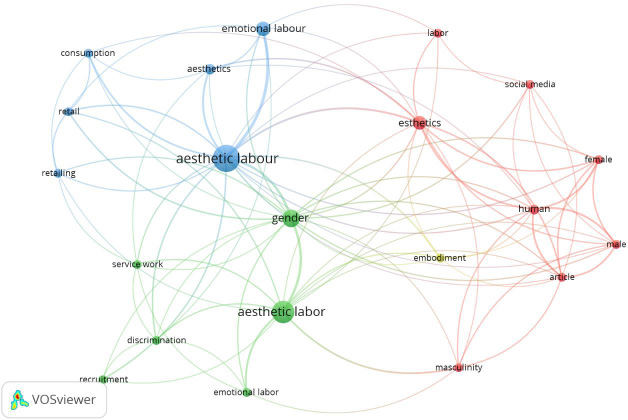

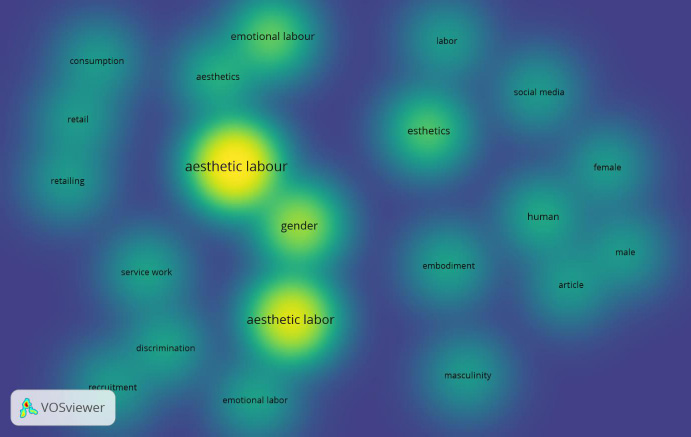

5.5. Co-occurrence of Keywords

The next analysis carried out is on the co-occurrence of keywords. The word's frequency in the article and its association with other keywords are displayed on the cloud map. Each term in the network is presented by a circle, the diameter of which is proportional to the number of publications in which it appears. Each colour corresponds to a set of terms organised into groupings. The connections between the various topics are shown by the clusters. Some restrictions have been applied to fetch more accurate results. By analysing all keywords using the full counting method and applying a threshold of 5 as a minimum number of occurrences of a keyword, 21 keywords out of 637 met the criterion. These keywords are segregated into 3 major clusters.

5.5.1. Cluster-1 (The Blue Cluster)

The blue cluster has keywords, such as aesthetic labor, aesthetics, consumption, emotional labor, retail, and retailing. Aesthetics is an important aspect of service work, particularly in industries that rely on face-to-face interactions with customers. Workers who are seen as aesthetically pleasing are often perceived as being more competent and trustworthy [38]. Consumption and aesthetic labor are interlinked. Aesthetic labor encourages consumption [44]. Emotional labor is a key aspect of aesthetic labor in service industries. Emotional labor and aesthetic labor are intertwined, and those workers who engage in aesthetic labor also engage in emotional labor. Workers who engage in aesthetic labor are not only required to present a certain appearance but also to manage their emotions to create a positive emotional experience for customers [4]. There is a lot of research done on aesthetic labor, specifically in the context of the retail industry. In retail, aesthetic labor embodies the store’s desired look, which can be demanding and stressful, as workers are required to constantly manage their appearance and emotions [45]. Aesthetic labor is often gendered in the retail industry, with women more likely to be employed in roles that require them to engage in aesthetic labor. This can lead to gender inequality in terms of pay and career advancement [34]. Sayan-Cengiz, F [46]. sheds light on the influence of appearance on retail employees' experiences in Turkey and highlights the need for more inclusive and diverse beauty standards in the workplace.

The concept of aesthetic labor and its relationship with consumption, emotional labor, and gender inequality, specifically in the context of the retail industry, emerged as a major theme from the blue cluster. The cluster highlights that workers in service industries, especially the ones who directly interact with the customers physically, are expected to present a certain appearance and manage their emotions well to offer a positive emotional experience to the customers. These forced displayed emotions contrary to the felt ones may cause stress and burnout. Sufferers, in the majority of cases, are women as they are the ones who are generally hired for such jobs requiring aesthetic labor and thus could be vulnerable to gender inequalities in terms of pay and career advancement. Additionally, the cluster also emphasizes the interlinked nature of aesthetic labor, emotional labor, and consumption.

5.5.2. Cluster-2 (The Green Cluster)

The green cluster has keywords, such as aesthetic labor, discrimination, emotional labor, gender, recruitment, and service work. Aesthetic labor can be a site of discrimination, particularly for workers who do not conform to dominant beauty standards [15]. Discrimination in aesthetic labor can contribute to underrepresentation and harassment of certain groups in the workplace [47]. Aesthetic labor is often gendered and racialized, with workers of color and women facing particular challenges in terms of discrimination and bias. A study was conducted in the business and management sector of Finland, a country with an international reputation for gender equality, and discovered that women faced additional pressures, such as ageing-related pressure in remaining energetic and youthful and enhancing the organization's image [43]. Cho, J [48]. investigated how contemporary female interpreters negotiate a market demand for beauty work in addition to language work to emphasise aesthetic labor as a gendered strategy for self-commodification in the patriarchal language market.

The aural dimension of aesthetic labor is also related to discrimination. Results of a study conducted in the USA suggest that managerial incumbents actively discriminate against applicants with Chinese, Mexican, and Indian accents in telephone-based job interviews, and all three accents are rated higher in non-customer-facing jobs than in customer-facing jobs. Applicants with a British accent, particularly males, perform well, and sometimes better than native speakers of American English [49].

Recruitment practices that rely on appearance-based criteria can also have negative effects on worker well-being and job satisfaction, as workers may feel pressure to conform to certain beauty standards and may be subject to discrimination and harassment [50]. However, in some cases, some forms of aesthetics can aid in the selection process. Timming, A. R [51]. demonstrated that body art could be used strategically to positively impart the brand of organisations, particularly those targeting a younger 'edgier' customer demographic. However, contradictory results were found in a study that indicated that visible body aesthetics, i.e., body art, may pose a significant barrier to employment [52].

The green cluster had the intersectionality of discrimination in aesthetic labor, particularly in terms of gender and race, and the adverse implications of appearance-based recruitment and selection practices on the well-being and job satisfaction of workers in the service industries as the theme. The cluster also highlights the challenges faced by workers performing emotional and aesthetic labor simultaneously, leading to emotional exhaustion and burnout. Additionally, it discusses the commodification of workers and their emotions in aesthetic labor-intensive industries, such as the retail industry.

5.5.3. Cluster-3 (The Red cluster)

The red cluster has keywords, such as aesthetics, female, human, labor, male, and masculinity. Aesthetic labor can involve a range of practices, including grooming, dressing, and the use of makeup and other beauty products. These practices can be used to create a particular image or brand identity for workers or organizations [29]. Fowler, J. G. et al. [53] examined the experiences of male fashion models in relation to “aesthetic labor,” or the use of physical appearance to create an image or brand identity. The authors argued that while aesthetic labor can be empowering, it could also reinforce gender norms and expectations, leading to experiences of vulnerability and objectification. Barber, K [54]. examined the process of masculinization of hair salons in the UK and the role of heterosexual aesthetic labor in this process. The author argued that the masculinization of hair salons was driven by a desire to appeal to male customers and was achieved through the use of marketing strategies that emphasized heterosexuality and masculinity.

| Cluster | Links | Total Link Strength | Occurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 (Blue) | 17 | 59 | 58 |

| 2 (Green) | 14 | 32 | 38 |

| 2 (Green) | 19 | 44 | 23 |

| 3 (Blue) | 7 | 21 | 15 |

| 1 (Red) | 13 | 29 | 13 |

| 3 (Blue) | 7 | 14 | 8 |

| 1 (Red) | 11 | 28 | 7 |

| 2 (Green) | 7 | 10 | 6 |

| 2 (Green) | 5 | 10 | 6 |

| 2 (Green) | 7 | 9 | 6 |

| 4 (Light green) | 7 | 10 | 6 |

| 1 (Red) | 10 | 23 | 5 |

| 1 (Red) | 8 | 19 | 5 |

| 1 (Red) | 5 | 6 | 5 |

| 1 (Red) | 9 | 21 | 5 |

| 1 (Red) | 7 | 13 | 5 |

| 1 (Red) | 7 | 8 | 5 |

| 2 (Green) | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| 3 (Blue) | 6 | 10 | 5 |

| 3 (Blue) | 6 | 13 | 5 |

| 3 (Blue) | 6 | 9 | 5 |

Red cluster explores gendered aspects of aesthetic labor, pivoting around the experiences of male workers in female-dominated industries, such as fashion modeling and hairdressing. Authors delved into the role of physical appearance to create an image or brand identity by reinforcing gender norms and expectations, leading to experiences of vulnerability and objectification. The cluster also examines the ways and means to be adopted by industries to appeal to male customers and its implications on workers in terms of the gendered nature of aesthetic labor.

Table 5 provides a summary of the most occurred keywords. After the word ‘aesthetic labor/aesthetic labor’, ‘gender’ comes next, followed by ‘emotional labor’ and ‘esthetics’.

The focus of the research is depicted in Figs. (3 and 4). The more concentrated the colors and bigger the word size, the more research has been conducted in the said field. As far as aesthetic labor is concerned, the research interest has been most around gender, esthetics, and emotional labor.

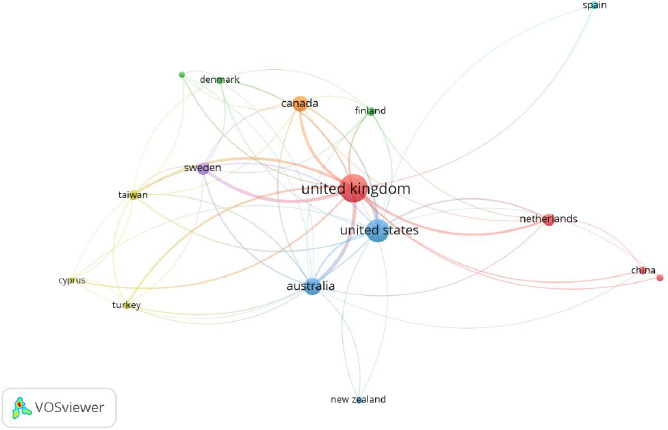

5.5.4. Publications by Countries

The next unit of analysis was selected as publication by country. By applying the threshold of 2 as the minimum number of documents from a country, 16/24 met the criterion. The United Kingdom has the highest number of documents (57), followed by the United States (37), Australia (20), Canada (15), Sweden (9), Netherlands (9), Taiwan (6), Finland (5), China (4), Spain (4), Turkey (3), Denmark (3), India (3), New Zealand (3), Cyprus (2), and Singapore (2). UK and USA combined have more than 59% of publications. The same is depicted in Figs. (3 and 5).

6. DISCUSSION

The findings of this research indicate that aesthetic labor is a significant aspect of work, particularly for employees who work in service-oriented jobs. Aesthetic labor involves not only the performance of job tasks but also the management of one's appearance, demeanour, and emotional expressions in a way that meets the expectations of the organization and its customers [2]. Our study has shown that employees who engage in aesthetic labor experience both positive and negative outcomes. On the positive side, employees who engage in aesthetic labor report a sense of pride in their appearance and work, and they often feel that their efforts lead to positive outcomes for the organization [55]. Additionally, they also feel that the way they present themselves at work is an expression of their identity, which can help them feel more authentic [56].

On the other hand, employees who engage in aesthetic labor may also experience negative outcomes. For instance, the need to present a certain appearance or demeanour can create a sense of inauthenticity [56], leading to emotional dissonance and exhaustion [15]. The pressure to manage their appearance can also create anxiety and stress for employees, leading to burnout [57]. Entwistle, J. and Wissinger, E [40]. highlighted that to keep up with the norms and to fully embody the concept, workers sometimes have to take extreme measures (such as dieting) as they not only have to keep up their appearance but also maintain it. Moreover, it is important to recognize that not all employees experience the same level of aesthetic labor, and this may be influenced by factors, such as gender, age, and race. For example, research has shown that women and people of color are often held to higher appearance standards than their male or white counterparts, leading to increased levels of aesthetic labor [58]. One more issue associated with aesthetic labor is ‘objectification’ or ‘commodification of oneself’. In the aesthetic labor context, objectification is largely associated with females [59], but Holla, S. M [60]. argued that it is done by both men and women and contended that objectification is socially rooted in institutions and particular situations. Aesthetic labor is also connected with individual traits. For example, individuals who have high levels of self-esteem may be better able to cope with the demands of aesthetic labor and may perceive it as an opportunity to express their individuality and creativity. On the other hand, individuals with low self-esteem may perceive aesthetic labor as a threat to their self-concept and may experience negative outcomes, such as anxiety and stress.

Organizations shall take note of the impact aesthetic labor can have on their employees and try to create a work environment that is supportive, caring and conducting for the employee’s wellbeing. There is a need for support and resources to help employees manage their appearance and emotions, as well as ensuring that appearance standards are fair and not discriminatory on the one hand. Training managers to recognize and address the negative outcomes of aesthetic labor, such as burnout and emotional dissonance, on the other hand, could be very fruitful. Thus, we may infer that aesthetic labor can have both positive as well as negative outcomes on employees. Therefore, organizations must monitor the implications of aesthetic labor on their employees and take apt steps to mitigate its negative effects. This can play a vital role in creating a cordial and harmonious work environment, a win-win situation for both the employee as well as the employer. Social media platforms, such as Instagram and TikTok, have come as a blessing in creating a culture of constant self-presentation, both in the workplace as well as the personal space. However, at the same time, it may lead to burnout and emotional exhaustion. So, the only way out is to implement policies and practices that promote employee well-being and mental health. Additionally, organizations can promote a diverse and inclusive culture, disregarding discrimination in terms of gender, age, or race.

Academics and policymakers must broaden their understanding of “soft” skills. Specifically, they must be aware of the extent to which employers value social and aesthetic abilities [13].

CONCLUSION

Since 2012, there has been an enhanced interest of researchers in aesthetic labor, especially after 2017 (Table 2). The research interest has largely been around the emotional aspects of aesthetic labor and the relationship between gender and aesthetic labor. Most of the research on aesthetic labor has been conducted in the service industry, particularly retail. Today's aesthetics of labor research is multifaceted and evolving, as indicated by our keyword clusters. The research so far on aesthetic labor highlights the intersections of aesthetic labor with consumption, emotional demands, and gender inequalities in the retail sector. Also, discrimination challenges, emphasizing the toll of appearance-based hiring and the commodification of emotional output in the service industries, have been explored by researchers. The complexity of gender norms, such as male workers in traditionally female-oriented roles, has also been explored by researchers. Notwithstanding these insights, significant research potential lies ahead, from the interplay of aesthetic labor with personal and socio-cultural identities to its increasing impact on educational frameworks and the rapidly expanding digital domain.

The research intended to answer some important questions. The answer to these questions is as below:

Q1. What are the most influential articles on the ‘aesthetic labor’?

A study by Witz et al. [18] received the most number of citations. The publication focuses on the ways in which aesthetic labor is used by organizations to create a certain image or brand. In terms of citations, this paper is followed by a study by Warhurst and Nickson [38], which highlights the challenges faced by employees who engage in aesthetic labor in retail and hospitality and calls for greater recognition and value for this type of work.

Q2. How is the spread of research over the years?

The first paper on aesthetic labor (in the Scopus database) was published in 1980. The next paper appeared in 2000. For the early decade of the 21st century, i.e., 2000-2010, a total of 28 papers were published. From 2001-2021, 136 papers were published, indicating a growth rate of 385%. The research in said area gained momentum after 2012.

Q3. What are leading sources and countries as far as publications on ‘aesthetic labor’ are concerned?

Work, Employment, and Society is the leading source for publications in the concerned area, followed by Economic and Industrial Democracy and Gender, Work and Organization (by number of publications). The United Kingdom is the leading country for publication in the concerned areas, followed by the United States. UK and USA combined have more than 59% of total publications.

Q4. What are emerging themes in the area of ‘aesthetic labor’?

Emerging themes have been found by studying the co-occurrence of keywords.

The blue cluster focuses on aesthetic labor and its relationship to consumption, emotional labor, and gender inequality in the retail industry. Service industry workers, especially those who interact with customers, must present themselves in a certain way and manage emotions to create a positive experience, leading to stress and burnout, particularly for women. This interlinked concept highlights the need for fair appearance standards and support for employees.

The green cluster focuses on the intersectionality of discrimination in aesthetic labor, specifically related to gender and race. Appearance-based recruitment and selection practices negatively affect worker well-being and job satisfaction in service industries. The cluster also highlights the challenges faced by workers who must perform emotional and aesthetic labor, leading to emotional exhaustion and burnout. Finally, it discusses the commodification of workers and their emotions in industries that heavily rely on aesthetic labor.

The red cluster focuses on the gendered aspects of aesthetic labor, with a specific focus on male workers in traditionally feminine industries. The papers discuss how the use of physical appearance to create a brand identity can reinforce gender norms and lead to feelings of vulnerability and objectification. The cluster also examines how industries adapt to appeal to male customers and the implications of this for workers in terms of the gendered nature of aesthetic labor.

FUTURE SCOPE OF RESEARCH

How aesthetic labor intervenes with personal identity in cultural and social contexts is an important area that can be explored further. Holla, S [61]. established a relationship between the said variables, but there is not much research available in this context. Another important area to explore further is the role of sexual orientation in performing aesthetic labor. One research contends that understanding how male hairdressers negotiate their gender identities and perform heterosexual aesthetics can shed light on larger cultural expectations regarding gender and sexuality [54]. Aesthetic labor has largely been associated with the female gender, but males are also increasingly becoming part of it, especially in the modelling industry [53]. There is a need for additional research on the intersection of gender, labor, and aesthetics in the fashion industry. Although aesthetic labor has progressively demonstrated its social and economic value to the labor market, little research has been conducted on the relationship and practise of aesthetic labor in technical and vocational education. This remains an area to explore further. The education system and the significance it ascribes to aesthetic labor constitutes another subject for investigation. Another crucial area of research is to understand how aesthetic labor is perceived and performed in the context of social media, particularly photo and video-sharing platforms.

Addressing the present knowledge gaps regarding labor aesthetics could significantly expand our comprehensive understanding of the subject. By delving into how aesthetic labor intersects with personal identity and socio-cultural contexts, we can unravel the intricacies of how cultural values and personal experiences shape aesthetic labor practices. Investigating the part that sexual orientation plays, particularly with regard to male involvement in areas traditionally dominated by women, including the modelling sector, sheds light on the transformative character of gender functions and expectations within the realm of aesthetic labor. By examining the nexus of gender, work, and beauty standards, we gain a deeper insight into how society's transformations shape the fashion industry. In addition, by understanding the role of aesthetic labor in technical and vocational education, we can discern its influence on educational curriculums, potentially leading to more relevant training programs and enhanced career pathways. Finally, exploring the realm of aesthetic work in the modern digital landscape, especially on social media visual platforms, will both highlight its current relevance and predict its future path. Addressing these areas will thus deepen our comprehension of aesthetic labor, making it more comprehensive, contemporary, and contextually relevant.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE STUDY

This study is helpful in studying the evolution of research on aesthetic labor. The study presents a comprehensive review of the literature on aesthetic labor; thus, those who intend to explore the topic further can gauge a comprehensive understanding of the concept and how it has evolved over the years. This study will serve as a base on which future research on aesthetic labor can be established.

By mapping existing literature, identifying emerging themes, highlighting frequently cited works, and identifying research gaps, this paper will inspire new studies, ensuring they are based on solid foundational work while also breaking new ground. Moreover, this study explores influential authors, journals, themes and countries, allowing newer researchers to understand the landscape, connect with leaders, and identify potential collaboration opportunities. By understanding citation patterns and keyword co-occurrences, this study offers a bird's eye view of the research terrain, ensuring that upcoming studies are both innovative and contextually relevant.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

The scope of this study is limited only to publications in the Scopus database. Publications in other databases, e.g., Web of Science, can be studied to gain a deeper understanding of the area of research. Furthermore, the publications were restricted to the fields of social sciences, business, management, and accounting and psychology. The scope of research can be extended by removing these constraints. Another area that has not been explored in this study is exploring the trends in which the scholars in this field collaborate. The same can be explored by performing a co-authorship analysis. This may also uncover the benefits that such collaborations bring to the development of this field of study.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.