All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Emotional Brand Attachment, Brand Tribalism, and Co-creation in Luxury Hotels: Insights from Emerging Economies

Abstract

Introduction

In the exquisite tapestry of hospitality, luxury hotels have always concentrated on the comfort of the customer. However, the shifting shades of time unfolded the art of managing customers' emotions to strengthen hotel-customer relationships.

Methods

This trend has resulted in luxury hotels focusing on customers' value co-creation behaviour by weaving the emotions of the customers into a collaborative service symphony and ensuring that customers self-identify themselves with the luxury hotel and its other customers as a tribe. There are scant studies on the contribution of customer value co-creation behaviour towards luxury hotels; therefore, this study aimed to examine the emotional psychology of customers and their behaviour by evaluating a model curated between emotional brand attachment, brand tribalism, and customer value co-creation behaviour. Data for the study were collected by facilitating structured questionnaires to 399 Indian customers of luxury hotels. The proposed model was empirically examined by the structural equation modelling technique.

Results

The results confirmed that emotional brand attachment and brand tribalism positively affect customer value co-creation behaviour. Emotional brand attachment also positively affects brand tribalism in customers of luxury hotels. The findings offer a fresh perspective for marketers, researchers, and academicians by validating that emotions play a vital role in promoting brand tribalism and inducing value co-creation behaviour in the customers of luxury hotels. Additionally, the study validates that brand tribalism affects value co-creation behaviour.

Conclusion

This study is unique as it provides a holistic view of factors that are crucial for luxury hotels in the competitive landscape to promote a collaborative spirit of the customers, progress on relational management, and understand the emotional psychology of the customer.

1. INTRODUCTION

Various researchers are focusing intensely on the active role of customers in the service delivery process [1, 2]. The active role of customers in the business was first studied by Prahalad and Ramaswamy as a customer value co-creation process, which highlights a shift of customers from being passive customers to active participants who co-produce value with the brand [3]. The possible reasons for this focus have been explained by many studies which are related to various factors such as paradigm shift in customer expectations [4], the evolving competitive landscape of luxury hotels [5], hotels gaining ideas from their customers to serve them better [6], creating a strong foundation for customer-brand relationships [7]. In principle, research on customer value co-creation behaviour facilitates luxury businesses to recognize how to collaborate with their clients to craft extraordinary, exceptional, and profound experiences that drive faithfulness, brand advocacy, and market share [1, 2, 6]. Customers are the major source of information for the growth and development of business. Customer behaviour towards products and brands serves as the “locus of value creation” [3]. Later, the service dominant logic framework was built on this idea of co-creation, emphasizing that the value of products and services should be formed through the exchange of ideas between the buyer and seller, and not solely delivered by the seller [8, 9]. This idea originated customers as no longer simply recipients; but developed them as a critical contributor to co-create the product or service experiences [9]. Customer behaviour towards co-creation involves the customer’s contribution and participation to generate additional worth [4]. Due to this reason, research stresses the significance of studying customer behaviour in the context of value co-creation in all types of businesses related to the service industry, for example, hotels etc [9]. With the evolving role of customers, managers of hotels have accepted customers as active players over passive audiences [10]. The hospitality and tourism industry is deemed to serve customers better by making customers a part of the delivery process to find the best service experiences when comes to luxury hotels [3]. Previous study indicates a lot of scope for embarking on customer value-creation behaviour in luxury hotels [5]. In the field of consumer behaviour, practitioners persistently conceptualized consumers' value co-creation behaviour and its relationship with different constructs such as satisfaction, repurchase intentions, and brand image [11, 12]. The knowledge avenue of literature seeks further insights into how the customer value co-creation behaviour is achieved through emotional brand attachment and brand tribalism perspective in the context of luxury hotels.

In specific, the literature supports that the emotive relationship between the brand and the customer always generates customer motivation toward the brand and increases customer interaction and engagement with the brand [13]. The vast field of branding literature explores aspects like emotional brand attachment and brand tribalism. In both these concepts, customer interactions have been given space for brand promotions and development [14]. The journey of the brand-customer relationship was given utmost importance in literature. The stages of the customer-brand relationship were studied, denoting the first stage of this relationship as more utilitarian where the customer searches information about the brand for self-usage. Brand experience subsequently induces emotions leading to the second stage of congruence between the consumer’s values and the service provider’s brand. These evolved customers identify themselves with the brand, converting as member of a community shaped around the brand from individuals sharing the same values and ideas [15].

By advancing emotional brand attachment, businesses can convert clients into ardent participants and advocates, originating a convincing force for brand love and success. Emotional brand attachment has the capability of shaping up the belief system of the customer which in turn influences the perception of the customer towards their preferred brand [16]. Emotional brand attachment deals with the connection of the customer to the brand they use [17].

The aspects of brand tribalism investigate the phenomenon of consumers developing robust emotional associations with a brand, maturing into a devoted and passionate community showcasing characteristics such as community building, creating community-specific experiences, and involving customers in brand development. Brand tribalism can formulate a dedicated community of customers leading to brand advocacy and long-term success [18]. Therefore, Brand tribalism can be explained as a trait of customers that deals with customers’ priority in choosing a brand based on their culture and society. It is whispered that customers are members of different social groups and families who have the same trust and common beliefs [19]. Brand tribes are very much essential to identifying social and interpersonal experiences [20]. Existing literature observed that emotional brand attachment is needed for tribes to improve customer value creation [13, 15, 21-23].

Interestingly, despite a plethora of empirical research available on customer value co-creation behaviour, the interdependency among value co-creation behaviour, emotional brand attachment, and brand tribalism remains scant. In the previously published literature, researchers emphasized that there is an inadequate conceptualization of customer value co-creation behaviour due to lack of understanding of its key antecedents and variables leading to customer value co-creation behaviour and client’s worth to observe customer behaviour [5, 24]. Assiouras et al. [25] highlighted the need to investigate antecedents and factors affecting customer value co-creation behaviour in the hospitality industry. Another study stated the need to investigate the worth of co-creation in service-oriented industries by taking into consideration customers’ psychological [26]. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to investigate the impact of emotional brand attachment towards brand tribalism, to examine the effects of emotional brand attachment on customer value co-creation behaviour, and to examine the effects of brand tribalism on customer value co-creation behaviour in Indian customers of luxury hotels. Data indicates that the Indian luxury market is expanding. However, despite this growth, research with an exclusive focus on Indian customers of luxury remains insufficient. Many emerging markets haven't established the same level of academic attention when it comes to luxury goods and services [27]. In the present study, Indian customers were selected as respondents as the study was for luxury hotels. One of the key drivers for the Luxury hotel progress has been the growing number of customers of luxury globally, primarily in the BRICS countries, namely Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa [28]. The financial prosperity of rich people not only empowers them to invest but also indulges their fondness for luxury and opulence [29]. The choice of becoming a customer of a luxury hotel is not just transactional; rather it's experiential [30]. For these customers, staying in a luxury hotel exceeds the traditional idea of only a stay to evolve into an immersive experience and they expect the hotel to meticulously craft and cater to their expectations and pamper them on the of basis their preferences [27]. Studies suggest that customers of luxury believe in customization and personalized stays [31].

The theoretical and practical inputs of this study bridge the gap in the literature on luxury marketing by targeting Indian customers of luxury hotels. The theoretical foundation of this study lies in two theories: attachment theory [32] and the theory of social identity [33]. The Attachment Theory provides a vast scope to understand the emotional bond between the brand and the customer [32]. This is applied as a base of emotional brand attachment and Customer value co-creation behaviour. We also draw upon the Social Identity Theory as a base for relationships shown in the model between brand tribalism and customer value co-creation behaviour. The relationship between emotional attachment and brand tribalism is studied on the basis of attachment and social identity theory [34]. The development of numerous conceptualizing lenses has resulted in a pressing need to explore individual behaviour from a psychological and behavioural perspective, yielding a larger prominence to the study of human behaviour.

2. REVIEW OF LITERATURE

The literature review provides facts, summarizing all relevant studies pertaining to the constructs of the study [35, 36].

2.1. Customer Value Co-creation Behaviour

Customer value co-creation behaviour is described as the real-time participation and citizenship behaviour of the customer in the process of value formation while consuming products and services [37]. A value is a personal judgment of worth by a receiver. Co-creation is defined as the ability of articulation between an organization and customers in terms of the resources each one contributes, which helps the organization gain a competitive edge [38]. Customer involvement in value co-creation always helps to increase service delivery. Customer co-creation behaviour is categorized into two types: customer participation behaviour and customer citizenship behaviour, with each type of behaviour having four components. The elements of customer participation behaviour include information seeking, information sharing, responsible behaviour, and personal interaction, whereas the aspects of customer citizenship behaviour are feedback, advocacy, helping, and tolerance [37]. By wavering these kinds of customer behaviours positively, a firm can foster a collaborative environment of knowledge sharing with their clients to develop and offer customized products and services that lead to mutual benefits and provide an advantage to service providers and customers [25, 39, 40]. Customer’s involvement into the service delivery process improves service design and creates ease for the service provider [39]. Customer emotion is an independent variable to create customer value. Customer behaviour is a combination of psychology, social circles, and community [2]. Scholars in the hospitality industry have recommended some concepts related to psychological, community, and social circles' impact on consumer behaviour. Participation from customers is always expected in terms of information gathering, sharing, responsible behaviour, and personal interactions [37]. Citizenship behaviour of the customers also intends to help value co-creation, and service enhancements by service providers in increasing one-to-one publicity [9, 37]. Particularly in the hospitality industry, guest behaviour is always defined by engagement, service provision, and service delivery process [6]. It is also considered compulsory in worth co-creation [9, 37]. Co-creation as a dependent variable is explained as the capability of customers and companies in resource sharing that helps both the customers and service providers to get a competitive advantage [38]. These are based on feedback, advocacy, helping attitude, and tolerance [9]. Thus, emotional brand attachment and brand tribalism considerably affect customer worth co-creation performance.

In the recent past, customer value co-creation in the hospitality industry has gained a lot of interest [40, 41]. Customers depicting co-creation behaviour are of utmost value in the realm of customer behaviour in the service industry [42, 43]. Client´s co-creation actions as real-time involvement and societal behavior are important for the consumption of products and services [44]. In the present study, customer value co-creation behaviour is operationalised as the actual involvement of the customer in the value creation process of a luxury hotel and the same is evaluated from two lenses i.e., emotional brand attached and brand tribalism.

2.2. Emotional Brand Attachment

Emotional brand attachment is the connection that unites a customer to a brand characterized by feelings of affection, connection, and passion [45]. According to Berry [46], “Great brands always make an emotional connection with the intended audience. They reach beyond the purely rational and purely economic level to spark feelings of closeness, affection, and trust.” In the present research, the three dimensions of emotional brand attachments are studied namely, affection, passion, and connection [16]. Affection refers to a consumer's emotional state of peace, love, and affability towards a brand. Connection mirrors the feeling of being emotionally involved with a brand, whereas passion denotes feelings such as consumer amusement and attraction to a brand [45].

A lot of research and discussion have been undertaken in the past to support that customer emotions encourage customers to select specific products and services [16, 17]. A study states that the emotions of the customers towards the brand change from time to time. Attachments towards a brand is a gradual process [47]. The hospitality industry and hotels as bands are highly emotive because of increased customer expectations [48]. Customer expectations of luxury hotels are superiority, originality, relaxation, sophistication, and exclusivity [49]. Luxury hotels must deliver to encourage the emotive expectations of the guests beyond room accommodation [48]. Customers' emotions have been studied in connection with repurchase intention and satisfaction [50], customer engagement [51], brand loyalty [22], and word of mouth [52]. Based on the available review mentioned above, it has been found that customer emotions are changing during the course, and customer actions are based on the emotional attachment that the customer has towards the service provider. Hotels should provide the best facilities beyond providing boarding and lodging to encourage emotional attachments. Many researchers have studied the function of emotional brand addition towards brand tribalism and client worth co-creation behaviour.

2.3. Brand Tribalism

Brand tribalism is the inclination of people to make choices based on their communal beliefs about brands. Followers of a brand tribe are not merely consumers who use a brand; they also support, promote and advocate the brand. Brand tribalism analyses the strength of a brand's relationship with the customer [53]. The scale of Brand tribalism is based on five main dimensions namely, the degree to fit with lifestyle (the suitability of the brand with the image, personality and life of the customer), passion in life (how much the brand resonates with the desire of the customer), reference group acceptance (the extent of which the brand will be accepted by the social circle, community or a tribe of a customer), social visibility (the social presence or identity of the brand in the circle of the customer), and collective memory (the brand reminds the customer of his social circle) [52].

In the present study, brand tribalism is operationalized as the influence of the social network of the customer on their choice of a luxury hotel and is conceptualized as a consequence of emotional brand attachment and an important antecedent of customer value co-creation behaviour. Brand tribalism is explained as an important concept for the service industry because it helps firms to establish long-lasting relations with their customers and their tribes [15]. Customers who belong to tribal communities are observed as active co-creators in value creation because they customize offerings in the market. Brands that offer unique values to tribes induce a sense of ownership or power in the customer that leads to the customer's citizenship behaviour [22]. Brand tribalism is studied in research related to luxury cruises [22], luxury brands [54], luxury cars [55, 56], and luxury housing market [57]. This indicates that brand tribalism has been linked with luxury services due to niche communities using self-expressive brands. Emotional attachment to the brand lays a base for brand tribalism. Customers of shared and customized consumption yield a behaviour of value creation with the service provider they patronize. It is observed from the above that customers of different groups possess different characteristics and service providers should always focus on those things to get utmost satisfaction from them. This model provides insights into psychological mechanisms that suggest that individuals make emotional ties with the brand, leading to feelings of inclusion and identification with the brand tribes. This study empirically supported that emotional bond or emotional attachment is an essential variable that affects tribes and customer value co-creation [21, 22, 13, 15, 23].

2.4. Theoretical Framework

This study includes two existing theories on consumer emotions and behaviour towards luxury brands. The first theory used is the Attachment theory, which is one of the most consequential perspectives in behavioural sciences [58]. Managerially, attachment theory provides a base for marketers to evaluate the relationship between a brand and its customers and how this kind of relationship can provide positive business results [59]. In the area of Marketing research, numerous studies have perceived consumers’ attachment towards brands from an emotive and interpersonal viewpoint to seek loyalty, market share, and positive behaviour [60-62]. For a luxury product, attachment between luxury brands and customers is the strength. This concept was pragmatically used for the study of consumer research and tourism [15].

This study also draws upon the Social Identity Theory. Social identity theory was projected in social psychology by Tajfel and his contemporaries. Social Identity Theory was instigated with the foundation that people outline their own personalities based on the social group they belong to, and such outlines work to safeguard and bolster their self-identity [33]. In such a scenario, group member develops an outlook that can be divided into two categories; one is a category of one’s group i.e. “in-group”, and the other is fostered on the other groups i.e. “out-group”. This also leads to a tendency to view one’s group with a superior bias via the out-group [63]. This process of favoring one´s in-group occurs in three stages: social categorization, social identification, and social comparison [9]. Social identity represents that the conduct and self-concepts of individuals are based on their association with a social group. When human beings self-identify themselves with a group or a brand, they tend to adapt and sculpt their attitudes, emotions, and behaviour according to group norms or brand norms [33]. In marketing research, it was concluded that consumer or brand tribes function as small or subgroups defined through their identifiable collective familiarities, feelings, and realities [64].

2.5. Conceptualisation and Hypotheses Development

It is essential to conceptualize the constructs by recognizing the earlier efforts of scholars. Keeping that in consideration, the researchers tried to operationalize the sub-dimensions of customer value co-creation behaviour, emotional brand attachment, and brand tribalism. This shall also form the foundation of hypothesis development.

2.6. Emotional Brand Attachment and Brand Tribalism

Customers are not confined to being individuals but often belong to social circles, communities, or tribes [65]. Customers belonging to a tribe can be characterized as loyal, enthusiastic advocates of brands and can lead to innovation and creativity [66, 53]. Sierra et al. [67] highlighted the psychological process explaining emotional attachment as a base for the establishment of tribalism. Ali et al. [68] supported that emotionally attached customers of the same brand tend to group themselves due to their comfort zone of using the same brand. These people embrace the same brand product or service and are recognized as communities or tribes. Positive connotations towards the same brand are the primary reason for forming these tribes. Brand tribes are incredibly supportive of their members. They are knitted with shared social and personal values and experiences derived from their emotional connection and relationship with the brand [67]. The current study proposes that if the customers' emotions are well looked after by a luxury hotel, it may lead them to act as a community or a tribe for a luxury hotel. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H1. Emotional brand attachment leads to brand tribalism in the customers of luxury hotels.

2.7. Emotional Brand Attachment and Customer Value Co-creation Behaviour

Brands that work around the emotional attachment to their customers leave lasting and favourable impacts and impressions on customers and elicit customer feedback [50]. According to the source attractiveness model, “source attractiveness affects the effectiveness of communication between service staff and customers”. Attachment is an essential and profound aspect of the source attractiveness model [69], which affects the perception and behaviour of the customer and can lead to changes in the customer’s viewpoint, stance and mindset, thereby strengthening the interactional relationships in the tourism industry [70]. The positive influence of customers’ emotions on their citizenship behaviour was studied, exploring the relationship between customers’ attachment to the brand and customer citizenship behaviour in the hospitality industry in Taiwan [23]. To improve and endorse customer value co-creation behaviour, we suggest emotional brand attachment plays a prominent role as a predictor of this process. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H2. Emotional brand attachment positively affects customer value co-creation behaviour in the customers of luxury hotels.

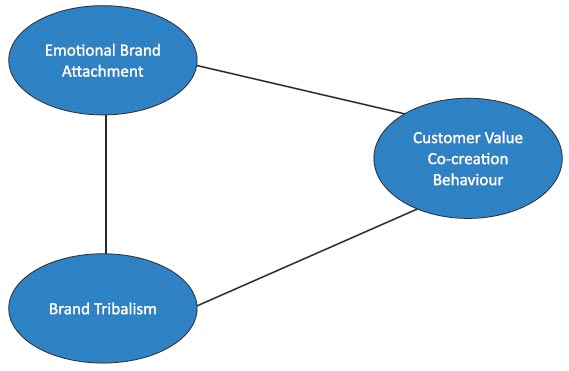

Conceptual model.

2.8. Brand Tribalism and Customer Value Co-creation Behaviour

This fact is not hidden from anyone that consumers consume together as a group or tribe and provides a platform for value co-creation [19]. Consumers play a diverse role in a brand’s promotion. This role could be a consumption role and sometimes a co-creation role to help organizations sell their products further to other customers [71]. Literature on value co-creation demonstrates how customer–producer interface, collaboration, exchange of ideas, and participation play a critical role in the value co-creation process [3]. Veloutsou and Black [19], studied the roles of brand tribe members and concluded that consumers consume together as a group or tribe and provide a platform for value co-creation. Therefore, this study proposed the following hypothesis:

H3. Brand tribalism positively affects customer value co-creation behaviour in the customers of luxury hotels.

The theoretical model proposed is based on the research hypothesis expressed in Fig. (1).

3. METHODOLOGY

3.1. Measures/Instrument Development

The survey approach was followed with the help of a structured questionnaire. The questionnaire was classified under four sections: the first section in the questionnaire collected the demographic details of the respondents, the second section focused on emotional brand attachment towards luxury hotels, the third section focused on brand tribalism, and the fourth section covered customer value co-creation behaviour of luxury hotels. To measure the constructs, three existing scales were used after modifying them for suitability. A total of eight experts from Industry and five from academic institutes were chosen for the instrument development panel to review the question- naire. This study employed a 7-item scale of “emotional brand attachment” proposed by Dwivedi et al. [16]. To bring novelty to this scale, a new item in this scale was added “I like to act like a brand ambassador of this hotel in public”. The words of a few items were altered to make it more relevant for Indian respondents. The second scale employed was a 16-item scale of “brand tribalism” proposed by Veloutsou and Moutinho [53]. This scale was modified and finalized with 14 items, and two items were deleted. The third scale employed was 29 items “customer value co-creation behaviour scale” of Roy et al. [5]. This scale was recommended by Yi and Gong [37] and was used previously in the hospitality industry [38]. This scale was modified and finalized with 18 items to rationalize the survey, ensuring it remained succinct and focused on assembling relevant and meaningful data. The original items and finalized items along with major references are also tabulated in Table 1.

The vocabulary and the sequence of the items evaluating these three constructs were altered in order to control the “order bias” [72]. Additionally, the confiden- tiality and anonymity of data was assured to the participants. The items were marked on a five-point Likert scale from 1 as “strongly disagree” to 5 as “strongly agree”.

| Construct / Code | Original Items | No. of Items after Alteration of Scale | Major Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Brand Attachment (EBA) | 7 | 8 | Dwivedi, Johnson, Wilkie, and De Araujo-Gil, (2019) |

| Brand Tribalism (BT) | 16 | 14 | Veloutsou and Moutinho, (2009) |

| Customer value co-creation behaviour (CVCB9) | 29 | 18 | Roy,Balaji, Soutar, and Jiang, (2020) |

3.2. Data Collection

The data were collected through online and offline modes between May 2022 to August 2023 from 399 Indian customers of luxury. The pre-testing of the questionnaire was done among 71 Indian customers of luxury to gain insights before the final data collection. As the population of the luxury consumer is not defined, snowball and purposive sampling techniques were used to collect the data. 460 responses were collected, out of which, 61 responses were deleted due to missing data. The descriptive analysis of the respondents is derived from the dataset tabulated in Table 2.

50.9% of respondents belonged to the age group of 40-50 years, 25.81% were between 29-39 years, 19.5% were of 51 years and 3.8% belonged to the age group of 18-28 years. The majority of the respondents 71.9% were married. Males (69.4%) outnumbered females being 28.8%. A sum of 37.3% of respondents had annual income between 25L to 50L, 26.1% between 50L to 1Cr, 15.5% between 1Cr to 1.5 Cr, 11.5% above 2Cr and 9.5% between 1.5Cr to 2Cr. The general picture of our sample can be depicted as a mix of young and experienced customers who either visit luxury hotels for vacation/ leisure, or are working for private organizations, are self-employed, and are good samples to study emotions, tribalism, value co-creation behaviour. The features of the current study samples were similar to the samples in related studies on tourism [73].

4. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

4.1. Data Analysis

To analyze the data, exploratory factor analysis was executed using IBM SPSS. After extracting the factors, confirmatory factor analysis was checked using IBM AMOS to acquire the reliability and validity of the existing factors [74]. Based on the hypothesized model, the proposed relationships between emotional brand attachment, brand tribalism and customer value co-creation behaviour were measured by employing the structural equation modeling.

| Demographic | Frequency | % | Demographic | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Profile | - | - | Profile | - | - |

| Age (Years) | - | - | Education | - | - |

| 18-28 | 15 | 3.8 | Higher School | 12 | 3.0 |

| 29-39 | 103 | 25.8 | Graduate | 160 | 40.1 |

| 40-50 | 203 | 50.9 | Post Graduate | 189 | 47.4 |

| 51 years & above | 78 | 19.5 | Doctoral | 16 | 4.0 |

| Gender | - | - | Others | 22 | 5.5 |

| Female | 115 | 28.8 | Profession | - | - |

| Male | 277 | 69.4 | Govt. Employee | 6 | 1.5 |

| Others | 5 | 1.3 | Private Sector | 179 | 44.9 |

| Do not disclose | 2 | 0.5 | Self-employed | 173 | 43.4 |

| Marital Status | - | - | Retired | 7 | 1.8 |

| Single | 86 | 21.6 | Others | 33 | 8.3 |

| Married | 287 | 71.9 | Annual Income | - | - |

| Do not disclose | 26 | 6.5 | 25L-50L | 149.0 | 37.3 |

| - | - | - | 50 L- 1Cr | 104.0 | 26.1 |

| - | - | - | 1 Cr - 1.5 Cr | 62.0 | 15.5 |

| - | - | - | 1.5Cr - 2 Cr | 38.0 | 9.5 |

4.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

The researcher should choose the embodied variables in a measurement model based on the results of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) in order to have scientifically explained results of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Therefore, an EFA was employed with the help of using maximum likelihood as an extraction method based on eigenvalues greater than one [75-78]. Maximum likelihood was selected to identify discrepancies among items. It offers the goodness of fit test for factor solution [79] apart from being consistent with the succeeding measurement model.

A principal components analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was applied to produce a stable and replicable factor analysis [80]. Prior to the extraction of factors, the suitability of exploratory factor analysis was tested by assessing the values of “Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity”. Results for KMO for EBA are 0.748, BT is 0.840 and CVCB is 0.839 as indicated in Table 3. This indicates that the sample is adequate for EBA, BT and CVCB. Bartlett test was conducted to examine the hypothesis, and the result concluded that the variables do not relate to one another to run a successful and meaningful EFA as EBA, BT and CVCB; all three are shown as Sig <0.05.

EFA sorted 8 statements of EBA (EBA1 to EBA8) into three overlapping original clusters namely “Passion”, “Connection” and “Affection”. A new item explored through the current study being “EBA8: I like to act like a brand ambassador of this hotel in public” was loaded and grouped under “Connection”. This EFA yielded three factors same as the original factors namely passion, connection, and affection with 83.025 Cumulative %. Out of 14 items in the original scale of BT, EFA yielded four factors viz., “Reference group acceptance”, “Social Visibility of Brand”, “Degree of fit with lifestyle” and, “Passion in Life”. The lowest BT14, originally conceptualized as “Collective Memory” had no strong loading (0.489), this item is eliminated. After removing one item (BT14) factor analysis on 13 items under four factors. The EFA yielded four factors same as the original aforementioned factors with 74.868 cumulative %. Out of 18 items in the original pool of CVCB, the EFA yielded six factors viz., “Information sharing & Personal Interaction”, “Responsible behaviour”, “Feedback”, “Tolerance” “Information seeking”, and “Advocacy & Helping”. A new item explored in this study was “CVCB18: I defended the hotel when I heard from other guests about the lack of service” fell under the tolerance factor CVCB. The EFA yielded six factors with 77.752 cumulative %. Thus, six components were effective enough in representing all the characteristics or components highlighted by the stated variables.

4.3. Common Method Bias

The current study used a single method to connect data at the same time for all constructs. Thus, a “common method bias” test was employed to determine whether the results of the measurement model were impacted by a method bias [81]. To measure the presence of “common method bias” in the present study, Harman single-factor test was used [80]. The single factor so generated showed a variance of 43.10% lower than the 50% total variance of the scale. This implied the absence of common method bias.

4.4. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

EFA identified the structure of factors, whereas the CFA backed the factor structure extracted through EFA [75]. To make sure that every parameter could measure the construct, confirmatory factor analysis was deployed to check the fitness of the measuring model [75]. The factor loadings were significant for all items being >.50 as shown in Table 4. Before testing the model, there must be no reliability and validity concerns. All CR>0.70, hence we can conclude that this model has achieved composite reliability. All AVE>0.50, hence model has achieved convergent validity. The measurement value of CR and AVE as shown in Table 5, confirms convergent validity [82]. The outcomes of the CFA demonstrate satisfactory model fit values. According to Hair et al. [83] to ensure discriminant validity, two situations should be fulfilled. The first one is that the maximum shared variance should be lower than AVE, and the second is that the square root of AVE should surpass the inter-construct correlations. As shown in Table 6, MSV measures are lower than AVE, and the square root of AVE is greater than inter-construct correlations. Therefore, conditions are satisfied, and discriminant validity is ensured. All constructs are more strongly correlated with their items compared to other construct’s items.

| - | KMO and Bartlett's Test | EBA | BT | CVCB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling | .748 | .840 | .839 | ||

| Adequacy. | - | - | - | - | - |

| Bartlett's Test of | Approx. Chi-Square | 1855.656 | 3408.804 | 3802.922 | |

| Df | 28 | 91 | 153 | ||

| Sphericity | - | ||||

| - | Sig. | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | |

| Construct | Indicators and Relative items | Standardized Factor Loadings |

|---|---|---|

| EmotionalBrand | EBA1 I feel I love this luxury hotel | 0.86 |

| EBA2 My sentiments towards luxury hotel can be characterised by | 0.87 | |

| Attachment (EBA) | Affection | |

| EBA3 My sentiments towards this luxury hotel is featured by sense of | 0.90 | |

| individual relation (e.g. memories/experiences) | ||

| EBA4 I feel attached to this luxury hotel | 0.81 | |

| EBA5 I am passionate about this luxury hotel | 0.85 | |

| EBA6 I feel proud to be a customer of this luxury hotel | 0.86 | |

| EBA7 I feel mesmerised by this luxury hotel | 0.92 | |

| EBA8 I like to act like a brand ambassador of this hotel in public | 0.74 | |

| BrandTribalism(BT) | BT1 This luxury hotel is right for my personality | 0.80 |

| BT2 Visiting this luxury hotel helps me network with likeminded people | 0.72 | |

| BT3 This luxury hotel is related to the way I perceive life | 0.81 | |

| BT4 This luxury hotel helps increase my pride | 0.64 | |

| BT5 More about this luxury hotel that goes above its physical features | 0.85 | |

| BT6 I prefer to go to luxury hotel as I am confident that my relatives and | 0.84 | |

| well wishers approve of it | ||

| BT7 I am grateful to this luxury hotel as my associates use it | 0.92 | |

| BT8 Both me and my well wishers like to stay because of liking with | 0.93 | |

| each other | ||

| BT9 I feel sense of possessiveness by going to the luxury hotel with my | 0.94 | |

| Friends | ||

| BT10 I often discuss with my social network about this luxury hotel | 0.82 | |

| BT11 Everywhere luxury hotel brand is available | 0.69 | |

| BT12 to my knowledge luxury hotels have so many customers | 0.92 | |

| BT13 I know that people feel good about visiting this luxury hotel | 0.74 | |

| CustomerValue Co-creation | CVCB1 I have asked others for information on what this luxury hotel | 0.76 |

| Offers | ||

| CVCB2 I checked other behaviour towards luxury hotel services | 0.93 | |

| Behaviour(CVCB) | CVCB3 I shared my preference with the hotel employee while making | 0.81 |

| my reservation | ||

| CVCB4 Suggestions and feedback is given from time to time to improve | 0.89 | |

| Services | ||

| CVCB5 Given reply to all functional queries of hotel staff | 0.85 | |

| CVCB6 I fulfil duties as guest of the hotel | 0.82 | |

| CVCB7 I adequately completed all the expected behaviours (e.g. was | 0.85 | |

| not loud, didn’t disturb other guests, etc) | ||

| CVCB8 I helped the hotel to get more clients in the past | 0.79 | |

| CVCB9 I accept the terms and conditions of luxury hotel | 0.79 | |

| CVCB10 I was very much friendly to the staff | 0.78 | |

| CVCB1I recommend useful ideas I believe to the hotel staff know | 0.82 | |

| CVCB12 If I get good service I appraise them | 0.90 | |

| CVCB13 If I get a problem I will let the hotel staff know it | 0.70 | |

| CVCB14 I suggest friends and relatives to make use of hotel service | 0.72 | |

| CVCB15 I encourage and support other customers too | 0.75 | |

| CVCB16I am patient to rectify and suggest the hotel staff mistakes | 0.76 | |

| CVCB17 I never mind to wait in queue during long hours | 0.84 | |

| CVCB18 I defended the hotel when I heard from other guests about the | 0.81 | |

| lack of service |

| EBA & CVCB Dimensions | Items | CR | AVE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information seeking | - | - | 2 | 0.841 | 0.727 | ||||

| Passion | - | - | - | 3 | 0.908 | 0.767 | |||

| Connection | - | - | - | 3 | 0.861 | 0.675 | |||

| Affection | - | - | - | 2 | 0.854 | 0.745 | |||

| Information | sharing personal inter | 4 | 0.902 | 0.697 | |||||

| Respondents behaviour | 4 | 0.885 | 0.658 | ||||||

| Feedback | - | - | - | 3 | 0.847 | 0.651 | |||

| Tolerate | - | - | - | 3 | 0.845 | 0.646 | |||

| Advocacy helping | - | - | 2 | 0.701 | 0.540 | ||||

| BT & CVCB Dimensions | Items | CR | AVE | ||||||

| Information | seeking | - | - | 2 | 0.836 | 0.719 | |||

| Reference group | - | - | 5 | 0.951 | 0.794 | ||||

| Social | visibility | - | - | 3 | 0.830 | 0.623 | |||

| Degree of fit | - | - | 3 | 0.820 | 0.604 | ||||

| Passion in life | - | - | 2 | 0.717 | 0.563 | ||||

| Advocacy helping | - | - | 2 | 0.704 | 0.544 | ||||

| Respondents behaviour | - | 4 | 0.885 | 0.658 | |||||

| Feedback | - | - | - | 3 | 0.847 | 0.651 | |||

| Tolerate | - | - | - | 3 | 0.845 | 0.646 | |||

| Information sharing Personal Interest | 4 | 0.902 | 0.697 | ||||||

| EBA & BT Dimensions | Items | CR | AVE | ||||||

| Degree of fit | - | - | - | 3 | 0.820 | 0.604 | |||

| Passion | - | - | - | 3 | 0.908 | 0.766 | |||

| Social Visibility | - | - | 3 | 0.830 | 0.623 | ||||

| Connection | - | - | - | 3 | 0.861 | 0.675 | |||

| Affection | - | - | - | 2 | 0.853 | 0.744 | |||

| Reference group | - | - | 5 | 0.951 | 0.794 | ||||

| Passion_in_life | - | - | 2 | 0.720 | 0.567 | ||||

4.5. Structural Equation Modeling

The relationships mentioned in the hypotheses were measured using IBM AMOS. The results of the model fit demonstrated good model fit with CMIN/DF = 1.925; GFI = 0.903; CFI = 0.953; and RMSEA = 0.048 [84]. The outcomes of the structural model revealed that emotional brand attachment leads to brand tribalism in the customers of luxury hotels. Therefore, H1 is supported. The results of the model fit demonstrated good model fit with CMIN/DF = 1.938; GFI = 0.905; CFI = 0.983; and RMSEA = 0.046 [84]. The outcomes of the structural model (table 7) revealed that emotional brand attachment positively affects customer value co-creation behaviour in the customers of luxury hotels. Therefore, H2 is supported. The results of the model fit demonstrated good model fit with CMIN/DF = 2.035; GFI = 0.985; CFI = 0.939; and RMSEA = 0.051 [84]. The outcomes of the structural model revealed that emotional brand attachment positively affects customer value co-creation behaviour in the customers of luxury hotels. Therefore, H3 is supported. H1 suggested that Emotional brand attachment leads to brand tribalism in the customers of luxury hotels. This hypothesis is validated (β = 0.643; p-value < 0.001). H2 suggested that Emotional brand attachment positively affects customer value co-creation behaviour in the customers of luxury hotels. This was also confirmed (β =0.738; p-value < 0.001). H3 suggested that Brand tribalism positively affects customer value co-creation behaviour in the customers of luxury hotels. This was also confirmed (β = 0.660; p-value < 0.001).

Table 6.

| EBA and BT | MSV | MaxR(H) | Degree_of_Fit | Passion | Social_Visibility | Connection | Affection |

Reference _Group |

Passion_in_ Life |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree_of_fit | 0.071 | 0.825 | 0.777 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Passion | 0.117 | 0.914 | 0.190 | 0.875 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Social_visibility | 0.183 | 0.884 | 0.267 | 0.236 | 0.789 | - | - | - | - |

| Connection | 0.194 | 0.883 | 0.153 | 0.342 | 0.128 | 0.821 | - | - | - |

| Affection | 0.194 | 0.853 | 0.168 | 0.322 | 0.307 | 0.441 | 0.863 | - | - |

| Reference_group | 0.183 | 0.960 | 0.137 | 0.212 | 0.428 | 0.105 | 0.104 | 0.891 | - |

| Passion_in_life | 0.005 | 0.771 | -0.069 | -0.038 | 0.038 | -0.037 | -0.054 | 0.051 | 0.753 |

| EBA and CVCB | MSV | MaxR(H) | Info_seeking | Passion | Connection | Affection |

Inf_sharing__ personal_inter |

Resp_behaviour | Feedback | Tolerate |

Advocacy__ Helping |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Info_seeking | 0.102 | 0.889 | 0.853 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Passion | 0.119 | 0.914 | 0.133 | 0.876 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Connection | 0.193 | 0.879 | 0.235 | 0.345 | 0.821 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Affection | 0.193 | 0.856 | 0.193 | 0.323 | 0.439 | 0.863 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Inf_sharing__personal_inter | 0.204 | 0.909 | 0.311 | 0.277 | 0.233 | 0.400 | 0.835 | - | - | - | - |

| Resp_behaviour | 0.268 | 0.887 | 0.182 | 0.152 | 0.106 | 0.152 | 0.366 | 0.811 | - | - | - |

| Feedback | 0.204 | 0.875 | 0.185 | 0.127 | 0.199 | 0.181 | 0.452 | 0.267 | 0.807 | - | - |

| Tolerate | 0.268 | 0.850 | 0.223 | 0.196 | 0.273 | 0.233 | 0.388 | 0.518 | 0.260 | 0.804 | - |

| Advocacy__helping | 0.213 | 0.703 | 0.320 | 0.197 | 0.231 | 0.241 | 0.265 | 0.371 | 0.241 | 0.461 | 0.735 |

| BT and CVCB | MSV | MaxR(H) |

Info_ seeking |

Reference_ _group |

Social_ _visibility |

Degree_ of_fit |

Passion_ in__life |

Advocacy_ _helping |

Resp_ _behaviour |

Feedback | Tolerate |

Inf_sharing_ _Personal_Int |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Info_seeking | 0.103 | 0.858 | 0.848 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Reference__group | 0.185 | 0.960 | 0.261 | 0.891 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Social__visibility | 0.208 | 0.880 | 0.249 | 0.430 | 0.789 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Degree_of_fit | 0.075 | 0.825 | 0.209 | 0.137 | 0.269 | 0.777 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Passion_in__life | 0.018 | 0.758 | 0.111 | 0.051 | 0.039 | -0.071 | 0.750 | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Advocacy__helping | 0.213 | 0.714 | 0.316 | 0.086 | 0.235 | 0.274 | -0.070 | 0.738 | - | - | - | - | |

| Resp__behaviour | 0.267 | 0.887 | 0.189 | 0.182 | 0.261 | 0.194 | 0.011 | 0.366 | 0.811 | - | - | - | |

| Feedback | 0.204 | 0.878 | 0.186 | 0.028 | 0.103 | 0.166 | 0.070 | 0.229 | 0.266 | 0.807 | - | - | |

| Tolerate | 0.267 | 0.851 | 0.231 | 0.246 | 0.456 | 0.239 | -0.077 | 0.462 | 0.517 | 0.257 | 0.804 | - | |

| Inf_sharing__Personal_Int | 0.204 | 0.909 | 0.321 | 0.196 | 0.348 | 0.175 | 0.136 | 0.259 | 0.366 | 0.452 | 0.389 | 0.835 | |

Table 7.

| Path Relationships | Estimate (β) | P-value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Customer_Value__Cocreation__Behaviour<--- Emotional__Brand__Attachment | 0.738 | *** | Supported |

| H2: customer__value__cocreation__behaviour<--- Brand__tribalism | 0.660 | *** | Supported |

| H3: Brand__Tribalism<--- Emotional_Brand__Attachment | 0.643 | *** | Supported |

Note: All path estimates are standardized.

**p < 0.001.

4.5. Theoretical Implications

The findings of this study contribute to the literature in the field of hospitality and tourism. The results confirm that emotional brand attachment and brand tribalism were key antecedent variables for customer value co-creation behaviour in luxury hotels. The current research used two theories for the model i.e. attachment theory and social-identity theory. Attachment theory underlines the importance of emotive connections to protect relationships. In the context of marketing, consumer behaviour, and branding, attachment theory suggests that customers can form emotional connections with brands, parallel to attachments in human relationships. The social identity theory states that customers self-identify themselves with a brand socially when they believe that the brand is socially accepted in their “in group”. In the proposed model, emotional brand attachment leads to brand tribalism and emotional brand attachment and brand tribalism, both lead to customer value co-creation behaviour in customers of luxury hotels. Emotionally attached customers like to proactively show customer value co-creation behaviour because emotionally invested customers have a soft corner for the brand and therefore, they like to co-produce with the brands. This progression is underlined by the attachment theory. Emotionally attached customers like to self-identify themselves with the brand due to the emotional connection they have with the brand. This soft corner also makes the customer accept the brand in their tribe “in-group”. This progression is supported by attachment theory and social identity theory. Brand tribalism leads to customer value co-creation behaviour because when a customer perceives the brand to be an “in group” brand, customers are comfortable advocating the brand. This progression is supported by social identity theory.

The model suggests that the emotional connection is established through attachment theory and the commonality of social identity theory. Both these, together contribute to the progress of emotional brand attachment, brand tribalism, and customer value co-creation behaviour. Assimilating these theoretical frameworks into the model studied in the current study not only augments our understanding of consumer behaviour but also clarifies strategic acumens for luxury hotels aiming to foster brand loyalty, community engagement, and positive customer interactions.

4.6. Practical Implications

The model studied in the study also provides practical implications for the marketers and managers of Luxury hotels. Practically, Luxury hotels can innovate emotionally resonant brand experiences to foster attachment. By empathizing with customers' emotional needs and aspirations, luxury hotels can customize their branding strategies to induce positive emotions. This might entail storytelling, customised engagements, and compassionate customer service, all intended to construct strong emotional ties and associations between the luxury hotel and the consumer. Previous literature on the emotional brand attachment scale was limited to emotions such as “love, attachment, sentiments”. In the study, a new item was added “I like to act as a brand ambassador of this hotel in public” which also depicts the vulnerable aspect of emotions the hotels can work upon.

Social Identity Theory stresses the worth of group identity. In the practical boundaries, luxury hotels must create and nurture offline and online communities via networking events and curating social media groups where customers with similar interests can be given networking platforms for interactions. These podiums allow customers to direct their identity and position themselves on the brand positioning, fostering a sense of belonging and social validation. Luxury hotels must keep these groups as close-knit social groups and should facilitate discussions, spread privileged information and exclusive content about the brand, and encourage user-generated content within these communities, establishing social identity aspects. Dedicating and devoting various identities and preferences within the customer base is crucial. By leveraging data analytics and customer segmentation, luxury hotels can tailor their marketing strategies. Customised communication, product endorsements, and proposals based on each customer’s preferences improve the sense of reciprocity. Customers potentially like to engage positively when they get the feeling that the brand understands their exact needs and desires. Luxury hotels can encourage their customers to give suggestions and feedback because this kind of co-creation gives opportunities to customers to showcase their creativity which encourages a sense of ownership to customers and a luxury hotel will gain new ideas which are guest-friendly. This will serve as a powerful endorsement. When consumers observe that the luxury hotel aligns with their thought processes, they are more likely to harness an emotive relationship with the luxury hotel. Moreover, luxury hotels can engage in social exchange by sharing a part of their profits to charitable causes, depicting their commitment towards social responsibility, and reinforcing positive reciprocity. This can be done by a luxury hotel by doing organic farming within the landscape promoting waste management and contributing to the SDG goals.

By incorporating the aforementioned practical implications into the marketing strategies, luxury hotels can not only foster robust emotional connections, positive exchange of value for co-creation, and social identity among their esteemed customers but also stimulate positive behavioural intentions, leading to market share and abstain customers to shift to another brand and sustained growth.

4.7. Limitations and Future Research

Firstly, this study used a sample of Indian customers, therefore, it might lead to cultural or geographical constraints. These results might not be fully applied to other regions or countries. Future researchers are suggested to apply the same model for researching different nationality customers of luxury hotels. Secondly, the responses of the customers might be self-reported. In the future, researchers are suggested to conduct a study to strengthen the causal inferences of the results by using two questionnaires. The first questionnaire would contain questions on customer’s perceptions and feelings regarding their preferred luxury hotel. The second questionnaire, which would mainly contain questions related to the value co-creation behaviours of the customer could be distributed to the luxury hotel manager. Thirdly, this study did not focus on the effects of any mediating variable, or moderating variables, consequently, future studies should investigate the mediating effects of other customer-brand relationship variables. Finally, this study focused on how emotional brand attachment and brand tribalism affected customer value co-creation variables but did not study the behavioural intentions of the customer. Future researchers could expand this model by studying the effects of customer value co-creation behaviour on the intentions of the customer or moderating the role of other variables in these relationships like social media, etc.

CONCLUSION

This study makes new contributions to luxury hotel marketing and customer behaviour boundaries. Firstly, the current research has introduced a very critical aspect of customer value co-creation behaviour from two lenses and concluded emotional brand attachment and brand tribalism as antecedents of customer value co-creation behaviour in the realm of luxury hospitality. In fact, emotional brand attachment has been concluded as an antecedent of brand tribalism as well. The study determines that the psychological mechanism of emotionally invested customers of luxury hotels makes the customer see the luxury hotel as an extension of their personality, which leads to a positive outcome for luxury hotels and customers. Emotionally connected customers like to contribute to the success of the hotel by depicting proactive behaviours like partaking in activities conducted by the hotel, and the service delivery process. These customers also believe that the hotel is always striving to ensure their comfort and like to act as citizens of the hotel and become its defenders and promoters.

Secondly, the current study offers insights into hoteliers, managers and marketers of luxury hotels to re-look at the measures to enhance the emotional experience for their customers and formation of more intensive engagements. The result of this study validated the “congruence” and “resonance” stages of customer-brand relationships. Customer brand relationship has three stages; the first is utilitarian, which means the customer collects information about the brand for self-usage. The second stage is congruence, in this stage, an emotionally connected customer tends to self-identify with the brand, leading to connections with other customers who like the same brand. This is validated by the results of this study that an emotionally attached customer depicts brand tribalism. Therefore it can be concluded that if the emotions of the customers are looked after well, it can make the customer join the brand community or a tribe for a hotel. The third stage is “resonance” which is validated by seeing brand tribalism's positive effects on customer value co-creation. In this stage, emotionally attached customers become active members of a tribe, having an emotional agreement with the group and get involved in the creation of the brand and its values. The result of the study illuminated that emotional brand attachment positively affected customer value co-creation behavior, which means positive emotions like love, and sentiments of customers towards their preferred luxury hotel can positively affect the value co-creation behaviour of customers. The present results are also in agreement with the previous studies [7, 50, 85, 86]. The study confirmed that emotional brand attachment precursors brand tribalism, which has also been confirmed in another study [87].

Thirdly, in the Indian context, the need for research in this field is crucial, because of the increased purchasing power of Indian citizens who are the customers of luxury in India. This study will also contribute to the knowledge of international luxury hotels should they plan to capture Indian customers of luxury hotels.

Fourthly, the result of this study also confirmed the source attractiveness model [69], depicting attachment as an essential aspect that affects behaviour of the customer in Luxury hotels. The study revealed that customers who are emotionally attached to a brand are willing to help luxury hotels co-create the service and are also willing to help other customers of the same brand. These results validated the emotional attachment theory [32].

Lastly, this study highlights the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) 2015. According to SDG 3: there is a need to have good health and well-being practices, and SDG 12 promotes responsible consumption and production. Previous studies have revealed that customers like to choose a destination where they have an ease of having medical care in case of crisis [88]. This fact proves that travellers look up to places of stay where their well-being is not in danger. Along similar lines, luxury hotels believe in ensuring positive emotions for customers. The concept of emotional brand attachment stems deep inside SDG 3 as emotional brand attachment arises from positive experiences a customer may have during their stay in a luxury hotel. The luxury hotel environment is supposed to offer relaxation which enhances the connection of guests with the hotel by ensuring comfort, which significantly reduces stress and aligns with SDG 3. During the recent pandemic of COVID-19, luxury hotels played a pivotal role which further strengthened the emotions of customers towards luxury hotels. Additionally, the spa treatments, fitness centers and healthy organic dining experiences at luxury hotels ensure the physical well-being of a customer and a healthier lifestyle. Hotels become a home away from home leading to comfort and positive emotional experiences, which have a direct impact on mental health, fostering a sense of belonging and emotional well-being. Brand tribalism leads to positive memories and social bonds of customers, and these memories contribute to overall life satisfaction and social well-being, especially when shared with family and friends. The positive effect of working and strategizing around emotional brand attachment that positively affects brand tribalism, assures a positive impact on guest well-being and aligns with SDG 3, contributing to the global efforts to promote good health and well-being for all.

Likewise, customer value co-creation behaviour can contribute significantly to Sustainable Development Goal 12 in various ways. Hotels can reduce waste, conserve water and energy, and promote sustainable practices to minimize their environmental impact. Implementing eco-friendly policies and encouraging guests to participate in sustainable practices contribute to responsible consumption and production. By engaging customers in the co-creation process, luxury hotels can gain valuable insights, ideas, and feedback, leading to sustainable consumption and co-production. Co-creation allows hotels to tailor products and services based on customer needs and preferences. By co-designing products with customers, hotels can create more efficient, sustainable, and user-friendly solutions. By encouraging environmentally friendly innovations, waste reduction, and energy efficiency, co-creation initiatives support sustainable industrialization and infrastructure development as outlined in SDG 12.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTIONS

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to itssubmission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| EFA | = Exploratory factor analysis |

| CFA | = Confirmatory factor analysis |

| PCA | = Principal components analysis |

| KMO | = Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin |

| SDG | = Sustainable Development Goals |

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all participants to ensure their voluntary participation in this study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.