All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Being Mindful to Achieve Person-Organisation Fit and Community Fit: Moderating Role of Isolation

Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to investigate the relationship between mindfulness among employees and their person-organisation fit, incorporating self-compassion theory and job embeddedness theory. Additionally, the study explores the mediating role of community fit and the moderating impact of workplace isolation on this relationship.

Background

In today's organizational landscape, mindfulness practices are prevalent. Despite evidence of positive outcomes for individual employees, the linkage between mindfulness and Person-Organisation fit (P-O fit) remains underexplored. This study addresses this gap, examining the intricate relationships among mindfulness, community fit, isolation, and P-O fit.

Methods

In this study, we have looked at the mediating effect of community fit between mindfulness and person-organisation fit, and the moderating role of isolation among the same using multiple regression and PROCESS macro. The data were collected from 153 Indian employees working in manufacturing industries in various roles.

Results

Findings have revealed a positive association between mindfulness and person-organisation fit. Community fit has been found to emerge as a significant mediator, and the study has identified the moderating effect of workplace isolation on the established connection between mindfulness and P-O fit.

Conclusion

This research study enriches the literature on mindfulness and P-O fit, emphasizing practical implications for human resource practitioners to use mindfulness as an effective HRM intervention, which can foster positive organizational outcomes.

1. INTRODUCTION

Employee retention is a critical challenge faced by organizations worldwide, exacerbated by issues, such as job satisfaction, recruitment problems, and overall employee engagement. High turnover rates lead to increased recruitment costs, loss of organizational knowledge, and disruptions in team dynamics, ultimately affecting overall productivity and performance. One promising area of exploration to address these issues is the role of mindfulness in the workplace.

“What is happening around me?” is the idea that employees today should focus on having an awareness of their job, organisation, and community to maintain themselves in the social relationships in and around work. Such awareness can be rendered as being mindful. “Mindfulness means paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally” [1], which is usually explicated by academicians via mindfulness theory. Mindfulness has been defined as “intentionally paying attention to present-moment experience (physical sensations, perceptions, affective states, thoughts, and imagery) in a nonjudgmental way, thereby cultivating a stable and nonreactive awareness” [2, 3]. “Mindfulness in the context of self-compassion means that one is aware of the present moment experience of suffering along with perspective and balance for those suffering” [4]. This balanced and non-judgmental awareness can foster a deeper understanding of oneself and others, thereby promoting awareness of organizational values and practices, in the context of employees, which should be crucial in establishing P-O fit.

Imputing mindfulness at the workplace, defined as attributing mindfulness qualities or practices within organizational contexts, has been confirmed as a fruitful Human Resource Management (HRM) intervention directed toward various positive individual outcomes. For example, when the Human Resource (HR) manager of the organisation adopts mindfulness practices, employees enjoy job satisfaction [5], and exhibit higher work engagement [6], outstanding task performance [7], improved well-being [8], remarkable Organisational Citizenship Behaviour (OCB) [9], and better stress management [10]. Nonetheless, limited understanding exists about how mindfulness affects individuals’ fit into their organisations or community or how well individuals connect with others despite the propositions made by the researcher [11] regarding the positive effect of mindfulness on workplace relationships. A person-organisation fit is a degree to which employees find their values, beliefs, and characteristics compatible with their organisations [12]. Thus, to comprehend the role of mindfulness in organisations or communities, it is better to focus on the role mindfulness plays in the job embeddedness theory. Job embeddedness theory suggests that there are some factors that influence the retention of employees at workplace, such as fit to organisation, community, sacrifice, and links. The importance of such study even increases considering the other side benefits employees may gain in their work-life along with improved social relationships once they start imputing mindfulness in practice.

Ample research papers have emphasized job embeddedness by investigating the role of positive psychological variables, such as justice [13] and interactional fairness [14], which elaborate our understanding of how imputing such positive individual constructs assists in attaining Person-organisation fit (P-O fit). This also displays that existing literature lacks in considering the highly positive construct, like mindfulness, to predict P-O fit.

This study includes three focal points. Firstly, squaring with the model of person-organisation fit [15], mindfulness theory [16], and job embeddedness theory [17], we suggest that mindfulness positively associates with the person-organisation fit. Person-organisation fit (P-O fit) denotes the synchronization between an employee’s values and their organisation’s values [18]. Implementing mindfulness helps individuals to be conscious of their surroundings (i.e., consequences of their behaviour, their peers, their teams or groups, their community, and their organisations) in the exact moment [19-21]. Consequently, employees are also aware of their organisations and feel connected to their organisations, leading to improved P-O fit [22].

Secondly, considering the model of person-organisation fit [15], we elucidate the meaning of community fit associating mindfulness with P-O fit by explaining its mediating role. Community fit is described as an employee’s seeming congruence with the community or society where he/she resides [17]. We contend that mindfulness interventions, such as mindfulness meditation and mindfulness workshops, enhance awareness of social norms and values, HR, and behavioural practices between practitioners and employees, facilitating community fit and P-O fit. Although mindfulness positively impacts both community fit and P-O fit, we have considered community fit as a mediator between mindfulness and P-O fit, because the effect on P-O fit is rather indirect as it has been observed earlier by researchers that community fit might lead to P-O fit [23, 24]. Consequently, we recommend that community fit plays a mediating role between mindfulness and P-O fit.

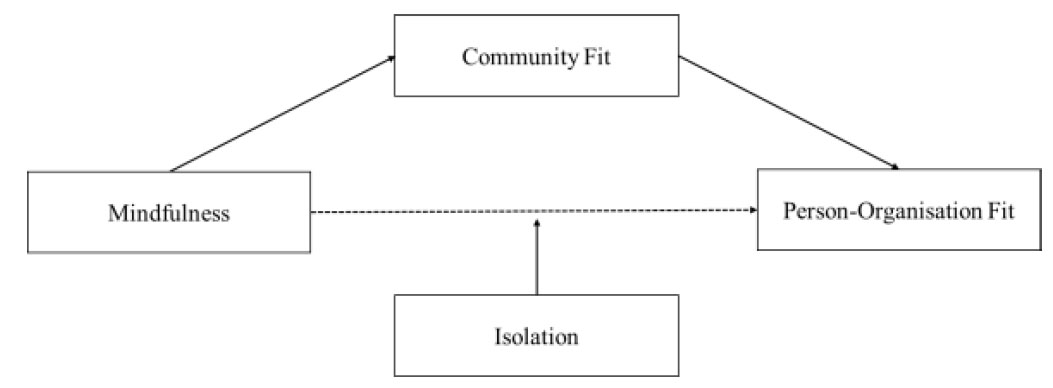

Lastly, we examine the moderating effects on the relationship between mindfulness and P-O fit, specifically identifying situations where mindfulness has either a strong or weak association with community fit or P-O fit. Mindfulness can be said to be embedded in the self-compassion theory [25-27], which states that one should relate to his/her sufferings as part of common human experience and should treat oneself with kindness while maintaining a sense of awareness about the environment [4]. Thus, one’s association with the environment is a crucial factor to be taken into consideration and if one feels disassociated with their environment, it should affect their P-O fit. This study contends that isolation has a moderating association between mindfulness and P-O fit. Isolation in the HR context is one of the manifestations of work alienation, which “refers to a sense of estrangement and an absence of social support or meaningful social connection in the workplace” [28-30]. “Social isolation has been recognized as a major risk factor for morbidity and mortality in humans for more than a quarter of a century” [31]. Thus, it can be implied that isolation could aggravate the P-O fit of employees, tumbling the effect of awareness of values and consciousness for the organisation [32]. So, we have proposed and tested if intense isolation may deteriorate the direct association between mindfulness and P-O fit (Fig. 1).

This study was needed, as nowadays, employees find it challenging to get embedded in their organisations and their respective communities, and they feel somewhat isolated, especially in the context of the pandemic. Thus, mindfulness practices can play the role of torch-bearer in these challenging times, making employees more embedded in their communities and their organisations. The study also suggests avoiding isolation as it instigates the decline of employee fit in the organisation and suggests mindfulness as a measure to cope with isolation.

Theoretical model of the study.

2. MINDFULNESS AND PERSON-ORGANISATION FIT

Recent studies have underscored the role of mindfulness in promoting psychological well-being among employees. For instance, a recent study [33] demonstrated that mindfulness, mediated by psychological hardiness and moderated by workload, helped university employees cope with emotional exhaustion during the COVID-19 crisis. This highlights the critical role of mindfulness in maintaining psychological resilience and reducing burnout in high-stress environments, thereby having a positive impact on the organisation fit of employees.

Additionally, another study [34] found trait mindfulness to positively influence cross-cultural sales performance by reducing perceived cultural distance. This study has provided valuable insights into how mindfulness can enhance intercultural competence and effectiveness in diverse work settings. Mindfulness enables employees to better manage cultural differences, leading to more successful interactions of values in globalized business environments. In the realm of entrepreneurship too, the interaction effect of goal orientation and mindfulness on firm innovation capability has been observed by researchers [35], concluding mindfulness to significantly enhance the firm’s performance. The research has demonstrated mindfulness to not only benefit individual employees, but also foster a culture of innovation and continuous improvement within organizations.

The construct Person-organisation fit (or P-O fit) is expressed as “the compatibility between people and organisations that occurs when: (a) at least one entity provides what the other needs, or (b) they share similar fundamental characteristics, or (c) both” [12]. While this definition includes transactional exchanges, such as an employer providing monetary compensation to meet an employee's financial needs, it is important to recognize that P-O fit encompasses more than just these basic needs. The expanded explanation of this definition focuses on two essential notions of P-O fit: “supplementary fit and complementary fit”. Supplementary fit denotes the resemblance of essential features of employees and organisations, indicating shared values and cultural alignment. In contrast, complementary fit denotes the state where organisations and employees accompany one another or “when a person’s characteristics make whole the environment or add to it what is missing” [12].

Also, the idea of P-O fit can said to be deeply rooted in value congruence, which, in a broader sense, reflects the degree to which an individual’s values are synchronized with their environment [36-38], whereas in the organizational context, it reflects the degree to which an employee’s values are in equilibrium with the values occurring at their workplace [12, 39]. Comprehensive assessments of P-O fit measure both subjective perceptions of fit and objective indicators of alignment between personal and organizational values, ensuring a thorough evaluation of P-O fit beyond mere transactional needs. As suggested by Chatman [15], the P‐O fit of employees could be more significant when the employee’s values are compatible with those of the organisation. Accordingly, value congruence becomes essential to be considered to attain the person-organisation fit. Now, to attain congruence of values, it is firstly important for the individuals to be aware of their own and the organisational values, for which, it is a must for the employees to be mindful of themselves and their workplaces, sinces values are something implicit rather explicit, and observed by being mindful. Since, this idea has not been explored empirically, it becomes even more important and relevant to look up the P-O fit from a fresh perspective of an individual’s eye by considering awareness about oneself and one’s surroundings as a factor that could lead to P-O fit.

Moreover, the concept of P-O fit is directly associated with work engagement [39] and HR practitioners have commenced recognizing mindfulness as a norm for employee engagement in the work society. Individuals having elevated P-O fit are expected to classify themselves according to their organisations and develop high engagement [40]. Or we can say, that in case employees have high engagement, they are inclined to perform their duties and obligations allocated by their organisation [41]. In addition, it has been observed that mindfulness is associated with work engagement and makes the employees effectively engaged in their work [6]. Thus, we suggest the following hypothesis:

H1 Mindfulness is positively associated with person-organisation fit.

3. COMMUNITY FIT AS MEDIATOR

The job embeddedness theory has identified two aspects of being embedded “on the job and off the job” [42], and has classified these dimensions into three facets: fit, sacrifice, and links [17, 43]. “On the job and off the job” dimensions have been classified as organisational and community dimensions by some scholars [23, 44, 45]. “The organisation is where the individual works and the community is defined as the town, city, or suburb where the individual resides” [44]. Thus, “organisational embeddedness consists of work‐related influences, whereas community embeddedness encompasses aspects from community lives, and together, they keep individuals in these respective locations” [23, 46, 47]. Community fit is the manifestation of community embeddedness and focuses primarily on how human relations work around the organisations to make employees feel connected to society.

“Community fit is the extent to which individuals’ needs and interests are congruent with the community’s environment” [48-50]. Similar to P-O fit, correspondence of values to community is a must for the individuals to have so that the degree of an individual’s values is synchronized with their environment [38], i.e. community fit. Thus, to attain the person-organisation fit, it becomes essential for individuals to be aware of the organisational values and other aspects, making the value of awareness and consciousness necessary for attaining community fit and consequently establishing the link between mindfulness and P-O fit. A new branch of mindfulness practice has emerged in recent times considering the impact of being mindful on the social relations of the practitioner, i.e., social mindfulness, means considering the requirements and benefits of peers in a way that honours the idea that most people like to choose for themselves and, thus, we suggest the below hypothesis:

H2: Mindfulness is positively associated with community fit.

As already discussed earlier, the association between community fit and P-O fit has been previously tested by researchers, and a positive effect of community fit has been observed on the organisational fit of the employees [23]. Taken together with H2, we predict that employees are more likely to build more vital community fit, when employees are mindful or when organisations adopt mindfulness interventions, which eventually improves person-organisation fit. Therefore, we formulate the following hypothesis:

H3: Community fit is a mediator in the association between mindfulness and person-organisation fit.

4. THE MODERATING ROLE OF ISOLATION

Person-organisation fit has been associated with work alienation [51]. “Alienation” is denoted as a failure to communicate one’s feelings, exhaustion towards the job, and having a sense of isolation or discordancy with organisational culture values [51, 52]. Moreover, work alienation has been studied to play a moderating role along with P-O fit and other constructs [53]. Additionally, literature on socialisation has proposed that communicating organisational fit values supports employees’ entry and maintaining ideal relations. This concept suggests that organisation fit generates the spirit of belongingness, while misfits may provoke a sense of loneliness or isolation [54]. It is also noticeable that both loneliness and isolation have an impact on the turnover intentions of employees [55].

To emphasise the relationship between isolation and mindfulness, several studies have discovered the relationship between mindfulness and isolation [56]. Also, few studies have revealed that a sense of isolation activates ample mental prejudices and interpretive alterations [57, 58], so it may be presumed that isolation can affect mindfulness [59]. Hence, we have determined that isolation could moderate the association between mindfulness and person-organisation fit. Thus, we suggest the below hypothesis:

H4: Isolation moderates the positive relationship amid mindfulness and P-O fit in a way that association is weaker when isolation is higher.

The final model (Fig. 1) suggests that community fit plays a mediating role in the association between the state of being mindful and attaining P-O fit. Also, the direct relation is moderated by isolation as hypothesised in H4. Thus, integrating both mediation and moderation effects in one model, we suggest the following hypothesis:

H5: Isolation moderates the direct relationship between mindfulness and P-O fit in the mediation model where community fit is a mediator.

5. METHODS

5.1. Sample and Procedure

Data were gathered through a sample of 153 full-time working employees in Indian manufacturing organisations. We selected organisations having more than 1 billion Indian rupees (as per the current market rate, 12.5 million US dollars approx.) of turnover and sent questionnaires to 850 employees working in such organisations. We received 153 responses out of 850 requests sent (18% response rate), and no response was missing any information as all questions were mandatory in the Google form sent to respondents via email, so no response was dropped during the filtering of data. Out of 153 respondents, 61.4% were male and 39.6% were female. These organisations were majorly located in the northern parts of India and belonged to both the public (33.3%) and private sectors (66.7%). Although only 1.3% of respondents described themselves as having a low education level, 20.3% held a bachelor’s degree, whereas 56.9% had a master’s degree, and 21.6% had a doctoral qualification, thus assuring the sample to be sturdily concentrated on exceedingly qualified personnel. Further, 74% of respondents served as middle and high-level employees, attracting our attention towards highly qualified employees even more. 56% of respondents had job experience of fewer than ten years, 29% had job experience of ten to twenty years, whereas only 15% of respondents were highly experienced employees. Furthermore, the experience of respondents was according to their age as a large part of respondents (63%) were aged 21 to 35 years, a few (26%) were aged 21 to 35 years, and very few (11%) were aged more than 50 years. In addition, 58% of employees were not married and 40.5% were married, whereas 1.5% of respondents had another marital status. Also, we measured the income level of respondents in three categories: 39% had income less than 5,00,000 Indian Rupees (approximately 6000 dollars) per annum, 27% had an income from 5,00,000 to 10,00,000 Indian Rs. (approximately between 6000 dollars and 12000 dollars) per annum, and 34% had an income of more than 10,00,000 Indian Rs. (approximately 12000 dollars) per annum.

The respondents were promised concealment and anonymity of their participation in the study. We applied a cross-sectional study design to avoid common method bias, which may occur in cross-sectional studies; various tests suggested earlier [60] were checked to ensure the absence of common method bias.

5.2. Measures

Table 1 includes the factor loadings of items belonging to variables accompanied by their AVE (Average Variance Extracted) and composite reliability.

5.2.1. Community Fit

To measure community fit, we used a five-item subscale from the job embeddedness scale [17] involving a 7-point Likert scale with “1” depicting “very untrue for me” and “7” depicting “very true for me”. As discussed, job embeddedness involves two aspects: organisation-related and community-related, and these two dimensions are then classified into three facets: dimensions-fit, sacrifice, and links. One of the sample items was “This community I live in is a good match for me”. The reliability was α =0.88.

| Variables and Items | Standardised Factor Loading | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mindfulness | ||||

| Keeping emotions in a balanced perspective | 0.697 | - | - | - |

| Taking a balanced view of this painful situation | 0.806 | - | - | - |

| Keeping things in perspective | 0.567 | - | - | - |

| Isolation | ||||

| Separating and cutting off from the rest of the world | - | 0.801 | - | - |

| Struggling more than others | - | 0.514 | - | - |

| Feeling all alone | - | 0.859 | - | - |

| Community fit | ||||

| Love for community | - | - | 0.821 | - |

| Family-oriented environment | - | - | 0.900 | - |

| Suitable match | - | - | 0.879 | - |

| Thinking of community as home | - | - | 0.888 | - |

| Leisure activities (e.g., sports, outdoors, cultural, arts) | - | - | 0.675 | - |

| Person-organisation fit | ||||

| Utilisation of skills and talents | - | - | - | 0.808 |

| Match for organisation | - | - | - | 0.899 |

| Valued personally by organisation | - | - | - | 0.890 |

| Customised work schedule | - | - | - | 0.714 |

| Fit with organisation’s culture | - | - | - | 0.891 |

| Authority and responsibility at the organisation | - | - | - | 0.862 |

| - | - | - | - | - |

| Average variance extracted | 0.486 | 0.548 | 0.697 | 0.717 |

| Composite reliability | 0.735 | 0.777 | 0.919 | 0.938 |

5.2.2. Person-organisation Fit

To measure person-organisation fit, we used another six-item subscale also from the job embeddedness scale [17] involving a 7-point Likert scale with “1” depicting “very untrue for me” and “7” depicting “very true for me”. One of the sample items was “I fit with my organisation’s culture”. The Cronbach alpha was α =0.91.

5.2.3. Mindfulness

To measure mindfulness, we used a three-item subscale from the State Self-Compassion Scale - Long-form (SSCS-L) developed earlier [4] involving a 7-point Likert scale with “1” depicting “very untrue for me” and “7” depicting “very true for me”. We asked the respondents to think of any painful situation they are going through, either any challenge or inadequacy they feel, and respond to the questions according to the feeling they have for themselves in such a situation. The sample item was “I am taking a balanced view of this painful situation.” The alpha coefficient was α =0.65

5.2.4. Isolation

To measure isolation, we used another three-item subscale also from the State Self-Compassion Scale - Long-form (SSCS-L) developed earlier [4] involving a 7-point Likert scale with “1” depicting “very untrue for me” and “7” depicting “very true for me”. We asked the respondents to think of any painful situation they are going through, either any challenge or inadequacy they feel, and respond to the questions according to the feeling they have for themselves in such a situation. A sample item was “I am feeling all alone right now”. The internal consistency was α =0.73.

5.2.5. Control Variables

As discussed in the sample frame of the study, we measured some variables regarding the demographical traits of the samples, and then they were controlled on an individual level, which could have affected person-organisation fit. We controlled for person-organisation fit with two dummy variables: gender (1 = female, 0 = male) and organisation status (1= private, 0= public). We also controlled for six discrete variables: age (0= less than 21 years, 1= 21 to 35 years, 2= 36 to 50 years, and 3= more than 50 years), marital status (0 = married, 1 = unmarried, 2= other), job position (0= junior level, 1=middle level, 2=senior level), education (0= diploma, 1= graduate, 2= postgraduate, 3= PhD), salary [0 = less than 5,00,000 INR. per annum (approximately 6000 dollars), 1= 5,00,000 to 10,00,000 INR. (approximately between 6000 dollars and 12000 dollars) per annum, 2= more than 10,00,000 INR. per annum (approximately 12000 dollars)], and total work experience (0=less than 10 years, 1=10 to 20 years, 2= more than 20 years). It is noticeable that the reported results showed a similar pattern when these variables were not controlled.

5.3. Analytical Strategy

Multiple regression and the process model [61] were applied to test the hypotheses. In addition, the overall proposed model was tested using PROCESS macro with bootstrapping, i.e., promptly used in research of the behavioural sciences domain [62-65]. Particularly, while analysing H1 and H2, we applied multiple regressions, and while examining H3, H4, and H5, 5,000 bootstrap samples were formed using SPSS and PROCESS macro [61] by random sample technique with the possibility of reselection from the sample of 153 respondents. First, a 95% confidence interval was computed for the projected outcome using bootstrapped results. Afterward, we checked whether zero was within the 95% confidence interval of bootstrapped samples or not; when zero is amid the confidence interval, the projected outcome is empirically acceptable.

6. RESULTS

Before examining any hypothesis, we conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to test the measurement model, which included all the variables of interest: mindfulness, isolation, person-organisation fit, and community fit. The purpose of CFA is to ensure that the survey items are correctly loaded onto their respective constructs. The results presented that the model where all the items were loaded to their respective constructs [χ2 (113) = 124.728, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.026, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.980, Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.976, Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) = 0.993, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) = 0.055] provided a better fit compared to the model that combined all items into a single latent variable, i.e., a single factor model [χ2 (119) = 782.367, RMSEA = 0.192, CFI = 0.949, TLI = 0.808, GFI= 0.957, SRMR=0.117]. This indicates that each construct was distinct. Appendix Table 1 provides a detailed breakdown of these results.

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics and the correlation scores among the variables of focus and controlled variables. Person-organisation fit was positively correlated with mindfulness (r = 0.457, p < 0.01) and community fit (r = 0.604, p < .01). Mindfulness has been found to have a positive correlation with community fit (r = 0.392, p < 0.01). It is worth mentioning that mindfulness was not associated with isolation (r = 0.035, p > 0.05), signifying the distinction between the two constructs affecting the person-organisation fit. Apart from the major correlation observed, there were a few observations related to the controlled variable, which we have considered important to discuss. We observed age to be positively correlated with mindfulness (r = 0.160, p < 0.05), suggesting that older employees might have higher levels of mindfulness. Similarly, isolation was negatively correlated with age (r = -0.258, p <0.01), indicating older employees to have lesser feelings of isolation. Another interesting yet somewhat obvious finding was that married employees felt less isolated than those who were unmarried or divorced (r = 0.205, p <0.05). Further, job positions showed a significant negative correlation with isolation (r = -0.208, p < 0.01), indicating higher job positions to be associated with lower levels of isolation. Also, isolation was negatively correlated with salary (r = -0.167, p < 0.05) and work experience (r = -0.290, p < 0.01). Moreover, the type of organisation (public and private) also affected the fit of employees such that employees fit better in private organisations (r = 0.285, p < 0.01). These findings suggest that demographic factors and job characteristics can significantly influence key constructs and merit further exploration beyond being mere control variables.

| - | - | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mindfulness | 5.29 | 1.05 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||||||||||

| 2 | Isolation | 3.52 | 1.68 | 0.035 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||||||

| 3 | Community fit | 5.60 | 1.24 | 0.392 | ** | -0.157 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||||||||

| 4 | Person-organisation fit | 5.59 | 1.24 | 0.457 | ** | -0.158 | - | 0.604 | ** | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||||

| 5 | Gender | 0.39 | 0.49 | -0.097 | - | 0.121 | - | -0.012 | - | 0.036 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||||||

| 6 | Age | 1.48 | 0.69 | 0.160 | * | -0.258 | ** | 0.134 | - | 0.144 | - | -0.179 | * | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||||

| 7 | Marital status | 0.43 | 0.52 | -0.026 | - | 0.205 | * | -0.099 | - | -0.115 | - | 0.143 | - | -0.393 | ** | - | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

| 8 | Job position | 0.99 | 0.72 | 0.064 | - | -0.208 | ** | 0.143 | - | 0.136 | - | -0.192 | * | 0.586 | ** | -0.442 | ** | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| 9 | Education | 1.99 | 0.69 | -0.016 | - | -0.057 | - | 0.060 | - | 0.025 | - | 0.250 | ** | 0.027 | - | -0.112 | - | 0.026 | - | - | - | - | - | |||

| 10 | Salary | 0.95 | 0.86 | 0.017 | - | -0.167 | * | -0.027 | - | -0.029 | - | -0.297 | ** | 0.488 | ** | -0.508 | ** | 0.471 | ** | 0.077 | - | - | - | - | ||

| 11 | Organisation status | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.149 | - | -0.027 | - | 0.285 | ** | 0.161 | * | 0.076 | - | 0.087 | - | 0.027 | - | 0.104 | - | 0.047 | - | -0.108 | - | - | - | |

| 12 | Total work experience | 0.59 | 0.74 | 0.105 | - | -0.290 | ** | 0.087 | - | 0.065 | - | -0.159 | - | 0.814 | ** | -0.474 | ** | 0.636 | ** | 0.028 | - | 0.558 | ** | 0.019 | - | - |

| Model (D.V.) |

Model 1: Person-organisation Fit |

Model 2: Community Fit |

Model 3: Person-organisation Fit |

Model 4: Person-organisation Fit |

Model 5: Person-organisation Fit |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | B | SE | |||||

| Constant | 2.489 | - | 0.601 | 2.858 | - | 0.612 | 1.094 | - | 0.562 | 5.255 | - | 0.416 | 2.898 | - | 0.516 |

| Gender | 0.219 | - | 0.202 | -0.010 | - | 0.206 | 0.223 | - | 0.176 | 0.267 | - | 0.197 | 0.252 | - | 0.174 |

| Age | 0.279 | - | 0.229 | 0.097 | - | 0.234 | 0.232 | - | 0.200 | 0.262 | - | 0.223 | 0.226 | - | 0.197 |

| Marital status | -0.335 | - | 0.209 | -0.246 | - | 0.213 | -0.215 | - | 0.183 | -0.266 | - | 0.204 | -0.172 | - | 0.181 |

| Job position | 0.236 | - | 0.170 | 0.185 | - | 0.173 | 0.146 | - | 0.148 | 0.193 | - | 0.167 | 0.113 | - | 0.147 |

| Education | -0.004 | - | 0.136 | 0.093 | - | 0.139 | -0.050 | - | 0.119 | 0.007 | - | 0.134 | -0.032 | - | 0.118 |

| Salary | -0.162 | - | 0.140 | -0.167 | - | 0.143 | -0.081 | - | 0.123 | -0.144 | - | 0.138 | -0.048 | - | 0.122 |

| Organisation status | 0.147 | - | 0.196 | 0.540 | ** | 0.200 | -0.117 | - | 0.175 | 0.093 | - | 0.192 | -0.146 | - | 0.173 |

| Experience | -0.312 | - | 0.232 | -0.088 | - | 0.236 | -0.269 | - | 0.202 | -0.349 | - | 0.227 | -0.286 | - | 0.201 |

| Mindfulness | 0.523 | *** | 0.088 | 0.416 | *** | 0.089 | 0.320 | *** | 0.082 | 0.584 | *** | 0.088 | 0.379 | *** | 0.084 |

| Community fit | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.488 | *** | 0.071 | - | - | - | 0.462 | *** | 0.071 |

| Isolation | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | -0.158 | ** | 0.056 | -0.102 | * | 0.050 |

| Mindfulness x isolation | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.093 | * | 0.045 | 0.081 | * | 0.040 |

| R | 0.512 | - | - | 0.481 | - | - | 0.481 | - | - | 0.557 | - | - | 0.481 | - | - |

| R Square | 0.262 | - | - | 0.231 | - | - | 0.231 | - | - | 0.310 | - | - | 0.231 | - | - |

| F-test | 5.633 | *** | - | 4.782 | *** | - | 4.782 | *** | - | 5.770 | *** | - | 4.782 | *** | - |

| Model | Estimate | 95% CI. | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | t | p | Lower | Upper | ||

| Mediation model (H3) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Direct effect | 0.320 | 0.082 | 5.958 | 0.000 | 0.158 | 0.482 | |

| Indirect effect | 0.203 | 0.074 | - | - | 0.069 | 0.351 | |

| Moderation model (H4) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Weak isolation | 0.428 | 0.102 | 4.214 | 0.000 | 0.227 | 0.629 | |

| Strong isolation | 0.741 | 0.130 | 5.711 | 0.000 | 0.485 | 0.998 | |

| Mediation model and moderation (H5) | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| Direct effect via weak moderation | 0.244 | 0.094 | 2.600 | 0.010 | 0.058 | 0.429 | |

| Direct effect via strong moderation | 0.514 | 0.120 | 4.302 | 0.000 | 0.278 | 0.751 | |

Afterward, all hypotheses were tested and presented as different models in Table 3. Hypothesis 1 suggested a positive association between mindfulness and person-organisation fit, and so did the findings of model 1, which expressed that mindfulness is positively associated with the person-organisation fit [B (unstandardized regression coefficient) =0.523, β (standardised regression coefficient) = 0.441, p < 0.001], accounting for control variables.

Hypothesis 2 suggested a positive association between mindfulness and community fit, and so did the findings of model 2, expressing mindfulness to be positively associated with community fit (B=0.416, β = 0.351, p < 0.001). Accordingly, both hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2 were supported.

Hypothesis 3 predicted the mediating effect of the community fit on the positive mindfulness and person-organisation fit. We used PROCESS macro number 4 in SPSS [61] to get the findings of model 3 (simple mediation model) in this study. In model 3, while the direct effect of mindfulness on person-organisation fit decreased (B = 0.32, β= 0.27, p < 0.001), community fit showed a positive association with P-O fit (B = 0.488, β=0.487, p < 0.001). The bootstrapping results in Table 4 show a significant direct relationship between mindfulness and person-organisation fit (95% C.I.= 0.158, 0.482) and the indirect relationship between mindfulness and community fit (95% C.I. = 0.069, 0.351). Therefore, hypothesis 3 was supported.

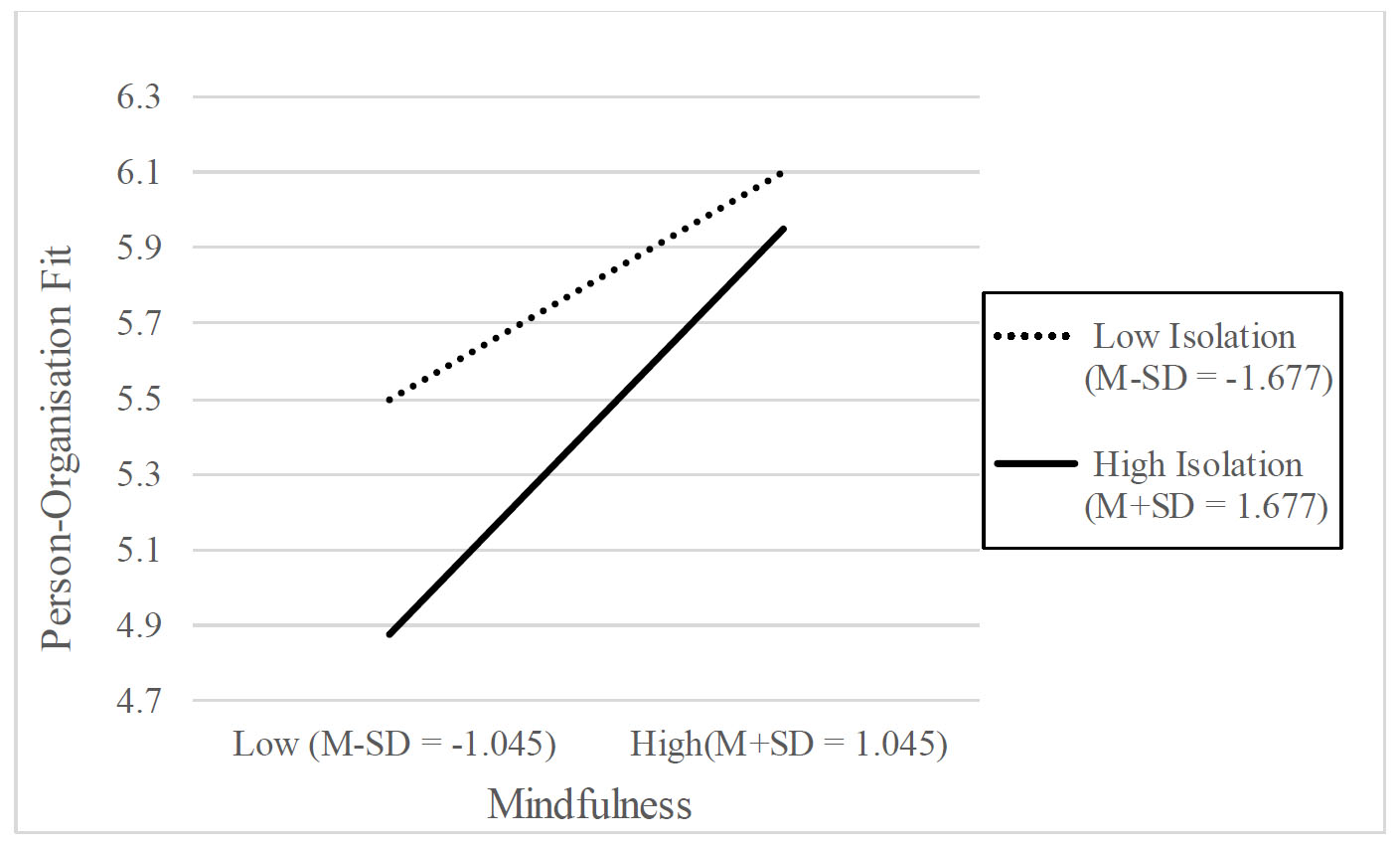

Hypothesis 4 projected that isolation has a moderating effect on the association between mindfulness and person-organisation fit. Therefore, we verified hypothesis 4 with PROCESS macro number 1 (moderation model) [61], and the results are reported in model 4. Also, we formulated the same model through regression by adding an interaction variable “mindfulness x isolation” into the dataset. The result depicted that isolation has a negative association (B = -0.158, p < .01) with the person-organisation fit. Secondly, the interaction variable was significant (B = 0.93, p < .05), demonstrating isolation to moderate the positive association between mindfulness and person-organisation fit, and that isolation has a role to play in the relationship between mindfulness and P-O fit. Furthermore, the bootstrapping outcomes in Table 4 depict that in those instances when isolation was low, the moderating effect was significant but low (C.I. 95%= 0.227, 0.629), and in other instances when isolation was high, the moderating effect was significant as well as high (C.I. 95% = 0.485, 0.998). Notably, since the interaction effect was significant consequently, hypothesis 4 was supported.

Interaction effect of mindfulness and isolation on person-organisation fit.

Overall, we verified hypothesis 5 employing the entire model 5 using PROCESS macro number 5 (conditional mediation model, moderation in direct effects) [61], following the method by [66]. We discovered evidence of a significant conditional direct effect among mindfulness and person-organisation fit, both when isolation was low (B=0.244, 95% C.I. = 0.058, 0.429) and when the isolation was high (B=0.514, 95% C.I. = 0.278, 0.751). Moreover, to ensure the absence of any common method bias, a separate single latent factor was added to the model (i.e., common method factor), and the consequent model also showed a significant relationship among the constructs [60].

Considering the previous findings [66, 67], the interaction effect was plotted (Fig. 2) to understand the moderation effect visually. The effect of mindfulness on the person-organisation fit was studied using two situations: one when isolation is high (mean plus one standard deviation) and the second situation when isolation is low (mean minus one standard deviation).

7. DISCUSSION

We accumulated data from 153 employees to test our hypotheses. Our sample consisted of young, mid-, and senior-level employees with an 18% response rate. The demographic composition and response rate of our sample may have implications for the generalizability of our findings. While the diversity in job levels provides a broad perspective, the relatively low response rate may introduce response bias. Future research should aim for higher response rates to ensure the findings are representative of the broader population. Additionally, targeted efforts to engage a more varied age demographic group could help to further validate the findings across different employee groups.

Our findings have justified all the hypotheses. This study has displayed a positive association between mindfulness and person-organisation fit through community fit, whereas the direct association between mindfulness and P-O fit has been found to be moderated by isolation. For mindfulness to be effective in organisations, employees need to channel their mindfulness into generating positive sentiments and resources to create a high level of work engagement, as also established by previous research studies [68-71].

The association established among community fit and P-O fit in the current study has been found to be in line with prior research [23] that has established a similar result. Similarly, the effect of isolation as a moderator has aligned with previous studies [56], establishing an association between mindfulness and isolation; similarly, Damar and Çelik [51] have established an association between isolation and P-O fit through the concept of alienation.

Mindfulness not only guides individual employees to fit into their community, but also mitigates the adverse effects of isolation. Our results have shown isolation to have a direct negative effect on P-O fit, but this adverse effect has been found to be reduced when mindfulness was considered. Thus, HR practitioners may use mindfulness practices as part of HRM intervention practice to enhance employee fit and reduce feelings of isolation. Furthermore, our analysis of control variables has revealed community fit to be significantly related to organisational status, suggesting mindfulness to affect the community fit of employees differently in public versus private sector organisations.

This study has also found mindfulness to have an optimistic association with the person-organisation fit and community fit individually. Additionally, there has been a positive indirect association found between mindfulness and person-organisation fit through community fit. However, isolation has been found to weaken the positive relationship between mindfulness and P-O fit by acting as a moderator.

We have also acknowledged that individual characteristics can influence the fit variables. While our primary focus has been on the relationship among mindfulness, isolation, community fit, and P-O fit, future research should explore how variables, such as gender, age, and job position, might independently affect these constructs, since previous research has shown similar correlations [72].

7.1. Theoretical Contributions

This study has enhanced the existing literature on both mindfulness and the P-O fit. Firstly, we have added to the theory of mindfulness by exploring how integrating it as a critical measure in HR practices can enhance employees’ overall fit. Then, taking constructs from mindfulness theory [16] and job embeddedness theory [17], we have formed and verified a model to ascertain theoretical associations among mindfulness, community fit, and person-organisation fit.

Our study has emphasized the importance of mindfulness interventions and mindfulness-based practices, such as Mindfulness Meditation (MM), Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR), Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT), Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and Integrative Body Psychotherapy (IBP), in fostering employees’ awareness within the organizational context. Studies have previously acknowledged that mindfulness can lead to positive individual outcomes in organisations, including job satisfaction [5] and higher work engagement [6], outstanding task performance [7], improved well-being [8], and also remarkable Organisational Citizenship Behaviour (OCB) [9]. Nevertheless, we are not aware of whether, when, and how mindfulness influences P-O fit, thus the discoveries in the current study have given rise to novel research avenues to review how mindfulness affects societal and organisational dynamics of individual employees and strengthens the interwoven connections among the humans, taking into account the mindfulness theory and job embeddedness theory.

Furthermore, we have extended the literature on community fit by demonstrating how individual factors may influence community fit among employees. Community fit, also known as fit-to-community, is increasingly recognized for its implications in job motivation, social networking behaviour, and organisational identification [23]. Our findings have suggested that HR departments utilizing mindfulness interventions can positively impact community fit, highlighting the organizational influence on community dynamics.

Lastly, by examining isolation as a moderator, we have displayed how an employee’s feeling toward self and others jointly relates to the person-organisation fit. We have found that isolation weakens the mindfulness association with P-O fit. The findings have indicated that the individual’s relation to the organisation is influenced by the interplay between HR-based mindfulness interventions and employees’ emotions of feeling isolated. Researchers in the HR domain agree that HR practices’ efficiency is associated with societal and organisational perspectives [73]. In conclusion, this study suggests that HRM interventions can yield diverse outcomes contingent upon employees' emotional states and relational dynamics within organizations. Future research directions include further exploring the role of mindfulness as a mitigator of isolation and advancing theories of loneliness management and work alienation in organizational settings.

7.2. Practical Implications

This study has articulated practical implications for HR practitioners. It has displayed that HR practitioners’ practice of mindfulness interventions (MBSR, MBCT, DBT, ACT) can build community fit and enhance person-organisation fit. Consequently, we may inspire organisations to include mindfulness practices as HRM interventions (talent retention, employee wellness, career development, organisation development, and so on), and impact their employees’ overall fit. To endorse mindfulness, we may inspire HR departments to employ mindfulness interventions [e.g., meditation, motivation for calmness, MBSR (Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction), MBCT (Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy), DBT (Dialectical Behaviour Therapy), ACT (Acceptance and Commitment Therapy), mindfulness workshops, and so on]. Moreover, HR departments could consider workplace spirituality and ethical or pro-social behaviour beyond core mindfulness practices, as suggested earlier [74]. Additionally, HR departments may endorse the spiritual quotient of employees by training them.

Furthermore, by employing isolation as a moderator, it has been proposed that the direct association amid the mediating model between mindfulness and P-O fit via community fit is more robust for employees with low isolation than high isolation. Therefore, in case of a lack of isolation among individual employees, HR practitioners should devote more energy or money to enhancing mindfulness among employees by employing interventions as the means to do so.

Alternatively, HR practitioners may pursue dealing with isolation in their organisations. For example, encouraging employees to cope with isolation; if an employee is practising mindfulness, but is feeling alone or isolated, P-O fit can even be reduced while mindfulness is present. Thus, it is also essential to deal with isolation so that the effect of mindfulness remains highly positive on P-O fit.

Lastly, we encourage organisations to focus on making employees fit with their community by providing them perquisites and allowances to keep them embedded in their communities. Various other work-life balance strategies, such as flexible hours, working from home, and encouraging social activities, can also help deliver positive outcomes for individuals as well as organisations in terms of person-organisation fit along with well-being, commitment, and work engagement.

7.3. Strengths and Limitations along with Future Directions

Indeed, this study has involved both strengths as well as limitations. The first limitation is that the study has gathered data using questionnaires in a cross-sectional study, which may sometimes lead to common method biases; nevertheless, the chances for biases were checked by using different tests, as suggested by Podsakoff [60]. Thus, our study, despite being of a cross-sectional design, has been free from any common method bias.

An additional vital point is our emphasis on interaction effects since an earlier study [75] presented that accrediting significant two-way interactions to common method biases can be very hard. Nevertheless, various checks of robustness have supported our foremost theories and findings. Also, in the present study, independent, mediating, and dependent variables have been assessed simultaneously and causal interpretations could not be made through the findings. However, future researchers can accumulate data about the principal variables in several instances.

Despite surging interest in mindfulness within different domains, organisational researchers pay only minute concentration to mindfulness and its organisational outcomes [76]. Also, our study has assumed that mindfulness leads to a P-O fit between employees and organisations, but it is sometimes difficult to achieve such an exact fit due to employees’ impressions, management tactics, and other biases [77]. Therefore, future research should measure the actual P-O fit or value similarity in understanding the role of employees in P-O fit in the organisation.

As discussed in the study about the emerging concept of social mindfulness [78], the idea could be explored in future research with only the perspective of social mindfulness.

CONCLUSION

Mindfulness has a direct as well as indirect association with person-organisation fit. Adopting mindfulness practices can enable community fit among employees and foster P-O fit, particularly when the employees feel isolated. The promotion of mindfulness interventions by HR among employees can pave the way to novel research possibilities that may assist in comprehending how employees find their fit concerning mindfulness interventions and feelings of isolation.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

M.Y.: Performed data analysis and interpretation of results; R.K. and R.Y.: Drafted the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| P-O fit | = Person-Organisation fit |

| HRM | = Human Resource Management |

| HR | = Human Resource |

ETHICAL STATEMENT

In accordance with the ethical guidelines of my institution and the STROBE guidelines, the study was deemed exempt from requiring formal ethical approval as it posed minimal risk to participants.