All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Role of Peer Relationships in Problematic Internet Use among Adolescents: A Scoping Review and Meta-analysis

Abstract

Background

The swift advancement of technology, particularly the internet, has significantly influenced various aspects of human life, resulting in both positive and negative consequences. In Indonesia, adolescents represent the largest group of internet users, with usage durations exceeding four hours per day, making them vulnerable to issues such as Problematic Internet Use (PIU). During adolescence, peer relationships play a crucial role in social development.

Objective

This study aims to explore how peer relations can influence problematic internet use among adolescents and identify strategic factors that contribute to reducing PIU based on systematic review findings. Additionally, the research seeks to quantify the relationship between peer relations and problematic internet use among adolescents through meta-analysis. The hypothesis posits a correlation between peer relations and problematic internet use among adolescents.

Results

Scoping review results indicate that, overall, peer relationships can have both positive and negative impacts on PIU. A more positive relationship between adolescents and their peers tends to correlate with lower levels of PIU. Conversely, adolescents with problematic peer relationships are more likely to develop PIU behaviours. Meta-analysis results further strengthen these findings, demonstrating a significant correlation between peer relationships and problematic internet use among adolescents (r = 0.191; p = 0.020; 95% CI).

Conclusion

Despite the significant correlation, the influence of peer relationships on problematic internet use appears to be relatively low. This suggests the existence of other factors that contribute to PIU behaviours beyond peer relationships.

1. INTRODUCTION

The rapid advancement of technology in the Industry 4.0 era has propelled society into a digital age where nearly every aspect of life is interconnected through the internet. The internet, a crucial technological innovation, has become an integral part of daily human life, facilitating communication across various domains [1]. Functioning as a network of interconnected computers, the Internet simplifies numerous aspects of life, including business, education, government, and other fields [2]. Presently, a significant portion of the global population is connected to the internet [3], with Indonesia ranking as the fourth-largest internet user in the world.

A survey conducted by the Indonesian Internet Service Providers Association (APJII) for the years 2021-2022 indicated that 77.02% of the Indonesian population was connected to the internet. This represents a significant increase, particularly during the pandemic, rising from 64.80% in 2018 to 77.02% in 2022. This growth is attributed to the shift towards online activities conducted from home during the pandemic, such as working from home and school from home. The devices used to access the internet included computers/laptops (0.73%), mobile phones/tablets (89.03%), and a combination of both (10.24%) [4]. Among the 77.02% of Indonesia's population using the internet, the distribution was as follows in Table 1 below:

| Province | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Java | 43.92% |

| Sumatra | 16.63% |

| Sulawesi | 5.53% |

| Kalimantan | 4.88% |

| Nusa Tenggara | 2.71% |

| Bali | 1.17% |

| Papua | 1.38% |

| Maluku | 0.81% |

| Internet Device | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Computer/laptops | 0.73% |

| Smartphone/tablets | 89.03% |

| Combination of both | 10.24% |

The highest increase in internet usage frequency in Indonesia occurs among teenagers (13-18 years old), reaching 76.63% with the duration of internet use as explained in Table 2.

| Time/day | Percentage | |

|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | |

| 1 – 5 hours | 49.59% | 53.74% |

| 6 – 10 hours | 33.11% | 30.75% |

| >10 hours | 14.16% | 11.26% |

Meanwhile, in the city of Surakarta, more than 73.5% of adolescents utilize the Internet for more than 4 hours daily [5].

The utilization of the internet brings about various benefits across different aspects of human life, such as facilitating communication, financial transactions, and the teaching-learning process. However, excessive internet use can lead to a range of physical and mental health disturbances, one of which is Problematic Internet Use (PIU) [6, 7]. PIU constitutes a multidimensional syndrome encompassing cognitive, emotional, and behavioural symptoms that result in difficulties for individuals in managing their lives offline [8, 9]. The duration of internet use is positively correlated with an increased vulnerability to PIU [10, 11], as well as addiction [6, 12, 13], Pornography addiction [14, 15], online gaming addiction [16, 17],

shopping and online gambling addiction [18, 19], nomophobia [20, 21], and various other disturbances [22]. For some individuals, the loss of a mobile phone or internet connection can generate significant stress [20].

Problematic Internet Use (PIU) was initially introduced by Davis in 2001 [23] as a distinctive pattern of internet-related cognition and behaviour with negative implications for one's life [24]. Davis delineated two forms of PIU: specific and general. General PIU encompasses multidimensional internet misuse, involving maladaptive cognition and behaviour not tied to specific content and negatively impacting both personal and professional aspects of life. On the other hand, specific PIU involves the excessive use or misuse of specific internet content functions, such as online gambling, stock trading, pornography, online gaming, and other specific content [25].

Several symptoms are identified in individuals suffering from Problematic Internet Use (PIU). These include a preference for online social interaction over face-to-face communication, mood regulation difficulties, cognitive preoccupation with the internet, and the emergence of negative behavioural outcomes [23, 26, 27]. The term PIU is often challenging to distinguish from Internet Addiction, yet both terms exhibit differences. Notably, PIU symptoms are considered non-clinical and non-pathological, while the symptoms associated with Internet Addiction, as articulated by Young and Abreu (2017), fall within the clinical and pathological domain [28].

While general Problematic Internet Use (PIU) may not fall within the realm of clinical and pathological symptoms, neglecting its impact can lead to various negative consequences. Some of the negative outcomes associated with general PIU include symptoms of depression [29, 30], sleep disturbances [31], feelings of loneliness [32, 33], narcissism [34, 35], aggression [36], and other psychosocial issues which can disrupt an individual's mental health [37, 38].

As per the data from APJII (2022) previously presented, adolescents constitute the highest internet users compared to other age groups in Indonesia. Consequently, Indonesia is one of the countries worldwide susceptible to symptoms of Problematic Internet use (PIU), particularly among adolescents. Adolescence marks the transitional phase from childhood to adulthood, typically spanning from ages 12 or 13 to the early twenties [39]. During this period, the social environment of adolescents expands significantly compared to their childhood [40]. Adolescents face numerous challenges during this phase, both from within themselves and their surroundings. Failure to cope with these challenges may lead to complex health issues encompassing both physical and mental aspects [41]. Recognizing adolescents' vulnerability to PIU is crucial for developing effective interventions to support their overall well-being during this critical developmental stage.

During adolescence, individuals commonly develop closer relationships with peers compared to their parents [42]. In this period, peers play a crucial role as a significant source of social influence in an individual's life [43]. Moreover, the influence of peers tends to be more dominant than that of parents during adolescence [44].

Peer relationships constitute interpersonal connections established and cultivated among individuals of the same age group or those with similar levels of psychological development during social interactions [45]. Some children and adolescents possess the ability to form positive friendships, earning the favour of their peers, while others may face rejection from their peer groups [46]. The acceptance or rejection experienced by peers can significantly impact the behaviour and development of adolescents. Understanding the dynamics of peer relationships during this developmental stage is essential for comprehending their influence on adolescent behaviour and overall growth.

Adolescents who their peers accept tend to exhibit positive behaviours, such as academic achievement and prosocial conduct [47]. Conversely, adolescents experiencing peer rejection are more prone to negative risk factors such as aggression and depressive symptoms [48, 49]. Nevertheless, not all adolescents are easily influenced by peer acceptance or rejection due to individual differences in susceptibility to peer influence [46]. For instance, some children and adolescents may be more vulnerable to the negative impacts of peer victimization [50, 51] or may experience more positive outcomes when accepted by their peers [52]. Therefore, it is crucial to understand individual differences in vulnerability to peer acceptance and rejection among adolescents.

In the current internet era, adolescents learn, imitate, and develop internet usage behaviours from various sources, including interactions with their peers [53]. This is supported

By several studies indicating that peer relations influence problematic internet use among adolescents [29, 54]. However, there are also studies suggesting that peer relationships do not have a significant impact on the emergence of PIU in adolescents [55]. The contrasting findings highlight the complexity of the relationship between peer influence and PIU, emphasizing the need for further research to understand the nuanced dynamics of these interactions in the context of the internet.

This research aims to explore the impact of peer relations on problematic internet use (PIU) among adolescents. Additionally, the study seeks to identify strategic factors contributing to the reduction of PIU based on the findings from a systematic review. The research further endeavours to quantify the relationship between peer relations and problematic internet use among adolescents through a meta-analysis.

The formulated hypotheses for this study posit a significant relationship between peer relations and problematic internet use among adolescents. Through systematic review and meta-analysis methodologies, the research aims to provide insights into the nuanced dynamics of peer influence on PIU, uncover strategic factors mitigating PIU, and quantitatively assess the strength of the association between peer relations and problematic internet use among adolescents. The findings of this study are expected to contribute to a deeper understanding of the complex interplay between peer relations and PIU, offering valuable implications for interventions and preventative measures targeting adolescent internet usage behaviours.

2. METHODS

This research employs the Systematic Literature Review (SLR) and meta-analysis methodologies. SLR involves collecting, selecting, extracting, and evaluating relevant scholarly articles on the topic [56]. The specific type of SLR used in this study is a scoping review, which is a systematic and qualitative literature synthesis method [57]. Article retrieval was conducted using Scopus, a comprehensive literature database that provides abstracts or summaries of formally reviewed scientific literature [58].

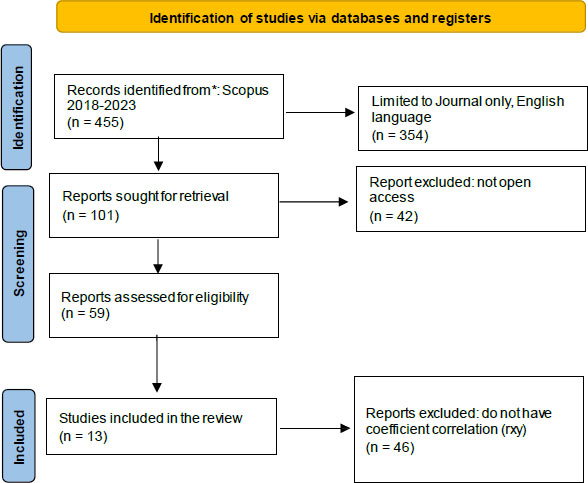

The steps of a scoping review include: 1) Identifying the research question; 2) Identifying relevant studies; 3) Selecting studies to be included in the review; 4) Charting the data; 5) Collating, summarizing, and reporting the results; 6) Consulting stakeholders (optional) [57]. The research question in this study is: “How does peer relationship contribute to problematic internet use in adolescents?” A literature search was conducted using the Scopus database with the keywords “problematic internet use” and “peer” from November 10 to November 20, 2023. Literature selection followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. Article selection was based on eligibility criteria, including inclusion and exclusion criteria. Inclusion criteria encompassed: 1) Scientific articles written in English, 2) Literature in the form of scientific articles published in Scopus-indexed journals, 3) Articles published from 2018 to 2023, and 4) Journals being open access. Exclusion criteria included 1) Scientific articles without full-text access and 2) Literature reviews or qualitative research articles. Articles that did not meet the criteria were excluded and not used in this study. The next step involved data extraction for analysis in the form of a synthesis matrix table.

This research adopts the SPIDER framework (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research Type) to delimit its scope effectively. The components of the SPIDER framework for this study are as follows in Table 3:

| Component | Information |

|---|---|

| Sample | Adolescents |

| Phenomenon of Interest | Problematic Internet Use |

| Design | Correlation |

| Evaluation | The role of peer relationships on problematic internet use in adolescents |

| Research type | Quantitative |

Utilizing a quantitative correlational design, this study aims to explore the correlation between peer relationships and problematic internet use among adolescents. The research focuses on understanding how peer relationships contribute to or mitigate problematic internet use in the adolescent population. The SPIDER framework provides a structured approach to guide the research methodology and ensures clarity in defining the sample, phenomenon of interest, design, evaluation, and overall research type. The findings from this study are expected to contribute valuable insights to the existing literature on the complex relationship between peer interactions and problematic internet use among adolescents.

After completing the scoping review phase, the next step is meta-analysis, a statistical method for combining results from different studies, especially those with small sample sizes or conflicting outcomes. Data analysis for the meta-analysis was conducted using JASP 0.18.1.0 software.

3. RESULT

3.1. Scoping Review

The initial data search was conducted from November 10 to November 20, 2023, resulting in the identification of 954 journals indexed in Scopus. The selection process involved both inclusion and exclusion criteria. In the first stage, the researcher restricted the publication years to those between 2018 and 2023, excluding journals published outside this timeframe. After this exclusion based on publication years, the result was 455 journals. Subsequently, these journals were further excluded based on the following criteria: 1) Scientific articles written in English, 2) Literature in the form of scientific articles published in Scopus-indexed journals, 3) Articles published from 2018 to 2023, and 4) Journals being open access. Following this exclusion process, 101 journals were included. Another round of exclusion was performed by adding the keyword “adolescence,” resulting in 59 journals. Lastly, the researcher included open-access journals with correlation coefficient (r) values, enabling meta-analysis. This led to the selection of 13 journals, as illustrated in the PRISMA diagram below in Fig. (1):

The selected article is subsequently extracted and analysed as follows in Table 4:

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

| No | Title | Author | Country | N | Subject |

M Age |

Peer Relation Test | PIU Test | Variable | r | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cyberbullying and PIU among adolescents before and during COVID- 19 pandemic: The association with adolescents relationships |

[55] (Eden et al., 2023) |

Israel | 348 | 13 - 18 years old |

15.05 | NRI RQV | SMUQ (Social Media Use Question naire) |

Peer Relations | -0,267 | The research results indicate that peer relationships are negatively correlated with cyberbullying and Problematic Internet Use (PIU). This implies that adolescents with the ability to establish positive peer relationships tend to exhibit lower levels of cyberbullying and PIU |

| 2 | Problematic internet use as a moderator between personality dimensions and internalizing and externalizing symptoms in adolescence |

[59] (Fontana et al., 2023) |

Italia | 231 | 15 - 19 years old |

17.1 | APS-Q (Adolescent Personality Structure Questionnaire) YSR (Youth Self Report) |

IAT (Internet Addictio n Test) |

Peer Relations | -0,05 | Adolescents with the ability to establish positive relationships with peers tend to have lower levels of Problematic Internet Use (PIU). |

| 3 | Quality of life and mental health of adolescents: Relationships with social media addiction, fear of missing out, and stress associated with neglect and negative reactions by online peers | [60] (Dam et al., 2023) |

Vietnam | 1891 | 17 - 25 years old |

17 | FOMO questionnaire |

PIUQ SF 6 | Peer Problems | 0,29 | Problematic Internet Use (PIU) in adolescents can lead to various disorders, one of which is social media addiction. The results of this study indicate that social media addiction is associated with Fear of Missing Out (FOMO), peer rejection, and neglect. This overall has an impact on increased depression and quality of life |

| 4 | Psycho-social correlates of cyberbullying among polish adolescents | [61] (Rębisz et al., 2023) |

Poland | 541 | 14-15 years old |

NA | 1. The peer support scale is derived from the educational relationship functioning questionnaire 2. The disrupted peer role questionnaire |

PIU Scale |

1. Peer support & PIU 2. Threats from peers & PIU 3. Peer rejection & PIU 4. Dislike of peers & PIU |

-0,27 0,38 0,25 0,27 |

Problematic Internet Use (PIU) in adolescents has an impact on the occurrence of cyberbullying. This study concludes that personal variables such as emotional self- regulation, social skills, and peer relationships significantly influence cyberbullying behavior. |

| 5 | Multigroup analysis of the relationship between loneliness, fear of missing out, problematic internet usage, and peer perception in gifted and normally | [62] (Tatlı & Ergin, 2023) |

Turkey | 661 | 11-18 years old |

NA | Generalized Peer Relationship Scale | Dysfunct ional Internet Usage Scale (NIUS) | Peer relationship & PIU | -0,18 | Problematic internet use is negatively associated with peer perceptions. Additionally, it is also interrelated with face-to-face communication issues and interpersonal relationships. |

| 6 | Developing adolescents generalized and specific problematic internet use in central siberia adolescents: A school-based study of prevalence, age–sex depending on content structure, and comorbidity with psychosocial problem |

[63] (Tereshchenko et al., 2022) |

Rusia | 4514 | 12 - 18 years old |

14.52 | Chen Internet Addiction Scale (CIAS) | Strength s & Difficulti es Question naire (SDQ) |

Peer Problems & PIU | -0,81 | This study found that problematic internet use (PIU) among adolescents in Central Siberia is quite high, with a prevalence of 7.2% for general PIU, 10.4% for gaming PIU, and 8.0% for social media PIU. There is a significant relationship between PIU and psychosocial problems, especially with peer relationships. |

| 7 | The effects of school climate, parent- child–child closeness, and peer relations on the problematic internet use of Chinese adolescents: Testing the mediating role of self-esteem and depression |

[53] (Wang, 2022) |

China | 960 | 15 - 18 years old |

14.86 | The peer relationship scale | Problematic social media use | Peer Relations & PIU | -0,187 | The research findings indicate that school climate, parent-child closeness, and peer relationships have a direct effect on problematic internet use (PIU) among Chinese adolescents. Peer relationships are negatively correlated with PIU. The effects of these factors are also mediated by self-esteem and depression. |

| 8 | School-based relationships and problematic internet use among Chinese students | [64] (Hayixibayi et al., 2021) |

China | 6552 | 10 - 19 years old |

13.51 | Conflict with peers, teacher & other school staff questionnaire | Adolescent Pathological Internet Use Scale (APIUS) | Conflict with peer & PIU | 0,211 | The higher the conflict between adolescents and peers and the conflict with teachers, the higher the scores for Problematic Internet Use (PIU) in adolescents. Adolescents who are connected with school and have a positive classroom atmosphere are associated with lower PIU scores. |

| 9 | Online activities as risk factors for Problematic internet use among students in Bahir Dar University, North West Ethiopia: A hierarchical regression model | [65] (Asrese & Muche, 2020) |

Ethiopia | 812 | Adolescents | NA | Peer Pressure Scale | IAT | Peer Pressure & PIU | 0,152 | There is a significant positive relationship between peer pressure and the risk of Problematic Internet Use (PIU). Peer pressure on adolescents increases the risk of PIU |

| 10 | Peer victimization and adolescent internet addiction: The mediating role of psychological security and the moderating role of teacher-student relationships | [66] (Jia et al., 2018) | China | 747 | Adolescents | 13.73 | Adolescent peer victimization questionnaire inventory of parent and peer attachment |

Young’s IAT | Peer Victimizati on & PIU PIU & Teacher Student Relationshi p |

0,14 -0,33 |

Peer victimization is positively correlated with problematic internet use and negatively correlated with the teacher-student relationship. This means that adolescents who have positive relationships with teachers tend to have lower levels of peer victimization and problematic internet use. |

| 11 | Online addictions among adolescents and young adults in Iran: The role of attachment styles and gender | [67] (Salehi et al., 2023) |

Iran | 372 | 17 - 19 years old |

NA | The Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ) | PIUQ-9 | Secure peer attachment & PIU insecure peer attachment & PIU |

-0,45 0,31 |

Internet addiction is negatively correlated with a secure attachment style in adolescent peer relationships and positively correlated with an insecure attachment style. |

| 12 | The influence of parents and peers on adolescents’ problematic social media use revealed | [47] Leijse et al, 2023 |

China | 2758 | 10 – 19 years old |

13.53 | Peer support of the multidimension al scale of perceived social support peer pressure scale |

SMD- scale |

Peer support peer pressure scale |

-0,43 0,278 |

Adolescents who have support from peers tend to develop lower levels of Problematic Internet Use (PIU) compared to adolescents who experience pressure from their peers. |

| 13 | Association between problematic internet use and behavioral/emotional problems among Chinese adolescents: the mediating role of sleep disorders |

[43] (Wang et al., 2021) |

China | 1976 | 11-18 years old |

13.6 | Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) | Young’s IAT | Peer problem | 0,12 | The research results indicate that peer problems are positively correlated with Problematic Internet Use (PIU). This means that adolescents who experience difficulties in their relationships with peers tend to develop higher levels of PIU. |

This article review shares common characteristics, being published between 2018 and 2023 and being indexed in Scopus. The articles originate from both developed and developing countries, with five articles from China and one article each from Israel, Italy, Vietnam, Poland, Turkey, Russia, Ethiopia, and Iran. The research methodology employed in these articles is quantitative.

Based on the review of 13 articles, two main themes emerged from the scoping review regarding peer relations and peer problems. The findings can be seen in the Table 5 below:

Peer relationships refer to interactions and reciprocal relationships between individuals who share similar age, status, or social standing [47]. These relationships can develop in various contexts, such as among classmates, colleagues, or social groups. Healthy peer relationships often involve communication, mutual respect, and cooperation, fostering positive peer support and peer attachment [67]. Research findings indicate that positive peer relationships are negatively correlated with problematic internet use (PIU). Adolescents who are able to form positive peer relationships tend to exhibit lower levels of PIU [68]. Forms of positive peer relationships can include peer support [47, 69] and peer attachment [67, 70, 71].

In addition to peer relationships, findings from a scoping review also indicate that peer problems influence the condition of problematic internet use (PIU) among adolescents. Research shows that adolescents who experience difficulties in peer relationships are at higher risk of developing PIU [60, 63]. Common issues that arise in peer relationships include threats from peers [61], peer rejection [52, 72], dislike of peers [52, 61], conflicts with peers [65], and peer pressure [47, 73].

3.2. Meta-analysis

After conducting a scoping review, to ascertain the correlation between peer relationships and problematic internet use, the researcher conducted a meta-analysis study.

Based on the findings from 13 articles identified in the scoping review, a meta-analysis process was undertaken as follows in Table 6 below:

Table 6.

| No. | N | Age | rxy | z | Vz | SEz | Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 348 | 13 - 18 | -0,267 | 0,274 | 0,003 | 0,054 | PIU & Peer problem |

| 2 | 231 | 15 - 19 | 0,61 | 0,709 | 0,004 | 0,066 | PIU & Peer problem |

| 3 | 1891 | 17 - 25 | 0,29 | 0,299 | 0,001 | 0,023 | PIU & Peer problem |

| 4 | 943 | 17 - 25 | 0,29 | 0,299 | 0,001 | 0,033 | PIU & Peer problem |

| 5 | 541 | 14 - 16 | -0,27 | -0,277 | 0,002 | 0,043 | PIU (Cyber victim) & peer support |

| 6 | 541 | 14 - 16 | 0,38 | 0,400 | 0,002 | 0,043 | PIU (Cyber victim) & threats from peers |

| 7 | 541 | 14 - 16 | 0,25 | 0,255 | 0,002 | 0,043 | PIU (Cyber victim) & peer rejection |

| 8 | 541 | 14 - 16 | 0,27 | 0,277 | 0,002 | 0,043 | PIU (Cyber victim) & dislike of peers |

| 9 | 661 | 12 - 18 | -0,18 | -0,182 | 0,002 | 0,039 | PIU & Peer Relations |

| 10 | 4514 | 12 - 18 | 0,81 | 1,139 | 0,000 | 0,015 | PIU & Peer problem |

| 11 | 1006 | 15 - 19 | -0,19 | -0,189 | 0,001 | 0,032 | PIU & Peer Relations |

| 12 | 494 | 15 - 19 | -0,25 | -0,251 | 0,002 | 0,045 | PIU & Peer Relations |

| 13 | 312 | 14 - 21 | -0,14 | -0,142 | 0,003 | 0,057 | PIU & Peer Relations |

| 14 | 7868 | 13 - 18 | 0,2 | 0,203 | 0,000 | 0,011 | PIU & Peer Problem |

| 15 | 747 | Adolescence (NA) | 0,14 | 0,141 | 0,001 | 0,037 | Peer victimization & PIU |

| 16 | 6552 | Adolescence (NA) | 0,211 | 0,214 | 0,000 | 0,012 | PIU & Conflict with peer |

| 17 | 1976 | Adolescence (NA) | 0,12 | 0,121 | 0,001 | 0,023 | PIU & Peer Problem |

| 18 | 812 | Adolescence (NA) | 0,152 | 0,153 | 0,001 | 0,035 | Peer pressure |

| 19 | 1384 | 11 - 19 | -0,43 | -0,460 | 0,001 | 0,027 | PIU & Peer Relations |

| 20 | 1384 | 11 - 19 | 0,278 | 0,286 | 0,001 | 0,027 | PIU & Peer Problem |

The outcomes of this coding were further analyzed using JASP version 0.18.1.0, producing the following results that the analyzed articles are heterogeneous (Q = 4172.411; p < 0.001). Therefore, a Random Effects model is more suitable for estimating the mean effect size of the analyzed articles. The results of the analysis also suggest the potential for developing moderator variables that may influence the relationship between peer relations and problematic internet use in adolescents.

Based on the results of the above meta-analysis in Table 7, peer relationships correlate significantly with problematic internet use in adolescents (r = 0.190; p = 0.020; 95% CI). Although there is a significant correlation, peer relationships have a relatively low influence on problematic internet use behavior.

| Coefficients | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | Estimate | Standard Error | z | p |

| Intercept | 0.191 | 0.082 | 2.326 | 0.020 |

| Coefficients | ||||

| Estimate | Standard Error | z | p | |

| Note. Wald test. | - | - | - | |

The forest plot, with a 95% confidence interval and data from 13 studies, indicates that the effect size of the research ranges from Zr = 0.03 to Zr = 0.35. The Cochran's Q test result is 4172.411 with p < 0.001, leading to the rejection of the homogeneity hypothesis. Meanwhile, the I2 value reaches 99.466%, which is considered high according to the criteria of Higgins and Thompson [74]. Based on the results of the Egger’s test (z = -0.736; p = 0.462) and Kendall’s test (τ = 0.120; p = 0.492), which indicate publication bias.

4. DISCUSSION

The increasing use of the internet has both positive and negative impacts [75]. Adolescents, being the highest internet users in Indonesia [4], constitute a vulnerable group susceptible to these effects, one of which is problematic internet use (PIU) [48]. PIU encompasses excessive use of the internet, involving all forms of internet applications that lead to problematic and maladaptive behaviors in general [76, 77]. Several studies indicate that PIU has various negative effects on adolescents, such as depressive symptoms [1, 78], sleep disturbances [79], academic issues [80], interpersonal disruptions [81, 82], loneliness [83], and various other mental health disorders [84-86].

Considering that adolescents are a more vulnerable age group to the detrimental effects of PIU compared to other age groups [87], it is essential to conduct further research on PIU in adolescents. Some children and adolescents have the ability to establish positive friendships, making them liked by their peers [44, 88], while others may not be favored by their peer groups [47]. The various acceptances and rejections from peers can influence the behavior and development of adolescents [89].

Adolescence is one of the developmental stages occurring between the ages of 10 and 18 years, representing a transition from the childhood phase to adulthood [38, 90]. This period is characterized as a critical developmental phase marked by significant changes in biological, social, and cognitive domains. It is commonly divided into three stages: early adolescence (10- 12 years), mid-adolescence (13-15 years), and late adolescence (16–18 years) [91].

Generally, adolescents tend to develop closer relationships with their peers compared to their parents [42]. During this period, peers become a crucial source of social influence in an individual's life [44]. The relationship between adolescents and their peers is a highly significant and mutually influential interaction during this phase [53]. In the current internet era, adolescents also learn, imitate, and develop their internet behaviors through interactions with their peers [53].

Adolescents who possess the ability to establish positive friendships are more likely to be liked and accepted by their peer groups [92], while others may not be favored by their peers [72]. Various forms of acceptance or rejection from peers can influence the behavior and development of adolescents [72, 93].

Based on the stated research questions, the discussion will be classified into two sections. For the first research question, “How can peer relationships influence problematic internet use among adolescents? And what strategic factors play a role in reducing PIU based on the results of a systematic review?” will be addressed through a scoping review. Subsequently, a meta-analysis will be conducted to examine the extent to which peer relationships can influence problematic internet use among adolescents.

4.1. Scoping Review

The scoping review of 13 research articles indexed in Scopus revealed two themes related to the correlation between peer relationships and PIU: peer relations and peer problems. The peer relations theme is further divided into two sub-themes: peer support and peer attachment. Meanwhile, peer problems are subdivided into several sub-themes, namely threats from peers, peer rejection, dislike of peers, conflict with peers, and peer pressure.

Supportive peer relationships (peer support) contribute to individual protection and play a role in optimizing the complex socio-emotional development, cognitive skills, and learning of adolescents [47, 94]. Positive peer support enhances the psychosocial abilities of adolescents [63], promotes resilience in adolescents, and reduces negative behaviors in this age group [45]. Furthermore, positive peer relationships have been found to correlate negatively with problematic internet use [53]. In other words, adolescents with positive relationships with their peers tend to have lower levels of problematic internet use.

Adolescents who their peers accept tend to develop positive behaviors such as academic achievement and prosocial behavior [52]. However, adolescents who face challenges in forming friendships with peers may pose negative risk factors such as aggression and depressive symptoms [61]. Various issues in peer relationships may include threats from peers, rejection, and dislike by peers [72]. Additionally, conflicts with peers [54], peer pressure [47, 73], peer victimization [47, 73] and cyberbullying [95] can occur among adolescents. Adolescents facing challenges in peer relationships are likely to experience higher levels of problematic internet use compared to those with positive peer relationships [52].

Unsatisfactory peer relationships can act as stressors and, in the long term, may lead to negative academic behavior and psychological consequences [52]. Additionally, peer support can prevent the occurrence of problematic social media use [47].

Several studies also revealed that adolescent attachment, whether with parents or peers, correlates with PIU [71, 96, 97]. Adolescents undergo a transition in attachment from parents to peers [72, 98]. Adolescents with secure attachment to their parents will build trust and stable relationships with their peers [96, 98]. Some studies also indicated a relationship between internet use and the quality of peer relationships. Excessive internet use is negatively associated with the quality of peer relationships. Additionally, school-related stress and poor relationships with teachers, students, and parents are factors contributing to excessive internet use [53, 99, 100].

Problematic internet use is negatively correlated with secure attachment, whether with parents or peers (r = -0.45) and positively correlated with insecure attachment (r = 0.31) [67]. Adolescents with insecure peer attachment tend to have low social skills, making them lonely in the real world and preferring to engage in social interactions online [98]. Therefore, insecure peer attachment is one of the factors contributing to problematic internet use. On the other hand, adolescents with secure peer attachment are more likely to form friendships in the real world, providing them with better protection against PIU [101].

In other words, adolescents who can establish peer relationships characterized by secure attachment are likely to have lower problematic internet use compared to adolescents with insecure peer attachment [98]. Therefore, to prevent problematic internet use in adolescents, efforts are needed to develop adolescents' abilities to build positive peer relationships in the real world.

Based on the two themes found in the review process, it can be concluded that, in general, peer relationships have both positive and negative impacts on PIU. The more positive the relationship between adolescents and their peers is, the lower the tendency for PIU. Conversely, adolescents with problematic peer relationships tend to develop PIU behaviors.

4.2. Meta-analysis

Based on the results of the meta-analysis conducted by the researcher, it was found that peer relationships correlate significantly with problematic internet use in adolescents (r = 0.190; p = 0.020; 95% CI). Although it correlates significantly, the peer relationship has a relatively low impact on problematic internet use behavior. This implies that there are other factors influencing PIU behavior besides peer relationships.

Several previous studies have revealed that, in addition to peer relationships, the school environment and parent-child closeness can also influence the occurrence of PIU in adolescents [53, 102]. A negative school climate, lack of supervision, and discipline can lead students to become uncontrollable. Students may struggle to control themselves, including when using the internet [103]. Conversely, a positive and authoritative school climate implementing discipline is likely to shape focused and disciplined students [64].

In addition to the school climate, the closeness between parents and adolescents can also influence the prevention of PIU [104]. A satisfying parent-child relationship fosters a sense of security and mutual ownership in adolescents [102]. This tendency is likely to reduce deviant behavior in adolescents, including internet usage behaviors [105]. In the realm of social interaction, adolescents can emulate and influence each other, especially regarding internet usage, through peer relationships. High-quality peer relationships have the potential to diminish the inclination toward PIU in adolescents [53].

In addition to demonstrating the association between peer relationships and problematic internet use in adolescents, the results of the meta-analysis also indicate the presence of biases in the research. Publication bias can occur due to various reasons, including 1) errors in determining the sample size and selection methods; 2) inaccuracies in measuring independent and dependent variables; 3) errors in dichotomizing variables; 4) variations in the range of dependent and independent variables; 5) deviations in construct validity for both dependent and independent variables; 6) mistakes in data collection, data processing, and data interpretation; 7) other factors that may influence the occurrence of bias in the study [106].

CONCLUSION

The results of the scoping review and meta-analysis regarding the role of peer relationships in problematic internet use consistently show that there is a correlation between peer relationships and problematic internet use in adolescents. This means that the research hypothesis that there is a correlation between peer relationships and problematic internet use in adolescents is accepted. The more positive the relationship between adolescents and their peers, the tendency

for problematic internet use to be lower. Conversely, adolescents with problematic peer relationships tend to develop problematic internet use behaviors. However, based on the meta- analysis results, the correlation between peer relationships and problematic internet use tends to be low (r = 0.190; p = 0.020; 95% CI). In other words, there are other factors influencing problematic internet use behavior besides peer relationships that need to be further explored in future research. These other factors include family functioning, adolescent-parent relationships, relationships with school and teachers, and other potential influencing factors.

LIMITATION AND FUTURE RESEARCH

The current research is literature-based, focusing on examining a single correlation, namely, the relationship between peer relationships and problematic internet use in adolescents. This opens up opportunities for further research on problematic internet use (PIU) in adolescents and the influencing factors. Additionally, the possibility of biases in previous studies strengthens the argument for the need for further investigation into PIU. Through such additional research, it is anticipated that new knowledge and solutions can emerge to prevent and address PIU in adolescents. Besides, this literature review is limited to open-access literature indexed by Scopus. Therefore, there is still an opportunity for future literature reviews to utilize a broader range of sources beyond Scopus.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

It is hereby acknowledged that all authors have accepted responsibility for the manuscript's content and consented to its submission. They have meticulously reviewed all results and unanimously approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| PIU | = Problematic Internet Use |

| SLR | = Systematic Literature Review |

| PRISMA | = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| SPIDER framework | = Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, and Research Type |

| SDQ | = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

FUNDING

The research team would like to express our gratitude to the Ministry of Education and Culture of Indonesia. This research was conducted in collaboration with the Faculty of Psychology at Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Indonesia and was funded by the Indonesian government through the Doctoral Dissertation Research Grant (PDD-DRTPM) from the Ministry of Education and Culture of Indonesia in 2024, under contract number 108/E5/ PG.O2.00.PL/2024.