All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Self-esteem, Self-objectification, Appearance Anxiety, Resilience, and Gender: Testing a Moderated Mediational Analysis

Abstract

Background

Appearance anxiety has been associated with difficulties in establishing social relationships and an increased vulnerability to various psychological illnesses such as eating disorders, depression, and social anxiety. However, only a few studies have examined influencing factors of appearance anxiety, especially risk and protective factors associated with appearance anxiety is still lacking.

Objective

This study investigated the mediating role of self-objectification in the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety and the moderating role of resilience and gender.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 437 university students (203 females and 234 males) aged 18–24 years (Mage = 21.89, SD = 1.59). The data was collected using questionnaires and analyzed through bivariate correlations, mediational analysis, and moderated mediational analysis.

Results

Results revealed that higher self-esteem negatively predicted self-objectification and appearance anxiety, while self-objectification significantly mediated the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety. Moderated analysis revealed that resilience was a significant moderator, and the direct effect of self-esteem on appearance anxiety was moderated in both men and women. Moreover, the moderated mediational analysis also suggested that higher than mean levels of resilience significantly moderated the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety via self-objectification.

Conclusion

The study has practical and theoretical contributions to resilience, self-objectification, and appearance anxiety. It concluded that the negative effects of appearance anxiety and self-objectification on mental health may be reduced by increasing self-esteem and resilience.

1. INTRODUCTION

Higher engagement in upward social comparison on social media platforms increases concern about the physical appearance among adolscents and young adults, leading to appearance-related anxiety [1-3]. Appearance anxiety refers to a fear of being negatively evaluated for physical appearance, including body and face shape, body color, height, and weight [4]. Prior studies have reported that active social media users, particularly young adults, often receive feedback from peers, family members, and relatives about their appearance [5]. Additionally, they are more likely to seek others’ attention and engage in social comparisons regarding their appearance, which increases their risk of appearance anxiety [5]. It has been linked to difficulties in forming social relationships [6], further increasing vulnerability to psychological issues such as eating disorders and depression [7]. Moreover, appearance anxiety is positively associated with social anxiety [4] and body dissatisfaction [8] and negatively associated with self-esteem [9], life satisfaction [10], and well-being [11]. Meanwhile, previous research revealed that appearance anxiety is associated with a greater likelihood of dating-related anxiety and social anxiety in young people [12, 13].

In India, societal pressure regarding physical appearance and grooming significantly impacts various aspects of life, including success, marriage prospects for girls, and employment opportunities [14]. Indian adolscents and young adults place significant importance on appearance, often spending a substantial portion of their income on grooming and maintaining their physical image to gain social approval [15, 16]. They heavily depend on the cosmetics industry and beauty products to enhance their appearance [14]. However, only a few studies have examined influencing factors of appearance anxiety, especially risk and protective factors associated with appearance anxiety is still lacking. Therefore, identifying potential protective factors for reducing appearance anxiety and promoting overall wellness among adolescents and young adults is urgently needed.

1.1. Self-esteem and Appearance Anxiety

Self-esteem refers to how we value and perceive ourselves, shaped by personal beliefs that are typically resistant to change. It is considered a basic determinant of human behavior [17]. Our self-esteem influences whether we love and value ourselves as individuals or not. It may also affect how effectively or reactively we respond to and manage the situations. Self-esteem can be defined as a combination of thoughts, feelings, emotions, and experiences that shape and influence social connections [17]. Low self-esteem plays an important role in the development of appearance anxiety [18]. People with low self-esteem frequently hold negative beliefs about their self-worth and physical appearance, and they believe that they are worthless and useless. Low self-esteem is recognized as a risk factor for the onset of social anxiety symptoms, with negative self-evaluations significantly contributing to the development and persistence of appearance anxiety [19]. Individuals with low self-esteem may perceive themselves as less valuable in the eyes of others, making it challenging for them to initiate social relations [19]. A study conducted on adolescent participants reported that lower self-esteem in adolescents predicted higher levels of avoidance motivation, social anxiety, and appearance anxiety [18]. Conversely, a study utilizing structural equation modeling revealed that higher self-esteem among volunteer women was negatively associated with appearance anxiety [20]. Moreover, a cross-sectional study conducted among 219 university students suggested that higher self-esteem was negatively related to social physique anxiety [9]. Past studies have supported the current objective that lower self-esteem is positively associated with appearance anxiety. Hence, in the present study, self-esteem will be considered a significant predictor of appearance anxiety.

1.2. Self-objectification as a Mediator

A considerable body of research has shown that women are targeted for sexually objectifying their bodies in their day-to-day lives more often than men [21, 22]. In India, women have undoubtedly been experiencing objectification for thousands of years [23]. Ancient Indian scriptures and architectural representations contain numerous examples of the sexual objectification of women. In contemporary times, self-objectification among females is evident through the growing use of software like Photoshop, the expansion of the makeup industry, the popularity of plastic and cosmetic surgery, and other related trends [24]. This is a common issue affecting females around the world and has a significant negative effect on the identities of women [23, 25]. Although the objectification theory was initially developed with a focus on sexual objectification or physical objectification of females' experiences, recent research has also explored its relevance in investigating men’s experiences. Empirical studies revealed that men generally receive feedback that their height, weight, muscle, and strength are more important than their actual potential and abilities [22, 26]. Previous studies have also revealed that self-objectification is associated with several negative consequences and various adverse mental health issues, especially eating disorders, appearance anxiety, body shaming, depressive mood, sexual dysfunction [27, 28], and other physical health issues [29].

Self-objectification refers to a process where an individual perceives themselves as an object to be used and evaluated rather than a human being [21, 30]. A cross-lagged study on undergraduate women reported that self-objectification significantly mediated the relationship between contigent self-worth and self-esteem correlation between self-objectification and appearance-dependent self-worth, leading to higher levels of appearance anxiety and, ultimately, lower self-esteem. On the other hand, higher self-objectification is negatively correlated with self-esteem and positively correlated with appearance anxiety, depression, and other psychological and mental health issues [18, 19]. Another study reported that self-objectification of Chinese undergraduate students positively mediated the relationship between celebrity worship behavior and consideration of cosmetic surgery [31]. Moreover, in the case of Australian female students, a longitudinal study acknowledged that the experience of sexual harassment significantly increased self-objectification within one year of follow-up [32]. Subsequently, the mediating effect of self-objectification increased the risk of higher weight and shape concerns after one year of the follow-up period. Self-objectification was considered to be a significant mediator of the connection between sexual harassment and eating disorders, as well as psychological distress and body shame [33]. However, there is a scarcity of empirical studies examining the mediating role of self-objectification in the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety.

1.3. Resilience as a Moderator

Resilience refers to a person's bounce back ability to successfully handle or overcome adversity, manage stress, and rise above challenges [34]. Some studies have investigated the moderating role of resilience in relation to the perception of psychological health [35], perception of workload [36], affected disorder, and health-related quality of life in adolescents and young adults with multiple sclerosis [37]. Previous studies also suggested that resilience significantly moderated the relationship between stressful life and postpartum depression among women [38]. Moreover, resilience is strongly associated with one’s mental health and well-being. It protects us from adverse psychological events, including social, cultural, and family contexts [39]. However, research on the moderating role of resilience in the relationships between self-esteem and appearance anxiety, as well as self-esteem and self-objectification, remains limited.

1.4. Gender as a Moderator

A cross-lagged study in China suggested that females often experience poorer self-esteem compared to boys, partly due to the social valuation of stereotypical female roles and higher cultural emphasis on women’s physical attractiveness [40]. Research with secondary school students demonstrated that self-esteem was negatively associated with appearance anxiety in both genders [41]. Additionally, a correlational study found that females have greater degrees of appearance anxiety than their counterparts [2].

Moreover, previous studies have revealed that usage of social media platforms drives the internalization of body ideals, which significantly leads to a greater focus on physical beauty and appearance, especially for women [42]. Feedbacks related to physical appearance greatly influence women’s identity, self-esteem, and life satisfaction, further leading to appearance-related issues such as anxiety and body shaming [30]. While self-objectification and appearance anxiety have typically been examined in female participants, some recent studies revealed that men are also affected by these societal pressures [6, 22]. However, evidence regarding gender differences in self-esteem, self-objectification, and appearance anxiety has reported mixed findings. Additionally, we found limited empirical studies on the moderating role of gender in the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety. Hence, this study gives a modest attempt to evaluate the moderating roles of gender in the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety, as well as between self-objectification and appearance anxiety.

1.5. The Rationale of the Current Study

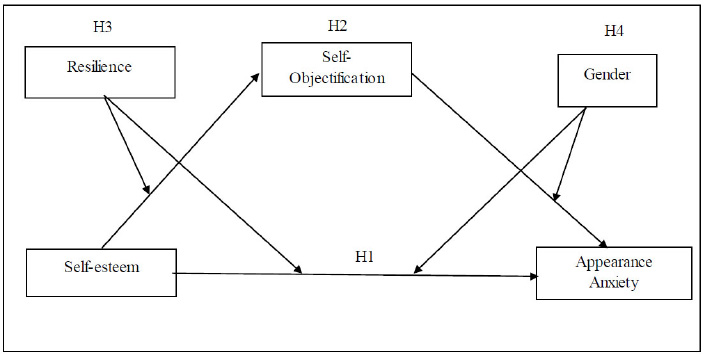

Social and cultural norms, particularly prevailing in Indian societies, influence appearance grooming, while social media usage drives thinness in women and muscularity in men [16, 24], substantially impacting appearance-related anxiety [4]. In this context, studying appearance anxiety among university students is so essential. It can negatively affect mental and physical health, contributing to decreased self-esteem, poor academic performance, the development of eating disorders, excessive exercise, depressed mood, body dissatisfaction, and reduced life satisfaction as well as well-being [7-11]. University students frequently evaluate and face criticism from others, particularly from peers, family, and relatives, regarding their physical appearance [43]. Hence, understanding the factors that protect against appearance anxiety and self-objectification in this population may aid in designing effective interventions to promote positive body image and healthy behaviors. Although previous studies have examined the relationships between self-esteem, appearance anxiety, and self-objectification [17, 19, 43], there is limited empirical research on the proposed model. The current study addresses some novel objectives and research questions, incorporating self-objectification as a mediator and resilience and gender as moderators in the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety (Fig. 1).

Key Objectives of the Present Study are as follows:

1. To validate the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety among university students in India.

2. To investigate the mediating effect of self-objectification on the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety.

3. To examine the moderating role of resilience and gender on both the mediational model (self-objectification) and the direct relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety.

Major Hypotheses:

H1: Higher self-esteem would negatively predict appearance anxiety.

H2: Self-objectification would mediate the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety of both men and women.

H3: Resilience would moderate the relationship between self-esteem, self-objectification, and appearance anxiety. That means individuals with high resilience would experience a stronger negative association between self-esteem and appearance anxiety, as well as between self-esteem and self-objectification.

H4: Gender would moderate the relationship between self-esteem, self-objectification, and appearance anxiety.

Hypothesized conceptual model predicting appearance anxiety —lines indicating both direct and indirect conditional effects.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Study Design

The present study followed a cross-sectional research design to conduct this research.

2.2. Participants

The sample size was calculated using a priori power analysis software, G* power 3.1.9.4, specifying a linear multiple regression model with an effect size = .10 while maintaining a p-value of 0.01 and a power level of .95 with 3 predictors. Output from G*Power specified that a minimum of 233 participants will be required. In the current study, 443 university students aged 18-24 years were selected through convenience sampling using both online and offline methods. The data was collected from Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, where the first author is affiliated as a research scholar. The data collection process was spanned from July 2023 to September 2023. In the current study, we adopted both online and face-to-face data collection methods, as the online approach is more accessible to a larger number of participants pool and less time-consuming than the face-to-face data collection method. In the online procedure, the authors shared the questionnaires through Gmail and WhatsApp. For face-to-face data collection, the authors personally approached each participant and invited them to voluntarily participate in the current study.

In this study, participants were selected based on pre-set criteria related to sociodemographic factors to control their influence. In addition, the convenience sampling technique is easily accessible, cost-effective, less time-consuming, and has greater feasibility for the research context and the researchers. However, it is important to note that this sampling may not represent the entire population. Therefore, the findings of this study should be interpreted with caution and may not be generalizable to whole populations. To reduce the selection bias, authors increased the sample size and statistical power of the study, making it more feasible to generalize the findings to the selected populations.

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSES)

The participants' self-esteem was measured using the 10 items of Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [44]. RSES consisted of a 4-point (1 = “strongly agree” to 4 = “strongly disagree”) Likert scale. It has five reverse score items such as 2, 5, 6, 8, and 9 (for example, “At times, I think I am no good at all”). The higher score of RSES indicates higher self-esteem, and the internal consistency using Cronbach’s α reported for all participants was 0.83, indicating a high internal consistency reliability.

2.3.2. Dahl Self-objectification Scale

The degree of self-objectification was assessed using the Self-Objectification Scale [45], which evaluates how one perceives his/her own body from another perspective. It is based on a 5-point Likert rating scale (ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”). For example, “How my body looks will determine how successful I am in life,” and “Being physically attractive will determine how many friends I have.” The internal consistency was acceptable, with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.82, indicating high reliability.

2.3.3. Appearance Anxiety Inventory (AAI)

The Appearance Anxiety Inventory (AAI) was used to measure the appearance anxiety of participants [46]. It has 10 items that measure specifically the cognitive and behavioral aspects of body image anxiety in general and body dysmorphic disorder (BDD). The participants were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 to 4 (0=not at all and 4=all the time). For example, “I compare aspects of my appearance to others” and “I discuss my appearance with others or question them about it.” In the present study, the internal consistency of the AAI was measured using Cronbach's α, which was reported to be .86, indicating high reliability.

2.3.4. Brief Resilience Scale (BRS)

The participants' resilience was measured using the Brief Resilience Scale [47]. The BRS has six items assessing the participants' resilience ability. The participants were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), for example, “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times.” In the current study, the internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α) of BRS was reported to be 0.85, suggesting a high and acceptable internal consistency reliability.

2.3.5. Sociodemographic Variables

To achieve the aim of the study, participants' age, gender, education, marital status, and sexual orientation have been recorded. Previous studies have reported mixed findings regarding the influence of sociodemographic factors on self-objectification and appearance anxiety. Although some studies suggest that variables such as age, gender, sexual orientation, and relationship status significantly influence these outcomes, others report no significant effects. To address this inconsistency, the present study controlled for demographic factors, including age, education, relationship or marital status, and sexual orientation, to assess their impact on self-objectification and appearance anxiety. Most of these factors were found to have no substantial effect. Additionally, gender was further analyzed as a moderating factor in the proposed model and treated as a dichotomous variable, with participants identifying as male (coded as 1) or female (coded as 2).

2.4. Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Department of Psychology at Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi. After obtaining ethical approval, the survey was conducted between July 2023 and September 2023, spanning three months. Written informed consent was obtained from each participant before their involvement in the study. Only those who voluntarily agreed to participate were included in the data collection. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time during the data collection process. Individuals aged 18–24 years were invited to participate through Google Forms and face-to-face interactions. For the online data collection method, questionnaires were distributed via Gmail and WhatsApp, ensuring that all responses would remain anonymous and confidential throughout the study. Written clarifications and explanations were provided in the questionnaires to aid completion. Participants were instructed to give genuine responses while answering the questions. The participants took an average of 20-25 minutes to complete all the responses. All the ethical protocols prescribed by APA were followed, and the study was conducted following the Helsinki Declaration for involving human participants. After reading an information sheet and receiving consent, participants completed sociodemographic details related to age, gender, education, marital status, and sexual orientation, followed by appearance anxiety, self-esteem, self-objectification, and resilience.

2.5. Statistical Analyses

All statistical procedures were performed using IBM SPSS version 26.0, Amos statistical version 23.0 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA), and SPSS PROCESS Macro Model 29 [48]. The normality data distribution was confirmed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, confirming a fair distribution across sample groups. To ensure the internal consistency and reliability of all scales, we tested the Cronbach α. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the mean and standard deviation of the included variables. Pearson correlations were tested to examine the relationship between all scale variables. The mediational analysis and model fit were performed using Amos statistical version 23. The conditional process analyses (moderated mediational analysis) were performed using SPSS PROCESS Macro software (Model 29). SPSS PROCESS Macro model 29, developed by Andrew F. Hayes, is a valuable tool for researchers conducting moderated mediation analysis within a triadic variable framework. It evaluates whether the indirect effect of an independent variable (X) on an outcome variable (Y), mediated through a third variable (M), is influenced by moderators (W and Z). This model is especially useful for examining complex relationships where both mediation and moderation processes coexist, providing deeper insights into the conditional process pathways.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Demographic Details of the Participants

Through the data cleaning, 6 participants were removed using Mahalanobis distance [49]. The final sample consisted of 437 participants aged 18 to 24 years (Mage = 21.89; SD = 1.59). Among them, 234 participants (53.5%; Mage = 22.22; SD = 1.37) were male, and 203 (46.5%; Mage = 21.58; SD = 1.42) were female. Additionally, 5.03% were high school students, 4.2% were in intermediate courses, 59.5% were enrolled in bachelor’s programs, 17.85% in master’s programs, and 13.5% in professional and technical courses. Among the 437 participants, 322 (73.68%) were unmarried; 10.98% identified as homosexual, 20.14% as bisexual, and 66.8% as heterosexual.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations among the selected continuous variables. The inter-correlations among variables were performed with SPSS version 26. The bivariate correlations indicate that self-esteem has a negative correlation with appearance anxiety (r = -.40, p <.01) and self-objectification (r = -.26, p <.01), while self-esteem was positively associated with resilience (r =.26, p <.01). Similarly, appearance anxiety was negatively associated with resilience (r = -.38, p <.01) and positively associated with self-objectification (r =.53, p <.01). Additionally, resilience was negatively associated with self-objectification (r = -.28, p <.01).

| - | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. SE | 22.68 | 6.5 | 1 | -.40** | -.26** | .26** |

| 2. AA | 18.21 | 8.28 | -.40** | 1 | .53** | -.38** |

| 3. SO | 46.07 | 8.21 | -.26** | .53** | 1 | -.28** |

| 4. Res | 19.32 | 5.82 | .26** | -.38** | -.28** | 1 |

3.3. Mediational Analyses-hypotheses Testing (H1-H2)

In the present study, we examine the model fit indices for all metric scales using Amos statistical version 23. To assess the goodness of fit, we used the normed model chi-square (χ2/df), with values of < 3 considered to be a good fit [50] and up to 5 considered to be an adequate fit. We also examine the Steiger-Lind root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% CI to provide correct model proximity. The RMSEA value of the mediational model is 0.055, which indicates a good fit. The Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) suggests a level of relative fit, with a value close to >.95 for adequate fit, and above >.80 is acceptable [50]. In the present mediational model, goodness of fit indices like TLI (.948) and CFI (.956) are considered a good fit.

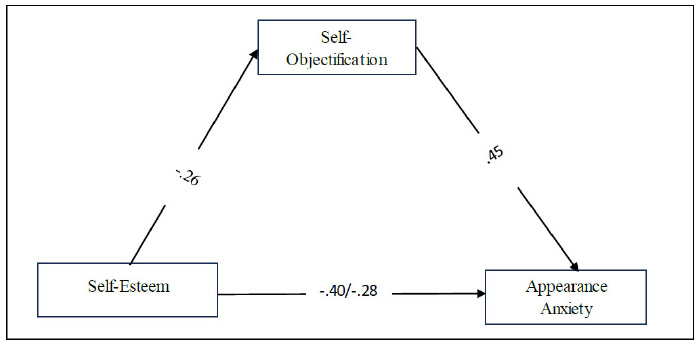

SPSS Amos version 23 was used to analyze the mediational model described in our hypothesis (H1-H2). The results of our mediational analysis are shown in Fig. (2). In the predictor-mediator relations, high self-esteem negatively predicted self-objectification, β = -.33, SE (standard error) =.06, 95% CI = [-.45, -.22]. The mediator-criterion relationship, self-objectification, yielded a positive correlation with appearance anxiety, β =.46, SE =.04, 95% CI = [.38,.54]. The direct relationship between self-esteem was directly and positively associated with appearance anxiety, β = -.36, SE =.05, 95% CI = [-.47, -.26]. The results of this study revealed that the direct relationship between higher self-esteem was negatively associated with appearance anxiety (H1), and self-objectification significantly mediated the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety (H2), indirect effect = -.15, SE =.03, 95% CI = [-.21, -.10].

3.4. Moderated Mediational Analysis (H3-H4)

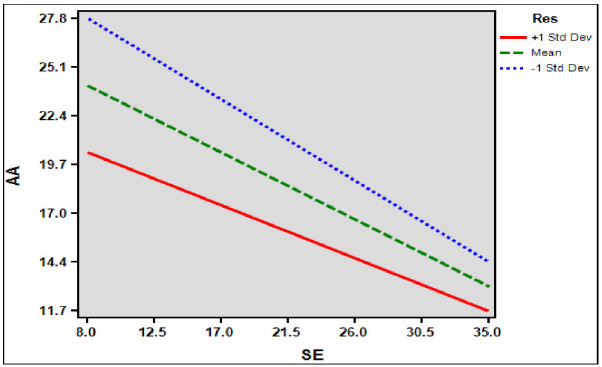

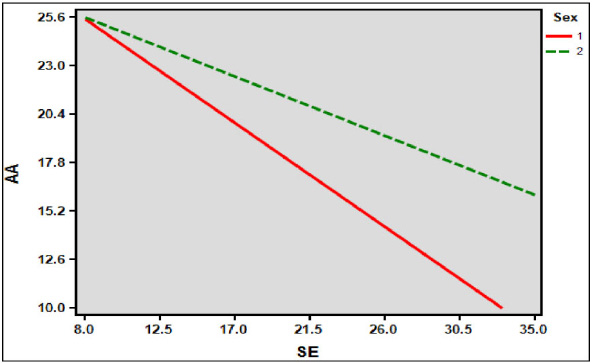

To test hypotheses 3 and 4, we used SPSS PROCESS Macro model 29, suitable for examining multiple moderators and a single mediator. The predictor-mediator analysis showed that the interaction effect of self-esteem and resilience was significantly associated with self-objectification [b = -.03, 95% CI = (-.05, -.01), t (1, 433) = -3.11, p <.001]. Similarly, predictor criterion analysis revealed that the interaction effect of self-esteem and resilience was significantly associated with appearance anxiety [b =.03, 95% CI = (.01, 0.4), t (1, 429) =3.45, p <.001]. However, the moderation effect of gender in the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety was insignificant [b =.07, 95% CI = (-.13, .26), t (1, 429) =.68, p > .50]. Additionally, the moderation effect of gender in the relationship between a mediator-criterion relationship (self-objectification and appearance anxiety) was

Shows the direct and indirect effect of self-esteem on appearance anxiety via self-objectification.

Interaction of self-esteem and resilience on appearance anxiety (+1SD, Mean, and -1SD).

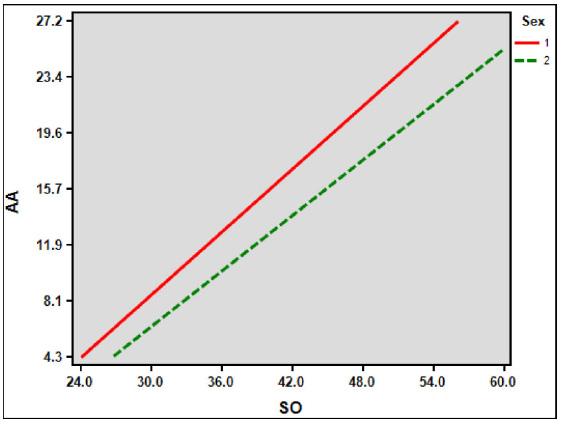

Interaction effect of self-esteem and gender (1 = male, 2 = female) on appearance anxiety.

insignificant [b = -.06, 95% CI = (-.34, .22), t (1, 429) = -.42, p >.05]. To improve clarity, we illustrated the interaction effect of resilience and self-esteem on appearance anxiety in Fig. (3), showing that lower levels of resilience and self-esteem are associated with higher appearance anxiety among university students. Fig. (4) demonstrates that higher self-esteem is negatively associated with appearance anxiety in both males and females. Additionally, the graphical representation of the mediator-criterion relationship in Fig. (5) suggests that, as self-objectification increases among students, appearance anxiety also rises similarly across genders.

Interaction effect of self-objectification and gender (1 = male, 2 = female) on appearance anxiety.

| Direct Effects | Indirect Effects |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | Effects | SE | 95% CI | Effects | SE | 95% CI | |

| Res*M | -1 SD | -.47 | .08 | -.63, -.30 | -.06 | .04 | -.14, .03 |

| Res*F | -1 SD | -.40 | .08 | -.56, -.24 | -.05 | .04 | -.13, .02 |

| Res*M | Mean | -.31 | .07 | -.45, -.16 | -.15 | .04 | -.22, -.09 |

| Res*F | Mean | -.24 | .07 | -.38, -.10 | -.13 | .05 | -.23, -.05 |

| Res*M | +1 SD | -.14 | .09 | -.32, .03 | -.25 | .05 | -.36, -.14 |

| Res*F | +1 SD | -.08 | .09 | -.25, .10 | -.22 | .08 | -.38, -.08 |

Table 2 shows the conditional direct and indirect effects of self-esteem and self-objectification on appearance anxiety, accounting for resilience and gender as moderating factors. Upon assessing multiple degrees of resilience, including -1SD, the mean level, and +1SD, we noticed that a low level of resilience (-1SD) or levels lower than -1SD did not significantly influence the described relationships. However, higher levels of resilience showed considerable moderating effects on both the direct and indirect correlations between self-esteem and appearance anxiety, independent of gender.

4. DISCUSSION

This study investigated the mediating roles of self-objectification and moderating roles of resilience and gender in the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety in 437 university students. The findings suggested that self-esteem was negatively associated with appearance anxiety, and this relationship was significantly mediated by self-objectification. Additionally, the interaction effect of self-esteem and resilience significantly reduced the negative effects of both appearance anxiety and self-objectification across genders. This research presents a theoretical framework to understand the underlying mechanisms by integrating self-esteem, appearance anxiety, self-objectification, resilience, and gender. It also offers recommendations for therapies aimed at reducing appearance anxiety and self-objectification among university students through increasing self-esteem and resilience.

The results of the mediational analysis confirmed the H1 that self-esteem is negatively related to an experience of appearance anxiety in both men and women. This finding, in line with the previous serial mediational analysis, suggests that the negative effect of appearance anxiety on social anxiety is lower via the mediational effect of esteem [4]. More specifically, individuals with higher self-esteem have lower levels of appearance anxiety [51]. In addition, this finding corresponds with prior research that examined the relationship between low self-esteem and its detrimental effect on health outcomes such as depression, anxiety, self-objectification, and psychological distress [19, 52, 53].

The testing of hypothesis 2 showed that the indirect effect (indirect effect = -0.15) of self-esteem via self-objectification was lower than the direct effect on appearance anxiety. The findings suggested that self-objectification significantly mediated the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety by amplifying the negative effect of appearance anxiety in university students. Additionally, the conditional process analysis revealed that the direct effect of self-esteem on appearance anxiety was significantly moderated by resilience across genders. Although no prior study has specifically examined the mediational role of self-objectification in the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety, some related findings can support these current findings. For example, one study examined the serial mediation effect of social appearance anxiety and body image on the relationship between self-objectification and well-being, revealing that self-objectification positively predicted social appearance anxiety and body image concerns, which in turn led to lower well-being among adolescents and young adults [54]. Similarly, another study with 291 female university students reported that self-esteem significantly mediated the relationship between self-objectification and social physique anxiety; and self-objectification is negatively associated with self-esteem while positively related to social physique anxiety [17]. It highlights how cultural pressures and the objectification of physical appearance affect mental well-being, particularly among adolescents and young adults. Adhering to societal norms related to appearance and attractiveness can negatively affect self-esteem. When self-esteem is low, it can increase social physique anxiety, causing adolescents to feel self-conscious and anxious about their physical appearance in social or academic situations.

Moreover, the self-objectification theory suggests that appearance anxiety develops from individuals internalizing societal standards, further influencing their self-evaluation process [21]. This internalization process often leads to poor self-esteem and can contribute to mental health disorders, including depression and anxiety. Previous empirical studies based on the Self-Objectification Theory suggested that when people objectify their bodies, they are more susceptible to experiencing appearance anxiety and act in ways that try to meet conventional beauty standards [55, 56]. A mediational model reported that self-objectification is positively correlated with appearance-dependent self-worth, leading to higher levels of appearance anxiety and, ultimately, lower self-esteem [19]. Building on this theory, the current study revealed that appearance anxiety is negatively associated with both self-esteem and resilience among adolescents and young adults.

The moderating analysis of resilience has been largely focused on the area of psychological difficulty and mental health [57] but less on the area of self-objectification and appearance anxiety [58]. Based on the previous findings [57], the primary objective of the present study was to investigate the moderating function of resilience between self-esteem and appearance anxiety among men and women via self-objectification. The results of this study showed that resilience moderated the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety in both genders. It could be attributed to the emphasis on the physical appearance of females and the societal demands for unrealistic beauty standards. A physical appearance obsession is also promoted among males, although to a lower level than women, driving men to confront several negative consequences.

Furthermore, this study found that gender neither significantly moderates the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety nor the relationship between self-objectification and appearance anxiety. These findings align with previous research [43], which reported that self-objectification directly and negatively predicts self-esteem and indirectly via appearance anxiety, while the moderating role of gender is insignificant [43]. Similarly, a cross-sectional study found an insignificant gender effect in the relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety among secondary school students [41]. Some recent studies acknowledged that girls are experiencing greater appearance anxiety than boys [2, 59]. One empirical study suggested that the widespread use of social media platforms (both image- and text-based), where individuals of both genders engage in social comparisons with others, may heighten appearance-related concerns [2]. A systematic review has noted that individuals of both genders are vulnerable to body image-related concerns [60]. This review also highlighted the significant role of culture in shaping body image perceptions, with Western cultures predominantly driving for thinness, whereas non-Western cultures uphold differing ideals. A phenomenological study on 35 Indian women aged 18–40 years suggested that body image experiences in women comprised some key themes such as beautiful, thin, or fair body, internalization, and body image management. Each of these themes negatively affects women's health and is associated with higher body monitoring, which further leads to unhealthy behaviors and body dissatisfaction [61]. Another study conducted on 511 young male Indian students (aged 18–25 years) revealed that 34.44% of students reported a moderate to marked level of body image dissatisfaction, and it was higher among underweight men compared to obese men. They also suggested that socio-cultural pressures, including family, peers, and media, significantly influence the internalization of muscular and thin body image ideals [62].

Most of the studies indicate that females place greater importance on their physical appearance and body shape, and feminist theorists highlight that females' bodies are objectified in society as objects to be looked at. Therefore, a woman's body image is influenced by others' opinions about her. The socio-cultural theorists advocate this viewpoint that societal expectations and ideal beauty standards encourage females to be attractive and invest more in physical appearance, which can be associated with body dissatisfaction and other psychological issues [63]. Another study suggested that although both males and females suffer from appearance-related concerns, they define them differently [15]. Males give a higher emphasis on male-related physical characteristics/mostly focus on muscularity-type qualities. Muscularity is a sign of power, so any man who fails to achieve an ideal muscular body can develop a negative body image [15, 63]. For example, they highly focus on height, weight, arms, shoulders, chest, legs, thighs, muscular tone, and hairstyle. While females place greater emphasis on facial appearance, hair color, hairstyle, weight, waist, stomach, buttocks, legs, hips, and breasts [15].

4.1. Limitations and Future Suggestions

This study has some limitations that need to be incorporated in future studies. First, the sampling method relying on a convenience sample may create selection bias that may restrict the findings for generalization to whole populations. Thus, future research must apply probability sampling methods to reduce the selection bias. Second, the use of self-report measures introduces the possibility of social desirability bias, where participants might respond in a manner they perceive as socially acceptable, leading to potential inaccuracies in the data, which may be reduced through applying indirect questioning and randomized response techniques and using this as a control variable. Third, the cross-sectional and correlational research methods prevent concluding causal relationships among included variables. Therefore, future studies should incorporate these variables in experimental and longitudinal research designs or may examine them in different models. Fourth, several variables not measured in this study such as family dysfunction, self-compassion, attachment styles, social connectedness, and stressful events which may significantly influence the present relationships. Therefore, future research should include these factors for a better understanding of the complex interplay between self-objectification and appearance anxiety. Lastly, interventional research is essential to determine effective therapeutic methods that can increase resilience and self-esteem while reducing self-objectification and weakening the relationship between self-objectification and appearance anxiety. Understanding how specific interventions affect these variables can lead to more targeted and effective treatments for individuals suffering from higher levels of appearance anxiety.

4.2. Implications

This study offers important theoretical and practical insights into self-esteem, appearance anxiety, and self-objectification among university students. Theoretically, it contributes to the literature by providing a conceptual framework that integrates self-esteem, resilience, self-objectification, and appearance anxiety. The findings indicate that self-esteem and interaction with resilience significantly reduce appearance anxiety among university students. This model also demonstrated that the moderating effect of resilience is highly beneficial in reducing the negative effect of appearance anxiety, while self-objectification exacerbates it. According to the Self-Objectification Theory, societal and internalized beauty standards lead to greater appearance-related anxiety. Our findings also contribute to this theory by revealing self-objectification as a potential mediator between self-esteem and appearance anxiety. Practically, these findings suggest that programs related to fostering resilience can be beneficial in educational settings to reduce appearance anxiety. Universities should offer resilience-focused workshops and counseling that can address and counter unrealistic beauty standards by boosting students' capacity to manage appearance pressures.

This study also has some important findings that can be helpful for mental health practitioners, educators, policymakers, and students. Mental health providers/mental health clinicians should focus on university students who are more sensitive to appearance anxiety and provide early intervention strategies to address body esteem and social appearance anxiety. Programs aimed at enhancing self-esteem and resilience are essential. Several interventional studies acknowledge that interventions focused on resilience significantly improve positive psychological factors and reduce negative symptoms. For example, an interventional study provided resilience-based psycho-educational interventions to college students through four-week sessions, each lasting two hours [64]. The authors found that psycho-educational intervention significantly improved resilience, coping strategies (i.e., higher problem solving, lower avoidant coping), self-esteem, self-leadership, positive affect, and lower scores on depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and negative affect of the experimental group compared to the control group. Similarly, another interventional study provided a group intervention to college students focusing on resilience and coping. This study suggested that group intervention successfully reduces stress, anxiety, and depression and significantly improves coping strategies and interactions with peers [65]. Moreover, schools, institutions, and workplaces should integrate such activities and organize workshops to address these areas. Building higher self-esteem can significantly improve psychological well-being and reduce appearance anxiety, highlighting the need for diverse counseling strategies to foster self-esteem. Strengthening family and peer support systems through community-based initiatives and support groups can provide crucial social support for individuals experiencing high levels of appearance anxiety. Additionally, interventions targeting self-objectification, such as media literacy classes, can empower students to critically analyze and reject unattainable beauty ideals conveyed on social media.

Furthermore, policymakers should concentrate funding for mental health activities targeting social appearance anxiety, boosting mental health awareness, and resources regarding psychological support, particularly among adolescents and young people. Continued research is needed to further understanding of the dynamics of appearance anxiety, self-esteem, and resilience, with longitudinal studies providing deeper insights and informing more effective interventions. By applying these implications, participants can establish supportive environments that weaken the negative effects of appearance anxiety and self-objectification and increase the student's self-esteem and resilience.

CONCLUSION

In this study, we examined the association between self-esteem and appearance anxiety, focusing on self-objectification as a mediator and resilience and gender as moderators among adolescents and young adults. The findings suggested that individuals with higher self-esteem are less prone to being affected by appearance anxiety and self-objectification, while higher self-objectification is linked to greater appearance anxiety. The inverse relationship between self-esteem and appearance anxiety highly increases when self-esteem and resilience also combinedly affect appearance anxiety. Although higher self-objectification amplifies the detrimental effect of appearance anxiety on mental health, high resilience appears to buffer these effects across genders. Therefore, educational institutions should provide resilience-building and media literacy programs to help students manage appearance anxiety. Additionally, therapeutic and social support services can boost self-esteem and reduce susceptibility to beauty pressures.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

N.B.: Contributed to writing the manuscript, data collection, data analysis, and interpretation of the results; S.K.: Contributed to manuscript preparation, revision, and proofreading.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| AAI | = Appearance Anxiety Inventory |

| AMOS | = Analysis of Moment Structures |

| BDD | = Body Dysmorphic Disoder |

| CFI | = Comparative Fit Index |

| CI | = Class Interval |

| IRB | = Institutional Review Board |

| Mage | = Mean Age |

| RES | = Resilience |

| RMSEA | = Root mean square Error Approximation |

| RSES | = Rosernberg Self-Esteem Scale |

| SD | = Standard Deviation |

| SE | = Self-Esteem |

| SO | = Self-Objectification |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| TLI | = Tucker-Lewis Index |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the Department of Psychology at Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India (Number = Psych/Res/Sep.2021/E/5).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article will be available from the corresponding author [N.B] upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The first author wants to acknowledge his supervisor Dr. Kavita Pandey for her enormous support and guidance in this research. The second author wants to acknowledge her parents & family members for providing their constant supports and participants for their active participation.