All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Psychosocial Account of the Social Added Value of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations: A Participatory Study

Abstract

Background

The psychosocial perspective of the Social Added Value (SAV) is a valuable account of the social impact of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations (NPVOs). This is because it recognizes the economic impacts of NPVOs. However, the existing top-down operationalization of SAV still needs the integration of a bottom-up perspective (i.e., NPVOs’ members' perspective).

Objectives

Following a participatory research approach, the study seeks to complement the existing psychosocial perspective with bottom-up perspectives on SAV.

Methods

The study uses concept mapping, a participatory stakeholder-driven process, to generate a framework of SAV on a sample of NPVO managers (N = 105).

Results

The results of the participatory study reveal that the elements characterizing NPVOs’ SAV act in a circuit of benefits comprising the contextualization of the individual in the community and contributing to the lives of people in and around the community. This bottom-up operationalization of NPVOs’ SAV comprises six main benefits, namely (a) state and territory, (b) care and awareness, (c) create and valorize relationships, (d) community and social promotion, (e) well-being and (f) self-determination, and local activation.

Conclusion

The findings of the study provide indications to complement the psychosocial perspective of SAV and its implications for theory and practice. Notably, these findings appear to reflect the ecological perspective of community psychology. As such, they offer a starting point for tailoring interventions to support and promote communities and NPVOs.

1. INTRODUCTION

Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations (NPVOs) play a pivotal role in enriching the social capital of communities by bringing a series of social and economic benefits [1-3]. NPVOs navigate within communities and confront unique and particularistic challenges to address neglected struc-tural needs. They operate and cooperate in community partnerships as value-oriented organizations for effectively facilitating, managing, or proving local community needs. According to the 2022 State of the World’s Volunteerism annual report, it is estimated that 6.5% of the working-age people worldwide engage in NPVOs, which act as central actors in alleviating social issues, providing services, and mirroring the capacity of communities [4]. Having an open eye on individual and community needs, NPVOs bring seismic change by marking the interstices of social structures and pointing towards the limits of communities while renewing and serving them [3, 5, 6].

While it is not surprising that NPVOs grapple with maintaining the social capital of communities, there remains a significant gap in understanding and operationalizing NPVOs actual contributions [7-10]. In contemporary society, classical profit evaluation models imbue NPVOs with ideas of social impact by referring to the logics of accountability and cost-benefits. As value-driven organizations with a series of extra-economic impacts, the majority of NPVOs fail to provide evidence of their activities and benefits to communities as NPVOs struggle to adhere to such economic evaluation criteria [1, 2]. In this latter sense, Mannarini et al. (2018) have recently proposed the term Social Added Value (SAV), loosely defined as the series of relational values that NPVOs create [11]. The authors did so by following the relational sociology perspective on the added social value according to which NPVOs are organized settings for relational purposes that realize public goods and social capital of communities per se [12, 13]. From the psychosocial perspective, SAV “consists in maintaining, restoring, and regenerating relational goods in communities” [14, p. 9], and it represents a potential indicator of NPVOs’ promotion of social capital [15, 16].

The psychosocial model of the SAV model represents an initial step for NPVOs to value their social impact, thanks to the recognition of the series of tangible and intangible benefits. Yet, its operationalization is still open to revisions [11]. In this study, we sought to complement the psychological perspective of SAV as an indicator of NPVOs social impact by using a participatory mixed-method approach, i.e., the concept mapping approach [17, 18], to explore the perspectives of NPVOs. The current operationalization of SAV considers a distinction between internal relational goods (i.e., those generated and experienced within an NPVO) and external relational benefits (i.e., those that one NPVO provides to the community). While this operationalization offers a standardized approach to evaluation practices, it lacks the integration of stakeholder perspectives into it. That is the perspective of NPVO’ members, particularly NPVOs managers, on their social impact remains overlooked. Realizing a shared operationalization of SAV among academics and non-academics can help in understanding how existing NPVOs situate in their community beyond the clarity of their goal and organizational purpose [1, 4, 11]. Moreover, integrating the psychosocial lens via a participatory perspective on how NPVOs articulate the social value of their organizations can be particularly relevant for NPVOs striving to find concrete ways for evaluation practices. NPVOs’ managers’ perspectives on SAV appear relevant because of their position in leading members and defining initiatives within communities. In parallel, complementing the current perspective on SAV NPVOs with managers' perspectives can benefit managers themselves. Operationalizing their community-level approach can help NPVOs’ managers to mobilize their initiatives best, and integrate values, competencies, and skills in supporting individuals and the community.

In the rest of the article, we proceed as follows. First, we present our methodological approach. This section outlines the concept mapping method for participatory research in psychology. We continue by presenting the procedure and data analytical strategy. In the following section, we present SAV’s resulting operationalization, which is later discussed in the last section. Here, we conclude by discussing SAV while offering theoretical and practical contributions.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. The Concept Mapping Approach

To pursue our objective, we realized a participatory action-research study with a group of managers of NPVOs as lay researchers by following the methodological approach of the concept mapping approach. Concept mapping is a systematic mixed-method approach gathering the community members’ narratives [19] while engaging with them around a certain topic of interest, e.g., the notion of SAV. It follows six main research stages: preparation, idea generation, structuring, representation, interpretation, and utilization [17, 20]. Despite its mixed-method nature, this approach gives primacy to the narratives of the participants while the quantitative part is subsumed [19].

In the first stage (i.e., preparation), the research group defines the community sample (e.g., NPVO managers) and develops one or more stimuli to engage the community about research questions. A stimulus is termed a “focus prompt” as it consists of incomplete sentences in a “fill-in-the-blank” style, which is used to elicit diverse ideas within the group of participants. These are later submitted to the participants in the second stage (i.e., idea generation). Using both traditional paper and pencil or online questionnaires, participants are asked to complete the sentence with a minimum of three to a maximum of five words or sentences. This allows the collection of different and separate ideas from the participants' perspectives. Then, once data are collected, the second stage of idea generation requires researchers to do a general scrutiny of the answers in which they discard uncertain terms and combine synonyms to arrive at a maximum of 100 [17, 21].

The third stage (i.e., structuring ideas) represents an initial participative qualitative analysis aiming to organize the ideas collected and their importance in defining the topic of interest. This analysis is made by a small group of community members (from 10 to 15, Lantz et al., 2019) who had previously taken part in the idea generation stage. These participants operate as lay researchers and are instructed to realize the sorting task. The group is given a number and a card on each of which a single idea is listed, and individually, the lay researchers have to group the ideas according to the meaning they attach to them.

In the fourth stage (i.e., representation), the resulting groups of cards/ideas are quantitatively analyzed by the research group using multivariate statistics (i.e., multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis) to depict the cluster of ideas and map the elements of the topic under investigation. Notably, individual results of lay researchers' sorting task (i.e., third stage) are analyzed using multidimensional scaling to map the ideas and create a single aggregated map of the ideas. This produces an x,y coordinate for each idea based on the conceptual similarity among each idea. Then, the cluster analysis is applied to the x,y coordinates to partition the ideas into clusters of the related concepts.

The fifth and sixth stages (i.e., interpretation and utilization) involve interpreting and using the resulting materials. In the fifth stage, the research group analyzes the results of the multidimensional scaling and cluster analysis to gather the meaning of the resulting clusters. Lastly, results are utilized during the last stage by discussing them with community members to plan community-based program development [22].

2.2. Participants

One hundred and five volunteers (36% women, 65% over 60 years old, 63% retired, and 76% having experience volunteering of more than ten years) took part in the first stage of idea generation. Ninety-one percent of participants identified as directors or managers of the NPVOs, while the rest were part of the management committee. Following the Italian National Statistics Institute classification of the volunteering sector, the majority of the sample were managers of NPVOs operating on social assistance and civil protection (44%), healthcare providers (26%), and culture and recreation (24%). The rest of the sample operates in educational organizations, environmental issues, national and international cooperations, and social cohesion.

Ten participants (50% female, 100% over 60 years old, and retired with at least ten years of volunteering experience) participated in the stage of structuring ideas. For the interpretation-utilization stage, we organized a focus group in which n = 10 NPVO managers took part (20% female, 90% over 60 years old, and retired with at least ten years of experience in volunteering).

Participants were recruited via the Service Centre for Volunteering (Centro di Servizio per il Volontariato – CSV) of Verona, and we submitted paper and pencil questionnaires during the idea generation stage. Participants received the questionnaire during the annual NPVOs’ network assembly. In the questionnaire, the participant could indicate a contact (e-mail address) if available to be involved in the subsequent stages of the research. These were later invited for the third stage of the structuring ideas and the interpretation-utilization stage, during which we operated in the spaces of the CSV network.

The study has been approved by the ethical committee of the University of Verona (code: 2023_12) according to the declaration of Helsinki.

2.3. Procedure

2.3.1. Preparation

Three in-person sessions were held to prepare the focus prompt. Five researchers with expertise in concept mapping, community psychology, and volunteering took part in each session. All sessions started with collecting ideas on realizing the focus prompt following our research question on defining the SAV of NPVOs. Considering that the notion of SAV implies a series of community benefits, one focus prompt relating to the benefits of NPVOs was chosen. However, the notion of SAV implies words such as “social,” “community,” and “value,” these words were not used in order to let the focus prompt open as much as possible so as not to bias the replies of the participants. The focus prompt contained positive elements of volunteering: “In my view, the benefits of volunteering are…”.

2.3.2. Idea Generation

Data collection for the second stage of idea generation consisted of a paper and pencil questionnaire proposed to NPVO managers during the assembly of the local network. After reviewing the study description and giving written informed consent, participants completed demographic questions (gender, age, role in the NPVOs, see the participants description in the Participants section) and “filled in the blank” the focus prompts. No compensation was given to participants for their time and input, and participation was voluntary.

2.3.3. Structuring the Ideas

For structuring the ideas stage, n = 10 participants (i.e., lay researchers) who previously took part in the idea generation stage were involved. Sessions began with collecting informed consent and demographics. Then, a set of cards reporting the ideas was delivered to each participant to sort into piles by theme in a way that could make sense to them. Lay researchers had to work individually on their cards. The sorting concluded with them submitting their responses to the researchers.

2.3.4. Representation

Once all the previous stages have been completed, the quantitative analyses of the sorted ideas have been conducted. Two parallel multivariate statistical analyses have been run, namely multidimensional scaling analysis followed by hierarchical cluster analysis, to convert the sorted ideas into a visual representation. As noted, multidimensional scaling is used to group each idea on a bidimensional map (x,y) by calculating the distance between each idea following the sorting of the participants. In turn, the ideas that participants have grouped are likely to appear close on the bidimensional map. That is, the idea's location is computed based on how often ideas are sorted together. Ideas with closer positions are those more often sorted into the same group by multiple participants. Notably, the increase in distance between ideas is due to the fact that certain ideas are not often (or ever) sorted together by participants [22, 23]. Afterward, the hierarchical cluster analysis applies to the points of each idea on the map to reduce the number of ideas by considering their conceptual similarities [23]. The cluster analysis computes from the minimum of 1 cluster to N clusters occurs when each idea is considered an individual cluster.

This analysis has been conducted using the open-source R code IdeaNet [22]. Results have been evaluated by considering a) the goodness of fit of the resulting model and b) the meaning of the model. The fit index covers the model's stress level; namely, higher levels of model stress indicate a poor structure, while lower levels of model stress indicate a good and reliable structure in which ideas can be grouped together [23]. Model stress varies between 0 to 1, and when the stress value is < .305, it is considered acceptable when the number of ideas sorted does not exceed 100 (the stress value for the present study is .278) [24]. Ultimately, an interpretative task is necessary for the researchers to choose the appropriate number of clusters “in order to have a clear understanding of the issue” (p. 307) [22].

2.3.5. Interpretation & Utilization

According to concept mapping indications at the end of the fourth stage, the researchers interpret the resulting clusters and decide which, among acceptable models, is the most adequate. This evaluation has been made taking into account the number of ideas per cluster and their adequacy to represent the topic investigated [22]. One cluster solution has been selected, and one focus group has been organized with a small proportion of participants who took part in the third stage. N = 16 NPVO managers attended the focus groups and shared their interpretations and views on the resulting ideas and cluster. The sessions lasted two hours, and only one researcher was involved. This interpretation stage also initiated the utilization stage as the second part of the focus group was used to evaluate how the notion of SAV can help develop community-based program development.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Idea Generation

In the first step of idea generation, 241 focus prompt responses were provided by NPVOs managers. According to the literature, lists of ideas containing a maximum of 100 is appropriate for the third stage of structuring the ideas [17, 21]. Consequently, two researchers who participated in the preparation stage reviewed all the ideas collected (N = 241) separately, and redundant or similar ideas collapsed. In some cases, they combined or revised statements for clarity. Finally, n = 79 ideas resulted.

3.2. Structuring Ideas & Representation

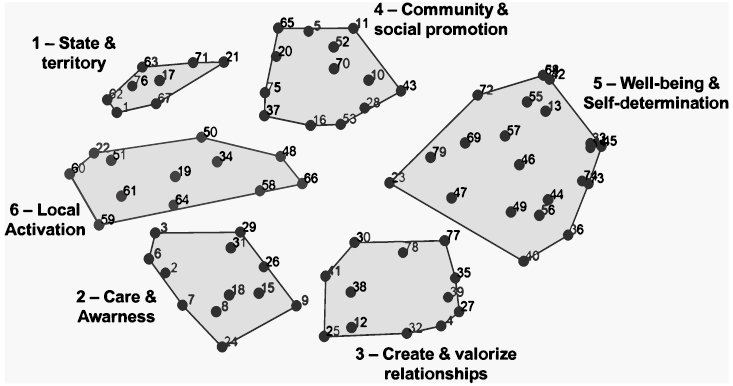

Starting from these ideas (n = 79) elaborated by the researchers, participants (i.e., lay researchers) provided 10 independent groups of ideas’ organization. Six clusters of responses were identified through multidimensional scaling and hierarchical cluster analysis (Fig. 1). Examples of ideas for each cluster are presented in Table 1. Since the stress value of the present study is 0.2778 and less than 0.305 [24], we can expect less than a 1% probability that the data are randomly organized.

| Cluster 1: State and Territory |

| 1. Understanding the needs that policy often fails to address |

| 17. Understanding institutional needs and reaching out to those in need |

| 21. Connecting the individual and society |

| 62. Strengthening the services of the territory |

| Cluster 2: Care and Awareness |

| 2. Caring for the person and the environment |

| 6. Realizing some social situations |

| 7. Socializing and aggregating |

| 8. Welcoming and listening to others |

| Cluster 3: Create and Valorise relationship |

| 35. Creation of ties, even if brief and occasional |

| 38. Making one's own contribution |

| 39. Empowering retirees to be engaged |

| 41. Giving relief to situations of hardship and loneliness |

| Cluster 4: Community and Social promotion |

| 37. Social growth |

| 43. Dispelling differences between human beings |

| 52. Committing to a just cause in the interest of citizens |

| 65. Promoting democracy |

| Cluster 5: Well-being and Self-determination |

| 57. Occupying one's time for others |

| 68. Realizing oneself beyond work |

| 69. Giving back what one has received |

| 74. Personal satisfaction |

| Cluster 6: Local activation |

| 19. Promoting social cohesion |

| 22. Filling territorial gaps in services |

| 34. Creating a solidarity network in the territory |

| 50. Providing social assistance |

3.2.1. Cluster 1: State and Territory

The first cluster that defines SAV represents the cluster with 10.12% of the ideas collected. The ideas in this cluster lead back to broader community participation and to anything that NPVOs can lead to in terms of contributing to the community where local authorities and the state fail to contribute. In addition, SAV comprises the value of NPVOs in being linked to the local territory as well as in representing a resource to respond to the needs of the community to which NPVOs belong. For example,

The concept map: The chosen 6-cluster solution.

this cluster comprised ideas describing the benefits of NPVOs as the capacity to understand the needs of communities, which may be often neglected by national or local policies (ideas example, “1. Understanding the needs that policy often fails to address”). This adherence to the local needs overlooked by the state results in activities aimed at providing and fostering services in the local context (“62. Strengthening the services of the territory”).

3.2.2. Cluster 2: Care and Awareness

The second cluster (15.18% of ideas collected) refers to the dimensions related to the elements that make NPVOs contribute to social capital and community resilience. Ideas of this cluster appear to decline with the gerund to describe the permanent practice of the NPVOs. That is, cluster 2 contained ideas referring to the practice of care NPVOs for people and the environment (ideas example, “2. Caring for the person and the environment”). Such a practice of care departs from being aware of the others’ needs and the NPVOs’ preoccupation with realizing an open and inclusive service (ideas example, “8. Welcoming and listening to others”). These actions span from the awareness of the community’s needs to creating solutions offering care and support. Independently of their personal views and stories, people of the NPVOs recognize themselves as inherent to one community, a feeling that turns into a constant engagement in collective actions for the community.

3.2.3. Cluster 3: Create and Valorise Relationship

In parallel to cluster 2, the third cluster comprises 16.45% of the ideas that describe additional actions that NPVOs provide to the community, which ultimately contribute to the community’s social capital and resilience. To empower the social capital of one community, NPVOs create relationships with internal members and external members of their NPVOs. For example, managers identified NPVOs as a space in which marginalized individuals can find an inclusive and open space for meaningful relationships (ideas example, “41. Giving relief to situations of hardship and loneliness”). In parallel, NPVOs offer opportunities for individuals to be engaged (ideas examples, “39. Empowering retirees to be engaged”). As such, relationships are valued by allowing people to engage in activities that contribute to the flourishing of the community. Interestingly, this cluster probably reflects the awareness of the pivotal value of community relationships.

3.2.4. Cluster 4: Community and Social Promotion

The fourth cluster is also made up of 16.45% of the ideas. It encapsulates ideas that lead to the more general civic dimension, enclosing several facets. First, NPVOs contribute to the community's growth, which appears in the creation of social values. Unsurprisingly, managers indicated that the various actions that NPVOs make result in inclusive and extensive services that ultimately make one's society grow. Connected to such an effort, including and promoting actions within the community results in realizing democratic values. With respect to this, NPVOs’ managers show to have a clear idea of their role in the community by emphasizing their work as value-based (ideas example, “52. Committing to a just cause in the interest of citizens”) to realize humanitarian goals (“65. Promoting democracy”).

3.2.5. Cluster 5: Well-being and Self-determination

The fifth cluster suggests that NPVOs' contribution to social capital and community resilience, as described by the notion of SAV, also occurs via the promotion of individual members. The fifth cluster includes the highest number of ideas (26.58% of ideas collected), which refer to everything that constitutes the earnings derived from being part of an NPVO. It embodies all those ideas regarding the possibility that individuals can contribute to their own well-being and self-determination via participation in NPVOs. Indeed, NPVOs’ managers define their work as volunteers as an opportunity for self-realization beyond other sources of meaning (e.g., love or work) (idea examples, “68. Realizing oneself beyond work”). Such a contribution results from the individual's choice to participate in collective actions that also lead to well-being (ideas example, “74. Personal satisfaction”).

3.2.6. Cluster 6: Local Activation

The sixth and last cluster encompasses 10.12% of the ideas and refers to everything constituting how NPVOs activate a community regarding present and future needs. Ideas of cluster 6 are quite self-evident. For example, the NPVOs’ managers generated ideas that are included in this cluster, which refer precisely to the empowerment of relationships within communities by NPVOs (ideas example, “19. Promoting social cohesion”). However, local activation is not only a matter of promotion in general of relationships but rather in offering concrete services (ideas example, “50. Providing social assistance”). Then, as in clusters 1 and 4, the sixth cluster reminds us how NPVOs adhere to the local community needs, recognize the discomfort made by the lack of institutional support, and realize such awareness by creating the possibility for activating the community both in terms of present needs of the community and future needs caused by external factors. In turn, local activation describes the possibility offered by NPVOs to maintain democratic values and build the capacity of a community, which can ultimately manifest in creating a better future.

4. DISCUSSION

In contemporary society marked by discourses of social impact and evaluation practices, the psychosocial perspective on SAV represents a potential tool for NPVOs’ accounting. Indeed, it offers a standardized approach characterized by the operationalization of NPVOs’ series of relational benefits. Nevertheless, this perspective has so far adopted predominantly a top-down lens in which the stakeholder perspective remains overlooked. Following the impetus to integrate the current perspective with a bottom-up approach, we realized a concept mapping study to capture the perspectives of NPVOs’ managers on NPVOs’ Social Added Value. Extending the relational nature of benefits, findings revealed that NPVO managers’ perspective on SAV includes six core groups of values. They are routed in the importance of giving centrality to community needs and the need for change (Cluster 1). The centrality of community needs is parallel to caring for structural problems (Cluster 2) and realized in creating worthy actions that promote the community (Cluster 3 and 4). In this, NPVOs not only work as community activators (Cluster 6) but also their members receive in return a series of benefits (e.g., self-determination and well-being, Cluster 5).

4.1. Theoretical Contributions

Although our study followed a bottom-up perspective, the results of the mixed method study can offer initial indications on how to complement the psychosocial conceptualization and model-based measure of SAV.

In the literature, the psychosocial perspective of SAV follows an operationalization based on the series of internal and external relational factors that NPVOs produce. This operationalization is based on the sociological understanding of SAV as the production of relational goods, which in turn generate public goods and can be considered indicators of the social capital of communities [11-13]. Accordingly, the psychosocial operationalization covers different relational constructs derived from community psychology literature, which define the elements composing SAV structure. Taken together, NPVOs’ SAV is represented by the symmetry between relational goods that NPVOs provide to their members and those provided to the community [11, 14]. From the theoretical point of view, it is worth noting that our bottom-up perspective on SAV does not completely overlap with the psychosocial understanding of SAV [11, 14]. That is, the cluster map indicates that NPVOs’ SAV is better understood as a circuit of benefits rather than the symmetry of two groups of benefits of NPVOs. Moreover, these benefits are not only to be understood as relational in nature but rather as different factors spanning from individual level aspects (i.e., Clusters 2 and 5) to community and society (i.e., Clusters 1, 3, 4, and 6). Accordingly, NPVOs’ members gain social awareness (Cluster 2), well-being, and self-determination (Cluster 5) [25], which appear to be individual elements that act in a systemic way with community-level elements such as social cohesion (Cluster 3), collective action, and community activation (Cluster 1, 4 and 6) [26, 27]. The emerged clusters and their circular relation from the individual to the community indicate that SAV can be better understood as positioned in contextualizing the individual in the community and in society [27, 28]. Ultimately, while we can agree that SAV is “precisely the emergent effect of the agential, interactive, and systemic reflexivity” [13 p. 20], it is also important to recognize the socially added values of each single element composing it.

Following this inception, the six clusters can be read in terms of community psychology literature in order to offer a more extensive view of the elements composing SAV that can complement the existing perspective. First, Cluster 1, “State & Territory,” refers to the very idea that NPVOs situate their actions in a context lacking resources and services. On the surface, this may appear quite obvious; that is, NPVOs situate their activities in a specific local context and, as such are confronted with structural problems and needs of such contexts. However, accounting for the social value of NPVOs also requires the recognition of their very social stance, i.e., their social responsibility and vision [29]. Second, Cluster 2, “Care & Awareness,” Cluster 5, “Community & Social promotion,” and Cluster 6, “Local activation”, seem to recall the literature on participation with a specific emphasis on the type of participatory action, i.e., civic engagement [30], but reminds to the notion of community care [31]. Clusters 2, 5 and 6 highlight how volunteers engage in activities for solutions, offering care and support due to their awareness of social and individual needs. This appears to be in line with the categorization of the concept of participation, particularly with an emphasis on civic engagement as a form of active involvement in issues that affect people’s lives and impact the larger community [30]. Third, Cluster 3, “Create & Valorise relationships”, largely overlaps with the dimensions of SAV identified in Mannarini et al. (2018) “Quality of internal relations” and “Quality of external relations”, yet it also adds that NPVOs’ create not only positive internal and external relationships but also relational systems in which they are valued and sustained. Lastly, Cluster 5, “Well-being & Self-determination”, emphasizes the “huge array of subjective benefits” [32] p. 7969] and recognizes it as part of SAV. Cluster 5 reminds us of the role of NPVOs in supporting the well-being of their members as individuals can find a space to experience and perceive meaning in their lives, particularly via senses of beneficence, autonomy, competence, and relatedness [33]. This recalls the wide-established perspective of the Self-Determination Theory [34], and suggests that SAV can also represent the extent to which NPVOs provide occasions for well-being and individual flourishing. These findings indicated that the SAV model could be complemented by more refined constructors but also include additional constructs in its current operationalization, such as volunteers’ well-being.

Furthermore, these results overlap with current categories of debate on social capital within community psychology [35]. Accordingly, the clusters show that SAV includes bouncing back the community to structural needs (Clusters 1) [36], connecting with community members (Cluster 3) [37] while reinforcing and renewing protecting factors of the community (Clusters 4 and 6) [38]. This main finding does not provide any specific answer to the unresolved scholarly tension on whether NPVOs’ are activators of social capital or whether it is the social capital brought by the presence of NPVOs that activates its members [9, 16, 39, 40]. In the literature, there are multiple perspectives on social capital, and relational sociology refers to SAV as characterizing social capital. This is because NPVOs produce public goods and services due to investment in social relations. Then, social capital is the social added value of relations and represents the capacity to generate public goods thanks to NPVOs’ production of relational goods [12, 13]. In our study, we noted that as NPVOs confront community needs, managers may discount the use of terms such as capital and benefits often coopted by economic values [41, 42]. Conversely, they describe a series of individual and community-level elements in which SAV and social capital reflect the ideal of change according to which community well-being and social impact cannot be realized individually but rather relationally with proper participatory social engagement [43, 44]. In speculative terms, we can argue that participation and sense of community represented in our clusters foster social empowerment [45] and social capital [9].

Lastly, our bottom-up understanding of SAV aligns with the systemic-ecological approach of community psychology [27, 28, 46]. This is due to the emphasis of SAV on creating, thanks to internal and external NPVOs’ relationships, and improving the resources of communities and influencing their future. This is also in line with the idea of relational sociology from which the concept of SAV has originated. On the one hand, the ecological perspective of community psychology emphasizes the need for understanding people in the community context and the community context itself. In this, people are agentic responders to their environments, and as such attention is paid to the transitions from individual to community (i.e., community life of individuals) and vice versa (i.e., social and cultural contexts of communities). The ecological approach is central for actions for preventive interventions as well as for promotion interventions [46]. On the other hand, the relational sociology approach emphasizes the idea that relations characterize social capital, which in turn generates and valorizes public goods [12, 13]. Thus, the emerging representation of SAV from the perspectives of NPVOs’ managers can be enticing for scholars in the field. It adds that NPVO managers harbour a less robust notion of the benefits of NPVOs, which includes the capacity to foster social impact by anchoring to the community [47-49]. Accordingly, NPVOs’ SAV is relational, social, and political in nature, realized as the creation of an agenda for community members to fight against social injustice, and psychology can put effort into sustaining such an agenda [6, 50]. The resulting circular operationalization of NPVOs' SAV seems to be able to aid in identifying, containing, and going one step further, generating a community-level approach that is able to nourish and sustain social capital and community resilience.

4.2. Applied Implications

Our bottom-up perspective on SAV suggests that NPVOs’ benefits act in a circuit and span from individual-level dimensions to community and society-level elements. In turn, it is important for NPVOs to understand more about which aspects are at the individual, community, and societal levels and how their social value can be recognized, sustained, and promoted. For example, NPVO managers can draw on the insights offered in this study to represent their benefits and define their actual contributions to their NPVOs’ members and communities. That is, NPVOs’ managers can use our 6-cluster solution to describe their organizations and contributions toward communities narratively. This can make stakeholders and beneficiary communities more aware of the change being driven by NPVO activities and, in turn, increase potential engagement and interest in future developments [32].

Equally, focusing on the elements of the cluster map can help to realize interventions supporting SAV’s elements. For example, clusters 3, “Create and Valorise Relationships,” and 4 “Community and Social Promotion” remind us to the ideas of Mannarini et al. (2018) that NPVOs can promote vocational training programs to work on relational dimensions among volunteers, but also training aimed at fostering positive external relations by fostering volunteers’ sense of social responsibility towards users, institutions, and stakeholders. This can be the case for activities that promote organizational identification among volunteers, as well as initiatives for socialization between volunteers and community members. Operating at these levels can be important for sustaining and promoting SAV so that NPVOs’ members can be mobilized and supported in their voluntary engagement.

In parallel, clusters 1 “State and Territory,” 2 “Care and Awareness,” and 6 “Local activation,” may be used by NPVOs’ managers as lenses to identify and interpret their initiatives in the local context. While this may seem obvious, classifying their work can support NPVO managers in identifying potential areas of improvement (e.g., recruiting new volunteers and attracting financial resources) and, in turn, promoting their SAV. Similarly, Cluster 5 “Well-being snf Self-determination,” reminds us to the possibility of conducting internal surveys on NPVOs’ volunteers’ experience and perceptions of well-being. Evidence-based knowledge in this respect can help managers to understand their SAV but also design volunteers’ activities in order to reflect their basic psychological needs.

Nevertheless, our bottom-up perspective reflects also the level of applied implications. That is, rather than attempting to create universal practices, we highlight the importance of considerations for tailoring interventions to the needs of different NPVOs and communities by using our findings as an interpretative framework. For example, practitioners might use our cluster map via narrative approaches in order to mobilize and account for the SAV [45]. NPVOs could use our findings to narratively describe and map their contributions to the community, identifying beneficiaries, institutions, volunteers, and staff involved, as well as activities or experiences. Such an intervention can lead to additional insights and useful situated knowledge on which to base more specific practices. Simultaneously, working with our cluster map can also enhance volunteers’ self-esteem and their perception of community service self-efficacy [33].

4.3. Limitations and Future Research

The present study is the first of its kind to examine NPVO's SAV via a participatory research approach and, as such, it is intended to be exploratory. Although it provides an initial basis for research-conducting and practice-orienting, our findings have to be interpreted with some caution as a few limitations must be acknowledged. First, the specific local context and the variations and differences among NPVOs’ managers imply that our findings result from multiple perspectives that may not represent the general population of volunteers, particularly managers of NPVOs, and the experiences of other cultural and organizational settings. Moreover, our sample was characterized by the presence of only NPVOs managers of a specific age (65%, over 60 years old) and occupational status (63% retired). Likewise, our findings may not reflect the perspective of individuals engaged in emerging forms of volunteerism (e.g., episodic and online volunteering) who may have a different account of SAV due to the different temporal and spatial character of such forms of volunteerism. Taken together, these limitations inform that our findings cannot be considered as reflecting the global perspective of NPVOs’ SAV but rather as a situated perspective that combines multiple variations and differences of NPVOs of specific local contexts. As such, our findings are not generalizable to the wide population involved in volunteerism, to the different contexts, to the variety of NPVOs, and to emerging forms of volunteerism. For example, younger populations may show different accounts of SAV, and narratives of non-manager volunteers and non-volunteers (i.e., community members) may not overlap with those of NPVOs’ managers. Differences can also be observed in different cultural settings as specific local contexts may reflect different accounts of NPVO value. Lastly, individuals engaged in emerging forms of volunteerism may have different narratives of their experiences, requiring additional attention in future research.

Nevertheless, this is the first exploratory study aiming at advancing a bottom-up perspective, and these limitations do not invalidate its findings but rather inform future research. For future research on SAV, our cluster map can be used as an interpretative framework that is open to extension due to different populations and cultural and organizational settings. Researchers might conduct a series of concept mapping studies with different populations (e.g., young adults), in different local contexts, focusing on specific areas of NPVOs or on different forms of volunteerism (e.g., traditional, episodic, and online volunteering). Such a large comparative investigation can be realized across different regions and involving a more diverse sample (e.g., NPVOs’ managers vs volunteers) to reach a broader understanding of SAV in NPVOs.

Second, we restricted our method to the use of concept mapping without comparing our results with standardized measures of SAV [11, 14]. Although this implies that our findings are not without risk of biased perceptions of the social value of NPVOs, concept mapping is also a mobilizing method that fosters awareness, social responsibility, and self-efficacy. Moreover, our purposes were exploratory in order to gain a bottom-up perspective on SAV via the narratives of NPVO managers. Ultimately, this limitation does not affect the implications of our results per se, yet it may suggest that future research could involve a parallel methodology to explore NPVOs' SAV. For example, our findings can be used for larger scrutiny using our clusters for scale development [51, 52], which can be implemented in addition to existing instruments.

CONCLUSION

This study sought to integrate the psychosocial perspective on NPVOs’ SAV by employing the concept mapping approach. This allowed us to realize a participatory understanding of SAV in which we identified the elements characterizing NPVOs' SAV through the lens of a group of NPVOs’ managers. These elements are positioned in a circuit of benefits comprising the contextualization of the individual in the community and society. Our findings offer an initial common ground that can help extend the repertoire of evaluation practices of NPVOs. Moreover, these results can help psychologists who aim to assist communities in developing tools, frameworks, and community‐based interventions.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

A.M.M., F.T. and F.C.: Study conception and design; C.P.: Methodology; A.M.M. and F.T.: Draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| SAV | = Social Added Value |

| NPVOs | = Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study has been approved by the ethical committee of the University of Verona, Italy (code: 2023_12).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article is available in the IRIS platform at: https://hdl.handle.net/11562/1147908.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gladly acknowledge the active group of the members of CSV of Verona, the participants of our study, and the community of scholars who are studying volunteerism. We particularly thank Cinzia Brentari, Daria Rossi, and Sandro Stanzani for their comments and support of our work.