All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Bullying Victimization and its associated Factors among Adolescents in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia: A Cross-sectional Study

Abstract

Introduction

Bullying is a pervasive issue among adolescents, impacting their psychological and social well-being. In Indonesia, where adolescent bullying is widespread, there is limited research on the factors influencing bullying victimization, particularly within specific cultural contexts. This study aims to examine the factors associated with bullying victimization among Indonesian adolescents.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted with 295 high school students in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. Data were collected using self-reported surveys, including the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (OBVQ) and the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). Associations between bullying victimization and demographic, emotional, and behavioral factors were analyzed using chi-square tests, independent t-tests, and logistic regression.

Results

Approximately 21.4% (n=63) of participants were identified as victims of bullying, with verbal bullying (31.5%), social exclusion (18.6%), and rumor-spreading (30.8%) being the most common types. Logistic regression analysis showed significant associations between bullying, victimization, and gender (OR = 0.438, 95% CI = 0.223–0.860, p = 0.016), with males at a lower risk. Emotional symptoms in the borderline range were associated with reduced odds of victimization (OR = 0.282, 95% CI = 0.086–0.293, p = 0.036), as were borderline conduct problems (OR = 0.241, 95% CI = 0.083–0.700, p = 0.009).

Discussion

The findings reveal gender-specific victimization patterns consistent with Indonesia's cultural context, where patriarchal structures may influence bullying dynamics. The inverse relationship between borderline psychological symptoms and victimization risk suggests complex protective mechanisms that may operate differently within Indonesian collectivist frameworks compared to Western contexts. These results contribute to understanding bullying dynamics in understudied populations, though the single-site design and cross-sectional nature limit generalizability and causal inference.

Conclusion

Bullying victimization in Indonesian adolescents is closely linked to gender, parental marital status, and emotional or behavioral factors. These findings highlight the need for culturally adapted interventions focused on relational aggression and support for at-risk students.

1. INTRODUCTION

Adolescence represents a critical developmental phase characterized by significant neurobiological, psychological, and social changes that shape long-term health trajectories. During this period of rapid development, bullying emerges as a pervasive threat to adolescent well-being, manifesting as intentional aggressive behavior characterized by power imbalances and repeated negative actions over time [1, 2]. Epidemiological evidence underscores the global prevalence of adolescent bullying and its public health impact. Recent meta-analyses have documented widespread psychological, emotional, and behavioral consequences that can persist into adulthood [3, 4]. In Indonesia, approximately 19.9% of adolescents report experiencing several instances of bullying [5, 6]. Victims often exhibit increased rates of anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation, alongside behavioral issues such as academic disengagement, interpersonal conflicts, and adoption of sedentary lifestyles [3, 4, 7, 8].

Research has established associations between victimization and increased substance use, as adolescents often resort to smoking, alcohol consumption, and drug use as coping strategies [7, 8]. Evidence also highlights the impact on sleep patterns, particularly sleep loss due to worry (SLOW), which creates a cycle of emotional vulnerability and impaired recovery [9]. These effects show particular severity among younger adolescents (≤14 years) and exhibit gender-specific patterns, with females showing higher susceptibility to anxiety and depression outcomes [10, 11].

While preliminary prevalence data exists, the literature shows limitations in explaining the complex relationships between cultural, demographic, and psychosocial variables that shape bullying patterns in Indonesian educational environments. Previous studies have primarily used descriptive methods without examining the multidimensional factors that influence victimization risk, particularly the relationship between emotional-behavioral symptoms and bullying vulnerability. The influence of gender-specific practices, parental educational attainment, and occupational status in shaping victimization experiences remains inadequately explored within Indonesia’s social framework [12-14].

Demographic analyses have identified age and gender as important factors in bullying victimization. Younger adolescents, particularly those aged 14 years or younger, show increased vulnerability, possibly due to power differentials relative to older peers [10, 11]. Gender analyses reveal distinct patterns, with females showing higher rates of anxiety, depression, and social isolation following victimization experiences [15, 16].

The relationship between mental health status and bullying victimization presents a complex dynamic. Pre-existing mental health challenges, including anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem, may increase vulnerability to bullying through impaired social functioning and reduced self-advocacy [17, 18]. This vulnerability is often worsened by difficulties in help-seeking behavior [19]. Victimization frequently intensifies existing mental health symptoms, creating a cycle of psychological distress and social marginalization that may be further complicated by maladaptive coping strategies like social withdrawal, academic disengagement, and substance use [20, 21].

While substantial research has examined bullying victimization in Western contexts, the present study addresses gaps in understanding this phenomenon within Indonesia’s sociocultural landscape. Unlike previous studies that primarily focus on prevalence rates or isolated risk factors, this study offers three distinct contributions to the literature. First, it provides a comprehensive examination of the relationships between demographic variables, mental health indicators, and bullying patterns specific to Central Kalimantan adolescents, an understudied population. Second, it explores how borderline emotional and behavioral symptoms relate to victimization risk, providing insights into subclinical psychological factors that may influence peer dynamics. These distinctions enable a more nuanced understanding of bullying mechanisms within Indonesia’s educational environment, potentially informing culturally appropriate intervention strategies.

This study aimed to address critical gaps in understanding bullying victimization within the Indonesian context by examining the relationships between mental health status, demographic characteristics, and socioeconomic factors. This investigation seeks to clarify the specific mechanisms through which these variables influence bullying dynamics, with the ultimate goal of informing evidence-based prevention strategies that address root causes at individual, family, and community levels.

1.1. Theoretical Framework

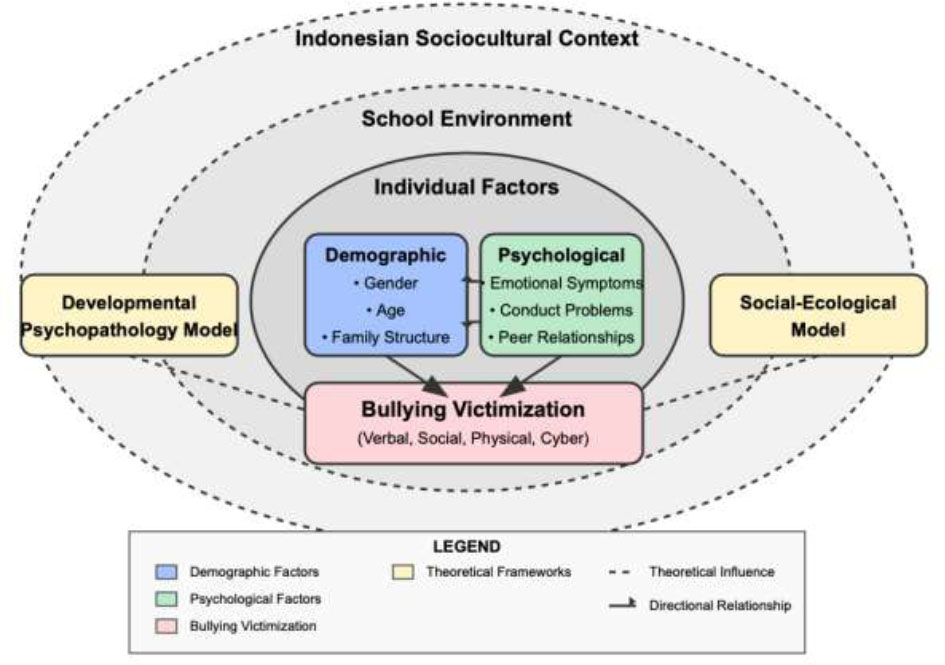

Fig. (1) illustrates the theoretical framework used in this study. This study is anchored in an integrated framework that combines developmental psychopathology with social-ecological models to explain the relationships between psychological functioning and bullying victimization.

Theoretical framework of bullying victimization among indonesian adolescents.

The developmental psychopathology perspective views bullying as a manifestation of maladaptive social interactions that both influence and are influenced by individual psychological trajectories [22]. This framework posits that emotional and behavioral symptoms represent critical factors in victimization vulnerability, operating within multilayered ecological systems that encompass individual, interpersonal, and contextual domains.

The inclusion of emotional symptoms as a focal construct derives from the symptom-driven model of victimization [23], which suggests that internalizing symptoms may function as antecedents that signal vulnerability to potential perpetrators. Meta-analytic evidence supports this premise, documenting significant relationships between emotional symptoms and subsequent victimization, with reciprocal effects observed across developmental stages [24].

Similarly, the investigation of conduct problems as a correlate of victimization is grounded in the social skills deficit model [25], which proposes that externalizing behaviors may alter peer dynamics and social positioning, thereby modifying victimization risk trajectories. Empirical evidence supports this proposition, with longitudinal studies demonstrating associations between conduct problems and victimization experiences across diverse cultural environments [26].

The integration of these psychological constructs with demographic variables reflects an ecological systems approach [27], which recognizes that bullying dynamics emerge from complex interactions between individual characteristics and contextual factors. This theoretical synthesis provides a structured framework for examining the multifaceted determinants of victimization within Indonesia’s unique sociocultural landscape, where family structures, gender dynamics, and educational environments operate within distinctive cultural parameters.

This multidimensional theoretical foundation informs both the selection of variables and the analytical approach employed in the current investigation, facilitating a comprehensive examination of the pathways through which demographic and psychological factors influence victimization vulnerability among adolescents in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design

This cross-sectional correlational study examined the connections between sociodemographic factors, mental health, and bullying victimization among adolescents in Indonesia.

2.2. Setting and Samples

The study took place in September 2024 at a public senior high school in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia. To obtain a representative sample from each grade level, stratified random sampling was used, with all first- through third-year students eligible to participate. The sample size was determined using G*Power software (version 3.1.9.7; Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Germany) based on a correlation coefficient of 0.25, a significance level of 0.05, and a statistical power of 0.99, which required at least 228 participants. The selected correlation coefficient of 0.25 represents a methodologically sound estimate derived from prior meta-analytic evidence, including Reijntjes et al., who documented correlations ranging from 0.18 to 0.41 between internalizing symptoms and peer victimization, and Schoeler et al., who reported similar effect magnitudes (r =0.20-0.36) when examining psychological functioning and victimization experiences [23, 24]. In total, 295 students were included in the final analysis, yielding substantial data to support the study’s aims [28].

2.3. Measurement and Data Collection

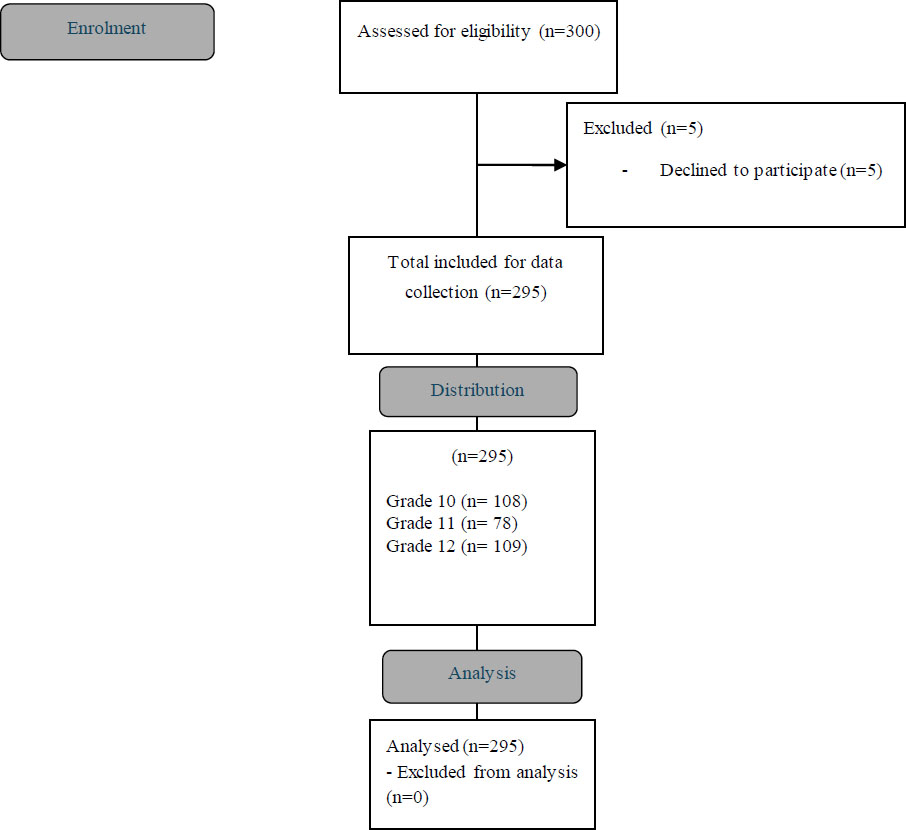

Data were collected through a survey comprising a demographic questionnaire (including gender, age, grade level, residential status, parents marital status, parental education, and parental occupation), the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ), and the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (OBVQ-R). The data collection process is depicted in Fig. (2).

2.4. Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) was used to assess emotional and behavioral disorders. Originally developed by Goodman [29], the SDQ has been adapted into Indonesian by several studies [30, 31] and endorsed by Indonesia’s Ministry of Health to screen for Emotional and Behavioral Problems (EBPs) among Indonesian adolescents. This tool includes 25 items covering five subscales relevant to EBPs: emotional problems (e.g., “Often complains of headaches”), conduct problems (e.g., “Often has temper tantrums or hot tempers”), hyperactivity (e.g., “Constantly fidgeting or squirming”), peer problems (e.g., “Rather solitary, tends to play alone”), and prosocial behavior (e.g., “Considerate of other people's feelings”). Responses are rated on a three-point scale (0 = not true, 1 = somewhat true, 2 = extremely true), and each subscale score is calculated by summing the related item scores, ranging from 0 to 10. The instrument showed high reliability, with an overall Cronbach’s α of 0.863. Each subscale also demonstrated acceptable Cronbach’s α values: emotional problems (0.804), conduct problems (0.486), hyperactivity (0.753), peer problems (0.513), and prosocial behavior (0.852).

Flow diagram of the observational study.

2.5. Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (OBVQ)

The OBVQ is a self-report questionnaire designed to assess peer bullying incidents in school over two months [32, 33]. This study focused solely on items related to victimization (10 items), where students could indicate if they had experienced bullying (e.g., “How often have you been bullied at school in the past couple of months?”). The survey included nine specific forms of bullying: (1) teasing or name-calling; (2) social exclusion; (3) physical aggression, such as hitting, kicking, or pushing; (4) rumor-spreading; (5) theft or property damage; (6) threats; (7) racially motivated comments; (8) sexual remarks or gestures; and (9) cyberbullying. Additionally, a tenth item allowed students to report any other types of bullying that had not been suggested by the previous categories [32]. Responses were collected using a five-point scale ranging from 0 to 4 (0 = no incidents in the last two months, 1 = once or twice, 2 = 2–3 times per month, 3 = once per week, and 4 = several times per week). As per Solberg and Olweus, the threshold for identifying a student as a victim versus a non-victim was set at “2-3 times per month.” Previous research has validated the OBVQ, demonstrating internal consistency values between 0.8 and 0.9 [34].

2.6. Data Analysis

We conducted our analysis using the chi-square test for categorical variables and the independent t-test for continuous variables. In analyzing correlates, we first examined univariate associations between independent variables and bullying victimization. Potential confounding variables were identified through both theoretical considerations and preliminary bivariate analyses. Variables demonstrating associations with victimization at p<0.25 in univariate analyses were incorporated into the multivariate model. The multivariate model construction proceeded through sequential block entry, with demographic variables (age, gender, grade level, residential status, parental marital status) entered in the initial block, followed by psychological variables (emotional symptoms, conduct problems, hyperactivity/inattention, and peer relationship problems) in the second block. Multicollinearity was evaluated using variance inflation factors (all VIF<2.5), confirming parameter stability. Odds Ratios (OR) with 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) were computed, with two-tailed p-values and an alpha level of 0.05 marking significance. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 22.0; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

2.7. Ethical Considerations

Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants, as well as from the parents or legal guardians of minors. Additionally, informed assent was received from the adolescents, confirming their understanding and agreement to take part. The study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Health Sciences, Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang, in accordance with WHO 2011 standards and CIOMS 2016 guidelines (Approval No. E.4.d/079/KEPK/FIKES-UMM/X/2024). All procedures strictly followed the approved protocol, safeguarding participants’ rights and welfare throughout the research. A structured referral pathway was established in collaboration with the school counseling department, facilitating expedited access to psychological services for students reporting significant distress. This support framework included follow-up procedures conducted two weeks post-participation to assess delayed emotional responses potentially triggered by study involvement. All support services were provided at no cost to participants, and confidentiality protocols were designed to protect student privacy while ensuring access to appropriate intervention resources.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Participants Characteristics

The study sample consisted of 295 Indonesian adolescents aged 15 to 19 years. As shown in Table 1, the majority of participants were 17 years old (36.9%), followed by those aged 16 (30.8%) and 15 (24.7%), resulting in a mean age of 16.28 years (SD = 0.94). The gender distribution was nearly equal, with 50.2% female and 49.8% male participants. In terms of grade levels, 36.9% were in grade 12, 36.6% in grade 10, and 26.4% in grade 11. Most participants came from families where the parents were married (89.2%), while 10.8% had divorced parents.

| Variable | Category | f | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 15 | 73 | 24.7 |

| 16 | 91 | 30.8 | |

| 17 | 109 | 36.9 | |

| 18 | 19 | 6.4 | |

| 19 | 3 | 1.0 | |

| Mean ± SD = 16.28 ± 0.94 | |||

| Gender | Female | 148 | 50.2 |

| Male | 147 | 49.8 | |

| Class level | 10 | 108 | 36.6 |

| 11 | 78 | 26.4 | |

| 12 | 109 | 36.9 | |

| Parents marital status | Married | 263 | 89.2 |

| Divorced | 32 | 10.8 | |

| Residential status | With parents | 259 | 87.8 |

| Living alone | 14 | 4.7 | |

| Living with another family | 22 | 7.5 | |

| Paternal education | Elementary school | 38 | 12.9 |

| Junior high school | 39 | 13.2 | |

| Senior high school | 150 | 50.8 | |

| College | 68 | 23.1 | |

| Maternal education | Elementary school | 49 | 16.6 |

| Junior high school | 51 | 17.3 | |

| Senior high school | 141 | 47.8 | |

| College | 54 | 18.3 | |

| Paternal occupation | Civil servant | 44 | 14.9 |

| State employee | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Private employee | 54 | 18.3 | |

| Self-employed | 74 | 25.1 | |

| Retired | 9 | 3.1 | |

| Unemployment | 7 | 2.4 | |

| Outsourcing | 2 | 0.7 | |

| Others | 104 | 35.3 | |

| Maternal occupation | Civil servant | 36 | 12.2 |

| Private employee | 13 | 4.4 | |

| Self-employed | 26 | 8.8 | |

| Retired | 1 | 0.3 | |

| Unemployment | 127 | 43.1 | |

| Others | 92 | 31.2 | |

Table 1 also highlights that the majority of students (87.8%) lived with their parents, with smaller percentages living alone (4.7%) or with another family (7.5%). Parental education levels varied, with half of the fathers (50.8%) and a significant portion of mothers (47.8%) having completed senior high school. Other educational levels for fathers included elementary school (12.9%), junior high school (13.2%), and college (23.1%), while for mothers, 16.6% completed elementary school, 17.3% junior high school, and 18.3% completed college.

Parental occupations were diverse. As shown in Table 1, fathers were primarily self-employed (25.1%), civil servants (14.9%), or private employees (18.3%), while a significant portion (35.3%) had various other types of employment. A smaller number of fathers were unemployed (2.4%), retired (3.1%), state employees (0.3%), or worked in outsourcing roles (0.7%). In contrast, the largest percentage of mothers were unemployed (43.1%), followed by those in civil service (12.2%), self-employment (8.8%), private employment (4.4%), and various other occupations (31.2%).

3.2. Description of Bullying Victimization

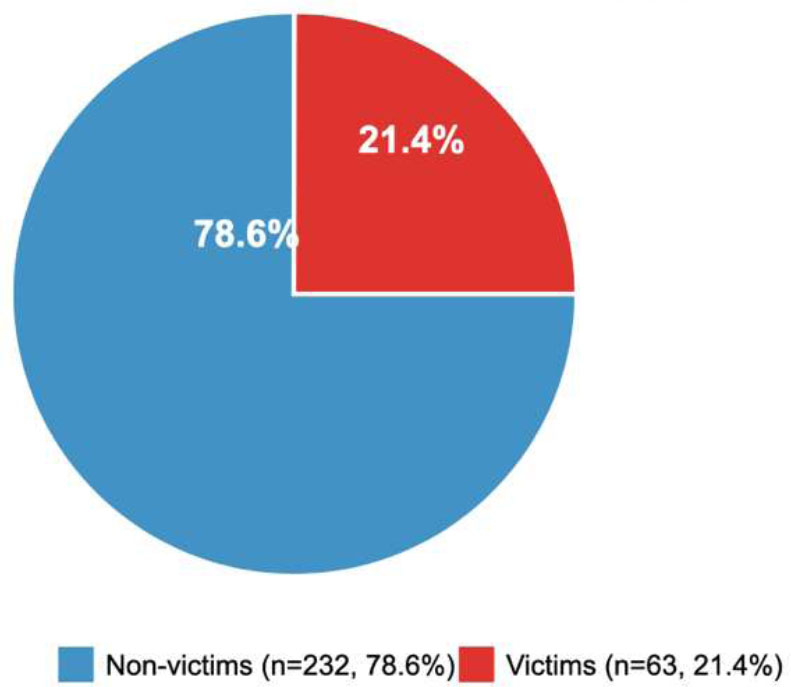

Fig. (3) provides an overview of bullying victimization status among the 295 participants. Of the total sample, 21.4% (63 students) were classified as victims of bullying, while the remaining 78.6% (232 students) were non-victims. This indicates that approximately one-fifth of participants reported experiencing bullying, reflecting a notable prevalence of victimization within this adolescent population.

Table 2 details specific bullying experiences based on the typologies reported over the past two months. Verbal bullying, including mean names, teasing, or mocking, was reported by a significant portion of the sample. While 54.9% reported no incidents, 31.5% experienced verbal bullying once or twice, and smaller proportions experienced it more frequently, with 4.1% reporting incidents 2-3 times per month, 1.4% once per week, and 8.1% several times per week. Social exclusion was also prevalent, with 75.3% reporting no occurrences, 18.6% experiencing it once or twice, 2.7% reporting 2-3 instances per month, and 3.4% experiencing it several times per week.

Physical bullying, such as being hit, kicked, or pushed, was less common, with 95.9% reporting no incidents, 3.1% experiencing it once or twice, and 1.0% experiencing it several times per week. Rumor-spreading was relatively more common, with 63.7% reporting no incidents, 30.8% experiencing it once or twice, 2.4% 2-3 times per month, and 2.7% several times per week (Table 2).

Theft or property damage affected a small portion of participants, with 85.4% reporting no incidents, 3.1% experiencing it once or twice, and only 0.3% experiencing it more frequently. Similarly, threats or coercion were rarely reported, with 96.3% experiencing no incidents, 3.1% experiencing it once or twice, and 0.3% experiencing it more frequently. Racial bullying was uncommon, with 86.4% experiencing no incidents. However, 9.8% reported it once or twice, and smaller percentages reported it 2-3 times per month (1.0%), once per week (0.7%), and several times per week (2.0%) (Table 2).

Sexual remarks or gestures were infrequently reported, with 91.5% of participants experiencing no incidents, 6.1% experiencing it once or twice, and smaller percentages experiencing it more frequently.

Bullying victimization category (n=295).

| Questions | No Incidence in the Last two Months | Once or Twice | 2-3 Times per Month | Once per Week | Several Times per Week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| f (%) | f (%) | f (%) | f (%) | f (%) | |

| “I was called mean names, was made fun of, or teased in a hurtful way.” | 162 (54.9) | 93 (31.5) | 12 (4.1) | 4 (1.4) | 24 (8.1) |

| “Other students left me out of things on purpose, excluded me from their group of friends, or completely ignored me.” | 222 (75.3) | 55 (18.6) | 8 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (3.4) |

| “I was hit, kicked, pushed, shoved around, or locked indoors.” | 283 (95.9) | 9 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.0) |

| “Other students told lies or spread rumors about me and tried to make others dislike me.” | 188 (63.7) | 91 (30.8) | 7 (2.4) | 1 (0.3) | 8 (2.7) |

| “I had money or things taken away from me or damaged.” | 252 (85.4) | 9 (3.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| “I was threatened or forced to do things I didn’t want to do.” | 284 (96.3) | 9 (3.1) | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| “I was bullied with mean names or comments about my race or color.” | 255 (86.4) | 29 (9.8) | 3 (1.0) | 2 (0.7) | 6 (2.0) |

| “I was bullied with mean names, comments, or gestures with a sexual meaning.” | 270 (91.5) | 18 (6.1) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.7) | 4 (1.4) |

| “I was bullied with cruel messages or hurtful photographs using a cellphone or Internet.” | 274 (92.9) | 17 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (1.4) |

| “I was bullied in other forms that weren’t mentioned..” | 264 (89.5) | 25 (8.5) | 3 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.7) |

Cyberbullying was also low, with 92.9% experiencing no incidents, 5.8% once or twice, and 1.4% several times per week. Other unspecified forms of bullying were reported by 8.5% once or twice, while 89.5% reported no incidents (Table 2).

3.3. Description of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

Table 3 summarizes the emotional and behavioral characteristics of participants based on SDQ scoring categories. The data showed that most participants exhibited emotional symptoms within the normal range (76.3%), with smaller proportions classified as borderline (10.8%) and abnormal (12.9%). Similarly, the majority of participants demonstrated conduct problems within normal parameters (78.0%), while 12.9% were classified as borderline and 9.2% as abnormal.

For hyperactivity/inattention, 88.8% of participants fell within the normal range, with 8.8% categorized as borderline and only 2.4% as abnormal. Peer relationship problems showed a somewhat different pattern, with 66.4% of participants scoring in the normal range but a notably higher percentage (27.5%) in the borderline category and only 6.1% in the abnormal range. Prosocial behavior was predominantly normal (81.4%), with 10.5% of participants exhibiting borderline scores and 8.1% classified as abnormal.

| Variable | Normal | Borderline | Abnormal |

|---|---|---|---|

| f (%) | f (%) | f (%) | |

| Emotional symptoms | 225 (76.3) | 32 (10.8) | 38 (12.9) |

| Conduct problems | 230 (78.0) | 38 (12.9) | 27 (9.2) |

| Hyperactivity/inattention | 262 (88.8) | 26 (8.8) | 7 (2.4) |

| Peer relationship problems | 196 (66.4) | 81 (27.5) | 18 (6.1) |

| Pro-social behavior | 240 (81.4) | 31 (10.5) | 24 (8.1) |

| Total difficulties score | 219 (74.2) | 47 (15.9) | 29 (9.8) |

The total difficulties score, which provides an overall assessment of emotional and behavioral functioning, indicated that 74.2% of participants were within normal parameters, 15.9% showed borderline difficulties, and 9.8% demonstrated abnormal levels of difficulty.

3.4. Association among Variables

Table 4 presents associations between demographic characteristics, emotional and behavioral disorders, and bullying victimization using independent t-tests and chi-square tests. Variables with p < 0.25 were included in a logistic regression model to test for independence with bullying victimization. These included gender (p = 0.066), with a higher proportion of males as victims, and parents’ marital status (p = 0.068), indicating higher victimization among adolescents from divorced families.

Emotional symptoms (p = 0.030) and conduct problems (p = 0.001) were significantly associated with victimization, with victims exhibiting higher rates of abnormal emotional and conduct scores. Hyperactivity/inattention (p = 0.161) and peer relationship problems (p = 0.248) approached significance and were included in the regression model. The total difficulties score (p = 0.016) was also significantly associated with victimization, as victims had higher scores (Table 4).

| Variable | Category | Bullying Victimization | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Victim (n=232) | Victim (n=63) | |||

| Age (Mean ± SD)a | - | 16.29 ± 0.95 | 16.22 ± 0.88 | 0.576 |

| Genderb | Female | 123 (41.7%) | 25 (8.5%) | 0.066* |

| Male | 109 (36.9%) | 38 (12.9%) | ||

| Class levelb | 10 | 84 (28.5%) | 24 (8.1%) | 0.791 |

| 11 | 60 (20.3%) | 18 (6.1%) | ||

| 12 | 88 (29.8%) | 21 (7.1%) | ||

| Parents marital statusb | Married | 211 (71.5%) | 52 (17.6%) | 0.068* |

| Divorced | 21 (7.1%) | 11 (3.7%) | ||

| Residential statusb | With parents | 207 (70.2%) | 52 (17.6%) | 0.297 |

| Living alone | 9 (3.1%) | 5 (1.7%) | ||

| Living with another family | 16 (5.4%) | 6 (2.0%) | ||

| Paternal educationb | Elementary school | 28 (9.5%) | 10 (3.4%) | 0.846 |

| Junior high school | 30 (10.2%) | 9 (3.1%) | ||

| Senior high school | 120 (40.7%) | 30 (10.2%) | ||

| College | 54 (18.3%) | 14 (4.7%) | ||

| Maternal educationb | Elementary school | 40 (13.6%) | 9 (3.1%) | 0.257 |

| Junior high school | 35 (11.9%) | 16 (5.4%) | ||

| Senior high school | 115 (39.0%) | 26 (8.8%) | ||

| College | 42 (14.2%) | 12 (4.1%) | ||

| Paternal occupationb | Civil servant | 37 (12.5%) | 7 (2.4%) | 0.574 |

| State employee | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Private employee | 38 (12.9%) | 16 (5.4%) | ||

| Self-employed | 57 (19.3%) | 17 (5.8%) | ||

| Retiring | 8 (2.7%) | 1 (0.3%) | ||

| Unemployment | 5 (1.7%) | 2 (0.7%) | ||

| Outsourcing | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.3%) | ||

| Others | 85 (28.8%) | 19 (6.4%) | ||

| Maternal occupationb | Civil servant | 27 (9.2%) | 9 (3.1%) | 0.264 |

| Private employee | 9 (3.1%) | 4 (1.4%) | ||

| Self-employed | 17 (5.8%) | 9 (3.1%) | ||

| Retiring | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Unemployment | 107 (36.3%) | 20 (6.8%) | ||

| Others | 71 (24.1%) | 21 (7.1%) | ||

| Emotional symptomsb | Normal | 184 (62.4%) | 41 (13.9%) | 0.030* |

| Borderline | 24 (8.1%) | 8 (2.7%) | ||

| Abnormal | 24 (8.1%) | 14 (4.7%) | ||

| Conduct problemsb | Normal | 190 (64.4%) | 40 (13.6%) | 0.001* |

| Borderline | 28 (9.5%) | 10 (3.4%) | ||

| Abnormal | 14 (4.7%) | 13 (4.4%) | ||

| Hyperactivity/inattentionb | Normal | 210 (71.2%) | 52 (17.6%) | 0.161* |

| Borderline | 18 (6.1%) | 8 (2.7%) | ||

| Abnormal | 4 (1.4%) | 3 (1.0%) | ||

| Peer relationship problemsb | Normal | 159 (53.9%) | 37 (12.5%) | 0.248* |

| Borderline | 61 (20.7%) | 20 (6.8%) | ||

| Abnormal | 12 (4.1%) | 6 (2.0%) | ||

| Pro-social behaviorb | Normal | 190 (64.4%) | 50 (16.9%) | 0.487 |

| Borderline | 22 (7.5%) | 9 (3.1%) | ||

| Abnormal | 20 (6.8%) | 4 (1.4%) | ||

| Total difficulties scoreb | Normal | 179 (60.7%) | 40 (13.6%) | 0.016* |

| Borderline | 36 (12.2%) | 11 (3.7%) | ||

| Abnormal | 17 (5.8%) | 12 (4.1%) | ||

| Variable | Category | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female (ref.) | 1 | - | - |

| Male | 0.438 | 0.223-0.860 | 0.016* | |

| Parents marital status | Married (ref.) | 1 | - | - |

| Divorced | 0.445 | 0.184-1.072 | 0.071 | |

| Emotional symptoms | Normal (ref.) | 1 | - | - |

| Borderline | 0.282 | 0.086-0.293 | 0.036* | |

| Abnormal | 0.538 | 0.161-1.800 | 0.315 | |

| Conduct problems | Normal (ref.) | 1 | - | - |

| Borderline | 0.241 | 0.83-0.700 | 0.009* | |

| Abnormal | 0.441 | 0.137-1.423 | 0.171 | |

| Hyperactivity/inattention | Normal (ref.) | 1 | - | - |

| Borderline | 0.273 | 0.044-1.687 | 0.163 | |

| Abnormal | 0.274 | 0.040-1.877 | 0.187 | |

| Peer relationship problems | Normal (ref.) | 1 | - | - |

| Borderline | 0.673 | 0.188-2.402 | 0.542 | |

| Abnormal | 0.825 | 0.237-2.870 | 0.762 | |

| Total difficulties score | Normal (ref.) | 1 | - | - |

| Borderline | 1.938 | 0.400-9.392 | 0.411 | |

| Abnormal | 1.404 | 0.392-5.024 | 0.602 |

3.5. Factors associated with Bullying Victimization

Logistic regression analysis results in Table 5 show key factors associated with bullying victimization. Gender was significantly associated, with males having lower odds of victimization than females (OR = 0.438, 95% CI = 0.223–0.860, p = 0.016). Parental marital status approached significance, with adolescents from divorced families having lower odds of victimization compared to those from married families (OR = 0.445, 95% CI = 0.184–1.072, p = 0.071).

Borderline levels of emotional symptoms were significantly linked to lower odds of victimization (OR = 0.282, 95% CI = 0.086–0.293, p = 0.036), and borderline conduct problems were similarly associated with reduced victimization odds (OR = 0.241, 95% CI = 0.083–0.700, p = 0.009). However, abnormal levels of emotional symptoms and conduct problems did not show significant associations (Table 5).

Hyperactivity/inattention was borderline significant, with reduced odds of victimization in both borderline and abnormal levels (borderline: OR = 0.273, 95% CI = 0.044–1.687, p = 0.163; abnormal: OR = 0.274, 95% CI = 0.040–1.877, p = 0.187) (Table 5). Peer relationship problems and total difficulties scores were not significantly associated with bullying victimization. Overall, gender, emotional symptoms, and conduct problems, particularly in the borderline range, emerged as significant factors associated with bullying victimization in this sample.

4. DISCUSSION

The study findings can be interpreted through the integrated theoretical framework combining developmental psychopathology and social-ecological models. Within this framework, the predominance of verbal bullying, social exclusion, and rumor-spreading reflects a complex interplay between individual vulnerabilities and contextual factors operating across multiple levels. The developmental psychopathology perspective explains how these victimization experiences may influence and be influenced by individual psychological trajectories, creating potentially recursive vulnerability patterns. The social-ecological framework places these dynamics within Indonesia’s distinctive sociocultural context, where collectivist values, educational structures, and gender socialization practices function as moderating mechanisms.

The gender-differentiated victimization patterns identified in this study, with males demonstrating significantly lower victimization, align with theoretical propositions regarding the cultural specificity of risk trajectories. Similarly, the counterintuitive inverse relationship between borderline psychological symptoms and victimization risk underscores the symptom-driven model’s cultural contingency, suggesting that within Indonesia’s unique social parameters, moderate symptomatology may function through distinct pathways not adequately captured in Western-derived theoretical models. This integrated theoretical lens enhances the interpretation of the empirical findings while highlighting the necessity of culturally contextualized approaches to understanding victimization dynamics within Indonesian adolescent populations.

The predominance of verbal bullying among participants aligns with established evidence documenting verbal aggression as the most pervasive form of peer victimization. Previous research consistently identifies verbal abuse encompassing name-calling, mocking, and insulting as the most prevalent bullying typology among school-aged populations [35]. This phenomenon can be contextualized within a comprehensive victimization framework that categorizes peer aggression into four distinct domains: verbal victimization, physical victimization, social manipulation, and property-directed attacks [36]. The implications of these findings extend beyond prevalence documentation to encompass serious psychological consequences, including elevated risk for depression, anxiety, and disrupted social cognitive processing [37], necessitating the implementation of comprehensive, gender-responsive intervention frameworks that address both digital and interpersonal manifestations of verbal aggression within Indonesia’s educational context [38].

Bullying among adolescents remains a pervasive issue, with various forms emerging from different contexts. Similar to the present study, previous research has highlighted verbal bullying, social exclusion, and rumor-spreading as the most commonly reported types of bullying among adolescents. For example, Jilani et al. found that verbal bullying was the predominant form among adolescents, consistent with global data that frames verbal aggression as a traditional mode of victimization in this age group [39]. Douvlos also noted that verbal aggression, social exclusion, and rumor-spreading behaviors begin as early as preschool, emphasizing the early onset and persistence of these behaviors [40]. Han et al. further corroborated this trend by identifying high frequencies of verbal and relational bullying among adolescents in diverse bullying contexts [41].

The impact of bullying behaviors extends beyond the individual victims to affect broader social environments, as repeated victimization can lead to serious emotional and social consequences. Shiba et al. discussed how continued exposure to bullying often results in severe emotional distress and social withdrawal among adolescents [42]. Tarafa et al.’s research similarly reported that approximately 30.4% of adolescents in their study experienced bullying, suggesting a global prevalence of the issue with far-reaching psychosocial outcomes [18]. These findings reinforce the urgent need for effective intervention strategies that address the widespread and universal nature of bullying.

This study’s findings also reveal significant gender differences in bullying victimization. Consistent with prior research, males in this study were less likely to be victims compared to females, who are often more involved in relational bullying, such as social exclusion and rumor-spreading. Additionally, previous research found that underweight girls were particularly vulnerable to social exclusion and rumor-spreading, highlighting how physical appearance can intersect with gender to influence bullying dynamics [43]. Another study also observed that verbal and social bullying were prevalent among middle school students, especially those with specific learning disabilities, suggesting that particular vulnerabilities may exacerbate bullying experiences [44].

Several mechanisms may explain the gender differences in bullying victimization. Indonesia’s patriarchal social structure creates distinctive gender socialization patterns wherein males receive cultural reinforcement for dominant behaviors while females encounter greater expectations for compliance and conflict avoidance [5], potentially increasing female vulnerability within educational hierarchies. Moreover, Indonesia’s educational infrastructure, characterized by gender-segregated activities and differential behavioral expectations for males and females, may create gender-specific risk environments that disproportionately expose females to victimization. These mechanisms highlight the complex interplay between sociocultural factors and gender-differentiated victimization risk, underscoring the need for gender-responsive intervention strategies that address these underlying structural and social determinants.

Family dynamics, including parental marital status, significantly influence bullying victimization. In alignment with this study, previous research suggests that adolescents from divorced or separated families are at heightened risk of experiencing bullying victimization. Sanayeh et al. found that parental divorce could lead to feelings of shame and stigmatization, which affect adolescents’ self-esteem and social interactions, increasing their vulnerability to being bullied [45]. Similarly, Hu et al. reported that Left-Behind Children (LBC) with divorced parents had higher rates of bullying victimization compared to those from intact families, underscoring the protective role of family stability [46]. Furthermore, studies by Tran et al. and Obeïd et al. reveal that parental separation is associated with increased rates of mental health issues, such as anxiety and depression, which are often correlated with a higher likelihood of bullying victimization [47, 48]. The emotional upheaval from family disruptions may amplify feelings of isolation and inadequacy, creating a cycle of victimization in school settings.

Regarding the impact of parental marital status on bullying victimization, this marginal association should be interpreted as a preliminary indicator requiring validation through subsequent investigations with enhanced statistical power. Future research would benefit from larger, more demographically diverse samples that facilitate robust subgroup analyses while controlling for potential confounding variables. Longitudinal designs would further strengthen inferential capacity by clarifying temporal relationships between family structure transitions and victimization trajectories. The current findings should thus be positioned as hypothesis-generating rather than conclusive, contributing to an evolving empirical framework examining family dynamics and peer victimization within Indonesia’s sociocultural context.

This study further underscores the strong link between bullying victimization and emotional and behavioral issues among adolescents. Consistent with previous research, our findings reveal that adolescents who experience bullying are more susceptible to mental health problems, including anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem. A previous study found that adolescents who identified as victims faced increased emotional distress and social withdrawal, pointing to the profound emotional impacts of victimization [49]. Another previous study also indicated that children with pre-existing emotional or behavioral problems are more likely to become targets and may face elevated risks of self-harm following victimization [50].

Bullying can exacerbate existing emotional challenges, creating a cycle of victimization and psychological distress. Schütz et al. reported that adolescents with emotional-social developmental challenges exhibited higher rates of bullying and related emotional issues [51]. Franzen et al. added that adolescents with poor emotional regulation skills may also become targets due to their intense reactions, which can attract further victimization [52]. This interplay between emotional dysregulation and bullying highlights the need for interventions that address emotional regulation and coping skills among at-risk youth.

The mental health effects of bullying can extend beyond immediate distress to have long-term consequences. Hamstra et al. found that bullying victimization increased the likelihood of developing behavioral and psychological issues in later life, particularly among those who experienced maltreatment at home [53]. Fu et al. also observed that early experiences of bullying could lead to neurobiological changes associated with mental health problems in adulthood, highlighting the potential lasting impact of peer victimization [54]. These findings emphasize the critical need for early intervention to prevent enduring psychological harm among adolescents.

The observed inverse relationship between borderline emotional symptoms, conduct problems, and reduced odds of victimization warrants careful interpretation within Indonesia’s unique sociocultural context. This seemingly counterintuitive finding wherein adolescents with borderline symptomatology demonstrated lower victimization odds contrasts with established literature documenting positive associations between psychological difficulties and victimization vulnerability [24, 26]. Several explanatory mechanisms merit consideration. First, the cross-sectional design precludes the determination of temporal sequencing, potentially obscuring bidirectional relationships documented in longitudinal investigations [23]. Second, within Indonesian collectivist cultural frameworks, borderline symptom manifestation may function as a protective mechanism through specific behavioral adaptations. Adolescents exhibiting mild conduct problems may develop enhanced vigilance or strategic social positioning that mitigates victimization risk [12]. Similarly, those with borderline emotional symptoms may employ selective social withdrawal as a preemptive strategy, reducing exposure to high-risk peer interactions.

Furthermore, measurement considerations must be acknowledged, as the SDQ’s validated Indonesian adaptation may capture culturally specific symptom expressions that function differently within peer dynamics than those observed in Western contexts. Notably, this protective association was observed exclusively for borderline symptomatology, while abnormal levels of emotional symptoms and conduct problems demonstrated non-significant relationships with victimization odds. This non-linear pattern suggests that emotional and behavioral symptoms may operate through complex, threshold-dependent mechanisms within Indonesian adolescent social ecosystems, wherein moderate symptom levels may confer strategic advantages while severe manifestations potentially increase vulnerability through more extreme social impairments.

5. LIMITATION

This study has several limitations that are specific to the context in which it was conducted. First, the study was carried out within a single high school in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other regions within Indonesia or to other cultural contexts. Therefore, the findings may not fully capture the experiences of adolescents in different parts of Indonesia, especially in urban or densely populated areas where social interactions and peer dynamics can vary significantly. Moreover, the analytical framework did not incorporate critical school-level ecological factors that demonstrably influence bullying dynamics. Specifically, the absence of data regarding institutional anti-bullying policies, implementation fidelity, teacher awareness, intervention competencies, and supervisory practices and enforcement mechanisms represents a significant limitation.

While the study focused on demographic factors such as parental marital status and parental education, it did not include other potentially influential contextual factors, such as school environment, teacher-student relationships, or peer group characteristics, which can play a significant role in bullying dynamics. The school culture, including policies on bullying and the availability of support systems for students, may affect the prevalence and types of bullying behaviors observed. Understanding these contextual influences would provide a more comprehensive view of bullying victimization among adolescents.

6. IMPLICATION

Despite these limitations, the study provides important implications for practice and policy. Schools can implement programs that promote empathy, social skills, and peer support to reduce verbal and relational bullying. The empirical findings necessitate the implementation of structured communicative competence programs specifically addressing verbal aggression through explicit instruction in respectful communication practices, cognitive reframing techniques, and comprehensive bystander intervention training. Furthermore, the documented gender differentials in victimization risk require gender-responsive intervention components, including gender-specific support groups, curriculum addressing gender role constraints, and targeted empowerment strategies for female students who demonstrated higher victimization vulnerability. Additionally, the association between bullying victimization and parental marital status highlights the need for support programs for adolescents from divorced or separated families. Counseling and support services could help these adolescents develop coping strategies to mitigate the emotional effects of family instability and reduce their vulnerability to bullying. Furthermore, early identification and support for adolescents struggling with emotional and behavioral issues could help reduce their risk of becoming bullying victims and improve their overall well-being. Finally, policymakers should consider implementing comprehensive anti-bullying policies that address both direct and indirect forms of bullying, providing a structured framework for prevention and intervention. Collaborative efforts between schools, families, and mental health professionals are essential to create a supportive environment that reduces bullying and promotes mental health among adolescents.

CONCLUSION

This investigation provides valuable insights into bullying victimization patterns among adolescents in Central Kalimantan, Indonesia, documenting the prevalence of various bullying typologies and identifying significant associations with gender, emotional symptoms, and conduct problems. A comprehensive assessment framework incorporating institutional policy characteristics, implementation parameters, teacher efficacy measures, and perceived safety indices would enhance understanding of contextual factors influencing bullying dynamics. Future studies should prioritize the identification of culturally specific protective factors that potentially moderate victimization vulnerability. The finding regarding borderline emotional symptoms suggests complex protective mechanisms may operate within Indonesia's unique educational context. Longitudinal research designs with multiple assessment points would facilitate the examination of bidirectional relationships between psychological functioning, social position, and victimization experiences, thereby elucidating developmental pathways and potential intervention targets.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: I.W.A.: Study conception and design; I.W.A. and I.M.M.Y.S.: Data collection; I.W.A. and I.M.M.Y.S.: Data Analysis or Interpretation; I.W.A.: Methodology; F.F., D.K., A.B.W., R.W.E., and R.A.A.: Investigation; I.W.A., F.F., D.K., A.B.W., R.W.E., R.A.A., and I.M.M.Y.S.: Draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| SLOW | = Sleep Loss due to Worry |

| SDQ | = Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire |

| OBVQ-R | = Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Committee at the Faculty of Health Sciences, Universitas Muhammadiyah Malang, in accordance with WHO 2011 standards and CIOMS 2016 guidelines (Approval No. E.4.d/079/KEPK/FIKES-UMM/X/2024).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all adult participants, as well as from the parents or legal guardians of minors.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article will be available from the corresponding author [IW.A] upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.