All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Social Support, Spiritual Well-being, and Quality of Life Among Muslim Converts in Indonesia

Abstract

Introduction

The present study seeks to examine the mediating role of spiritual well-being in the relationship between social support and quality of life (QoL) among Muslim converts, known as "mualaf," in Indonesia.

Methods

Drawing upon a sample of 119 mualaf (comprising 41 males and 78 females) from diverse regions across Indonesia, the study utilised validated instruments to measure social support, spiritual well-being, and QoL. The Sobel test was employed to evaluate the mediating effect of spiritual well-being.

Results

The results unveiled three pivotal findings: (1) social support exerts both a direct and indirect influence on QoL, mediated by spiritual well-being; (2) a significant gender disparity is evident, with female mualaf manifesting higher levels of spiritual well-being than their male counterparts; and (3) mualaf who have recently embraced Islam (less than two years) exhibit higher spiritual well-being scores compared to those who have embraced Islam for a longer duration (more than two years).

Discussion

The results underscore the role of spiritual well-being as a mediator of the relationship between social support and QoL, as well as the role of social support in promoting spiritual well-being among mualaf. The implications of these findings include the need to build social support for converts, particularly during critical periods for the development of their religious identity and psychospiritual stability.

Conclusion

In summary, this study offers robust evidence that spiritual well-being serves as a pivotal factor in the intricate relationship between social support and QoL among mualaf.

1. INTRODUCTION

Indonesia is a multicultural nation consisting of diverse ethnic groups, cultures, and religions. The country officially recognizes six religions: Islam, Christianity, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. The majority of Indonesia's population is Muslim, and the statistics show a steady increase in the Muslim population over the years. In 1990, Muslims accounted for 87.6% of the population; this increased to 88.2% in 2000 and reached 91.03% in 2016 [1]. These statistics reflect the overall percentage dynamics but do not provide comprehensive information on the conversion rates of Muslims.

The terms “convert” and “revert” are often used interchangeably to describe someone who changes their religious beliefs. In this article, we use the term “convert” in a manner that both Muslims and non-Muslims widely understand. While “revert” might be more appropriate among Muslims who understand its specific usage, “convert” ensures broader accessibility of this article to all groups.

Religious conversion is significant because of the central role that religious beliefs play in an individual's life. It encompasses a change of belief along with alterations in behavior and social relationships. Religious conversion can lead to both gradual and sudden changes in attitudes and behaviors. As Tumanggor notes, changes in religious affiliation can occur either gradually, which strengthens an individual's readiness for change, or suddenly, which can trigger profound physical, psychological, and social impacts [2]. This process begins with a declaration to embrace a new faith.

The declaration of religious conversion is influenced by a broader context, shaped by events before and after the decision. Familial, social, and internal factors intricately influence this process [3, 4]. Internal struggles often involve grappling with the veracity of different religious tenets, necessitating decisions aligned with evolving beliefs. Familial challenges can manifest as rejections, including prohibitions, threats, physical violence, expulsion, and ostracism [5, 6]. Social repercussions may extend to the professional sphere, where converts can face intimidation and, in some cases, job termination.

The multitude of challenges faced by converts underscores the arduous nature of religious conversion. This turbulent spiritual journey often brings internal turmoil during the search for truth and the decision-making process. Tensions rise when they encounter pressure from their immediate environment, particularly from family and society. In this context, social support, especially from family, plays a crucial role in bolstering the psychological and spiritual resilience of converts. Research indicates that strong family support can enhance emotional well-being, self-confidence, and a sense of belonging in a new community [7, 8]. Conversely, when converts face rejection from their family and social networks, they bear a significantly heavier psychological burden. Often, they are compelled to leave their homes, lose financial support, and even endure verbal and emotional abuse from their family members [9, 10]. Although they may outwardly appear happy to have found a new faith, the sacrifices they must endure, such as losing property, losing homes, and severing family ties, illustrate the complexity and profundity of the spiritual and social experience they are undergoing.

1.1. Quality of Life

The aforementioned circumstances have a significant impact on the QoL of individuals who undergo religious conversion. The concept of QoL is multifaceted and subject to various interpretations, influenced by factors such as food, social support, education, health, and religion [11, 12]. Despite diverse perspectives, a universally agreed-upon definition of QoL remains elusive [13]. Some scholars emphasize its subjective nature, highlighting individuals' perceptions of essential life aspects [14]. Achieving one's desired position is often considered indicative of a favorable QoL.

Defar et al. [15], explained that QoL is an individual's capacity to optimize their physical, psychological, social, and occupational functioning. In contrast, the World Health Organization (WHO) adopts a broader perspective, defining QoL as an individual’s perception of their life within the context of their values, culture, and comparisons with previously established goals and standards [14, 16]. Within this framework, the WHO identifies six key components: physical health, psychological well-being, independence, social interaction, environmental interaction, and spiritual well-being. Alternatively, some researchers propose a consolidated model, categorizing QoL into four components: physical health, psychological well-being, social interaction, and environmental interaction [17, 18].

Murphy et al. [19], argues that several interconnected factors, including independence, physical and mental health, socio-economic status, living environment, culture, and psychological and spiritual well-being, shape QoL. Independence refers to the ability to make decisions and exercise self-control, while physical and mental health refer to the capacity to perform daily activities effectively. Socio-economic factors encompass income, stable employment, and property ownership. Environmental aspects involve feelings of safety and comfort within one’s community. Cultural factors are tied to the habits and traditions of the surrounding society, and psychological and spiritual well-being reflect an individual’s ability to find meaning in their experiences and address transcendent needs.

1.2. Spiritual Well-being (SWB)

The human condition is characterised by an intrinsic need for spiritual connection, a concept referred to as “spiritual health” by Heng et al. [20]. This not only influences other human needs but also serves as a guiding force that shapes and directs them. The fulfilment of spiritual needs has been shown to significantly contribute to the attainment of individual spiritual well-being.

Mathad et al. [21], describe spiritual well-being as a multidimensional construct that reflects a state of spiritual health. Scholars define it as a positive alignment with life, encompassing connections to a divine entity, oneself, one’s community, and the broader environment [22]. These connections are expressed across four domains: transcendental, personal, communal, and environmental.

The transcendental domain, as outlined by Fisher et al. [22], pertains to an individual's relationship with a realm beyond human limitations, encompassing ultimate meaning, cosmic influence, and a transcendent reality. The personal domain involves an individual's capacity for self-governance in discovering meaning, value, and purpose in life. The communal domain assesses the degree of interaction within the community, particularly in relation to moral, cultural, and religious dimensions. Lastly, the environmental domain focuses on how individuals engage with and contribute to the preservation of their physical and social environment.

Contrary to a narrow focus on religious rituals, spiritual well-being encompasses broader life perspectives, cherished values, and belief systems [23]. Its ramifications are manifold, including augmented problem-solving capabilities. Graham et al. [24] assert that individuals attributing greater significance to spirituality allocate more attention to it, thereby empowering themselves to navigate and surmount various challenges. A spiritually flourishing individual demonstrates the ability to transform adverse life circumstances into opportunities for positive spiritual growth and evolution.

1.3. Social Support

Social support, as defined by King et al. [25], refers to the provision of information, feedback, and additional resources from individuals within one’s network, indicative of care, affection, esteem, and reciprocal communication. Li et al. [26], emphasise that social support is a condition available to an individual through social connections to other individuals, groups, and the wider community. This highlights the dual nature of social support, encompassing both external (social) and internal (individual) components.

The theoretical framework underpinning the understanding of social support revolves around two fundamental dimensions: structural and functional. The structural dimension examines the size and frequency of social interactions. In contrast, the functional dimension delves into both emotional (e.g., empathy, affection) and practical (e.g., financial assistance, educational resources) aspects of support [27]. Sources of social support include family, friends, and significant others, offering various forms of support, such as emotional, instrumental, evaluative, and informational support.

A substantial body of empirical evidence consistently indicates a positive correlation between social support and QoL [28]. Enhanced social support typically correlates with improved QoL. However, the exact nature of this relationship and its universal applicability across diverse individual circumstances remain subjects of scholarly debate. Meanwhile, Alorania and Alradaydeh [29], found a positive correlation between social support and spiritual well-being. The higher the social support received, the higher the level of spiritual well-being.

Conversely, research findings on the association between spiritual well-being and QoL present conflicting outcomes. While some studies report no direct link [30, 31], others demonstrate a significant positive relationship [20]. This disparity in results underscores a critical research gap in understanding the complex interplay between social support, spiritual well-being, and QoL. In addition, there are differences in findings regarding QoL and spiritual well-being in men and women. On one side, scholars found that men have a better QoL than women [32], and women have higher spiritual well-being than men [33]. On the other side, scholars argue that there was a paradox where women were both more stressed and had more QoL [34], and there was no difference in spiritual well-being based on gender [20].

Previous studies on Muslim converts in Indonesia have been conducted by several researchers, including Tahir [35], Fansuri [36], and Abidin [37]. Persuasive communication strategies in fostering converts, highlighting the importance of an effective communicative approach in the process of religious mentoring [35]. Fansuri focuses on the transformation of religious identity and the socio-cultural challenges faced by converts in urban society [36]. Meanwhile, Abidin examined the role of Chinese Muslim organizations in assisting the process of fostering converts from ethnic Chinese backgrounds, emphasizing the cultural and communitarian aspects [37]. Although all three make important contributions to understanding the social and cultural realities of converts, none have specifically examined the relationship between social support, spiritual well-being, and quality of life in a comprehensive analytical framework. Therefore, this study fills this gap by offering an integrative approach that examines the mediating role of spiritual well-being in the relationship between social support and the quality of life of converts.

Following a declaration of religious conversion, particularly among Muslim converts, individuals undergo significant shifts in beliefs and social relationships. These changes inevitably influence their overall well-being and, more specifically, their QoL. To address the inconsistencies in existing research regarding the correlation between social support, spiritual well-being, and QoL, this study aims to explore the potential mediating role of spiritual well-being in the relationship between social support and QoL among Muslim converts. We also aim to examine the differences in QoL and spiritual well-being between men and women. Thus, this study hypothesizes that spiritual well-being could mediate the relationship between social support and QoL. Furthermore, we hypothesize that there would be a difference between men’s scores and women’s scores on QoL and spiritual well-being.

2. METHOD

This study utilised a quantitative research methodology to examine the population, employing statistical techniques for data analysis. This descriptive research investigates spiritual well-being as a mediator for the relationship between social support and QoL among Muslim converts. Initially, the research population encompassed all Muslim converts in Indonesia, spanning 38 provinces. However, the respondents who completed the online questionnaire were predominantly from these five provinces: Central Java, East Java, West Java, Jakarta, and West Kalimantan. We hypothesize that the majority of Muslim converts in Indonesia reside in the five provinces listed below.

Contrary to initial expectations that data collection would be straightforward due to the large number of converts to Islam in Indonesia, the process proved to be challenging. Data collection commenced through online questionnaires distributed via a Google Form link shared on social media platforms and collected directly in the field. Based on the data we gathered, the majority of respondents originated from five provinces, namely Central Java, Yogyakarta, West Java, East Java, and Jakarta. This study was conducted with the utmost diligence and commitment, ensuring a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the subject matter.

2.1. Participants

This study engaged Muslim converts who had transitioned from their previous religious beliefs to Islam. Through a randomised selection process, two research assistants recruited 119 participants, comprising 41 males and 78 females. Participation was predicated upon obtaining written informed consent from each participant, a process undertaken with due diligence. Ethical clearance was granted by the Research Institute of Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta. The sample demonstrated diverse religious backgrounds, with prior affiliations to Catholicism, Christianity, Hinduism, Buddhism, and other faiths. The duration of conversion to Islam reflected the diversity within the Muslim convert community. The ethics approval number is 4558A/B.2/KEPK-FKUMS/XI/2023.

2.2. Instruments

To ensure the participation of study respondents, the researchers employed a random selection process. In appreciation, a thoughtful souvenir was presented to each participant as a token of gratitude. Ethical approval was granted by the Research Institute of Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, affirming the study's adherence to established ethical guidelines.

The Social Support Scale, developed by Cohen et al. [38], measures the functional dimensions of social support. This instrument is a condensed version of the original Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL), consisting of 40 items [39]. The scale consists of three subscales: appraisal support, belonging support, and tangible support. Each subscale comprises four items, measured on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 'Strongly Disagree' to 'Strongly Agree.' For the purposes of this study, the researchers modified the scale by adding an additional point, thereby converting it into a 5-point scale: 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, and 5 = Strongly Agree. The content validity of the social support scale was assessed using the Aiken [40], formula with a minimum score of 0.78 and a maximum score of 0.80, indicating its validation. The Social Support Scale demonstrated good internal consistency, as evidenced by a Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.80 for the overall scale.

The spiritual well-being Questionnaire, consisting of 16 items, was developed by Ellison [41]. Respondents indicated their responses on a five-point Likert scale: 1= Strongly Disagree, 2= Disagree, 3= Neutral, 4= Agree, and 5= Strongly Agree. Content validity was assessed through expert judgment by nine experts, ensuring clarity and representation of aspects related to spiritual well-being. The Aiken [40], formula was used to determine the scale’s validity, with scores ranging from 0.81 to 0.94. Based on the Aiken formula, the scale is valid. Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the questionnaire was 0.89, indicating good internal consistency for the overall scale.

The QoL scale utilised in this study is a modification of the WHOQOL-BREF instrument, comprising 17 statement items. Utilising a Likert scale for each domain, participants responded on a five-point scale: 1= Strongly Disagree, 2= Disagree, 3= Neutral, 4= Agree, and 5= Strongly Agree. Similar to previous instruments, content validity was evaluated by nine experts using the Aiken [40] formula, with validity scores ranging from 0.75 to 0.89, thereby affirming the validity of the QoL scale. The Cronbach's alpha coefficient (0.87) indicated a good internal consistency for the overall scale.

2.3. Procedures

The research unfolded through a series of structured phases. Initially, the target population was identified as Muslim converts residing across diverse regions within Indonesia. A simple random sampling technique was employed to select suitable participants from this population. Simple random sampling was employed in instances where researchers lacked detailed information about potential research respondents. Initial data were obtained from the Indonesian Mualaf Center (MCI) data centre and the BAZNAS Yogyakarta Mualaf Center. However, direct interaction with respondents was not feasible. Consequently, these organisations assisted in distributing the questionnaires (via Google Forms) through whatsapp and facebook groups under their management.

Additionally, the questionnaires were disseminated more broadly on social media platforms, including whatsapp and facebook. Simultaneously, all research instruments, including the QoL scale, the spiritual well-being scale (SWB scale), and the social support scale, underwent rigorous content validity assessments using the Aiken formula to ensure their reliability and appropriateness for the study [40]. Following instrument validation, data collection commenced with the distribution of online questionnaires via a Google Form link shared on social media platforms. Upon completion of data collection, responses were scored and subjected to a comprehensive analysis to extract meaningful insights. This study was conducted with the utmost rigour and commitment, ensuring a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the subject matter.

2.4. Data Analysis

This study utilized various analytical tools to conduct a comprehensive data analysis, including regression analysis, Pearson’s product-moment correlation, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and the independent samples t-test. Regression analysis was employed to explain the variability in dependent variables based on one or more independent variables. Pearson’s product-moment correlation measured the linear relationship between two variables assessed on interval or ratio scales. Additionally, ANOVA was applied to examine differences among the means of more than two groups, while the independent samples t-test was used to compare the means of two unrelated groups. In addition to these, the Sobel Test was also used to assess the presence of a significant correlation mediated by a third variable [42]. The Sobel test is a versatile statistical tool that can be applied in three variations: the Sobel test, the Aroian test, and the Goodman test. Calculating the statistics and p-values for the Sobel test requires considering the results from all three versions. In this study, the Sobel test was employed to examine the potential mediating role of spiritual well-being in the relationship between social support and QoL. The Sobel test provided valuable insights into the dynamic interplay between these constructs by examining the mediating role of spiritual well-being, thereby shedding light on how it influences the relationship between social support and QoL among Muslim converts.

3. RESULTS

The Group Statistics and the results of the Independent Samples t-test are presented in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. The findings indicate no significant differences in QoLs or Social Support between genders. However, a significant difference was observed in the spiritual well-being variable, with women exhibiting higher levels of spiritual well-being than men (p < .05). Additionally, variations in spiritual well-being were evident among converts, depending on the duration of their conversion to Islam (p < .05).

The data description, ANOVA results, and Post Hoc Test findings are presented in Tables 3-5, respectively. These tables reveal a significant relationship between the duration of adherence to Islam and the level of spiritual well-being. Muslim converts who have adhered to Islam for less than two years demonstrate higher levels of spiritual well-being compared to those who have practiced Islam for over two years (effect size: Cohen's d = 0.45, indicating a moderate effect). The findings suggest a negative correlation between prolonged practice of Islam and elevated spiritual well-being. However, no significant differences were identified in QoL or social support based on the duration of adherence to Islam.

| - | Gender | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | Males | 41 | 55.22 | 6.287 | 0.982 |

| Females | 78 | 54.51 | 7.637 | 0.865 | |

| Spiritual well-being | Males | 41 | 59.44 | 8.983 | 1.403 |

| Females | 78 | 63.14 | 7.754 | 0.878 | |

| Social support | Males | 41 | 29.71 | 4.644 | 0.725 |

| Females | 78 | 30.28 | 5.175 | 0.586 |

| - | Levene’s Test for Equality of Variances | t | df | t-test for Equality of Means | 95% Confidence Interval of the Difference | Sample Effect Size Cohen’s d |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | Sig. | Sig. | Mean Differ. | Std. Error Differ. | Lower | Upper | Standardizer | Point Estim. | ||||

| Quality of life | Equal variances assumed | 0.433 | 0.512 | 0.509 | 117 | 0.612 | 0.707 | 1.390 | -2.046 | 3.459 | 7.204 | 0.098 |

| Spiritual well-being | Equal variances assumed | 1.008 | 0.317 | -2.342 | 117 | 0.021 | -3.702 | 1.581 | -6.833 | -0.571 | 8.195 | -0.452 |

| Social support | Equal variances assumed | 1.161 | 0.284 | -0.596 | 117 | 0.552 | -0.575 | 0.964 | -2.485 | 1.335 | 4.999 | -0.115 |

| - | Time Duration | N | Mean | SD | Std. Error | 95% Confidence Interval for Mean | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||||||

| Quality of life | More than 5 years | 25 | 52.00 | 7.948 | 1.590 | 48.72 | 55.28 | 31 | 64 |

| 2-5 years | 26 | 56.62 | 6.747 | 1.323 | 53.89 | 59.34 | 46 | 71 | |

| Less than 2 years | 68 | 55.06 | 6.852 | 0.831 | 53.40 | 56.72 | 32 | 68 | |

| Total | 119 | 54.76 | 7.182 | 0.658 | 53.45 | 56.06 | 31 | 71 | |

| Spiritual well-being | More than 5 years | 25 | 57.48 | 9.288 | 1.858 | 53.65 | 61.31 | 33 | 75 |

| 2-5 years | 26 | 61.46 | 7.295 | 1.431 | 58.51 | 64.41 | 50 | 75 | |

| Less than 2 years | 68 | 63.63 | 7.849 | 0.952 | 61.73 | 65.53 | 36 | 75 | |

| Total | 119 | 61.87 | 8.349 | 0.765 | 60.35 | 63.38 | 33 | 75 | |

| Social Support | More than 5 years | 25 | 28.24 | 4.833 | 0.967 | 26.25 | 30.23 | 19 | 38 |

| 2-5 years | 26 | 30.96 | 4.294 | 0.842 | 29.23 | 32.70 | 22 | 38 | |

| Less than 2 years | 68 | 30.60 | 4.738 | 0.575 | 29.46 | 31.75 | 20 | 40 | |

| Total | 119 | 30.18 | 4.737 | 0.434 | 29.32 | 31.04 | 19 | 40 | |

| - | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | ANOVA Effect Size Cohen’s d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of life | Between groups | 286.014 | 2 | 143.007 | 2.860 | 0.061 | 0.002 |

| Within groups | 5799.919 | 116 | 49.999 | - | - | - | |

| Total | 6085.933 | 118 | - | - | - | - | |

| Spiritual well-being | Between groups | 697.338 | 2 | 348.669 | 5.372 | 0.006 | 0.045 |

| Within groups | 7528.510 | 116 | 64.901 | - | - | - | |

| Total | 8225.849 | 118 | - | - | - | - | |

| Social support | Between groups | 122.132 | 2 | 61.066 | 2.805 | 0.065 | 0.003 |

| Within groups | 2525.801 | 116 | 21.774 | - | - | - | |

| Total | 2647.933 | 118 | - | - | - | - | |

| Multiple Comparison | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable: Spiritual Well-being | ||||||

| (I) Duration | (J) Duration | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. | 95% Confidence Interval | |

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||

| Less than 2 years | 2-5 years | -3.982 | 2.257 | 0.080 | -8.45 | 0.49 |

| More than 5 years | -6.152* | 1.884 | 0.001 | -9.88 | -2.42 | |

| 2-5 years | Less than 2 years | 3.982 | 2.257 | 0.080 | -0.49 | 8.45 |

| More than 5 years | -2.171 | 1.858 | 0.245 | -5.85 | 1.51 | |

| More than 5 years | Less than 2 years | 6.152* | 1.884 | 0.001 | 2.42 | 9.88 |

| 2-5 years | 2.171 | 1.858 | 0.245 | -1.51 | 5.85 | |

| Coefficientsª | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients Beta |

t | Sig. | |

| B | Std. Error | ||||

| Constant | 21.172 | 4.634 | - | 4.568 | 0.000 |

| Social support | 0.273 | 0.118 | 0.189 | 2.311 | 0.023 |

| Spiritual well-being | 0.430 | 0.079 | 0.500 | 5.438 | 0.000 |

| Input | Test | Statistic Test | Std. Error | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | 0.353 | Sobel test | 2.357 | 0.064 | 0.018 |

| b | 0.430 | Aroian test | 2.325 | 0.065 | 0.020 |

| Sa | 0.135 | Goodman test | 2.389 | 0.063 | 0.016 |

| Sb | 0.079 | - | - | - | - |

Correlation model.

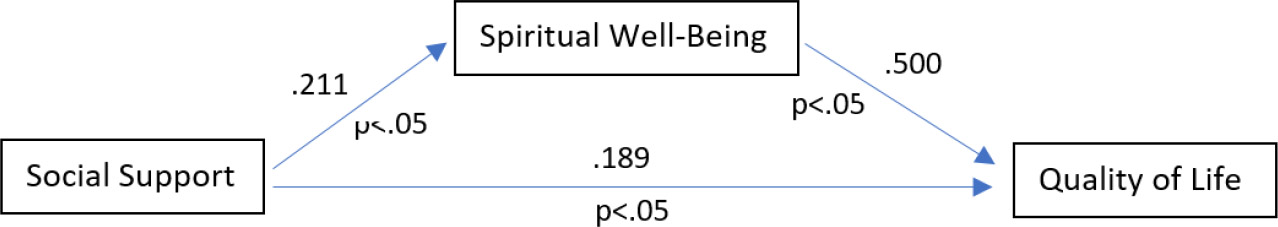

As demonstrated in Table 6, a significant association is observed between social support, spiritual well-being, and QoL, with coefficients of Beta = 0.189, p < 0.05, and Beta = 0.500, p < 0.05, respectively. Furthermore, the results of the product-moment analysis highlight a substantial correlation between social support and spiritual well-being (Beta = .211, p < .05). These findings imply that social support influences QoL, while concurrently impacting QoL through spiritual well-being, which functions as a mediator. Furthermore, spiritual well-being is also found to have a direct relationship with QoL.

The Sobel Test was employed to examine the direct and indirect effects of social support on QoL, with spiritual well-being serving as a mediating variable. The calculations utilized the “Calculation for Sobel Test” method developed by Preacher and Hayes [43], which involved inputting the coefficient scores and standard errors derived from the Regression Analysis and Product-Moment Analysis. Based on Table 7 above, the analysis produced a t-count value of 2.357, exceeding the t-table value of 1.98, with a p-value < .05, indicating a significant mediation effect of spiritual well-being on the relationship between social support and QoL. Additionally, social support demonstrated a direct effect on QoL, albeit with a reduced correlation when the mediation effect was accounted for. The model illustrating these relationships is presented in Fig. (1).

4. DISCUSSION

A perusal of the descriptive table unveils a captivating array of findings. Some variables present significant differences between groups, while others show no discernible variations. A striking disparity is observed in the sphere of spirituality, where female participants exhibit significantly higher levels of well-being compared to their male counterparts. This observation is consistent with an expanding body of research that highlights persistent gender differences in spiritual experiences, with women consistently demonstrating greater spiritual inclinations than men [44].

A considerable body of research has been devoted to examining the underlying mechanisms that contribute to gender disparities in spirituality. Stark [45], suggests that women's inherent predisposition to engage with religious institutions, participate in regular prayer, and exhibit greater awareness of religion's significance in their lives plays a pivotal role in this phenomenon. Moreover, women display a heightened tendency to believe in an afterlife, further distinguishing them from their male counterparts. Empirical support for this observation is provided by Cloniger et al. [46], who report an 18% higher self-transcendence score among women in their study of 1,388 individuals.

Miller and Stark [47], provide an intriguing perspective on this spiritual disparity, drawing upon the “risk preference theory.” The proposed theory suggests that irreligiosity should be regarded as a disadvantageous state. Consequently, it is hypothesised that individuals may experience retribution for this perceived transgression. Furthermore, based on documented evidence indicating that women exhibit a greater aversion to risk compared to men, it is predicted that women are more likely to conform to religious principles. The theory further proposes a divergence in risk tolerance between genders, suggesting that men exhibit a greater propensity for taking on challenges. At the same time, women tend to adhere more closely to established rules and norms.

The analysis of spiritual well-being scores reveals that individuals who have converted to Islam within the past two years demonstrate higher scores than those who converted more than two years ago. This intense spiritualism arises during the early stages of faith development, as outlined in Fowler’s theory of Stages of Faith Development, where individuals are in the “synthetic-conventional faith” stage-a phase in which new beliefs are emotionally internalized but not yet fully tested by the complexities of real life [48]. At this point, converts tend to be active in religious worship and activities because they experience faith as a powerful existential force. However, the subsequent decline in spiritual well-being has been attributed to the numerous challenges individuals face after their conversion. These challenges may manifest across various domains, including familial, professional, or social settings, or may be triggered by personal crises arising from shifts in belief systems. Such challenges can indirectly diminish individuals' participation in religious activities, prompting some to question the authenticity of their newly embraced beliefs. Consequently, a dual phenomenon emerges: while certain Muslim converts continue to engage fervently in religious practices to reinforce their faith, others, overwhelmed by internal or external adversities, exhibit reduced levels of engagement. This suggests that, while these individuals retain a Muslim identity, the practical application of their beliefs may be inconsistent or diminished.

This study examines the complex relationship between social support, spiritual well-being, and QoL among Muslim converts, with particular attention to the mediating role of spiritual well-being. The findings indicate a dual influence of social support on QoL, encompassing both a direct effect and an indirect effect mediated by spiritual well-being. These results align with the research of Ke, Liu, and Li [49], which reinforces the critical role of social support in enhancing QoL. Furthermore, Zdun-Ryżewska et al. [50], offer additional insights by highlighting the unique impact of non-relative social support, suggesting that it has a greater efficacy in improving QoL compared to support provided by close family members and relatives.

However, a divergent perspective is presented by Cohen [39], through the stress-buffering hypothesis. This hypothesis suggests that the positive effect of social support on QoL becomes evident only in individuals experiencing stress. In the absence of stress, social support does not appear to have the capacity to directly enhance QoL. The context of Muslim conversion provides a compelling framework for investigating this hypothesis. Converts to Islam, particularly during the early years of their transition, often face numerous stressors, including conflicts with prior belief systems, familial rejection, and challenges within the workplace [2]. This concurs with the observed robust correlation between social support and QoL among converts in this study, thereby endorsing the stress-buffering hypothesis. The findings suggest that social support serves as a buffer against stress, enabling converts to navigate challenges and ultimately enhance their QoL.

Social support exhibits an indirect correlation with QoL, with spiritual well-being acting as a mediator. These results corroborate previous research demonstrating the association between social support and QoL in patients with esophageal cancer [51]. Further studies underscore that perceived social support from various sources, including family, friends, and significant others, positively correlates with two domains of spiritual well-being: meaning (peace) and faith [51]. Specifically, in the context of this research, social support, particularly from family and friends, is crucial for Muslim converts. This support helps individuals navigate the challenges associated with belief transitions, enabling them to effectively adhere to their new beliefs.

Simultaneously, the observed relationship between spiritual well-being and QoL aligns with previous research findings [52, 53], emphasising a positive correlation between spiritual well-being and QoL. Furthermore, high levels of spiritual well-being have been linked to reduced stress and depression [54, 55]. In healthy adults, elevated spiritual well-being is associated with a higher QoL. Consequently, a robust spiritual foundation serves as a strategic coping mechanism for managing adverse environmental circumstances, thereby contributing to the maintenance of individuals’ QoL [54].

5. LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

This study has several limitations. First, the range of scores selected by respondents is relatively narrow compared to the full spectrum of possible scores, indicating a reluctance to choose extreme options such as “Strongly Agree” or “Strongly Disagree.” A considerable proportion of respondents gravitate toward “safe” options, such as “Agree,” “Neutral,” or “Disagree.” The “neutral” category, in particular, may reflect respondents' lack of a definitive answer or decision, as it is open to multiple interpretations (social desirability). Additionally, the inclusion of the “neutral” option (undecided) may contribute to a central tendency effect, where respondents are inclined to select the mean option. Second, this study employs a quantitative approach, which, while valuable, may limit the depth of insights obtained. Future research could benefit from adopting a mixed-methods approach to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the problem. Third, online data collection lies in its susceptibility to sampling bias, particularly due to the exclusion of individuals lacking reliable internet access or sufficient digital literacy. Furthermore, the absence of direct interaction between researchers and participants may lead to misinterpretation of survey items, thereby potentially undermining the validity of the data collected.

Fourth, the majority of respondents had embraced Islam for more than five years, while the number of respondents who had embraced Islam for less than one year was minimal. Including new converts, those who had embraced Islam within the past one to three months, could have enriched the dataset by offering insights into the dynamics of changes in QoL and spiritual intelligence experienced by recent converts. However, the study faced challenges in recruiting new converts, many of whom expressed apprehension or concern about interacting with unfamiliar individuals. Some respondents were hesitant to disclose their status as converts, requesting confidentiality to avoid revealing their condition to family members. The data collection process was extended over six months to ensure the precise estimation of respondents willing to participate. Although the involvement of the Muslim community was anticipated to increase the number of respondents, this expectation was not fully realized.

CONCLUSION

The findings of this research offer a comprehensive and detailed understanding of the intricate dynamics underlying the interplay between social support, spiritual well-being, and QoL among Muslim converts. Notably, the study underscores the critical role of spiritual well-being as a mediating factor in the relationship between social support and QoL. Simultaneously, a direct correlation emerges between social support and QoL, indicating dual pathways through which social support contributes to the enhancement of QoL for Muslim converts. These findings underscore the multifaceted nature of the impact that social support can exert on the well-being of individuals undergoing religious transitions. Furthermore, an intriguing gender-based disparity surfaces, revealing that women exhibit a higher level of spiritual well-being compared to their male counterparts. Additionally, temporal considerations illuminate a compelling facet, wherein recent converts to Islam manifest elevated levels of both QoL and spiritual well-being when contrasted with those who embraced Islam in the more distant past. The insights presented in this study contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the factors influencing the well-being of Muslim converts. Specifically, they illuminate the intricate interplay between social support, spiritual well-being, and the temporal dynamics of belief transition.

The practical implications of these findings include the need to strengthen both formal and informal social support systems for converts, particularly during the first two years following conversion, a critical period for the development of religious identity and psychospiritual stability. Religious institutions and local Muslim communities should actively provide spiritual guidance, religious counseling, and inclusive participatory spaces to help prevent isolation and spiritual fatigue. Additionally, a gender-sensitive approach should be incorporated into intervention strategies, as women tend to exhibit higher levels of spiritual well-being and can thus be empowered to serve as support agents for other converts.

DECLARATION

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT to improve the readability and language of the work. We take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: M.J.: Study conception and design; F.I.N.: Data Analysis or interpretation; H.A.: Methodology; T.T.: Draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| QoL | = Quality of Life |

| WHO | = World Health Organization |

| SWb | = Spiritual Well-being |

| ISEL | = Interpersonal Support Evaluation List |

| MCI | = Indonesian Mualaf Center |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical clearance was granted by the Research Institute of Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta, Indonesia. The ethics approval number is 4558A/B.2/KEPK-FKUMS/XI/2023.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

All the data and supporting information are provided within the article.

FUNDING

This research received funding from Ministry of Higher Education, Indonesia. Funder ID: 006/LL6/PB/AL.04/2023.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.