All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Exploring the Mediating Effects of Gratitude on the Relationship Between Work-life Balance, School Support, and Life Satisfaction among Honorary Teachers

Abstract

Introduction

Life satisfaction reflects an individual’s cognitive evaluation of their current condition. Research on the life satisfaction of honorary teachers in Indonesia remains limited. Concerns regarding low income and career uncertainty highlight the need to explore factors influencing their well-being. This study investigates gratitude as a mediator in the relationship between work-life balance, school support, and life satisfaction among honorary teachers.

Methods

A quantitative approach was employed, using purposive sampling to recruit 284 honorary teachers (79% female, 20.4% male) aged 37–51 years. Participants completed the Work-Life Balance Scale (WLB), School Support Scale (SS), Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6), and Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS). Data were analyzed using Structural Equation Modeling (SEM).

Results

SEM analysis demonstrated a good model fit (df = 435, CFI = 0.957, TLI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.043). Gratitude mediated the relationship between work-life balance and life satisfaction (p = 0.012) and between school support and life satisfaction (p = 0.028).

Discussion

Gratitude plays a significant role in enhancing the life satisfaction of honorary teachers in Indonesia, despite economic pressures and career uncertainty. Study limitations include gender imbalance among participants and a restricted geographical scope.

Conclusion

Work-life balance and school support positively predict life satisfaction, with gratitude functioning as a key mediating factor. These findings underscore the importance of fostering work-life balance, school support, and gratitude to enhance the well-being of honorary teachers.

1. INTRODUCTION

The phenomenon of honorary teachers is unique to Indonesia [1]. There are four categories of teacher status: civil servant teachers (PNS), seconded teachers (DPK), community service teachers, and honorary teachers [2].

Honorary teachers often experience low subjective well-being [3], primarily caused by low job satisfaction and ambiguous employment status. They lack contractual security, receive low salaries, and obtain minimal benefits [4]. These teachers occupy a structurally disadvantaged position compared to their civil servant counterparts, leading to significant social and economic disparities [5].

Nevertheless, many honorary teachers in Indonesia continue to persevere. According to Herzberg’s motivation theory, an individual’s drive to work is not solely determined by salary or income [6]. Intrinsic factors such as achievement, recognition, responsibility, and the nature of the work itself play a critical role in motivation and performance.

Teachers also face both professional and psychological challenges. In the post-COVID-19 era, they struggle to meet competency demands related to technology use. These challenges include adapting to new technologies, managing time and health during technology use, selecting appropriate tools (e.g., VR for education), and designing age-appropriate as well as user-friendly content [7, 8]. Another significant challenge is burnout, which affects their overall well-being [9].

Another finding regarding education in Indonesia comes from the analysis of public sentiment. Positive sentiment relates to public approval of reforms that focus on equity, such as increased funding for schools in rural areas, while negative sentiment reflects dissatisfaction with ongoing policy debates [10].

Life satisfaction is a global cognitive evaluation of one’s life [11], encompassing various domains such as work, income, relationships, and health. Low income is strongly associated with low life satisfaction. One factor that significantly influences life satisfaction is gratitude. Several studies have demonstrated a positive correlation between gratitude and life satisfaction. Research conducted in Spain [12] and Saudi Arabia [13] found that gratitude predicted life satisfaction, reduced stress, and enhanced well-being. In Saudi Arabian adults, gratitude was positively associated with life satisfaction, with social support acting as a mediator [14]. Among young adults, gratitude is likewise positively related to life satisfaction [15]. Altruistic behaviour has also been shown to positively impact happiness and overall well-being [16].

Fredrickson’s theory suggests that gratitude amplifies the positive aspects of life. It is closely linked to happiness [17], helps reduce burnout [18], and promotes prosocial behaviour [19]. In the workplace, gratitude has been associated with access to resources [20], enhanced morale, and a deeper sense of meaning in life [21]. It also contributes to emotional recovery from sadness [22].

Gratitude is strongly influenced by the support received from the school environment. Supportive schools contribute to teachers’ engagement, organisational citizenship behaviour, job satisfaction, commitment, and performance [23]. Teachers’ perceptions of how much the school values their contributions and cares about their well-being shape their overall sense of support [24]. When teachers feel supported, they are more innovative, proactive in addressing challenges, and contribute positively to the school community [25]. Socially supportive environments can also mitigate stress and increase life satisfaction [26], enabling teachers to address diverse student needs effectively [27].

Professional support in schools includes collaborative workshops [28], training, seminars, and peer discussions [29]. When schools provide these supports, teachers tend to feel more satisfied and engaged, highlighting the importance of prioritising supportive environments [30]. Furthermore, providing access to teaching resources and support systems tailored to diverse student needs is essential [31]. Digital support from schools [32], including principal-led digital training [33], enhances teachers’ digital confidence [34]. Technology and professional training have proven essential for effective online teaching and rapid digital adaptation [35], including predicting ROI and improving digital strategies [36].

Emotional support is also critical in enhancing teachers’ personal satisfaction [37]. A school’s organisational climate, characterised by supportive leadership, collaboration, and clear structure, can significantly reduce stress [38], foster positive perceptions of the work environment, and improve performance and satisfaction [39].

Another key factor influencing life satisfaction is work–life balance, defined as the equilibrium between work responsibilities and personal life [40]. Work–life balance improves job autonomy and reduces work–life conflict [41], enabling teachers to manage workloads more efficiently [42], and enhances overall job satisfaction [42]. It also decreases turnover intentions [43].

Work–life balance can increase job satisfaction and reduce turnover intention [44]. Female teachers, in particular, often struggle to balance household responsibilities, childcare, and work obligations, negatively affecting their mental health and satisfaction. Addressing this issue requires a systemic approach that fosters a healthy balance between work and personal life [45], which is essential for teacher well-being [46]. Work–family balance has a significant influence on subjective well-being. Conflict between work and family domains contributes to dissatisfaction and may lead to resignation. To address this, principals should implement strategies to reduce work–family conflict and promote satisfaction and well-being among teachers [47].

The relationships between work–life balance, school support, gratitude, and life satisfaction can be understood through Herzberg’s [48] and Fredrickson’s [49] theoretical frameworks. According to Herzberg’s Two-Factor Theory, motivators (e.g., achievement, recognition, meaningful work) and hygiene factors (e.g., salary, supervision, policies) influence job satisfaction. In this context, work–life balance and school support are external hygiene factors that reduce dissatisfaction and create a positive work environment, while gratitude functions as a motivator by enhancing intrinsic motivation.

Teachers who experience adequate support and work–life balance are more likely to cultivate gratitude, which contributes to greater life satisfaction. Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory posits that positive emotions, such as gratitude, help individuals expand their thought–action repertoires and build lasting personal and social resources. Gratitude thus acts as a psychological bridge, transforming supportive external conditions into internal well-being.

Life satisfaction is a cumulative outcome of both supportive working conditions and a positive psychological state. Based on Herzberg's two-factor theory [50], work–life balance serves as a motivational factor that enhances job satisfaction and overall life satisfaction. Social support theory [51] also highlights how instrumental and emotional support from schools improves psychological well-being and enhances life satisfaction. The broaden-and-build theory further explains that individuals with good work–life balance tend to experience more positive emotions, including gratitude, due to increased perceived harmony and control.

Moreover, gratitude often emerges in response to perceived support, as emphasized by Emmons and McCullough [52], who found that receiving help increases individuals’ tendency to feel grateful. Gratitude, as a positive emotion, helps individuals focus on the good aspects of life, thereby increasing overall life satisfaction. In this study, gratitude acts as a psychological mediator linking external factors (i.e., work–life balance and school support) to life satisfaction. Individuals who receive such support are more likely to develop gratitude, which in turn enhances their overall well-being.

Additionally, several variables, such as mindfulness, empathy [53], hardiness, and social comparison [54], can moderate the relationship between gratitude and life satisfaction. In conclusion, the literature indicates that gratitude mediates the relationship between work–life balance, school support, and life satisfaction among honorary teachers in Indonesia.

Based on the literature review, the following hypotheses are proposed in this study:

H1: Work-life balance has a positive effect on life satisfaction.

H2: School support has a positive effect on life satisfaction.

H3: Work-life balance has a positive effect on gratitude.

H4: School support has a positive effect on gratitude.

H5: Gratitude has a positive effect on life satisfaction.

H6: Gratitude mediates the relationship between work-life balance and school support, and life satisfaction.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Research Design

This study employed a cross-sectional design to examine the role of gratitude as a mediator in the relationship between work–life balance, school support, and life satisfaction among honorary teachers in Indonesia. A purposive sampling technique was used to select participants who met the eligibility criteria, resulting in a total sample of 284 honorary teachers from Salatiga City, Central Java. The statistical analyses included descriptive statistics, regression analysis, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and model fit testing. Data were analysed using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) with JASP software version 0.19.1.

2.2. Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected between October and December 2024 via an online questionnaire distributed through Google Forms and shared via WhatsApp and Instagram platforms. The target population consisted of approximately 800 honorary teachers in Salatiga City, Central Java. Prior to data collection, the researcher obtained official permission from the Head of the Education and Culture Office through a formal request letter. The sample size was determined based on the Krejcie and Morgan sample size table, which recommends a sample of 260–278 for a population ranging from 800 to 1,000. Therefore, 284 respondents were selected for this study to ensure adequate representation.

2.3. Research Instruments

The research instruments used in this study were adapted from the original scales following the adaptation process recommended by the International Test Commission [55], which includes preconditions, test development guidelines, confirmation guidelines, administration guidelines, scoring and interpretation guidelines, and documentation guidelines.

2.3.1. Life Satisfaction

Life Satisfaction was measured using the Indonesian version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale [56]. This instrument assesses the overall level of life satisfaction and consists of 5 items. In this study, the scale demonstrated adequate reliability (α = 0.813, ω = 0.812) and acceptable validity indices (df = 5; p = 0.075; GFI = 0.955; TLI = 0.955; CFI = 0.977).

2.3.2. Gratitude (GQ-6)

Gratitude (GQ-6) was measured using the Indonesian adaptation of the Gratitude Questionnaire [57]. The scale demonstated adequate reliability (α = 0.803, ω = 0.816) and acceptable validity indices (df = 17; p = 0.053; GFI = 0.931; TLI = 0.953; CFI = 0.971).

2.3.3. Work-Life Balance

Work-Life Balance was measured using an adaptation from a previous study [58]. This instrument assesses the overall level of work-life balance, consisting of 7 items. The scale demonstrated good reliability (α = 0.889, ω = 0.873) and acceptable validity indices (df = 19; p = 0.006; GFI = 0.907; TLI = 0.912; CFI = 0.940).

2.3.4. School Support

School Support was measured using an adaptation from a previous study [59]. This instrument evaluates the perceived level of school support and consists of 6 items. The scale showed excellent reliability (α = 0.915, ω = 0.912) and good validity indices (df = 9; p = 0.172; GFI = 0.957; TLI = 0.980; CFI = 0.988).

2.4. Data Analysis Technique

This study employed a quantitative approach using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM) analysis with JASP software. The SEM technique in JASP offers several advantages, including its open-source nature, ease of data import, comprehensive model analysis, integration with lavaan, and automatic visualisation and reporting [60]. The analyses conducted included Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), multiple regression, and mediation analysis. These analyses enabled researchers to examine the relationships and interactions between independent variables (IVs) and dependent variables (DVs).

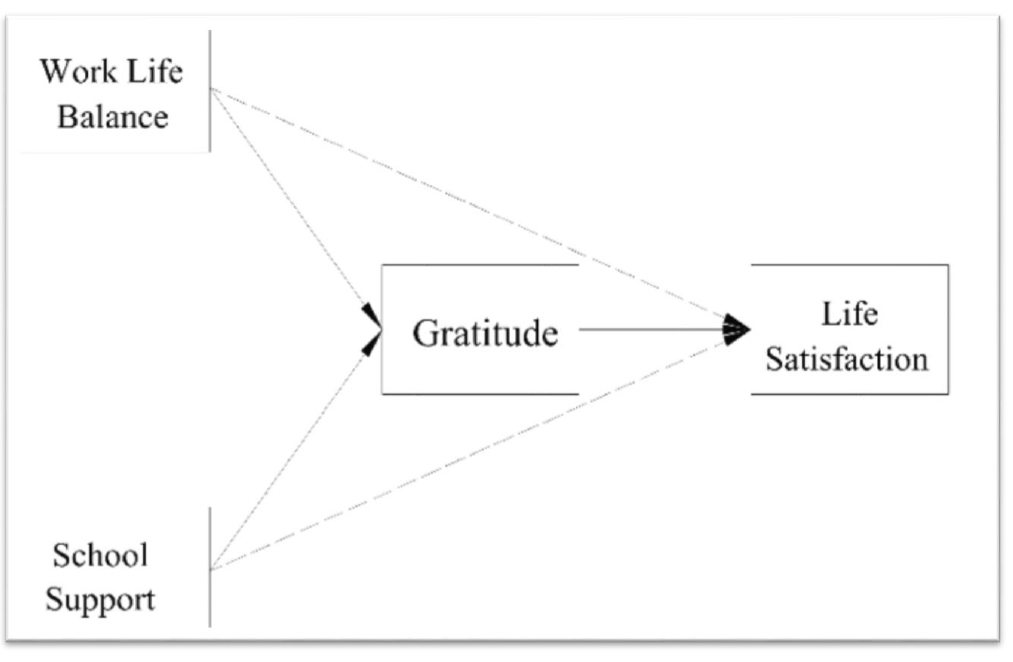

As illustrated in Fig. (1), the independent variables are work–life balance and school support, while the dependent variable is life satisfaction. Gratitude serves as a mediating variable. A mediator variable explains the mechanism or process through which the independent variables influence the dependent variable, clarifying how the relationship occurs between them. This approach enables the examination of interactions involving two or more latent variables [61]. SEM is a robust statistical method that combines elements of path analysis and confirmatory factor analysis. It facilitates the study of complex relationships among latent constructs, variables that are not directly observed but are inferred from measured variables.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A total of 284 honorary teachers from Salatiga City participated in this study (Table 1). Among them, 152 teachers (53%) were aged between 21 and 36 years, 96 teachers (33.8%) were aged 37 to 51 years, and 36 teachers (12.6%) were aged between 52 and 67 years. The sample comprised 226 female honorary teachers (79%) and 58 male honorary teachers (20.4%). Regarding educational background, 18 teachers (6.3%) held a senior high school diploma, 254 teachers (89.4%) held a bachelor’s degree, and 12 teachers (4.2%) held a master’s degree. In terms of teaching experience, 81 teachers (28.5%) had less than five years of service, while 203 teachers (71.4%) had more than five years of service.

Proposed research model.

| Characteristics | N |

|---|---|

| Age | - |

| 21-36 years | 152 (53%) |

| 37-51 years | 96 (33,8%) |

| 52-67 years | 36 (12,6%) |

| Gender | - |

| Female | 226 (79%) |

| Male | 58 (20,4%) |

| Education | - |

| High School/Diploma | 18 (6,3%) |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 254 (89,4%) |

| Master’s Degree | 12 (4,2%) |

| Years of Service | - |

| Less than 5 years | 81 28,5%) |

| More than 5 years | 203 (71,4%) |

Reliability tests for the variables were conducted using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega. The reliability values for each variable are presented in Table 2. The work–life balance variable demonstrated α = 0.889 and ω = 0.902, while the school support variable recorded α = 0.915 and ω = 0.917. The gratitude variable showed α = 0.816 and ω = 0.870, and the life satisfaction variable had α = 0.813 and ω = 0.851.

| Variables | Item Total | Cronbach’s α | McDonald’s ω |

|---|---|---|---|

| Worklife balance | 7 | 0,889 | 0,902 |

| School support | 6 | 0,915 | 0,917 |

| Gratitude | 7 | 0,816 | 0,870 |

| Life satisfaction | 5 | 0,813 | 0,851 |

The item validity tests for each variable are presented in Table 3, based on the estimated factor loading values. The item validity for the work–life balance variable ranged from 0.409 to 0.523; for the school support variable, the values ranged from 0.406 to 0.617; for the gratitude variable, from 0.319 to 0.454; and for the life satisfaction variable, from 0.367 to 0.544.

| - | Confidence Interval 95% | - | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor Loading | Indicator | Estimate | Standar Error | Z-Value | p | Lower | Upper | Std. Est. (All) |

| WLB (X1) | I1 | 0.447 | 0.052 | 8.530 | < 0.001 | 0.345 | 0.550 | 0.502 |

| I2 | 0.454 | 0.033 | 13.967 | < 0.001 | 0.390 | 0.518 | 0.738 | |

| I3 | 0.500 | 0.038 | 13.006 | < 0.001 | 0.425 | 0.575 | 0.702 | |

| I4 | 0.462 | 0.032 | 14.578 | < 0.001 | 0.400 | 0.524 | 0.762 | |

| I5 | 0.483 | 0.031 | 15.628 | < 0.001 | 0.422 | 0.544 | 0.798 | |

| I6 | 0.485 | 0.035 | 13.689 | < 0.001 | 0.415 | 0.554 | 0.730 | |

| I7 | 0.409 | 0.032 | 12.935 | < 0.001 | 0.347 | 0.471 | 0.702 | |

| I8 | 0.523 | 0.032 | 16.364 | < 0.001 | 0.460 | 0.585 | 0.823 | |

| SS (X2) | I1_10 | 0.406 | 0.031 | 13.285 | < 0.001 | 0.346 | 0.466 | 0.707 |

| I2_11 | 0.617 | 0.037 | 16.786 | < 0.001 | 0.545 | 0.689 | 0.831 | |

| I3_12 | 0.571 | 0.031 | 18.137 | < 0.001 | 0.509 | 0.633 | 0.875 | |

| I4_13 | 0.483 | 0.031 | 15.708 | < 0.001 | 0.423 | 0.543 | 0.796 | |

| I5_14 | 0.535 | 0.032 | 16.574 | < 0.001 | 0.471 | 0.598 | 0.829 | |

| I6_15 | 0.486 | 0.033 | 14.830 | < 0.001 | 0.422 | 0.551 | 0.766 | |

| Gratitude (M) | I1_30 | 0.376 | 0.033 | 11.406 | < 0.001 | 0.311 | 0.440 | 0.643 |

| I2_31 | 0.354 | 0.033 | 10.871 | < 0.001 | 0.290 | 0.418 | 0.629 | |

| I3_32 | 0.413 | 0.028 | 14.848 | < 0.001 | 0.359 | 0.468 | 0.785 | |

| I4_33 | 0.413 | 0.030 | 13.815 | < 0.001 | 0.355 | 0.472 | 0.748 | |

| I5_34 | 0.454 | 0.029 | 15.671 | < 0.001 | 0.397 | 0.511 | 0.811 | |

| I6_35 | 0.372 | 0.046 | 8.050 | < 0.001 | 0.282 | 0.463 | 0.480 | |

| I9_39 | 0.319 | 0.029 | 11.164 | < 0.001 | 0.263 | 0.375 | 0.633 | |

| LS (Y) | I1_42 | 0.521 | 0.037 | 14.238 | < 0.001 | 0.449 | 0.593 | 0.750 |

| I2_43 | 0.544 | 0.032 | 17.126 | < 0.001 | 0.482 | 0.607 | 0.851 | |

| I3_44 | 0.513 | 0.032 | 16.002 | < 0.001 | 0.451 | 0.576 | 0.813 | |

| I4_45 | 0.495 | 0.032 | 15.381 | < 0.001 | 0.432 | 0.558 | 0.792 | |

| I5_46 | 0.367 | 0.056 | 6.565 | < 0.001 | 0.257 | 0.476 | 0.392 | |

| - | Estimate | Std. Error | Z value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M→ Y | 0.173 | 0.056 | 3.088 | 0.002 |

| X1→ Y | 0.075 | 0.015 | 4.846 | < 0.001 |

| X2→ Y | 0.088 | 0.020 | 4.412 | < 0.001 |

| X1→ M | 0.072 | 0.017 | 4.323 | < 0.001 |

| X2→ M | 0.066 | 0.023 | 2.932 | 0.003 |

The results of the hypothesis testing are presented in Table 4. The first hypothesis test indicates that work–life balance has a direct positive effect on life satisfaction, with a significance value of 0.001, which is less than 0.05. A better work–life balance positively influences teachers’ sense of gratitude, which in turn enhances their life satisfaction. Previous research [62] supports this finding, showing that work–life balance positively affects gratitude. A higher level of work–life balance is associated with greater gratitude among female teachers. There is also a significant relationship between job satisfaction and quality of life [63]. Since the teaching profession is predominantly female, with many teachers holding multiple roles as educators, mothers, and wives, balancing work and life is crucial. This balance can be facilitated by schools through flexible scheduling policies.

Schools can support female teachers by helping them balance family life and work, providing opportunities for religious practice, and facilitating continuing education or competency development. When effectively implemented, such supports contribute to greater happiness and satisfaction. Furthermore, the potential of metaverse technology to foster more interactive and immersive learning environments has relevant implications for teachers’ work–life conditions, particularly within virtual work settings [64].

The second hypothesis test shows that school support has a significant effect on life satisfaction, with a significance value of 0.001, which is less than 0.05. Previous research also indicates a correlation between school support and life satisfaction among teachers [65]. School support encompasses innovative approaches to assessing perceptions of organisational services through machine learning-based sentiment analysis. This methodology can be applied in educational contexts to better understand and enhance the organisational support perceived by teaching and administrative staff [66]. School support positively influences work commitment and innovative work behaviour [67]. It also acts as a mediator between gratitude and teachers’ life satisfaction [68]. When employees feel supported by their organisation, they are more likely to experience gratitude, which in turn increases their engagement and commitment to the organisation [69].

Understanding how school support influences these dynamics is essential for fostering expressions of gratitude among employees in the workplace [70]. When employees perceive genuine intentions behind the support provided, their sense of gratitude tends to increase [71].

The third hypothesis test indicates that work–life balance has a significant effect on gratitude, with a significance value of 0.001, which is less than 0.05. Work–life balance within school systems has the potential to foster positive emotions such as gratitude. Research by [62] found that work–life balance has a positive influence on gratitude among female teachers in secondary schools. Gratitude has also been shown to mediate the relationship between Islamic work ethics and religiosity in reducing work–life conflict, underscoring its importance in the professional context of women [72]. In addition, gratitude moderates the relationship between work–family conflict and both life satisfaction and happiness among nurses, acting as a protective factor that strengthens subjective well-being despite conflicts between work and family life [73]. Furthermore, practising gratitude enhances the subjective well-being of IT professionals through the mediation of employee engagement. Gender has also been found to moderate this relationship, suggesting that the impact of gratitude on well-being may vary across genders [74].

The fourth hypothesis test shows that school support has a significant effect on gratitude, with a significance value of 0.003, which is less than 0.05. A supportive school environment creates a positive climate that fosters emotions such as gratitude. Research findings indicate that a positive school climate enhances gratitude among adolescents, which in turn encourages prosocial behaviour. Gratitude fully mediates the relationship between school climate and prosocial behaviour [75].

The fifth hypothesis test indicates that gratitude has a significant effect on life satisfaction, with a significance value of 0.002, which is less than 0.05. Previous research has shown that gratitude is positively correlated with life satisfaction among university students [76]. Adolescents with higher levels of gratitude experience greater life satisfaction [77]. A strong sense of gratitude helps students maintain stable life satisfaction even in the presence of cyberbullying [78]. Life satisfaction also acts as a protective factor in stressful life events [9]. Among working individuals, including practitioners, teachers, and nurses, a significant correlation exists between gratitude and life satisfaction [79]. Practicing gratitude effectively increases positive affect and life satisfaction, while reducing negative affect [14]. In adults and elderly individuals, gratitude is also positively and significantly correlated with life satisfaction [80].

Table 5.

| - | Estimate | Sth.Eror | Z value | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Effect | ||||

| X1→ Y | 0.075 | 0.015 | 4.846 | < 0.001 |

| X2→ Y | 0.088 | 0.020 | 4.412 | < 0.001 |

| Indirect Effect | ||||

| X1→M→ Y | 0.012 | 0.005 | 2.521 | 0.012 |

| X2→M→ Y | 0.011 | 0.005 | 2.201 | 0.028 |

| Total Effect | ||||

| X1→ Y | 0.087 | 0.015 | 5.882 | < 0.001 |

| X2→ Y | 0.100 | 0.019 | 5.183 | < 0.001 |

The sixth hypothesis test reveals that work–life balance is associated with life satisfaction through gratitude as a mediating variable, with a significance value of 0.012 (< 0.05). It also shows that school support is correlated with life satisfaction through gratitude as a mediator, with a significance value of 0.028 (< 0.05). Overall, both work–life balance and school support are directly related to life satisfaction and indirectly related to it through gratitude (Table 5).

The model fit test using SEM in JASP was conducted through several steps: opening JASP, importing the CSV data, ensuring that the Likert scale items were set as ordinal, writing the syntax, selecting the WLSMV estimator for ordinal items, and activating FIML to handle missing data. The fit indices were assessed by examining the Chi-square, CFI, TLI, RMSEA, and SRMR values. In the JASP output, the CFI and TLI values are displayed in the “Fit Indices” table, whereas the RMSEA and SRMR are shown in the “Other Fit Measures” table.

Model fit testing indicates that the proposed model is appropriate, with fit indices as follows: CFI = 0.957, TLI = 0.951, RMSEA = 0.043, and GOF = 0.989. These indices meet the recommended criteria for model fit according to Hu and Bentler [81]. Gratitude functions as a significant mediator in the conceptual model of this study. This finding is consistent with previous research demonstrating that gratitude mediates the relationship between various time perspectives and life satisfaction [82, 83]. Gratitude also mediates the relationship between forgiveness and life satisfaction among university students, underscoring its role in enhancing psychological and emotional well-being (Tables 6 and 7) [84].

| Indeks | Value |

|---|---|

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 0.957 |

| Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) | 0.951 |

| Bentler-Bonett Non-normed Fit Index (NNFI) | 0.951 |

| Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI) | 0.886 |

| Parsimony Normed Fit Index (PNFI) | 0.780 |

| Bollen Relative Fit Index (RFI) | 0.871 |

| Bollen Incremental Fit Index (IFI) | 0.957 |

| Relative Non-Centrality Index (RNI) | 0.957 |

| Metrics | Value |

|---|---|

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.043 |

| RMSEA 90% CI lower bound | 0.036 |

| RMSEA 90% CI upper bound | 0.050 |

| RMSEA p-value | 0.945 |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.051 |

| Hoelter’s Critical N (α = 0.05) | 208.627 |

| Hoelter’s Critical N (α = 0.01) | 218.620 |

| Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) | 0.989 |

| McDonald’s Fit Index (MFI) | 0.697 |

| Expected Cross-Validation Index (ECVI) | 2.858 |

Furthermore, gratitude has been shown to enhance interpersonal relationships and promote prosocial behaviour, functioning as a mediator distinct from other emotions such as elevation and awe [85]. It also mediates the relationship between personality traits and responses to gratitude-based interventions, underscoring the importance of considering individual differences in the effectiveness of such interventions. Ultimately, gratitude may motivate individuals to engage in positive behaviours that foster personal growth and development [86].

4. RESEARCH LIMITATIONS

This study has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting its findings. First, there was an unequal gender distribution among participants, with female honorary teachers comprising 79% of the sample, while male teachers represented only 20.4%. This gender imbalance may limit the generalisability of the findings to the broader population of honorary teachers, particularly regarding gender-specific work experiences. Second, the research sample was drawn from a single city in Central Java, restricting the geographical scope of the study. Consequently, sociocultural and institutional variations from other regions were not represented, limiting the external validity of the findings. Third, while the study confirmed that gratitude contributes to higher life satisfaction among honorary teachers, it cannot yet be regarded as the primary mechanism influencing life satisfaction. Other psychological or organisational factors, such as work engagement, job demands, or organisational climate, were not examined within this model. A theoretical gap remains, as the study did not consider potential moderating or mediating contextual variables, including workload, organisational support, or leadership style, which may also influence the relationship between work–life balance, school support, and life satisfaction. Furthermore, the study employed a cross-sectional design, limiting the ability to capture long-term effects or establish causal relationships over time.

CONCLUSION

Despite the low salaries and career uncertainty experienced by honorary teachers in Indonesia, the findings of this study demonstrate that gratitude significantly contributes to enhancing their life satisfaction. In addition to gratitude, the implementation of work–life balance systems is crucial, particularly given that the majority of honorary teachers are women who often face multiple role conflicts as educators, mothers, and wives. Supportive work–life balance policies can help reduce these role-related tensions. Moreover, exploring dynamic discourse on virtual work environments would enhance the contextual understanding of teachers’ work–life conditions [87].

Furthermore, school support plays a crucial role in enhancing the well-being of honorary teachers. This support encompasses not only professional development opportunities but also emotional assistance, which fosters a sense of comfort and belonging within the professional environment. The findings of this study provide a practical foundation for school administrators to strengthen both internal factors, such as cultivating gratitude among teachers, and external factors, such as implementing work-life balance policies and providing institutional support. By addressing these areas, schools can effectively improve the overall life satisfaction of their honorary teaching staff.

Although previous studies have explored the individual effects of gratitude, work–life balance, and organisational support on employee well-being, there remains a lack of integrated models that examine how gratitude functions as a mediator in the relationship between work–life balance, school support, and life satisfaction, particularly within the context of honorary teachers in developing countries such as Indonesia. Most existing literature also underrepresents gender-specific challenges in the teaching profession, especially for women juggling multiple social roles. This study helps bridge that gap by highlighting the mediating role of gratitude and addressing the unique needs of female honorary teachers through a culturally relevant lens.

Our findings align with recent evidence that gratitude functions not only as a predictor of mental well-being, mediating life satisfaction [88], but also as a moderator that strengthens the positive impact of work–life balance on happiness and life satisfaction [73].

PRACTICAL RECOMMENDATIONS

- School administrators are encouraged to implement family-friendly work policies that promote work–life balance, including flexible scheduling as well as emotional and professional support, particularly given the dual roles many female honorary teachers hold as educators, mothers, and wives.

- Positive psychology–based training, including gratitude and mindfulness programs, should be incorporated into teacher development initiatives to enhance psychological resilience and improve life satisfaction.

- The Department of Education is advised to develop comprehensive welfare programs for honorary teachers that address not only financial needs but also emotional and psychological well-being.

THEORETICAL AND FUTURE RESEARCH RECOMMENDATIONS

- Future research should include more representative and geographically diverse samples, involving teachers from various cities and regions, to capture contextual differences and enhance generalizability.

- The conceptual model could be expanded by integrating additional variables, such as job demands, work engagement, and school leadership, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing life satisfaction among honorary teachers.

- Longitudinal and mixed-methods research designs are recommended to investigate the evolving effects of gratitude, work-life balance, and organizational support over time, while also providing deeper insights into the personal and professional challenges faced by honorary teachers.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: T.K.: Study conception and design; L.R.: Analysis and interpretation of results; Q.A.: Writing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| WLB | = Work–Life Balance Scale |

| SSS | = School Support Scale |

| GQ-6 | = Gratitude Questionnaire |

| SWLS | = Satisfaction With Life Scale |

| SEM | = Structural Equation Modelling |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The study involving human participants was reviewed and approved by the the Research Ethics Committee (KEPK) of the Faculty of Health Sciences, Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta, Indonesia under approval number No. 663/KEPK-FIK/XI/2024.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of this article is available in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository at the following link: https://osf.io/e3g2d/files/osfstorage/ 690d726b079b3c0b0e96c87e Reference number: OSF Project ID e3g2d.

FUNDING

This research was funded by BIMA – Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology (Kemdikbudristek), Republic of Indonesia under the research grant scheme. Funder name: BIMA – Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology (Kemdikbudristek). Grant number: 108/E5/PG.02.00.PL/2024

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.