All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Adverse Childhood Experiences and Executive Functioning in Chinese Adolescents: The Mediating Role of Emotional States

Abstract

Introduction

While adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are known to impair executive functioning (EF), the precise emotional mechanisms are underexplored. This study investigated the parallel mediating roles of positive and negative emotions in the ACEs-EF link and formally compared their relative influence on Chinese adolescents.

Methods

Using a cross-sectional design, 683 adolescents with a history of adversity completed self-report measures for ACEs, emotional states, and EF. A parallel mediation model was tested via structural equation modeling, with a 5,000-resample bootstrap procedure used to evaluate indirect effects.

Results

The analysis revealed significant indirect effects of ACEs on EF through both diminished positive emotion (β = −.038, 95% CI [−.049, −.029]) and elevated negative emotion (β = −.057, 95% CI [−.072, −.045]). Critically, the pathway through negative emotion was confirmed to be significantly stronger (Difference = .019, 95% CI [.005, .034]), although a significant direct ACEs-EF path remained.

Discussion

These findings provide robust evidence that emotional states are a primary mechanism transmitting risk from ACEs to EF impairment. The novel demonstration that negative emotion is a more potent mediator is a key contribution to the field.

Conclusion

This highlights the need for interventions that not only foster positive affect but also prioritize strategies aimed at mitigating and regulating negative emotions to buffer the neurocognitive consequences of childhood adversity.

1. INTRODUCTION

Over the past few decades, executive functioning (EF) in minors has become a widely studied variable in psychology and medicine, particularly in children and adolescents [1, 2]. EF, also known as cognitive or executive control, refers to a set of top-down neurocognitive processes that contrast with bottom-up instinctual actions. These functions are essential for decision-making and engaging in purposeful, goal-directed behavior [3, 4]. EF plays a crucial role in various aspects of lifelong development and is considered an important cognitive resource, influencing academic achievement [5], social and emotional competence [6, 7], and physical and mental health [8, 9].

However, despite the widely recognized importance of EF, there is still no consensus in the academic community regarding its component theory, and discussions about its definition have persisted in recent years [10]. While debates continue [10, 11], most scholars agree that EF comprises three core components: inhibition, updating, and shifting [3]. As research has progressed, non-cognitive factors also been incorporated into discussions on EF. For example, with the introduction of emotional components, EF is now categorized into two types: “cool” EF, which primarily involves cognitive processes [12], and “hot” EF, which involves emotional engagement [13]. Due to ongoing theoretical differences, the specific components of EF often vary depending on the tools used by researchers and the objectives of the study. It is worth noting that the conceptualization of EF in different studies frequently depends on the type of research tools employed. When the focus is on ability and function, experiments are typically used, and the term “executive function” is applied; when the focus is on process and performance, scales are typically used, and the term “executive functioning” is applied. Nonetheless, these two terms essentially refer to the same concept and can be used interchangeably in certain contexts [14]. Additionally, there is still a lack of sufficient research exploring EF through the use of various types of scales [15].

Adolescence is a crucial stage in lifelong development, marked by a rapid increase in cognitive abilities and physiological development that often outpaces psychological maturity. This discrepancy leads to a range of characteristics, including intense emotional fluctuations, heightened sensitivity, increased rebelliousness, rich emotions, high susceptibility, and strong exploratory tendencies [16]. Adolescence is also a critical period for the development of executive functioning (EF) [17, 18]. For instance, the basic components of EF reached near-adult levels before adolescence [19], which is why there is a wealth of research focused on EF in infants and children [14, 20]. However, complex EF, which emerges from the interaction of basic EF components, continues to develop throughout adolescence [18]. Due to the lack of effective measures for assessing complex components, there is also a relative shortage of research on the basic components of EF in adolescents.

The long-term negative effects of early life adversity—a phenomenon defined as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) encompassing abuse, neglect, and severe household dysfunction—represent a major global health challenge [21]. A wealth of international evidence confirms a cumulative risk model, whereby a greater number of ACEs predict heightened vulnerability to a wide array of mental and physical health problems throughout an individual’s life [22]. A critical, yet often overlooked, casualty of early adversity is neurocognitive development [23], particularly the domain of executive functioning (EF) [20]. Executive functions are a suite of higher-order cognitive abilities (e.g., working memory, inhibitory control, cognitive flexibility) that are foundational for goal-directed behavior, academic achievement, and lifelong well-being [4]. The “toxic stress” model provides a robust theoretical framework for this connection [24], positing that chronic activation of the stress-response system disrupts the maturation of the prefrontal cortex, the primary neural substrate for EF [25].

In line with this framework, a wealth of global evidence confirms a strong negative association between ACEs and EF deficits [1]. This is a particularly pressing concern in non-Western contexts like China [26], where recent epidemiological data suggest a high prevalence of ACEs [27], underscoring the urgency of understanding their impact on adolescents, the scope of exposure to childhood adversity is extensive, with studies indicating that roughly half of all individuals experience at least one such event. Critically, more than 30% of the population accumulates a high burden of several types of ACEs [28], a level of exposure that researchers have identified as dramatically increasing the risk for subsequent mental illness and deficits in neurodevelopment. However, while the link between ACEs and impaired EF is well-documented, the precise psychological mechanisms that transmit this risk remain inadequately specified [29]. Elucidating these intermediate pathways is a critical step toward designing effective, targeted interventions to mitigate the long-term cognitive consequences of childhood adversity.

We believe that among the most plausible mechanisms are disruptions in emotional states [30]. Exposure to chronic adversity in childhood fundamentally alters affective development [31], often leading to a diminished capacity for experiencing positive emotions [32] and a heightened vulnerability to negative emotions [33]. This emotional experience is often based on a severely impaired ability to regulate emotions [34]. This affective imbalance can takeover finite cognitive resources essential for EF [13]. For instance, persistent negative affect may foster rumination, thereby depleting working memory [35], while an absence of positive affect can impair cognitive flexibility and creative problem-solving [36]. Despite this, much of the existing literature has either focused exclusively on the mediating role of negative affects (e.g., depression, anxiety) or failed to model positive and negative affect as distinct pathways [37]. This is a significant limitation, as distinguishing between these two dimensions is crucial for both theoretical clarity and the development of nuanced interventions.

Despite growing interest in this area, two critical gaps in the literature persist. First, few studies have simultaneously modeled and formally compared the mediating strength of positive versus negative emotions, leaving it unclear whether they contribute equally to EF deficits following adversity. Second, research in this domain has been overwhelmingly conducted in Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) societies [38]. This geographical and cultural imbalance is problematic, as norms surrounding emotional expression, regulation, and coping vary significantly across cultures [39]. Investigating these pathways in a Chinese context is therefore essential to determine the universality and cultural specificity of the mechanisms linking adversity to cognitive outcomes.

The primary aim of this research was, therefore, to disentangle the respective mediating effects of positive and negative emotions on the established association between ACEs and EF. This objective was pursued using a parallel mediation design with a large sample of Chinese adolescence students, a context where such specific pathways remain underexplored. We aimed to: (1) establish the associations among ACEs, emotional states, and EF in this understudied population; (2) test a parallel mediation model where both positive and negative emotions were specified as independent mediators; and (3) formally compare the magnitude of these two indirect effects. We hypothesized that both positive and negative emotions would significantly mediate the relationship between ACEs and EF. Critically, based on the robust link between trauma and pathological negative affect, we further hypothesized that negative emotion would emerge as the more potent, or dominant, mediating pathway.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Participant

As a classic cross-sectional quantitative research, we initially recruited 1,200 adolescents aged 12-17 via cluster sampling from several middle and high schools in China's Hebei and Hainan provinces. Cluster sampling is done by organizing the total number of classes in each grade level, followed by a computerized random sampling of classes in each grade level. . We collected data by asking teachers of mental health programs in selected schools to select current students in full compliance with their campus rules and personal wishes. This recruitment process involved a two-step screening: first, teachers with long-term contact confirmed that students had no known neuropsychological conditions via verbal inquiry. Participants were then screened using the Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACE-Q). To ensure our analysis concentrated on a specific population, we established an inclusion criterion requiring a history of at least one ACE. This screening process yielded a final analytical sample of 683 adolescents. A prospective power analysis conducted in G*Power 3.1 confirmed that this sample size provided ample statistical power for the planned correlational and regression models, ensuring the reliability of our findings.

2.2. Study Design

Data collection occurred in classroom groups under standardized conditions to minimize fatigue and response bias. Trained researchers provided standardized instructions, emphasizing the anonymity and voluntary nature of participation. To ensure data quality, we implemented and clearly defined our exclusion criteria. Participants were excluded for substantial missing data (over 20% of items on any single scale), patterned responding (e.g., straight-lining on 80% or more of items), or failure on embedded validity check items. Completed questionnaires were securely stored, and all data were entered using a double-check protocol, with 10% of entries randomly audited for accuracy.

Our analytical strategy began with model validation, where we conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) in AMOS 23.0 to confirm the first- and second-order factor structure of our scales. Following this, we calculated Bonferroni-corrected correlations and descriptive statistics in SPSS 25.0. The core of our analysis involved a parallel mediation model tested via structural equation modeling (SEM). Within this model, we used a 5,000-resample bootstrap procedure to estimate the significance of the pathways. A key component of this model was a formal comparison of the two indirect effects, achieved by computing a user-defined estimand for the difference between the mediation coefficients.

2.3. Research Tools

2.3.1. Adverse Childhood Experiences Scales

2.3.1.1. Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACE-Q)

We administered the 10-item Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire (ACE-Q) primarily as a screening tool to identify a sample suitable for this study [21]. The measure assesses exposure to various forms of abuse (psychological, physical, sexual) and household dysfunction (e.g., domestic violence, substance use, incarceration), with each “yes” response scored as 1. Only individuals with a cumulative score of one or higher were retained for the final analyses.

2.3.1.2. Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form

(CTQ-SF) CTQ-SF was used to measure five specific forms of childhood maltreatment: emotional/physical neglect and emotional/physical/sexual abuse. Its 25 items are rated on a 5-point frequency scale (1 = ‘never’ to 5 = ‘always’) [40]. A key feature of the CTQ is its use of validated subscale thresholds (e.g., emotional abuse ≥13, sexual abuse ≥8) to classify experiences as clinically significant. The psychometric soundness of the CTQ in our at-risk sample was confirmed, as all subscales yielded Cronbach’s alpha coefficients above .80.

2.3.2. Emotional Status Scale

2.3.2.1. Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS)

Participants’ emotional states were assessed using PANAS [41]. The PANAS consists of two 10-item subscales designed to quantify distinct dimensions of positive and negative affect. Respondents rated the intensity of their feelings on a 5-point scale, where higher scores reflect greater levels of the corresponding affective state. The selection of this instrument was supported by prior research confirming its robust psychometric properties and cultural validity among Chinese adolescent populations [42, 43]. Reinforcing its suitability for our sample, both the positive affect and negative affect subscales demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current study (α > 1.90).

2.3.3. Executive Functioning Scale

2.3.3.1. Executive Functioning Scale (EFS)

This study used the Executive Functioning Scale (EFS) developed by Thomas-W., Uljarević, et al. [44] to assess EF. EFS consists of 52 items that assess key aspects of EF in children and adolescents. In this study, the scale was adapted to a self-assessment format, with Cronbach's alpha coefficients exceeding 0.80 for all dimensions. The EFS uses a five-point Likert scale, from “never” to “very frequently.” The total score indicates overall performance, covering six components: working memory, risk avoidance, response inhibition, emotional regulation, set shifting, and processing speed.

Since this scale has not yet been widely used in Chinese contexts, to ensure the cultural and linguistic appropriateness of the Executive Functioning Scale (EFS) for our sample, a rigorous adaptation process was undertaken, following established psychometric guidelines. This multi-stage process included forward-translation into Chinese, a blind back-translation by an independent bilingual expert, and a consensus meeting with a panel of educational psychology scholars to reconcile any discrepancies and refine item wording. Key modifications were made to enhance ecological validity and developmental appropriateness. For example, items featuring culturally specific Western activities (e.g., “baking”) were replaced with more universally relevant counterparts (e.g., “cooking”). Similarly, items originally designed for younger children were rephrased into more complex, scenario-based questions suitable for the cognitive level of adolescents. Careful consideration was given to items assessing emotional regulation, which were adapted to reflect cultural nuances in emotional expression (e.g., rephrasing a direct statement about anxiety to a more internalized description of being “immersed in sadness”). These iterative refinements were designed to maintain the construct integrity of the original scale while ensuring the final items were comprehensible, relevant, and culturally sensitive to Chinese adolescents. The strong internal consistency reported for the EFS provides initial evidence for the success of this adaptation process.

2.4. Analysis Plan

The analysis was conducted sequentially in three stages to test the mediating effect hypothesis of the sentiment hypothesis:

2.4.1. Phase I: Construct Validity Testing of Study Instruments (CFA) Latent Variable Construction

ACEs: Two latent factors—abuse (emotional/physical/sexual) and neglect (emotional/physical). EF: Six EFS subscales loaded onto a second-order EF factor. Residual covariances allowed between theoretically linked items (e.g., working memory and processing speed). Model Fit Evaluation: Criteria: χ2/df <3, CFI/TLI >0.90, RMSEA <0.08, etc (Table 1). Calculation of structural validity of scales involved structural equation modeling (Table 2).

2.4.2. Phase II: Preliminary Analyses

The preliminary analysis phase was designed to establish a descriptive and correlational foundation for our model. To describe the data, we generated summaries of participants’ sociodemographics (Table 3), ACEs subtype prevalence (Table 4), and the central tendencies of our main variables (Table 5). To establish foundational relationships, we conducted a Pearson correlation analysis across ACEs, positive/negative emotions (PE/NE), and EF (Table 6). The significance of this matrix was evaluated against a rigorous Bonferroni-corrected alpha level of .001 to control for the probability of Type I error.

| - | CMIN/DF | RMR | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | <3.000 | <.050 | >.900 | >.900 | <.080 |

| Variables | CMIN/DF | RMR | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEs (CTQ-SF) | 1.905 | .038 | .972 | .974 | .036 |

| Emotion (PANAS) | 2.772 | .030 | .961 | .965 | .051 |

| EF (EFS) | 1.447 | .047 | .975 | .976 | .026 |

| Demographic Variables | Construct | Number/% |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 341 (49%) |

| Female | 342 (51%) | |

| Age group | Middle adolescence (12-14 years old) | 322 (47%) |

| Late adolescence (15-17 years old) | 361 (53%) | |

| Father’s education level | Below undergraduate | 252 (37%) |

| B.A./B.S. | 325 (48%) | |

| M.A./M.S. | 63 (9%) | |

| Ph.D. | 43 (6%) | |

| Mother’s education level | Below undergraduate | 263 (39%) |

| B.A./B.S. | 341 (50%) | |

| M.A./M.S. | 44 (6%) | |

| Ph.D. | 35 (5%) | |

| Family annual income | 0~25M | 182 (27%) |

| 25~40M | 479 (70%) | |

| Over 40M | 22 (3%) |

| ACE | Male (N) / % | Female (N) / % |

|---|---|---|

| Emotional abuse | 113 (33%) | 107 (31%) |

| Physical abuse | 125 (37%) | 111 (32%) |

| Sexual abuse | 15 (4%) | 10 (3%) |

| Emotional neglect | 128 (37%) | 130 (38%) |

| Physical neglect | 112 (32%) | 116 (34%) |

| Parental separation or divorce | 20 (5%) | 30 (9%) |

| Mother treated violently | 110 (32%) | 104 (30%) |

| Household substance abuse | 112 (33%) | 103 (30%) |

| Household member imprisoned | 10 (2%) | 15 (4%) |

| Household mental illness | 25 (8%) | 20 (5%) |

| Variable Name | M±SD |

|---|---|

| Emotional abuse | 18.56 ± 4.84 |

| Physical abuse | 18.61 ± 4.70 |

| Sexual abuse | 16.61 ± 5.21 |

| Emotional neglect | 12.54 ± 4.54 |

| Physical neglect | 15.27 ± 4.77 |

| Positive emotion | 26.77 ± 8.42 |

| Negative emotion | 26.82 ± 7.83 |

| Working memory | 3.78 ± 0.99 |

| Risk avoidance | 3.70 ± 1.07 |

| Response inhibition | 3.85 ± 0.97 |

| Emotional regulation | 3.72 ± 1.03 |

| Set shifting | 3.83 ± 0.97 |

| Processing speed | 3.71 ± 1.09 |

| Executive functioning | 196.39 ± 41.15 |

| Variables | Emotional Abuse | Physical Abuse | Sexual Abuse | Emotional Neglect | Physical Neglect | Positive Emotion | Negative Emotion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive emotion | -.409** | -.415** | -.346** | -.330** | -.315** | - | - |

| Negative emotion | .458** | .485** | .387** | .402** | .390** | - | - |

| Working memory | -.376** | -.386** | -.418** | -.199** | -.366** | .425** | -.452** |

| Risk avoidance | -.339** | -.328** | -.335** | -.133** | -.275** | .362** | -.409** |

| Response inhibition | -.382** | -.324** | -.344** | -.178** | -.360** | .395** | -.450** |

| Emotional regulation | -.350** | -.382** | -.400** | -.178** | -.340** | .370** | -.481** |

| Set shifting | -.304** | -.326** | -.371** | -.184** | -.303** | .364** | -.473** |

| Processing speed | -.358** | -.353** | -.344** | -.190** | -.332** | .385** | -.439** |

| Executive functioning | -.445** | -.448** | -.479** | -.227** | -.422** | .492** | -.573** |

| Structure | CMIN/DF | RMR | GFI | AGFI | IFI | TLI | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fig. (1) | 2.936 | 1.21 | .962 | .945 | .967 | .959 | .967 | .053 |

| - | Estimate | Lower | Upper | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACEs-PE-EF | -.038 | -.049 | -.029 | .000 |

| ACEs-NE-EF | -.057 | -.072 | -.045 | .000 |

| Total Effect | -.126 | -.145 | -.107 | .000 |

| Difference (PE-NE) | .019 | .005 | .034 | .005 |

2.4.3. Phase III: Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) and Mediation Effects Tests

In the final analytical phase, we tested our primary hypotheses using a parallel mediation structural equation model (SEM). First, the overall goodness-of-fit for this structural model was assessed against the established criteria from our CFA (Table 7). Upon confirming an acceptable model fit, we proceeded to test the specific indirect pathways. The significance of the mediating effects of both positive and negative emotion was examined, and a formal pairwise comparison was conducted to determine if a statistically significant difference existed between the two pathways (Table 8).

3. RESULT

3.1. Preliminary Analyses

To establish the structural validity of our measurement instruments, we performed a series of Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) in AMOs on the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF), the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), and the Executive Functioning Scale (EFS). As presented in Table 2, the results revealed that all three measurement models demonstrated a good fit to the data, meeting the established criteria (Table 1). The fit indices for the CTQ-SF (CMIN/DF = 1.905, CFI = .974, TLI = .972, RMSEA = .036, RMR = .038), the PANAS (CMIN/DF = 2.772, CFI = .965, TLI = .961, RMSEA = .051, RMR = .030), and the EFS (CMIN/DF = 1.447, CFI = .976, TLI = .975, RMSEA = .026, RMR = .047) were all satisfactory. These findings support the structural validity of the scales, confirming their suitability for the subsequent structural equation modeling.

3.2. Descriptive Statistics

The final sample for analysis comprised 683 adolescents, following the exclusion of invalid questionnaires and data that failed to meet statistical criteria. To characterize the sample, we first examined its sociodemographic profile. As detailed in Table 3, the sample was nearly evenly distributed by gender (49% male; 51% female) and included both middle (12–14 years; 47%) and late (15–17 years; 53%) adolescents. Most parents held a bachelor’s degree or lower, and a majority of families (70%) reported an annual income in the 25M–40M range. Descriptive statistics for the primary study variables (presented in Tables 4 and 5) indicated that participants reported significant levels of abuse and neglect, coupled with lower positive and higher negative emotions. Concurrently, their scores for core executive functioning components and overall performance fell within the moderate to high range.

To quantify the prevalence of specific Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and examine potential gender differences, we analyzed the incidence rates for each category. As detailed in Table 4, our analysis revealed that several forms of adversity were highly prevalent in the sample. Notably, emotional neglect (reported by 37% of males and 38% of females), physical abuse (37% M, 32% F), and emotional abuse (33% M, 31% F) were among the most commonly endorsed experiences. Similarly, key indicators of household dysfunction, including witnessing a mother being treated violently and household substance abuse, were reported by approximately one-third of participants. Conversely, sexual abuse and having an incarcerated household member were the least frequent experiences. These findings underscore the widespread nature of childhood adversity—particularly maltreatment and household dysfunction—within this adolescent sample, reinforcing the imperative to investigate its developmental consequences.

To establish a quantitative profile of our sample, we computed descriptive statistics for all primary research variables. As presented in Table 5, the data indicated notable levels of adversity, with mean scores for emotional abuse (M=18.56, SD=4.84) and physical abuse (M=18.61, SD=4.70) being particularly prominent. A key finding emerged in the domain of emotional states, where the mean scores for positive emotion (M=26.77, SD=8.42) and negative emotion (M=26.82, SD=7.83) were nearly identical. Furthermore, participants reported moderate-to-high levels of executive functioning, with mean scores for all six core components consistently above 3.70 and an overall EF score of 196.39 (SD=41.15). These descriptive statistics provide the empirical foundation for our subsequent correlational and mediation analyses.

3.3. Correlation

To establish the bivariate relationships among our core variables, we performed a Pearson correlation analysis. As detailed in Table 6, the analysis revealed a consistent pattern of significant associations. All five types of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) were negatively correlated with positive emotion and executive functioning (EF), and positively correlated with negative emotion. Furthermore, EF was positively associated with positive emotion (r = .492) and negatively associated with negative emotion (r = -.573). Crucially, all reported correlations remained highly significant (p < .01) even after a conservative Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. These results provide strong preliminary evidence for our proposed theoretical model and confirm that the necessary preconditions for testing mediation have been met.

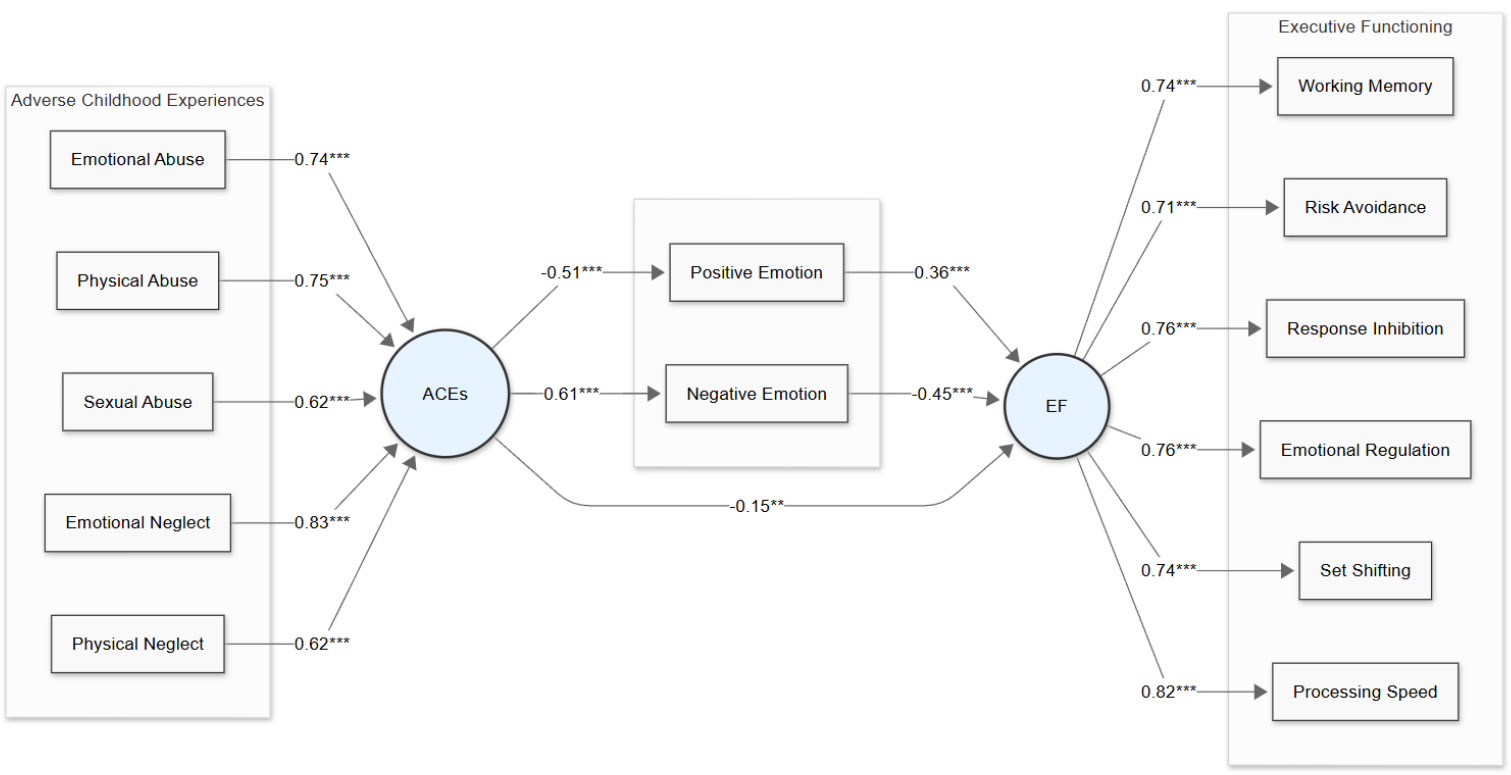

3.4. Model Fit Index

To test the overall fit of our hypothesized model, we performed a structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis in AMOS. As detailed in Table 8, the model demonstrated a good fit to the data, with all key indices meeting or exceeding recommended thresholds (CMIN/DF = 2.936, CFI = .967, TLI = .959, RMSEA = .053). The final model with standardized path coefficients is presented in Fig. (1). All specified paths were statistically significant. Specifically, Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) were strongly associated with lower positive emotion (β = -.51) and higher negative emotion (β = .61). In turn, positive emotion was a significant positive predictor of executive functioning (EF) (β = .36), whereas negative emotion was a stronger negative predictor (β = -.45). Importantly, a significant direct path from ACEs to EF remained even after accounting for the mediators (β = -.15). Collectively, these findings provide robust support for our proposed mediation model, illustrating the distinct pathways through which childhood adversity impacts executive functioning.

3.5. Main Hypothesis Testing: The Mediation Model

To test our central hypotheses, we constructed a parallel mediation model using AMOS and employed a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples to estimate the indirect effects. As detailed in Table 7, the analysis revealed a significant indirect effect of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) on executive functioning (EF) through positive emotion (β = -.038, 95% CI [-.049, -.029]). A significant indirect effect was also found through negative emotion (β = -.057, 95% CI [-.072, -.045]). Crucially, a direct comparison of these pathways indicated that the mediating effect of negative emotion was significantly stronger than that of positive emotion (Difference Estimate = .019, 95% CI [.005, .034]). These results support our mediation hypotheses and demonstrate that negative emotion serves as a more potent mediator in the link between childhood adversity and executive functioning deficits.

4. DISCUSSION

This study examined the mediating roles of positive and negative emotional states in the relationship between adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and executive functioning (EF) among Chinese adolescents. Our findings robustly supported the hypothesized model: a higher cumulative ACE score was significantly associated with poorer EF. As predicted, both positive and negative emotions were significant and independent mediators of this association. Critically, our results revealed a pronounced asymmetry in their influence. The indirect pathway from ACEs to EF through negative emotion was significantly stronger than the pathway through positive emotion, indicating that negative affect is the primary mechanism driving EF deficits following childhood adversity. A significant direct effect of ACEs on EF also persisted, suggesting that other unmeasured pathways contribute to this deleterious link.

These findings carry substantial theoretical and practical weight. Theoretically, they offer a crucial psychological specification to the prevailing “toxic stress” model [45]. While this framework adeptly explains the neurobiological sequelae of ACEs, our study elucidates a measurable psychological mechanism—affective dysregulation—that translates early stress into downstream cognitive impairment [30].

The final structural equation model of aces, emotional states, and executive functioning.

The novel contribution lies in the empirical demonstration that negative emotion is not merely a mediator but a significantly more potent one than the deficit in positive emotion, thus providing a more granular understanding of the ACEs-EF pathway. Practically, this has direct and actionable implications for intervention. It strongly suggests that while fostering positive affect is undoubtedly beneficial, clinical and educational programs must prioritize strategies that directly target the mitigation and regulation of negative emotions [46]. Evidence-based, school- and family-centered interventions [47, 48] emphasizing cognitive-behavioral techniques [49], mindfulness [7], and explicit emotion regulation training represent the most promising avenues for buffering adolescents against the cognitive toll of ACEs [50]. Identifying negative emotion as the principal driver allows for more efficient allocation of therapeutic resources.

Our results are broadly consistent with the international literature, which shows that childhood adversity disrupts emotional development, predicting executive dysfunction [51]. The observed negative association between ACEs and positive affect, and the positive association between ACEs and negative affect, corroborate foundational work on the emotional consequences of trauma [52]. Our study advances this literature in two vital ways. First, unlike research that has often conflated emotional states or focused solely on negative affect [53], our use of a parallel mediation model allowed us to disentangle and directly compare the relative strength of the two emotional pathways. The finding that negative emotion is the dominant pathway is a novel insight that prior research designs could not reveal. Second, by grounding our investigation in a large, non-Western sample, we begin to address the field’s over-reliance on WEIRD populations [54]. The consistency of the core findings suggests these mechanisms may be largely universal. However, the high prevalence of emotional neglect in our Chinese sample, coupled with the descriptive parity in positive and negative emotion scores, underscores the importance of considering how cultural norms surrounding emotional expression may shape both the experience and reporting of adversity’s impact.

A central question arising from our findings is why negative emotionss are a more powerful mediator than positive emotions. We propose a mechanism rooted in an attention and resource allocation framework. Chronic exposure to ACEs can induce a state of hypervigilance and threat sensitivity, fostering persistent negative affective states like rumination, worry, and anxiety [55]. These states are cognitively expensive; they actively “hijack” the limited-capacity cognitive resources—particularly working memory and attentional control—that are indispensable for effective executive functioning [56]. From this perspective, negative emotion functions as an active, ongoing drain on the cognitive system [57]. In contrast, a deficiency in positive emotion may represent a more passive deficit [58]. While the absence of positive affect can diminish motivation, curiosity, and cognitive flexibility, it may not actively consume cognitive resources in the same parasitic manner. It is therefore plausible that the superior mediating strength of negative emotion stems from its role as an active disruptor of the cognitive architecture supporting EF.

5. LIMITATIONS

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations. First, its cross-sectional design precludes definitive causal inference [59]. Although our model is theoretically grounded, only longitudinal research can firmly establish the temporal ordering of ACEs, affective dysregulation, and EF deficits. Second, our exclusive reliance on self-report measures introduces potential shared method variance and susceptibility to recall and social desirability biases [60]. Future work would be strengthened by incorporating multi-informant data (e.g., parent, teacher) and objective, performance-based EF tasks. Third, while the focus on a Chinese sample is a key strength, it also circumscribes the generalizability of our findings to other cultural contexts [61]. Finally, our use of a standard ACEs checklist did not capture the nuanced dimensions of trauma, such as the timing, duration, or subjective severity of each experience, which could moderate the observed relationships.

6. FUTURE DIRECTIONS

This study’s limitations illuminate clear avenues for future research. A longitudinal design tracking Chinese adolescents is the critical next step to empirically validate the proposed causal chain. Such studies would enable the examination of developmental trajectories and identify sensitive periods for intervention. Future research should also adopt a multi-method approach, integrating self-report data with performance-based EF assessments (e.g., n-back, flanker tasks) and physiological indicators of emotional regulation (e.g., heart rate variability) for a more robust and objective analysis. Cross-cultural comparative studies are also essential to test whether the dominance of negative emotion as a mediator is a universal phenomenon or one that is culturally moderated. Finally, future models could incorporate other potential psychological mediators (e.g., coping strategies, social support) and test for moderators (e.g., genetic predispositions, peer relationship quality) to build a more comprehensive model of risk and resilience.

CONCLUSION

In sum, this study provides compelling evidence that emotional states are a critical conduit through which childhood adversity impairs executive functioning in Chinese adolescents. Its primary contribution is the empirical demonstration that negative emotion functions as a significantly more potent mediator than the mere absence of positive emotion. This finding clarifies a primary pathway of risk, providing a clear and urgent mandate for interventions: to shield adolescent cognition from the lasting impact of trauma, we must prioritize teaching the skills to effectively manage and regulate negative affect.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: M.S.A.: Study conception and design; H.Y.: Conceptualization. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| ACEs | = Adverse Childhood Experiences |

| EF | = Executive Function(ing) |

| SPSS | = Statistical Product and Service Solutions |

| Amos | = Analysis of moment structures |

| PE | = Positive Emotion |

| NE | = Negative Emotion |

| ACE-Q | = Adverse Childhood Experiences Questionnaire |

| CTQ-SF | = Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form |

| PANAS | = Positive And Negative Affect Sclae |

| EFS | = Executive Functioning Scale |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved by the research committee of the Faculty of Education, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Malaysia (Ethic Approval No: KPM.600-3/2/3-eras(17140)).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article will be available from the corresponding author [M.S.A] upon reasonable request.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.