All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Meaning in a Purposeless Cosmos: An Interdisciplinary Integrative Review of Philosophy, Psychology, and Science

Abstract

Background

In an era of scientific uncertainty and philosophical skepticism, the question of life’s meaning has renewed psychological and cultural importance. Although the cosmos lacks intrinsic purpose, humans continue to seek and sustain meaning amid existential ambiguity. This integrative review examines whether durable frameworks of meaning can be developed without cosmic teleology.

Methods

Using an integrative conceptual review, this study synthesizes insights from existential philosophy and meaning-centered psychology with recent developments in cosmology. Core sources include Sartre and Frankl, therapeutic models, such as Logotherapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), and scientific perspectives from multiverse theory and contemporary cosmological narratives. This study proposes a four-phase model of existential meaning-making embedded in a recursive adaptive process.

Results

The model comprises four interrelated components: (1) value-driven goal setting, (2) reflective self-awareness, (3) purposeful engagement, and (4) responsible decision-making operating within cycles of disruption, integration, and renewal that cultivate resilience and existential growth.

Discussion

While the universe may be purposeless, reflective consciousness, ethical deliberation, and intentional action enable subjective meaning. Bridging existential philosophy with clinical practice and cosmology, the model highlights meaning-making across suffering, uncertainty, and scientific disenchantment.

Conclusion

Even in a purposeless cosmos, individuals can construct meaningful lives through value-oriented consciousness and ethical engagement. The model offers a transdisciplinary foundation for therapeutic work, philosophical reflection, and education, and invites empirical validation and implementation.

1. INTRODUCTION

The contemporary world, shaped by rapid scientific progress and sociocultural transformation, increasingly forces individuals to confront foundational questions about the meaning and purpose of existence. Developments in cosmology, such as the multiverse hypothesis and quantum indeterminacy, depict a universe governed by randomness and devoid of intrinsic purpose [1]. This cosmological view challenges traditional metaphysical beliefs and raises urgent questions about whether meaning is something to be discovered or something that must be consciously created.

In parallel, modern psychological research highlights the central role of meaning in mental health, particularly in the face of existential anxiety and identity loss [2-4]. The decline of traditional belief systems and the fragmentation of cultural narratives have left many individuals navigating a world perceived as meaningless, resulting in heightened psychological vulnerability [5].

This study investigates whether a coherent and enduring sense of meaning can be constructed in a universe that appears cosmically indifferent. By integrating existential philosophy (e.g., Sartre), meaning-centered psychology (e.g., Frankl, Wong), and insights from contemporary cosmology (e.g., Carroll, Tegmark), the research aims to develop a conceptual framework for meaning-making. In doing so, it evaluates the potential for a dynamic, interdisciplinary model that addresses both philosophical depth and psychological applicability in the modern search for meaning.

The search for meaning in life, particularly in a universe seemingly devoid of inherent purpose, has become a focal issue across existential philosophy, meaning-centered psychology, and modern cosmology. This section outlines the theoretical foundations underpinning this research, highlighting how these disciplines inform an integrated understanding of meaning-making.

1.1. Existential Philosophy: Freedom, Responsibility, and Meaning Construction

Existentialist thought, especially as articulated by Jean-Paul Sartre, asserts that “existence precedes essence,” that humans are not born with a predefined purpose but must create their own meaning through free and responsible choices [6]. Sartre posits that individuals are “condemned to be free,” meaning they cannot escape the responsibility of choice even in a meaningless cosmos. This view emphasizes that in the face of existential crises, such as failure, alienation, or mortality, individuals must actively construct meaning rather than passively await it [7].

Albert Camus (1942) similarly addresses the “absurd,” the dissonance between the human desire for meaning and the silent universe, concluding that rebellion through meaning-creation is the only authentic response. Existentialists do not deny the lack of cosmic meaning but affirm the necessity of personal, subjective meaning-making.

1.2. Psychology of Meaning: Logotherapy and the Will to Meaning

From a psychological standpoint, Viktor Frankl's logotherapy argues that the primary human drive is not pleasure (Freud) or power (Adler), but meaning [2]. Based on his experiences in Nazi concentration camps, Frankl found that even under extreme suffering, individuals could survive and grow psychologically by discovering meaning in their suffering.

Frankl identifies three principal sources of meaning: (1) creative endeavors, (2) experiences of love or nature, and (3) the attitude one adopts toward unavoidable suffering. These ideas were further expanded by Paul Wong, who developed the concept of “meaning-centered therapy,” focusing on integrating meaning, purpose, and personal values as protective factors against existential anxiety [8].

Contemporary studies have shown that individuals who perceive their lives as meaningful demonstrate greater psychological resilience, lower anxiety, and improved well-being [9].

1.3. Modern Cosmology: Cosmic Indifference and Human Meaning-making

Modern cosmology, through theories, such as the multiverse hypothesis and quantum indeterminacy, presents a view of the universe that is impersonal and devoid of teleological purpose. According to Tegmark (2008) [28], and Carroll (2016) [1], the multiverse framework implies that our universe may be just one of countless others, each governed by different physical laws. Such models challenge traditional metaphysical assumptions about human centrality or divine intention.

Additionally, quantum mechanics, particularly the indeterminacy principle, undermines deterministic views of reality and suggests fundamental unpredictability at the micro level [10, 11]. These scientific models reinforce a vision of the cosmos as neutral or indifferent, prompting philosophical and psychological responses rather than offering inherent answers.

In light of this, some theorists argue that the absence of intrinsic cosmic meaning compels human beings to construct meaning subjectively, through culture, relationships, art, and moral commitments [12].

1.4. Synthesis: Toward an Integrated Framework

Bringing these disciplines together, it has been observed that a convergence around the idea that while the universe may not provide inherent meaning, individuals can create meaning through conscious engagement with their values, choices, and experiences. This interdisciplinary synthesis reinforces the idea that meaning-making is not merely a psychological coping mechanism but a necessary existential project in the face of a disenchanted world.

1.5. Literature Review

1.5.1. Nihilism and Existentialism: The Crisis of Meaning in the Modern World

Nihilism and existentialism, as articulated by Nietzsche and Sartre, provide foundational perspectives for understanding the modern crisis of meaning and the absurdity of human existence. Although these philosophies approach the issue of meaning from different angles, they converge on the view that humanity faces a profound existential void in a world lacking inherent purpose. Nietzsche’s concept of nihilism centers on the “death of God” and the subsequent collapse of metaphysical values that once anchored human life [13]. Without these external sources of meaning, individuals are confronted with a choice: passively accept meaninglessness or actively create new values. Existentialist philosophers, such as Sartre, emphasize the latter path by highlighting the role of individual freedom and responsibility in meaning-making [14]. Sartre’s notion of “nothingness” underscores that human beings, as conscious agents, must take ownership of their freedom and construct personal meaning. Similarly, Camus, in The Myth of Sisyphus, interprets the confrontation with absurdity as a struggle that must be embraced rather than denied. For Camus, the acceptance of absurdity is itself a form of freedom that enables the creation of meaning despite the indifference of the universe [15].

1.5.2. Contemporary Philosophy on the Meaning of Life

Building on existential and nihilistic foundations, contemporary philosophers have expanded the discourse on meaning by incorporating insights from analytic philosophy, ethics, and psychology. Wolf (2010) [16], introduces a hybrid model in which meaningfulness arises from the intersection of subjective attraction and objective value. She contends that a life is meaningful only when one’s engagements are both personally fulfilling and objectively worthwhile [16]. For example, while collecting rare stones may provide personal satisfaction, it lacks broader societal or moral significance. In contrast, dedicating oneself to humanitarian efforts satisfies both criteria of meaningfulness.

Metz (2013) advances a naturalistic account of meaning, identifying sources, such as social relationships, creativity, and moral commitments, without appealing to supernatural assumptions. He argues that these elements contribute to human flourishing and ethical living [17]. Similarly, Seachris (2020) stresses the importance of normative frameworks in defining meaning, asserting that meaningful lives must adhere to evaluative standards that allow for positive or negative assessments [18]. Jennifer Frey (2014) also emphasizes the social embeddedness of meaning, arguing that it arises through engagement with valuable social and ethical projects [19].

Todd (2017) offers a pragmatic critique of metaphysical realism by framing meaning as a cultural and interpretive construction, shaped by individual and collective narratives but bounded by objective reality [20]. From a cognitive science perspective, Dennett (1995, 2013) conceptualizes meaning as an adaptive biological mechanism evolved to enhance human survival and flourishing [21, 22]. Skinner (2002) highlights the significance of social roles and historical context in shaping meaning, linking individual purpose to societal commitments [23]. Complementing these philosophical views, psychological research demonstrates the role of meaning in mental health. For example, Trothen (2019) shows that a sense of meaning contributes to resilience and psychological well-being, enabling individuals to manage life crises more effectively [24].

1.5.3. The Concept of Meaning: Discovery or Creation?

The question of whether meaning is discovered or created remains central to philosophical debate. While nihilism and existentialism emphasize the absence of inherent meaning and the necessity of its creation, other thinkers, notably Viktor Frankl and Søren Kierkegaard, focus on the active construction of meaning through individual choice and faith. Frankl’s experiences in Nazi concentration camps led him to argue that even under extreme suffering, individuals can find or create meaning that sustains life and resilience [2]. Similarly, Kierkegaard (1849) stresses the importance of responsible personal choice and faith in confronting absurdity, thereby enabling the creation of meaning in an otherwise meaningless world [25].

1.5.4. Integrated Conclusion: Nihilism and Existentialism as Two Sides of the Same Coin

Despite their apparent differences, nihilism and existentialism can be understood as complementary responses to the modern crisis of meaning. Nihilism underscores the absence of any predetermined purpose, whereas existentialism emphasizes human freedom to construct meaning. Taken together, both philosophies affirm the individual’s responsibility to create value and purpose within a universe that appears devoid of inherent meaning.

1.5.5. Contemporary Philosophical Perspectives on Meaning: An Integrated View

Recent philosophical scholarship has enriched the discourse on meaning by integrating analytic rigor with ethical considerations and psychological insights. In this view, meaning emerges from the dynamic interplay between subjective engagement and objective value, individual freedom, and social embeddedness. This synthesis highlights that the crisis of meaning is simultaneously a philosophical and existential challenge, encompassing personal agency, normative structures, and broader social realities. As existentialist thought suggests, the nihilistic void is not merely an absence but also an opportunity for meaning creation, one that fosters resilience, purpose, and well-being.

1.6. Problem Statement

Despite extensive philosophical and psychological inquiry into the meaning of life, a clear interdisciplinary framework that integrates existential philosophy, contemporary scientific theories (such as multiverse cosmology), and psychological approaches to meaning-making remains underdeveloped. Classical existentialism and nihilism address the crisis of meaning at a conceptual level but often lack practical applicability for addressing modern psychological and social challenges related to meaninglessness [2, 26]. Conversely, psychological studies emphasize the benefits of meaning for mental health and resilience but frequently fail to incorporate deeper philosophical and cosmological insights that shape individuals’ existential contexts [26]. Furthermore, recent developments in cosmology, such as multiverse theory, introduce new dimensions to the discussion of meaning by challenging traditional notions of purpose grounded in a singular, ordered universe [1, 27].

This fragmentation across disciplines results in a gap that limits our understanding of how individuals can effectively discover or create meaning within the increasingly complex realities of contemporary life. Therefore, there is a pressing need for an integrated, interdisciplinary theoretical framework that bridges philosophy, psychology, and scientific cosmology to better explain and support meaning-making processes in modern contexts.

1.7. Research Objectives / Questions

This study aims to address the identified gap by pursuing the following objectives:

- To critically examine and synthesize philosophical, psychological, and cosmological perspectives on the meaning of life.

- To evaluate the implications of multiverse theories and existential philosophy for contemporary experiences of meaning and meaninglessness.

- To propose an integrated theoretical framework that supports the process of meaning creation and discovery in individuals facing existential and psychological challenges.

Accordingly, the main research questions guiding this study are:

- How do contemporary philosophical theories, including nihilism and existentialism, conceptualize the crisis of meaning in light of modern scientific developments?

- What role do psychological factors and mental health considerations play in the experience and creation of meaning?

- How can insights from cosmology, particularly multiverse theories, inform and reshape our understanding of life’s meaning?

- Is it possible to develop a comprehensive interdisciplinary framework that facilitates meaning-making in a world that appears inherently purposeless?

2. METHODOLOGY

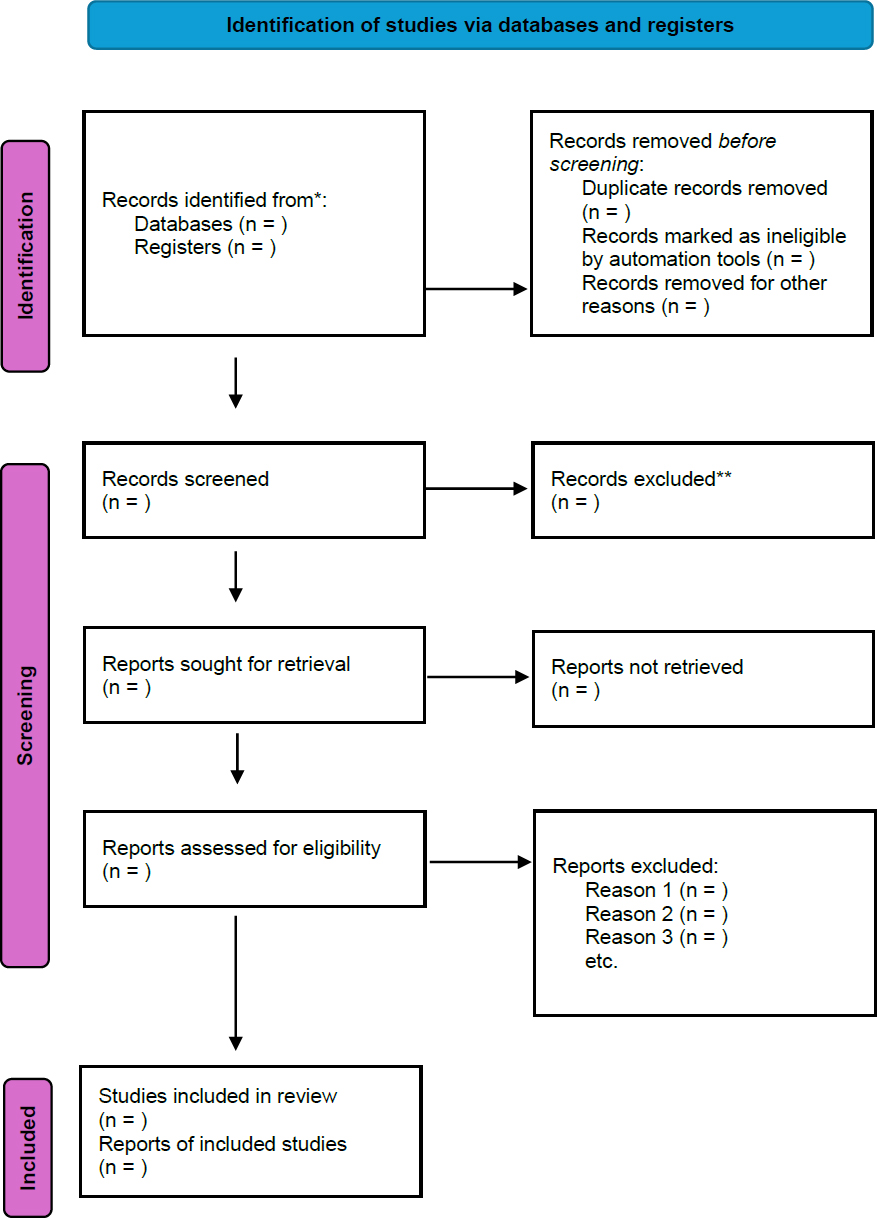

Although this study is based on an integrative conceptual review, the PRISMA framework was followed to ensure transparency in the literature search process. The methodology consisted of the following steps:

- Literature Search: A comprehensive search was conducted in academic databases, including Google Scholar, JSTOR, and ResearchGate, focusing on peer-reviewed articles, books, and reputable sources published within the last three decades. Keywords included “meaning of life,” “existentialism,” “nihilism,” “psychology of meaning,” and “multiverse theory.”

- Inclusion Criteria: Studies were selected according to their relevance to the conceptualization of meaning, their interdisciplinary approach, and their contribution to understanding existential and psychological dimensions of meaning.

- Data Extraction and Analysis: Key themes and theoretical constructs were identified and categorized within the philosophical, psychological, and scientific domains. A thematic synthesis was employed to integrate perspectives and highlight overlaps as well as gaps.

- Framework Development: Based on the synthesized literature, an integrated theoretical framework was developed to address the research questions and support practical applications of meaning-making in contemporary contexts.

This qualitative integrative review methodology is appropriate given the study’s aim to bridge multiple disciplines and to develop a novel conceptual framework rather than to test specific hypotheses through empirical data collection.

The study selection process followed PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Fig. 1). A comprehensive search was performed across three major databases: PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science. A total of 723 records were initially identified. After removing 154 duplicates, 569 unique records remained for screening. Titles and abstracts were reviewed, and 412 records were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. The full texts of the remaining 157 articles were then assessed for eligibility. Based on predefined criteria, 34 studies were ultimately deemed eligible and included in the final synthesis.

3. RESULT

This article investigates the complex issue of meaning in life by synthesizing perspectives from existential philosophy and the psychology of meaning. The findings highlight several key points:

PRISMA flowchart.

3.1. Existential Meaninglessness and Individual Responsibility

Existential philosophy, particularly Sartre's notion that “existence precedes essence,” posits that the world itself lacks inherent meaning. Consequently, meaning is not discovered but must be created by the individual through free choices and reflective self-awareness [28]. This view underscores the central role of personal responsibility in constructing one’s life purpose, even in the face of existential crises [29].

3.2. Psychological Processes of Meaning-making

Complementing the philosophical perspective, psychological theories, most notably Viktor Frankl's logotherapy, demonstrate that meaning can be actively created, especially in contexts of suffering and adversity [30]. Psychological interventions, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), further support individuals in coping with existential challenges by fostering acceptance and deliberate engagement in meaning-making [11].

3.3. Integration of Philosophy and Psychology

The combination of existential philosophy and the psychology of meaning provides a comprehensive framework for addressing crises of meaning. This integration offers practical benefits, including enhanced psychological well-being, empowerment, and resilience. Encouraging individuals to acknowledge their freedom and responsibility enables the creation of meaning across diverse domains of life.

3.4. Dynamic and Recursive Model of Meaning-making

The proposed mathematical model conceptualizes meaning as a dynamic, nonlinear, and recursive process that evolves through existential crises (Et), coping (Ct), personal growth (Gt), meaning construction (Mt), and psychological well-being (Pt). The model highlights recursive feedback loops, showing how growth and meaning continuously influence coping strategies over time, thereby reflecting the ongoing and adaptive nature of human meaning-making [31].

3.5. Application to Real-Life Crises

Using the example of coping with loss, the model illustrates how initial existential disruption reduces perceived meaning. However, through active coping and subsequent growth, individuals are able to reconstruct meaning and enhance well-being. This recursive process strengthens resilience and equips individuals to face future challenges more effectively.

3.5.1. Limitations and Future Directions

Although existential and psychological models provide powerful insights, they may not fully resolve all human struggles with meaning and mental health. Further interdisciplinary research, particularly incorporating developments in cosmology and artificial intelligence, is recommended to expand and potentially transform the understanding of meaning.

3.5.2. Implications for Human Life in a Modern Context

The concept of meaning is not static but is continuously created and re-created within the context of an inherently purposeless world. This ongoing search for meaning is fundamental to human existence, supporting both coping with existential emptiness and maintaining psychological health. By integrating philosophy, psychology, and science, new pathways emerge for inquiry and personal growth, as summarized in Table 1.

4. DISCUSSION

This study examined the problem of meaning in life through an interdisciplinary lens that combined existential philosophy with psychological theory. Drawing on the works of Sartre, Frankl, Yalom, and contemporary theorists, such as Paul Wong, the findings suggest that although life may lack inherent meaning, individuals can construct meaningful lives through conscious choice, personal responsibility, and psychological adaptation. Importantly, the “creating meaning” model introduced in this study reframes meaning not as something to be discovered externally, but as a recursive, self-generated process that evolves through one’s ongoing responses to existential crises [32].

| Influence/Relation | Description | Variable |

|---|---|---|

| Positively influences coping (Ct) | Triggering event challenging personal meaning | Existential crisis (Et) |

| Mediates between crisis and growth | Psychological response to crisis | Coping (Ct) |

| Enhances meaning (Mt) and feeds back to coping (Ct) | Personal development after coping | Growth (Gt) |

| Positively influences well-being (Pt) and coping (Ct) | Sense of life meaning is constructed by the individual | Meaning (Mt) |

| Outcome of meaning (Mt) and growth (Gt) | Psychological health and life satisfaction | Well-being (Pt) |

4.1. Psychological Perspectives: The Crisis of Meaning and the Process of Meaning-making

In psychology, the exploration of meaning, particularly in the aftermath of catastrophic experiences and existential crises, has received significant attention. Viktor Frankl, through the development of logotherapy, emphasizes that the meaning of life does not vanish in times of crisis; rather, it can become a powerful driving force when individuals confront suffering and major challenges. Drawing on his harrowing experiences in Nazi concentration camps, Frankl demonstrated that even in the darkest circumstances, human beings can find meaning that sustains life. According to him, individuals should confront crises by identifying personal sources of meaning, which in turn enables them to cope with psychological stress and emotional hardship [2].

Paul Wong extends this perspective by emphasizing meaning as not only an individual phenomenon but also a key factor in maintaining mental health and resilience. He argues that individuals face meaning-related challenges throughout life, and the process of meaning-making enables them to navigate such crises. Meaning-making, therefore, represents a crucial psychological process through which individuals can transform crises into opportunities for growth, grounded in personal experiences and beliefs [4]. Importantly, Wong highlights that meaning is shaped not only at the individual level but also through interactions with the social and cultural environment. Consequently, one’s relationships with others and engagement with the broader world significantly influence the meaning-making process.

Irvin Yalom, working within existential psychology and psychotherapy, underscores that existential concerns, such as death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness are inevitable aspects of the human condition. According to Yalom, an individual’s ability to confront these challenges and to discover or create meaning within them is central to maintaining psychological health. In this view, existential crises should not be avoided but rather embraced as opportunities for searching for and constructing new meaning [5].

Martin Seligman, in the context of positive psychology, identifies meaning as a fundamental factor in psychological well-being and happiness. Within his PERMA model of well-being, “meaning” is one of the five central components, alongside positive relationships, accomplishment, engagement, and positive emotions. This model emphasizes that meaning not only contributes to life satisfaction but also plays a vital role in reducing stress and enhancing motivation for life [32].

Meaning-making models developed by scholars, such as Crystal Park and Roy Baumeister provide important insights into how the process of meaning-making operates and how it affects psychological well-being. Park emphasizes that when individuals confront meaning-related crises, the process of meaning-making enables them to transform these crises into opportunities for growth and development. In this view, the meaning of life is dynamic and evolving, continuously reshaping itself across the lifespan and supporting individuals in adapting to life’s changes and challenges.

Roy Baumeister [33], in his research, concluded that meaning in life influences not only psychological outcomes but also physiological functioning. Specifically, he argues that individuals who lack a sense of meaning or purpose are less capable of coping with difficulties and stress, and this absence of meaning increases vulnerability to depression and anxiety. Baumeister, therefore, underscores the crucial role of meaning as a catalyst for both psychological resilience and physiological well-being.

4.2. Multiverse Theories and their Impact on the Crisis of Meaning in Life

Multiverse theories, advanced by physicists, such as Max Tegmark [35], introduce the profound concept of parallel and potentially countless universes, which can significantly reshape the understanding of the cosmos and humanity’s place within it. According to these theories, our universe may be only one among an infinite number of possible universes, each governed by different physical laws. Tegmark, in particular, developed the “Mathematical Multiverse” hypothesis, which suggests that the laws of physics and mathematics may differ fundamentally across universes [34]. For many individuals, such perspectives can evoke profound feelings of meaninglessness and purposelessness.

If the universe has arisen randomly without any underlying design, humans may conclude that their lives also lack inherent purpose. This perspective, depicting a random and purposeless cosmos, can exacerbate existential crises. Even if multiverse theories offer no direct implications for human life, they nonetheless raise challenges for the human search for purpose and meaning.

Alongside these cosmological perspectives, quantum uncertainty, first articulated by Werner Heisenberg in 1927, has also influenced human conceptions of meaning [11]. At the subatomic level, nothing is certain; everything is probabilistic. This scientific indeterminacy often shapes existential reflection, reinforcing the perception that life itself is uncertain. Psychologically, such uncertainty can foster experiences of helplessness and meaninglessness, as individuals may come to view life as a series of unpredictable and aimless events.

Cosmic evolution without design, as discussed by Sean Carroll [1] and Stephen Jay Gould [34], further reinforces this worldview. Both argue that the universe and human life did not emerge through purposeful design but through random evolutionary and natural processes. Carroll specifically maintains that cosmic evolution has no ultimate goal but consists of natural events that, through chance, led to the emergence of life [1]. Similarly, Gould highlights that biological evolution and natural selection, rather than preordained planning, explain the rise of life [34]. These perspectives stand in sharp contrast to religious and teleological views, suggesting instead that life and the cosmos are the outcomes of purposeless processes. Such views can intensify feelings of existential meaninglessness [35].

In response, psychologists and philosophers have proposed meaning-centered approaches to counterbalance the sense of purposelessness suggested by modern science. Viktor Frankl [29], in Man’s Search for Meaning, emphasizes that meaning can be found in any circumstance, even the most extreme crises. According to Frankl, individuals are capable of creating meaning through personal goals, values, and small everyday choices. Similarly, Wong [3] highlights meaning-making as a process through which individuals construct purpose and resilience, even when external structures appear absent.

Taken together, multiverse theories, quantum uncertainty, and cosmic evolution without design suggest that the universe may lack inherent purpose. These perspectives profoundly impact existential reflection and the crisis of meaning. Yet, existential and psychological approaches emphasize that even in a purposeless cosmos, human beings possess the capacity to create and sustain meaning in their lives through choice, resilience, and intentional meaning-making.

Thus, the convergence of scientific and philosophical perspectives can both intensify the crisis of meaning and illuminate possible pathways for constructing it. Life, therefore, may be understood as an ongoing process of creating personal meaning, one that originates within the individual and is continuously shaped through choice, reflection, and engagement with the world.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Philosophical, Scientific, and Psychological Perspectives on the Meaning of Life

A comparative analysis of philosophical, scientific, and psychological perspectives on the meaning of life highlights both profound contradictions and important points of overlap. Scientific theories, such as multiverse cosmology (Tegmark) and cosmic evolution without design [36, 37] portray the universe as a random system devoid of inherent purpose or teleology. In contrast, existentialist thinkers [38, 39] and meaning-oriented approaches, such as Frankl’s logotherapy and Wong’s meaning-centered psychology emphasize that individuals bear responsibility for creating their own meaning, thereby achieving purpose in an otherwise indifferent world. Here lies the fundamental contradiction: whereas scientific theories describe the cosmos as purposeless, philosophical and psychological theories underscore human agency in meaning creation. Gadamer [39] observes that while these perspectives appear contradictory, they may also converge, as human beings interpret and inhabit reality in diverse ways.

Existentialist theories, particularly those of Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus, argue that the world itself is meaningless. Yet this very meaninglessness can be appropriated as a basis for authentic existence. Sartre insists that humans are radically free and therefore responsible for constructing their lives [39]. Camus, in The Myth of Sisyphus, suggests that confronting absurdity can lead either to despair or to a liberating recognition of freedom [38]. Similarly, Franz Kafka’s literary vision interprets meaninglessness as an opportunity for a more genuine human journey, albeit one fraught with ambiguity and tension.

Psychological perspectives approach meaning from a different angle, treating it less as a metaphysical truth and more as a psychological necessity. Frankl, in Man’s Search for Meaning [30], argues that meaning is essential for enduring suffering and sustaining life. For him, individuals must discover or construct meaning in direct relation to how they confront crises. This stands in contrast to metaphysical approaches that seek universal or eternal purpose. Wong [3] and Yalom [26] also conceptualize meaning primarily as a psychological process. In their view, humans are constantly searching for meaning, but this meaning is essentially individual, emerging from personal experiences, relationships, and existential choices.

The question of whether the recognition of meaninglessness ultimately liberates humans or drives them toward nihilism remains central in both philosophy and psychology. Sartre [38] interprets meaninglessness as the foundation of radical freedom, placing responsibility squarely on individuals to define their lives. This freedom, however, can also engender feelings of emptiness. Camus [37] warns that awareness of life’s absurdity can lead to despair and depression, yet he insists that acceptance of the absurd can foster a form of freedom, one that releases individuals from external constraints and motivates them to live authentically.

On the other hand, psychological theories, such as those of Irvin Yalom and Paul Wong [3, 26], suggest that the experience of meaninglessness can produce anxiety and identity crises, yet it also opens the possibility of discovering meaning from within. In this perspective, the meaning of life is not located in the external world but emerges through personal experience and psychological processes.

Irvin Yalom, within the framework of existential psychotherapy, emphasizes that existential crises are unavoidable aspects of human existence. Concerns, such as death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness, are intrinsic to human life [5]. According to Yalom, individuals have two primary responses to these crises: they may flee from them through denial, or they may confront them as opportunities to search for meaning. For Yalom, finding meaning in such crises is essential not only for alleviating anxiety and psychological distress but also for cultivating a deeper understanding of the self and the world. This process is particularly important for maintaining mental health and achieving life satisfaction and fulfillment [5].

One of the most significant existential crises Yalom addresses is death. As an inescapable reality, death often provokes profound anxiety, especially during moments of crisis or aging. Yet Yalom argues that the fear of death can be transformed into an opportunity to clarify values and priorities [5]. For example, an individual facing their own mortality may reflect on how they wish to live their remaining time, the legacy they hope to leave, and the values most central to them. In this process, life acquires renewed significance. By accepting death as inevitable rather than fleeing from it, individuals may gain a conscious perspective on life, making every moment an opportunity for experience and growth. A patient awaiting serious surgery, for instance, may begin contemplating death and recognize unfulfilled goals, prompting them to focus on relationships, pursue joy more fully, and establish meaningful new objectives [41].

Freedom is another core existential concern explored by Yalom [5]. While freedom entails the capacity to make choices, it simultaneously imposes responsibility, a burden that can generate anxiety. Individuals may, out of fear of responsibility, make choices that result in regret or dissatisfaction. Yalom emphasizes that embracing freedom and its inherent responsibility is vital for discovering meaning in life [5]. When individuals accept their freedom and make deliberate, responsible choices, those choices can directly contribute to growth and fulfillment [42]. For instance, a person who avoids decisions out of fear of mistakes may feel paralyzed when faced with critical choices. However, by embracing freedom and recognizing that responsible decisions, even imperfect ones, can lead to progress, they may find new direction and meaning in life [43].

Isolation is another central theme in existential psychology. Yalom notes that the realization of one’s ultimate aloneness, even in the company of others, can trigger emotional and psychological crises. However, he argues that accepting this isolation not only reduces anxiety but also fosters deeper connections with the self and with others [5]. By acknowledging their existential isolation, individuals may pursue meaning more profoundly, particularly in the context of human relationships and personal aspirations. For example, someone temporarily separated from a close relationship may experience deep loneliness. Yet, this solitude can become an opportunity for self-discovery, enabling them to clarify their values and to build more authentic, meaningful connections [5].

4.4. Meaninglessness as an Existential Crisis

Meaninglessness is another existential challenge extensively addressed by Yalom. At various stages of life, many individuals may experience a profound sense of nihilism, perceiving everything as devoid of purpose. Such feelings often arise from the loss of goals, connections, or values. However, Yalom contends that meaninglessness can be reframed as an opportunity to seek and construct personal meaning [26]. In this view, individuals must assume responsibility for creating new values and goals to restore significance in their lives. For example, a person who has lost a job or a cherished life project may initially experience despair and a sense of purposelessness. Yet if they reframe the crisis as a chance to reevaluate priorities, pursue meaningful relationships, or engage in altruistic activities, they can reconstruct a renewed sense of purpose [42].

Ultimately, according to Yalom, confronting existential crises, such as death, freedom, isolation, and meaninglessness should not be regarded as threats to mental health but as opportunities for growth and deeper self-understanding. When acknowledged and faced directly, these crises can serve as catalysts for constructing lives imbued with purpose, awareness, and authentic human connection [5, 42]. Yalom thus teaches that existential crises are not to be fled from but to be engaged as vital opportunities for meaning-making and personal fulfillment.

4.5. Integrating Broader Perspectives: Developmental, Digital, and Positive Psychology

The contradictions between scientific, philosophical, and psychological perspectives profoundly shape our understanding of life’s meaning. While some perspectives emphasize the absence of cosmic purpose, others highlight the individual responsibility to create meaning. Importantly, contemporary insights from developmental psychology and digital behavioral science show that existential concerns are not only abstract philosophical debates but also emerge from early relationships and modern socio-technological contexts.

4.6. Parenting Styles and the Genesis of Existential Conflict

Research indicates that the foundations of meaning construction are often laid or disrupted within the family environment. Parenting styles characterized by high control and low warmth have been linked to the emergence of maladaptive traits, such as emotional detachment, impulsivity, and existential disconnection [43]. These dynamics undermine identity stability and reduce tolerance for ambiguity, making existential crises more pronounced in adolescence and adulthood. From an existential developmental perspective, the absence of emotional attunement in childhood hinders the internalization of a coherent value system, weakening the psychological scaffolding required for meaning-making later in life.

For instance, authoritarian parenting may foster existential rigidity, as imposed values fail to integrate reflectively into personal identity. In contrast, authoritative parenting, balancing guidance with autonomy, supports psychological flexibility and a greater capacity for value-based meaning-making in uncertain contexts. These findings echo Frankl’s assertion that meaning arises not from external conditions but from interpretive and volitional engagement with them.

4.7. Digital Stress and the Collapse of Narrative Coherence

In parallel, the digital environment has created new forms of existential fragmentation. Adolescents and young adults are immersed in ecosystems of constant connectivity, rapid information flow, and performative self-presentation, all of which intensify psychological stress and erode reflective depth [44]. Digital stress, manifested in fears of missing out, negative social comparison, and exhaustion from continuous online engagement, undermines sustained attention and disrupts coherent identity formation.

This climate fosters what may be called algorithmic existentialism: the sense of being directed by impersonal digital systems (social media algorithms, feedback loops) that shape affective states and self-worth but provide no deeper framework for meaning. The absence of solitude and reflective silence, historically essential for philosophical inquiry, leaves many unable to construct enduring personal narratives. In this way, digital saturation mirrors the “cosmic indifference” of astrophysics: just as the universe appears cold and purposeless, the algorithmic environment appears indifferent to individual purpose, fostering a digital form of nihilism.

4.8. Positive Psychology and the Reclamation of Meaning

Against these existential dislocations, positive psychology offers empirically grounded pathways for reclaiming meaning. Martin Seligman’s PERMA framework situates meaning as one of the five pillars of psychological flourishing. Here, meaning involves connection to something larger than oneself, whether through social responsibility, creative expression, or relational commitment.

Unlike deficit-focused models, positive psychology emphasizes the intentional cultivation of meaning as a resource for resilience. Interventions, such as values clarification, future-self projection, and narrative therapy help individuals reconstruct coherent identity narratives and locate intrinsic sources of purpose. These practices not only mitigate stress but also foster resilience and motivation. Importantly, Seligman’s approach converges with existentialist philosophy: both traditions affirm that meaning is not passively found but actively made. Where existentialism underscores freedom as the foundation of responsibility, positive psychology translates this into structured interventions that enhance well-being in the face of uncertainty.

4.9. Synthetic Perspective: Foundations of Existential Philosophy and the Psychology of Meaning

Existential philosophy locates meaning not in universal laws or external systems but in individual experience and human choice. At its core, this tradition asserts that individuals must assume responsibility for the meaning of their lives because the world itself lacks inherent purpose; meaning must therefore be created from within [14]. Jean-Paul Sartre, in Being and Nothingness, famously declared that “existence precedes essence” [14]. This principle signifies that human beings first exist and only later define the nature and purpose of their lives through their choices. For Sartre, life has no preordained goal, and individuals bear the task of creating meaning by exercising freedom. He further develops the concept of self-awareness or awareness of freedom, which enables individuals to make authentic, autonomous decisions [14].

By contrast, the psychology of meaning, particularly in the work of Viktor Frankl and Aaron T. Beck, demonstrates how meaning can be cultivated through psychological processes, especially during times of crisis or adversity. Frankl argued that the search for meaning is essential for mental health and resilience [2]. In Man’s Search for Meaning, he emphasized that even in extreme conditions, such as concentration camps, individuals could discover meaning that sustained life. For Frankl, recognizing meaning in suffering allows individuals to transcend hardship and continue with purpose [2]. Similarly, Beck’s cognitive approach highlights the role of interpretive frameworks in shaping how individuals construct values and derive significance from lived experiences. Both perspectives suggest that through reflective awareness and intentional choice, individuals can generate meaning even in the face of suffering.

The integration of these two perspectives, existential philosophy’s recognition of the world’s meaninglessness and the psychology of meaning’s focus on personal responsibility and cognitive processes, provides a richer understanding of meaning in contemporary contexts. This synthesis has significant implications for enhancing psychological well-being, fostering personal empowerment, and strengthening social relationships. By acknowledging both the absence of inherent purpose and the individual’s capacity to create meaning, it becomes possible to navigate today’s complex and rapidly changing world with greater resilience and authenticity.

4.10. Freedom of Choice and Responsibility

A central principle of existential philosophy is the freedom of choice. This freedom, however, is often accompanied by existential anxiety and crisis. While many individuals experience fear or distress in the face of radical freedom, Frankl and other psychologists emphasize that freedom also provides the foundation for creating meaning. As Sartre famously declared, “Man is condemned to be free” [14]. Yet this freedom necessarily entails responsibility.

Consider an individual who feels emptiness and purposelessness in their workplace because they perceive no broader value or positive impact in their activities. From an existential perspective, such a person must recognize that the world itself is inherently meaningless, and it is therefore their responsibility to construct meaning. They may exercise freedom by altering their career path, setting new goals, or discovering motivation in the smaller, meaningful aspects of daily life.

4.11. Existential Challenges and the Crisis of Meaning

Individuals encountering crises, such as illness, bereavement, or career disruption, may experience despair and profound meaninglessness. In such contexts, existential philosophy and the psychology of meaning can serve as complementary resources. Existential thought helps individuals acknowledge the inevitability of death and the absence of predetermined meaning, while psychological approaches encourage them to continue creating meaning rather than succumbing to despair.

For example, a bereaved individual who loses a loved one may initially experience depression and existential emptiness. From an existential philosophical standpoint, they may come to accept that death is an unavoidable reality and, in the absence of universal meaning, must generate their own purpose through the grieving process. Simultaneously, psychological interventions, such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), can provide structured tools for coping with pain, fostering acceptance, and enabling the person to reconstruct meaning through conscious choices [45].

4.12. Integration and Implications

The integration of existential philosophy with the psychology of meaning holds profound implications for psychological well-being. When individuals embrace their freedom and responsibility while actively seeking meaning, they can achieve greater life satisfaction, reduced existential anxiety, and enhanced resilience. This synthesis not only aids in navigating crises but also promotes personal growth, empowerment, and the creation of a more meaningful life.

4.13. Theoretical Foundations of “Creating Meaning”

The concept of creating meaning is closely aligned with both existential philosophy and the psychology of meaning, each of which emphasizes individual freedom and human responsibility. Unlike traditional approaches that attempt to discover predetermined meaning in external phenomena, this perspective holds that meaning emerges from the individual’s own efforts and choices.

In existential philosophy, Jean-Paul Sartre is perhaps the most influential advocate of this view. Sartre argued that human beings possess no inherent essence; they must instead create meaning through their freedom of choice and acceptance of responsibility. His well-known assertion that “man is condemned to be free” reflects the idea that, in an inherently meaningless world, individuals must construct their own meaning [14]. In Being and Nothingness, Sartre maintains that there is no preordained purpose in life, and that humans must therefore use their freedom to shape meaningful existence [14]. This framework enables individuals to make choices with full responsibility and, through embracing freedom, to create personal meaning. For instance, a person confronting job loss or emotional turmoil may initially perceive life as purposeless. Yet, according to Sartre’s perspective, such a person must recognize that meaning depends on their choices; by redirecting their energy into a new career, cultivating hobbies, or engaging in altruistic acts, they can reconstruct meaning in life.

In psychology, Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy provides a parallel emphasis on creating meaning. Frankl argued that sustaining psychological health requires individuals to make their lives meaningful actively. Drawing on his experiences in Nazi concentration camps, he demonstrated that even under extreme suffering, individuals could maintain mental health and purpose by accepting responsibility for meaning and setting personal goals [2].

Contrasting with the finding meaning model, the creating meaning model places responsibility squarely on the individual. Life’s meaning is not externally revealed but internally generated. Both Sartre and Frankl insist that individuals cannot passively await life’s meaning to emerge; rather, they must exercise freedom and responsibility to construct it [2, 14].

4.14. Proposal for a Practical Framework for Creating Meaning in Everyday Life

To operationalize the creating meaning model in daily contexts, a practical framework can be developed that integrates principles from existential philosophy and the psychology of meaning. This framework emphasizes freedom, responsibility, and intentional action, guiding individuals toward generating constructive meaning in the face of everyday challenges. It consists of four key stages:

4.14.1. Setting Personal Goals Aligned with Values and Interests

The first stage involves identifying and pursuing goals that are consistent with one’s personal values and intrinsic interests [45].

4.14.2. Developing Self-awareness and Deeper Understanding

Self-awareness, ongoing reflection on one’s inner life and lived experiences, is critical to meaning-making. It enables individuals to recognize values and strengths, providing a foundation for purposeful choices [44].

4.14.3. Engaging in Meaningful Activities

Creating meaning requires active engagement in pursuits that not only yield practical benefits but also foster fulfillment, purpose, and alignment with core values.

4.14.4. Accepting Responsibility for Choices and Actions

A cornerstone of existential philosophy is the acceptance of responsibility. This entails acknowledging that individuals are ultimately accountable for their decisions and the lives they create [14].

4.15. Dynamic Recursive Model of Meaning-making

To conceptualize the dynamic and interactive structure of meaning-making in life, a recursive model can be employed in which psychological and existential variables evolve over time and mutually influence one another. This model highlights that meaning is not a static state but an ongoing process that emerges through crises, reflection, and personal growth.

Mathematical functions, such as the sigmoid (σ) and hyperbolic tangent (tanh) are used to model nonlinear human responses, reflecting the bounded and gradual nature of psychological capacity [31]. These functions illustrate how individuals’ responses to existential challenges are neither linear nor unlimited but instead develop progressively within psychological constraints.

This framework demonstrates that meaning is not a one-time achievement but the cumulative result of repeated confrontations with existential challenges, internal processing, and transformative adaptation. As Frankl emphasized, meaning is often discovered not in the absence of suffering but through one’s response to it. Similarly, crises, such as grief, identity loss, or major life transitions serve as catalysts for self-reflection, which in turn shape processes of growth and reconstruction [46].

Moreover, meaning and personal growth are closely linked to psychological well-being, with each reinforcing the other [33]. This reciprocal influence generates a feedback loop in which the construction of meaning supports resilience, and resilience, in turn, facilitates deeper meaning-making.

Findings from cultural existential psychology support this recursive perspective, demonstrating that human cognition responds to existential threats through adaptive, feedback-based mechanisms [31]. The recursive and time-sensitive character of this model thus captures the iterative nature of meaning-making, emphasizing that it is a lifelong, evolving process shaped by crises, reflection, and growth.

4.16. Application and Interpretation of the Dynamic Model

The proposed dynamic model provides a robust theoretical and computational framework for empirically investigating the psychological and philosophical structures of meaning in life. It is particularly well-suited for future research employing simulations, time-series analyses of psychological data, and clinical interventions designed to enhance meaning and well-being.

From an existential ontological perspective, the model emphasizes that meaning is not an external or absolute truth but a recursive outcome of an individual’s internal responses to life crises. This interpretation aligns with Frankl’s (2006) assertion that meaning emerges not in the absence of suffering but through the individual’s confrontation with it, coupled with the capacity to respond with agency and responsibility [2].

4.17. Example: Coping with Loss

Consider an individual who experiences the death of a close loved one as an intense existential crisis (Et). Initially, their perceived level of meaning (Mt) may decline as a result of shock, disorientation, and emotional turmoil. However, if the individual actively engages with the crisis (Ct), for example, by seeking therapy, engaging in philosophical reflection, or seeking social support, this engagement can stimulate personal growth (Gt). Such growth may manifest in greater emotional depth, enhanced empathy, or the restructuring of one’s worldview.

As Gt increases, it positively influences the construction of new meaning (Mt+1), which subsequently enhances psychological well-being (Pt). The recursive structure of the model captures this feedback loop: the growth and meaning achieved at time t+1 directly shape how the individual confronts future crises, progressively evolving their existential framework.

Theoretical Implications

The proposed dynamic model offers several important theoretical contributions:

- Simulation of Personality Traits: It enables the simulation of how different personality traits (e.g., variations in parameters ai, bi, di) adapt to existential crises.

- Modeling Temporal Dynamics: It allows for modeling the temporal lag between the occurrence of a crisis and the subsequent restoration of psychological well-being.

- Testing Interventions: It provides a platform for testing the potential effects of interventions by adjusting initial conditions, for example, enhancing freedom (F) through therapeutic support or strengthening responsibility (R) via coaching.

Overall, this dynamic model advances beyond static theories of meaning by highlighting the evolving, self-correcting, and nonlinear nature of human existential development. This perspective aligns with cultural existential psychology, which emphasizes the role of culture in shaping human responses to suffering and existential threat [31].

The findings of this study further suggest that, despite the challenges posed by scientific and cosmological perspectives portraying the universe as purposeless and random, the possibility of creating meaning in human life persists. Meaning is not an inherent or predetermined truth; rather, it is an active, dynamic process shaped by conscious choice and the acceptance of individual responsibility. In other words, the meaning of life emerges from the ongoing interaction between individuals and their world and is internalized most deeply in response to existential crises and uncertainty.

By integrating philosophical, psychological, and scientific perspectives, this study offers a multidimensional and enriched understanding of life’s meaning, one that transcends the dichotomy between nihilism and the search for external meaning. Instead, it underscores the uniquely human capacity to create meaning, adapt to difficult realities, and construct personal values. Thus, meaning in life should be regarded not as a passive discovery but as an active and continuous choice enabling individuals to cultivate rich, purposeful lives even within a seemingly indifferent and aimless universe.

4.18. Conceptual Extension: A Recursive Model of Meaning-making

As a theoretical extension of this integrative review, a recursive model of meaning-making is proposed (see Appendix A). This model conceptualizes the cyclical dynamics of existential disruption, psychological coping, reflective processing, and renewed engagement with value-driven action. Although mathematical in form, the model primarily functions as a metaphorical representation of the iterative nature of personal development in the face of existential challenges. While not yet empirically validated, this recursive framework provides a foundation for future interdisciplinary research that may integrate computational modeling, psychological theory, and therapeutic practice.

4.19. Interdisciplinary Tensions and the Paradox of Meaning

4.19.1. The Scientific View: Randomness and Indeterminacy in Physics

Contemporary physics, particularly quantum mechanics, portrays the universe as fundamentally probabilistic rather than deterministic. Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle asserts that it is impossible to know both the position and momentum of a particle with absolute precision [47]. This directly challenges the Newtonian worldview of predictability and control. For example, in observing electrons, one cannot determine their exact location but only the probability of where they may be found. This has led to the scientific interpretation that reality, at its core, lacks a fully deterministic structure.

Cosmological models, such as the multiverse hypothesis [48], extend this indeterminacy further by suggesting that our universe may be just one among countless others, each governed by its own physical laws. Within this framework, the anthropic principle that the universe appears fine-tuned for life may not signify purpose but statistical inevitability: given infinite possibilities, at least one universe would support the emergence of life. Such perspectives radically decenter humanity’s place in the cosmos and undermine traditional notions of cosmic intentionality or teleology.

4.19.2. Existentialism: Human Freedom in an Absurd World

While physics depicts a disenchanted and impersonal universe, existential philosophy places the responsibility for meaning squarely on the human subject. Sartre [49], for example, argued that since there is no God or predetermined essence, humans are “condemned to be free,” free to choose, to act, and to construct values. Yet this freedom is not inherently liberating; it produces existential anxiety. Sartre illustrates this with the example of a young man during World War II who must choose between caring for his ailing mother or joining the Resistance. With no universal moral law to guide him, he faces the full weight of freedom: the necessity of choosing, and the responsibility for the consequences of that choice.

Albert Camus [50], in The Myth of Sisyphus, compares the human condition to the fate of Sisyphus, condemned to roll a boulder uphill for eternity. Despite the absurdity of the task, Camus insists that Sisyphus must be imagined happy, for meaning is not discovered but created through conscious defiance, lucidity, and acceptance of life’s absurdity.

4.19.3. Psychological Theories of Meaning-making

Psychologically, the pursuit of meaning is deeply intertwined with human well-being. Viktor Frankl, drawing on his survival in Auschwitz, observed that those who endured extreme suffering were often those who maintained a sense of future-oriented purpose. One prisoner survived by holding onto the hope of finishing a lost manuscript; another by recognizing his responsibility to a child who depended on him.

Modern therapeutic approaches extend this insight. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), for example, encourages individuals to acknowledge life’s pain and ambiguity while choosing to live in alignment with deeply held values [51]. A grieving individual might, for instance, channel their love into volunteer work, thereby transforming suffering into purposeful action. Such models do not aim to eliminate existential pain but to foster psychological flexibility, enabling people to navigate uncertainty while remaining committed to what matters most.

4.19.4. The Paradox of Meaning in a Disenchanted Universe

This interdisciplinary tension culminates in what can be termed the paradox of meaning: if the universe is silent, indifferent, and chaotic as modern science often suggests, why do humans persist in searching for purpose? Can meaning exist without metaphysical grounding?

A real-world example illustrates this paradox. From a scientific perspective, death is nothing more than the cessation of biological function, no soul, no afterlife. Yet in moments of grief, people intuitively construct meaning. A parent who loses a child might say, “She was taken for a reason,” even while knowing that the cause was a random genetic condition. This response reveals a deep psychological need to interpret events narratively and existentially, often in defiance of scientific explanation.

In this sense, the human being functions as a meaning-generating organism in a cosmos that offers no inherent stories. We tell ourselves narratives not because they are objectively true, but because they allow us to endure, to keep living, and to reconstruct a sense of purpose in an otherwise indifferent universe.

4.19.5. Toward Integration: A Constructivist View of Meaning

Rather than treating insights from philosophy, psychology, and science as mutually exclusive, a more productive approach is to integrate them. The randomness revealed by physics does not negate the possibility of meaning; rather, it shifts the locus of meaning from the cosmos to the individual. Meaning becomes relational, contextual, and constructed.

For example, while string theory or quantum fluctuations cannot explain why a person chooses to become a nurse, existential and psychological frameworks can. Such a choice may derive significance from caregiving, responsibility, or generativity concepts absent in the vocabulary of cosmology but central to human experience.

In this view, meaning is not discovered like a universal law but actively constructed through values, relationships, and intentional action. We do not find meaning; we build it. Crucially, this construction occurs not in defiance of a meaningless universe but as a creative human response to it.

CONCLUSION

This study set out to explore whether it is possible to construct a valid and sustainable sense of life’s meaning in a world that appears inherently purposeless. Drawing on philosophical, psychological, and cosmological perspectives, the findings suggest that although the universe itself may lack intrinsic purpose, human beings possess both the capacity and the necessity to generate meaning through free choice, self-awareness, and personal growth.

From a philosophical perspective, existentialism and nihilism frame meaning not as a pre-existing truth but as something forged through individual agency and conscious engagement with uncertainty. Psychologically, Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy demonstrate that meaning-making functions as a powerful coping mechanism in the face of suffering, directly supporting resilience and well-being.

The dynamic mathematical model proposed here conceptualizes meaning as an evolving, recursive process shaped by existential disruption, coping strategies, personal development, and feedback loops between these elements. This model captures the temporal, adaptive, and transformative character of meaning-making as a lifelong journey.

Furthermore, insights from cosmology, particularly multiverse theories, expand the philosophical horizon of the debate, challenging anthropocentric assumptions and inviting new reflections on humanity’s place in an indifferent cosmos.

In sum, this integrative review argues that while the cosmos may be inherently purposeless, individuals retain the power to construct meaning as a pathway toward psychological health and existential clarity. Meaning is not passively found but actively created, a continuous process essential not only for personal fulfillment but also for navigating existential crises in the contemporary world. Future research should continue to advance interdisciplinary models that bring together cutting-edge science and humanistic inquiry, thereby deepening our understanding of life’s purpose and potential.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

The author confirms sole responsibility for the conception, design, writing, and final approval of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| IR | = Integrative Review |

| PRISMA | = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

PRISMA checklist is available as supplementary material on the publisher’s website along with the published article.

APPENDIX A: RECURSIVE MODEL OF MEANING-mAKING

This appendix presents a theoretical recursive model designed to conceptualize the dynamic interaction between existential disruption, psychological coping mechanisms, and personal meaning construction. The model is expressed in a simplified mathematical form, serving as a metaphorical representation of the cyclical adaptation process rather than a fully empirical framework.

Equation:

M(t+1) = αC(t) + βE(t) − γS(t)

Where:

• M(t) = Level of perceived meaning at time t

• C(t) = Coping strategies employed

• E(t) = Existential insight or reflection

• S(t) = Stress or existential disruption

• α, β, γ = Weighting parameters (context-dependent)

This recursive relationship suggests that meaning evolves through the interaction between coping processes and existential variables. It is not intended as a predictive or empirical model but as a conceptual foundation for future interdisciplinary research that integrates philosophical, psychological, and computational perspectives.