All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Exploring Coping Strategies in Response to Stress among Prisoners: A Comprehensive Scoping Review

Abstract

Background

Prisoners often experience psychological distress due to incarceration, legal uncertainty, and the disruption of social relationships. These conditions increase the risk of mental health problems, including anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Coping strategies are essential in helping individuals manage these stressors and are key to successful reintegration after release.

Objective

This study aims to systematically review the coping strategies employed by prisoners in response to psychological distress and to examine their impact on mental health and reintegration outcomes.

Methods

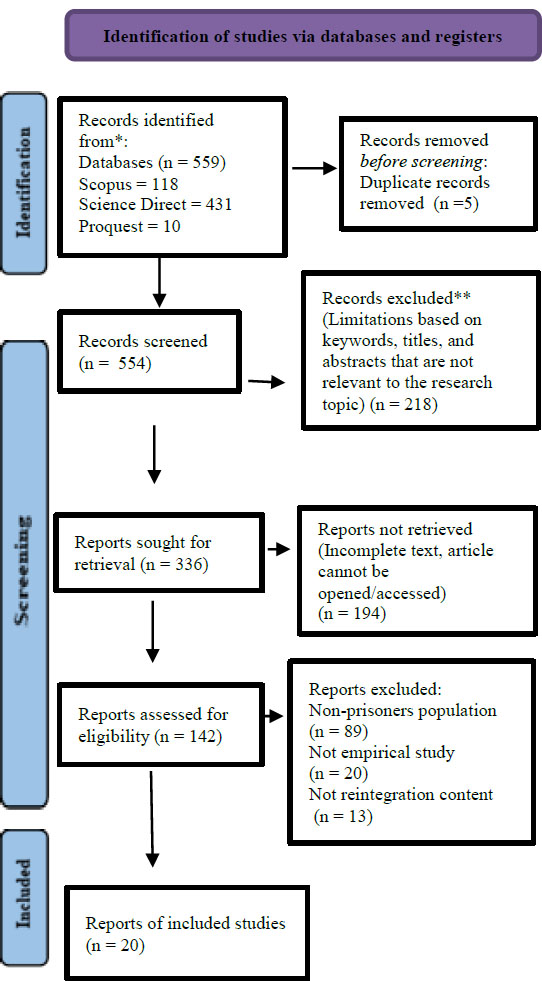

The research employs a scoping review with PRISMA-ScR (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews) guidelines. Literature searches were performed in Scopus, ProQuest, and ScienceDirect using the keywords “coping strategy,” “reintegration,” and “prisoner.” Inclusion criteria focused on peer-reviewed articles published between 2000 and 2025. Of the 559 articles identified, 20 studies were included in the final review.

Results

The findings indicate that prisoners utilize both adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies. Maladaptive strategies such as denial, withdrawal, aggression, and substance use were commonly associated with higher levels of psychological distress. In contrast, adaptive strategies such as problem-solving, cognitive reframing, spiritual coping, and seeking social support were linked to better psychological well-being and improved reintegration outcomes.

Conclusion

Coping strategies significantly influence prisoners' mental health and their ability to reintegrate into society. Promoting adaptive coping in correctional settings, particularly through interventions that enhance emotional regulation and resilience, is essential. Further research is recommended to explore coping variations by case type and assess the effectiveness of tailored support programs.

1. INTRODUCTION

Incarcerated individuals are particularly vulnerable to mental health issues [1], attributable to both the stress of incarceration and the challenges of reintegration, including poor interpersonal relationships, social stigma, and inadequate social support [2]. The prison environment is frequently characterized as both unpleasant and stressful, thereby predisposing prisoners to psychological disorders such as stress, anxiety, and depression, which can have significant and far-reaching consequences for their physical, mental, and emotional well-being [3, 4]. Depression is the most prevalent mental health issue encountered among prisoners, often precipitated by the pressures associated with legal problems; furthermore, such depressive states may lead to the adoption of maladaptive coping mechanisms, including self-harm [5]. Research [6] shows that prisoners during 6-12 months of detention engage in maladaptive coping behavior that is detrimental to themselves [7]. In several cases of drug-addicted prisoners attempting suicide, this response is a maladaptive strategy that is considered capable of reducing pressure, stress, and negative emotional states [8]. Female prisoners also show coping patterns in dealing with separation from family, namely by blaming themselves and denying their condition [9]. This situation certainly needs attention from the correctional system; prison staff must have the knowledge to train prisoners in adaptive stress management [10]. The prevalence of mental disorders among prisoners is positively correlated with the experience of detention, with a substantial body of research demonstrating the deleterious impact of incarceration on mental health [11]. Notably, individuals exhibiting a Type D personality, characterized by elevated levels of negative affectivity and social inhibition, appear particularly vulnerable to such disorders. Consequently, establishing robust social support networks is essential as a coping strategy to mitigate the adverse effects of mental health issues [12]. Lazarus and Folkman [13] argued that coping strategies are vital mechanisms through which individuals manage, adapt to, and overcome stress. Managing stress involves the regulation of thoughts, emotions, behaviours, physiological responses, and environmental conditions. Coping with stress involves regulating thoughts, feelings, behavior, physiological responses, and environmental conditions [14]. Conversely, maladaptive coping strategies, such as avoidance, significantly contribute to heightened levels of anxiety among inmates [15].

Individuals within correctional settings who have previously exhibited suicidal behaviors frequently present with heightened levels of anxiety, avoidance, and dependence on maladaptive coping mechanisms. This pattern of symptoms is often linked to an underlying sense of hopelessness [16]. Suicidal behavior in incarcerated populations can be conceptualized as a dysfunctional coping response to stress and negative affect [8]. Moreover, the inherent stressors of imprisonment appear to promote the development and utilization of ineffective cognitive coping strategies [17]. The inherent uncertainties and stressors associated with carceral environments demand resilience and effective coping mechanisms among incarcerated individuals [18]. Research indicates a correlation between resilience, perceived quality of life, and the tendency to adopt positive religious coping strategies within prison populations [19]. Moreover, studies reveal that prisoners serving longer sentences (exceeding 12 months), those with less severe sentences, and individuals receiving social support are more inclined to utilize positive coping strategies, such as seeking emotional support, engaging in religious practices, adopting problem-focused approaches, and making meaning of their experiences [20, 21]. Nonetheless, evidence also suggests that prisoners frequently rely on a singular coping strategy or alternate between strategies in response to specific situational demands [22]. Coping strategies are influenced by a multitude of factors, including cultural background, personal experience, environmental context, and individual personality traits [23]. These strategies comprise psychological and behavioural tools that individuals utilise to manage and mitigate stress and pressure. Effective problem-solving and adaptive skills are essential for maintaining mental and emotional well-being, fostering resilience, and enabling individuals to navigate challenging situations [24]. This adaptive capacity involves deliberate cognitive and behavioural processes aimed at managing conflict and addressing both internal and external demands, thereby contributing to overall well-being and resilience.

Coping skills involve the utilisation of both personal and environmental resources to manage stress. Essentially, these strategies encompass cognitive and behavioural responses that enable individuals to deliberately draw on their competencies as well as external supports to mitigate conflict and enhance psychological well-being [22]. In addition to internal factors, family support plays a pivotal role in shaping the emotional coping strategies of prisoners [25]. The capacity of prisoners to adapt and cope with stress underpins their ability to manage the responsibilities and pressures arising from their behaviors. Although such behaviors may occasionally manifest as negative responses, they can also be constructive when reinforced by family support and an effective correctional system. This positive support enables prisoners to maintain lower stress levels, manage challenges effectively, and achieve favorable outcomes [26]. A comprehensive review of the literature on coping strategies among prisoners over the past decade has identified both adaptive and maladaptive coping mechanisms. These mechanisms enable prisoners to adjust to detention [27], mitigate aggressive behaviour [28], manage stress, and enhance mental health [15, 29]. Notwithstanding existing research, relatively few studies have examined the relationship between prisoners' coping strategies, the type of criminal case, and interventions designed to foster adaptive coping. This study addresses a critical gap in the literature, as adaptive coping strategies have been shown to mitigate mental health problems [21, 30, 31], improve prisoners' psychological well-being [32], and enhance psychological resilience [33, 34].

In line with the study's objectives, two key research questions have been formulated:

- What psychological responses and coping strategies are adopted by prisoners?

- Which factors serve to strengthen these coping strategies?

The study seeks to identify the range of psychological responses and coping strategies employed by prisoners. It is hypothesized that prisoners undergoing adaptation while receiving inadequate support will exhibit negative emotional responses. Moreover, it is anticipated that prisoners convicted of serious crimes, such as drug-related offenses or murder, may also display adverse emotional reactions. Effective interventions for fostering adaptive coping strategies will additionally be explored.

This research has significant implications for future studies, encouraging comparative analyses and integrating its findings with emerging research in related fields. The study's outcomes will provide valuable insights for prison staff, community counsellors, and mental health professionals, thereby enhancing their understanding of prisoners' psychological responses, coping mechanisms, interventions, and associated challenges.

2. METHODOLOGY

This scoping review employs a comprehensive methodology to identify and synthesise literature from diverse sources, utilising a range of research methodologies pertinent to the topic [35]. The primary objective is to address predetermined research questions by aggregating and analyzing relevant literature, which is subsequently categorized according to the framework developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute [36], drawing on the work of Arksey and O'Malley [37]. This study adopted the PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) rather than the traditional PRISMA framework because its primary objective is to map the breadth and diversity of coping strategies in prison populations, rather than evaluating the effectiveness or quality of interventions. PRISMA-ScR is better suited for exploratory objectives and allows the inclusion of heterogeneous study types (qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods) to capture a comprehensive landscape of the literature. In contrast, traditional PRISMA is typically used for systematic reviews focusing on intervention effectiveness and tends to include only randomized controlled trials or experimental designs.

Compared to traditional PRISMA, which is primarily designed for evaluating the effectiveness of interventions through randomized control trials (RCTs), PRISMA-ScR allows for broader inclusion criteria and is suitable for identifying key concepts, research gaps, and types of evidence available in a given field. In this review, the heterogeneity in study designs, participant characteristics, and conceptual frameworks necessitated the use of PRISMA-ScR rather than PRISMA. For instance, while PRISMA emphasizes risk of bias assessment and meta-analysis, PRISMA-ScR emphasizes transparency in mapping the scope and nature of evidence without synthesizing quantitative findings. This methodological choice aligns with recent works [38], which also used PRISMA-ScR to map literature on digital twin applications in construction, recognizing the diversity of approaches and the evolving nature of research in that field

The study was conducted in several stages, comprising the following:

2.1. Search Strategy

Prior to initiating the literature search, the researcher employed the PEO (Population, Exposure, Outcome) framework to determine appropriate search keywords and formulate the research questions. The PEO framework is outlined as follows:

- Population: Prisoners

- Exposure: Problems encountered during detention and social reintegration

- Outcome: Stress, anxiety, and difficulty adapting\

The literature search was conducted across three databases—Scopus, ProQuest, and ScienceDirect—with the search criteria focusing on coping strategies among prisoners, particularly emphasizing their psychological conditions and adaptive capacities. This scoping review protocol adheres to the PRISMA-ScR reporting guidelines [39]. Keyword searches utilized the terms “coping strategy,” “reintegration,” and “prisoner.” The inclusion of “reintegration” was deliberate, given that psychological problems frequently emerge during both detention and the reintegration process. The search results also generated several related terms, including psychological distress, resilience, mental health, well-being, and quality of life. These terms informed the analysis of coping strategy mechanisms among prisoners. To ensure consistency, the same keywords were applied across all searches, thereby facilitating the retrieval of pertinent research articles. A comprehensive search conducted in March 2025 yielded a total of 559 articles: 10 from ProQuest, 118 from Scopus, and 434 from ScienceDirect.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

This scoping review aimed to identify coping strategies—both adaptive and maladaptive—employed by prisoners in response to stress. Initially, the research team conducted a preliminary search to identify existing gaps and to inform the development of research questions and objectives. Clear inclusion and exclusion criteria were subsequently established. The review focused on prisoners serving their sentences or undergoing social reintegration. It examined patterns of coping strategies among prisoners in correctional institutions and detention centres, with the search criteria refined during the title and abstract screening phase to exclude studies focusing on prison officers or staff. Keywords related to coping behaviours, such as psychological distress, resilience, mental health, well-being, and quality of life, were incorporated into the analysis. In accordance with the scoping review protocol, the following criteria were applied: (1) Studies investigating adaptive and maladaptive coping strategies among prisoners were of primary interest, (2) Only primary studies employing qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods designs were included. Systematic reviews, books, chapters, letters, comments, editorials, dissertations/theses, conference abstracts, and case studies were excluded.

2.3. Study Selection

All search results were downloaded and imported into the Mendeley reference management tool in RIS format, which is specifically designed for systematic and methodical literature reviews. Following compilation, the researchers removed duplicate articles, and the remaining articles were screened by the research team. From the initial 559 articles retrieved from three databases, duplicate removal resulted in 554 unique articles. Screening commenced with evaluations of titles and abstracts using predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria, followed by full‐text reviews to determine eligibility for data extraction. Of the 554 articles, 336 proceeded to the screening stage based on title, abstract, and keyword selection. The suitability of the data at this stage was ensured through clarifications and refinements of the selection criteria, repeated adjustments of the inclusion/exclusion parameters, and independent review of the remaining articles prior to data extraction [40].

2.4. Data Extraction and Extraction Process

The researcher conducted a comprehensive review of all literature meeting the specified criteria, evaluating each article in its entirety to determine its eligibility for data extraction. Following the screening process—during which the predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the initial 559 articles—20 articles were deemed eligible and aligned with the research objectives. Data extraction entailed the systematic documentation of key variables, including article title, author(s), year of publication, journal title, country of origin, research objectives, research methodology, and research findings.

2.5. Data Summary and Synthesis of Results

At this stage, the researcher conducts a thematic mapping of the coping strategy mechanisms employed by prisoners in response to stress. A descriptive analysis of these mechanisms is provided. It is recognised that psychological distress among prisoners may be precipitated by a range of factors, including the stress associated with detention, inadequate family support, social stigma, and other related variables. This study examines the role of coping strategies in influencing the psychological conditions of prisoners, focusing on aspects such as well-being, quality of life, psychological distress, resilience, and mental health. A substantial body of research indicates that coping mechanisms significantly impact the psychological outcomes of prisoners. A total of 20 articles, deemed eligible for inclusion, will be subjected to a comprehensive analysis, the results of which are summarised in the Literature Review Summary Matrix (Table 1).

2.6. Review Team and Consultation

The literature review was conducted by doctoral student researchers in consultation with their promoters and co-promoters. Additionally, stakeholders in prisons and detention centers were consulted to provide further insights into the study's background, design, sample selection, participant information, data collection and analysis methods, results, conclusions, and limitations, as identified by both the authors and reviewers.

| No | Author & Year | Country | Participant |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [41] | Australia | 81 male prisoners |

| 2 | [42] | UK | 203 male adolescents |

| 3 | [43] | UK | 141 male prisoners |

| 4 | [44] | UK | 204 inmates |

| 5 | [45] | USA | 24 ex-prisoners |

| 6 | [46] | Poland | 390 male prisoners |

| 7 | [47] | Australia | 366 male inmates |

| 8 | [36] | USA | 518 ex-prisoners |

| 9 | [27] | Indonesia | 118 female inmates |

| 10 | [48] | Georgia | 6 adult males former |

| 11 | [25] | Indonesia | 33 female inmates |

| 12 | [49] | Turkey | 33 ex-offenders |

| 13 | [50] | Philippines | 6 ex-offenders |

| 14 | [51] | South Africa | 418 inmates |

| 15 | [41] | USA | 10 ex-convict |

| 16 | [52] | India | 200 inmates (169 male, 31 female) |

| 17 | [53] | Switzerland | 50 older prisoner |

| 18 | [54] | Philippines | 5 ex-offenders |

| 19 | [55] | Ghana | 243 prison officers |

| 20 | [56] | USA | 9 male young prisoners |

The literature search, conducted across three databases, initially yielded 559 articles (Fig. 1). Following the removal of duplicates, 554 articles remained. After title and abstract screening, 142 potentially relevant articles were selected for full-text review. Subsequently, 122 articles were excluded for the following reasons: (1) the study population did not consist of prisoners, (2) the study employed a non-empirical design, and (3) the article was unrelated to coping strategies. Consequently, 20 articles were selected for data extraction and synthesis of results (Fig. 1).

PRISMA 2020.

| No | Author & Year | Methodology | Coping Style |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | [41] | Cross-sectional survey | Emotionally Focused, Avoidant |

| 2 | [42] | Cross-sectional with CSQ-3, GHQ-28 | Emotional, Avoidant, Rational |

| 3 | [43] | Cross-sectional with SEM | Maladaptive Coping |

| 4 | [44] | Comparative cross-sectional | Problem vs emotionally focused |

| 5 | [45] | Mixed Methods | Avoidance (substance abuse) |

| 6 | [46] | Cross-sectional with COPE | Constructive vs Denial |

| 7 | [47] | SEM-based survey | Avoidance, Support, Acceptance |

| 8 | [36] | Longitudinal quantitative | Support Coping |

| 9 | [27] | Predictive linear regression | Emotion-focused |

| 10 | [48] | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | Adaptive coping (spirituality, work, and sport) |

| 11 | [25] | Cross-sectional correlation | Emotional-focused |

| 12 | [49] | Qualitative (semi-structured interviews) | Adaptive coping (employement-related, social support) |

| 13 | [50] | Qualitative (phenomenology) | Adaptive Coping (community support) |

| 14 | [51] | Quantitative (correctional design) | Problem-solving, avoidance |

| 15 | [41] | Qualitative (phenomenology) | Positive coping, spirituality, resilience |

| 16 | [52] | Cross-sectional descriptive survey | Low/high approach & avoidance coping |

| 17 | [53] | Qualitative interview study | Maladaptive coping (radical acceptance, self-expression) |

| 18 | [54] | Qualitative (thematic analyisis) | Adaptive coping (community engagement, positivity) |

| 19 | [55] | Cross-sectional survey | Adaptive coping (talking to colleagues) |

| 20 | [56] | IPA (interpretative phenomenological analysis) | Adaptive coping (emotional suppression, meaning-making) |

3. RESULTS

The following is a report on the literature review selection process.

Flow Diagram for updated systematic reviews based solely on database and register searches.

Based on the PRISMA data, the following summary synthesizes the literature on coping strategies among prisoners.

Based on Table 2, research findings are presented as an interesting distribution.

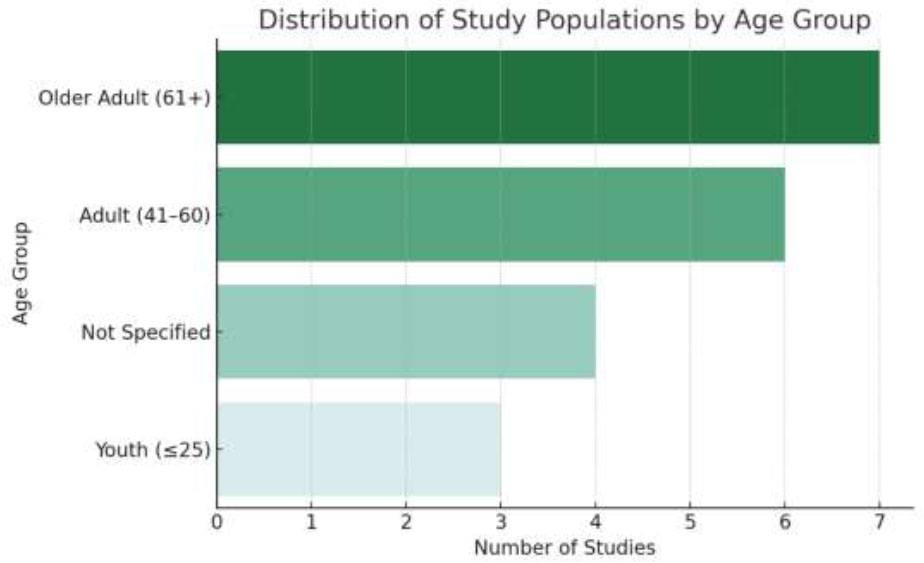

3.1. Distribution of Study Populations

The chart illustrates how research participants are distributed across different age groups:

- Adult (41–60 years) and Young Adult (26–40 years) categories are the most studied, indicating a strong research focus on individuals in their prime working and rehabilitation years. These age groups are often at the center of prison rehabilitation programs, job training, and reintegration planning.

- Youth (≤25 years) represent a substantial portion of the studies, highlighting interest in developmental vulnerability, emotional coping, and preventive interventions among juvenile and young offenders.

- Older Adults (61+ years) are emerging as a distinct category, particularly in research focusing on chronic stress, loss of autonomy, and coping in long-term incarceration.

- Not Specified includes studies that do not clearly report age ranges, often due to qualitative designs or focus on broader themes such as reentry or spiritual resilience.

The dominance of adult and young adult age groups in research reflects the practical focus on inmates who are most likely to benefit from psychological and vocational interventions. The attention to youth suggests early correctional influence is critical, while growing interest in older inmates reveals concern for a population that faces unique psychological and health-related challenges. Future studies could benefit from a more balanced representation of ages to address age-specific needs across the correctional lifespan.

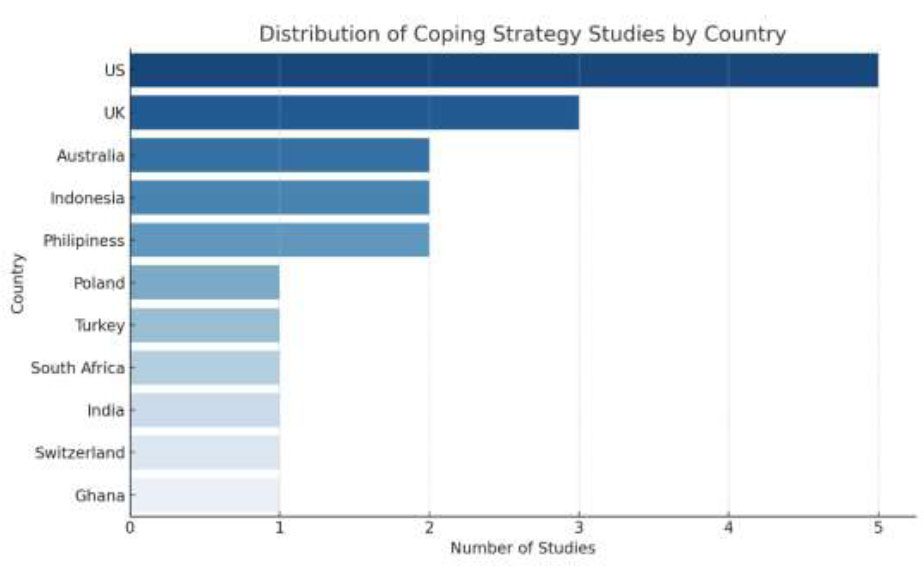

3.2. Distribution of Studies by Country

The chart illustrates the distribution of 20 empirical studies on inmate coping strategies across different countries. The United States leads with the highest number of studies (5 studies), reflecting its significant academic interest and investment in correctional psychology and prison rehabilitation research. The United Kingdom follows with 3 studies, and Australia with 2 studies, both of which have well-established criminal justice and psychological research infrastructures. Interestingly, countries from the ASEAN region, including Indonesia and the Philippines, are also represented. Indonesia contributes 2 studies, focusing specifically on female inmates and the role of family support, signaling the country's growing research attention toward gender and socio-cultural dimensions of incarceration. The Philippines is represented by 2 studies, which emphasize the reintegration experiences and coping mechanisms of former offenders in community settings. This inclusion of ASEAN countries like Indonesia highlights the broadening of the scope of prison-related psychological research beyond Western contexts, offering culturally grounded insights and the potential to inform localized intervention programs based on unique social and familial structures.

Distributions of study population.

Distribution of studies by country.

Distribution of most frequently research themes.

3.3. Distribution of Most Frequently Research Themes

The studies on inmate coping strategies reveal a diverse range of research themes, each addressing critical psychological and systemic aspects of incarceration and reentry. The most prominent themes include:

3.3.1. Coping Strategies and Psychological Well-Being

Several studies examine how inmates’ coping mechanisms, such as emotion-focused, problem-focused, and avoidance coping, affect their levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and overall psychological adjustment while in custody. Research [41, 42], showed that prisoners tend to use emotional and avoidance-focused coping, which is a predictor of low psychological well-being and vulnerable to psychological distress. The two studies highlight the significant role of emotion-focused coping in predicting psychological distress among incarcerated individuals. Gullone found that reliance on emotion-focused coping was the strongest indicator of reduced psychological well-being, whereas avoidance coping appeared to have a positive effect when emotional coping was statistically controlled. Similarly, Ireland reported that young offenders who frequently used emotional, avoidant, and detached coping strategies experienced higher levels of psychological distress compared to juvenile offenders. In both age groups, emotional coping was consistently linked to increased distress. These findings suggest that emotional coping may serve as a maladaptive strategy across different prison populations, emphasizing the need for interventions that promote more adaptive coping mechanisms [44]. This theme highlights how coping strategies used by prisoners directly impact aspects of psychological well-being, such as depression, anxiety, self-esteem, and subjective quality of life. Research on this theme typically compares different coping styles—such as problem-focused, emotion-focused, and avoidance coping—and how each contributes to psychological well-being during incarceration. Common findings suggest that emotional coping is often associated with decreased mental well-being, while adaptive coping, such as problem-solving and social support, tends to increase well-being.

3.3.2. Resilience

This theme explores resilience in the face of the stresses of prison life, including loss of freedom, social isolation, and past trauma. Research on this topic often highlights coping strategies that include acceptance, meaning in life, positive reframing, spirituality, and constructive activities such as studying or working. Resilience is considered an important mediator in maintaining psychological stability and reducing the risk of mental disorders during imprisonment and after release [45].

3.3.3. Youth Coping

Research in this theme emphasizes the importance of understanding the coping styles of adolescent and young inmates, as they have different psychological developmental challenges than adults. Studies in this category reveal that adolescents are more likely to use emotional, avoidance, and detached coping [28]. Young offenders used emotional, avoidant, and detached coping [44], which contributes to increased psychological distress. This theme supports the importance of age-appropriate interventions that instill healthy coping strategies early on.

3.3.4. Personality and Distress

This theme focuses on the relationship between maladaptive personality traits, coping styles, and psychological distress. Research shows that personality traits such as antisocial, asocial, and anxious/dramatic are often correlated with the use of maladaptive coping [44]. Inmates with maladaptive personality also affect lower quality of life, tend to use denial, mental and behavioral disengagement, and substance use [46]. This theme is important because it helps explain the internal mechanisms that influence how prisoners cope with stress, and opens up space for psychological interventions that target specific personality structures.

3.3.5. Reentry Challenges

This theme focuses on the transition from prison to the community, which is often a critical period for ex-offenders. Research in this category explores psychological and social barriers, including social stigma, employment limitations, and lack of family support [47]. These studies suggest that ineffective coping, such as avoidance and substance abuse, may increase the risk of recidivism. Major challenges included employment discrimination, social exclusion, mental health struggles, and bureaucratic/legal barriers. Supportive employment programs, family/community support, and access to mental health services improved reintegration outcomes [48, 49]. In contrast, coping based on family support, spirituality, and problem-solving skills may facilitate more successful reintegration [50].

These five themes reflect a spectrum of approaches to understanding coping among prisoners, ranging from individual to systemic, from internal psychological contexts to external social challenges.

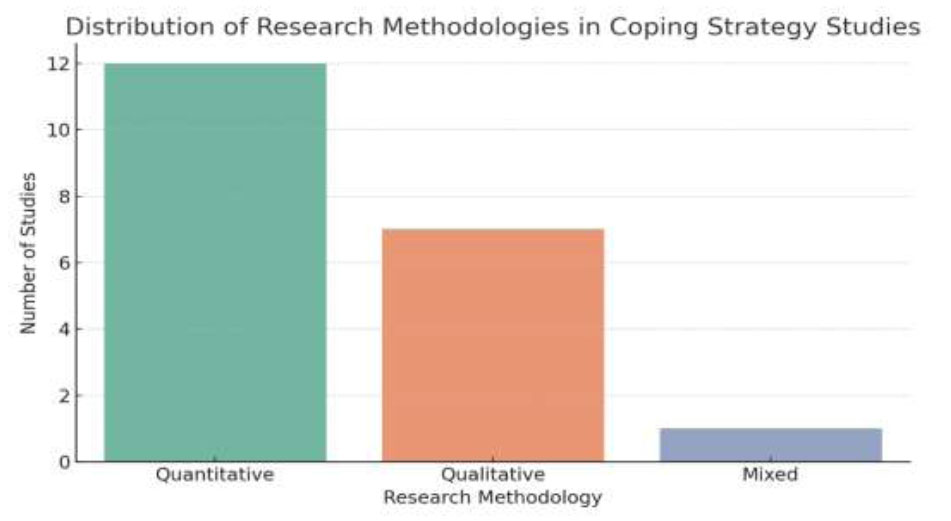

3.4. Distribution of Research Methodologies

3.4.1. Quantitative Methods (12 Studies)

Characteristics: Using standardized and tested instruments (e.g., COPE Inventory, GHQ-28, PAQ, Brief COPE). This approach allows for statistical analyses such as regression, SEM (Structural Equation Modeling), and correlation.

3.4.1.1. Research Focus

Measuring the relationship between coping styles and psychological symptoms (depression, anxiety, stress, etc.). Assessing the influence of demographic variables, sentence duration, and personality type on coping strategies. Explaining the effects of coping on adjustment, quality of life, and reintegration success.

3.4.1.2. General Findings

Emotion-focused coping is often associated with increased psychological distress.

Avoidance coping has mixed results; sometimes it appears to be helpful, especially when emotional coping is controlled for.

Distribution of research methodologies.

| Psychological Response | Strengthening Factor |

|---|---|

| Depression, anxiety, stress | Family & peer support |

| Emotion-focused coping | Rational/problem-focused coping, self-regulation |

| Avoidance, withdrawal | Structured rehabilitation, spiritual growth |

| Adjustment difficulties | Supportive prison climate, education programs |

| Trauma and suppression | Cognitive reframing, resilience, and mentorship |

Problem-focused coping and social support are associated with better psychological outcomes.

3.4.2. Qualitative Methods (7 Studies)

Characteristics: Using approaches such as phenomenological analysis, narrative inquiry, and thematic analysis. Data were collected through semi-structured or unstructured interviews.

3.4.3. Mixed Methods (1 Study)

Characteristics: Combines in-depth interviews with a coping measurement tool (CISS). Provides statistical and narrative data simultaneously for cross-validation.

Research Focus:

This study examines coping during reentry and why some ex-offenders experience failure to reintegrate (recidivism).

3.5. Psychological Responses to Incarceration and Factors That Strengthen Coping Strategies

During their detention, prisoners tend to show negative psychological responses that affect their ability to adapt. A literature review shows several psychological responses, including:

3.5.1. Distress and Mental Health Issues

Many prisoners show high levels of depression, anxiety, and stress [43, 51, 41]; [52]. This distress is often triggered by restrictive prison conditions, social isolation, stigma, and lack of autonomy.

3.5.2. Maladaptive Coping

Common responses to distress include maladaptive coping such as emotion-focused coping, avoidance, substance use, denial, or withdrawal, which actually worsen psychological well-being [44, 47, 53].

3.5.3. Trauma and Emotional Suppression

Some young prisoners [54] show persistent trauma, with responses such as emotional suppression, cognitive distancing, and internal reframing of experiences (trauma reframing).

3.6. Factors That Strengthen Coping Strategies

3.6.1. Social Support

The most consistent factor that strengthens coping strategies is social support, especially from family and friends [25, 56]. Stability in emotional and instrumental support helps improve mental health significantly.

3.6.2. Spirituality and Religious Practice

Spirituality and religious activities (e.g., worship, metaphysical meaning) have been found to strongly reinforce positive coping, particularly in female and older populations [45, 57, 58].

3.6.3. Rational and Problem-Focused Coping

Strategies such as problem solving, planning, and actively seeking support are associated with reduced distress and improved quality of life [28, 43, 52, 57].

3.6.4. Environmental Factors and Institutional Support

Factors such as access to rehabilitation programs, supportive prison climate, prison type (open vs. high-security), and involvement in educational activities also strengthen healthy coping [50, 59].

3.6.5. Resilience and Positive Mindset

Psychological resilience, driven by positive thinking, goal setting, and self-awareness, is essential in shaping adaptive responses [45, 49, 50].

Based on these reinforcing factors, they can be grouped as follows in a summary Table 3.

From the table, it can be seen that the factors that provide psychological strengthening are family support and well-organized reintegration regulations. Strong family support and social integration play a significant role in reinforcing prisoners' psychological well-being [60]. Furthermore, religious support provided within the prison context enhances both social and emotional support, thereby ameliorating feelings of isolation resulting from separation from family members [61]. Consequently, a surrogate familial network emerges within the institutional setting, reinforcing interpersonal relationships among prisoners and facilitating adaptive responses to the depressive experiences induced by incarceration-related circumstances [62].

4. CONCLUSION OF FINDINGS

The present scoping review identified a wide range of coping strategies employed by incarcerated and formerly incarcerated individuals. The findings are thematically categorized into four major domains:

4.1. Emotion-Focused and Avoidance Coping Strategies

A substantial number of studies highlighted the predominance of emotion-focused and avoidance coping strategies among prisoners, especially during early incarceration or under psychological strain ([41, 43, 59, 47]). These strategies, including emotional suppression, denial, withdrawal, and substance use, were consistently associated with increased psychological distress, anxiety, and depression. For instance, Adhikari and Das [51] reported that a majority of inmates relied on low-approach and high-avoidance coping, correlating with elevated levels of stress and poor adjustment. Similarly, O’Rockey observed that young male prisoners often responded to trauma with emotional detachment and cognitive suppression, reinforcing maladaptive coping patterns.

4.2. Rational and Problem-Focused Coping

Conversely, rational and problem-solving coping styles were linked with improved psychological outcomes. Ireland et al. [44] found that juvenile offenders who employed rational coping reported lower distress levels compared to those relying on emotional strategies. Reed et al. [59] further demonstrated that inmates in open prison environments with access to social support and vocational programs were more likely to engage in constructive, goal-oriented coping. Studies by Skowroński & Talik [46] and Luke et al. [53] confirmed that task-focused strategies such as active coping, planning, and help-seeking contributed to better quality of life and lower distress symptoms.

4.3. Spiritual Coping and Meaning-Making

Spiritual coping emerged as a salient mechanism for managing stress and cultivating resilience. Studies conducted in Indonesia, the Philippines, and the US [27, 25, 58] emphasized that religious engagement, prayer, and finding meaning in adversity helped prisoners reframe their incarceration experience. These strategies not only supported emotional regulation but also instilled a sense of hope and existential coherence. Walker [50] noted that spirituality, coupled with structured reentry programs, enhanced psychological readiness for reintegration.

4.4. Demographic Differences in Coping (Youth, Elderly, Female Inmates)

Coping strategies varied notably across demographic groups. Young offenders tended to rely on emotional and detached coping, resulting in higher vulnerability to psychological distress [43, 54]. In contrast, older inmates preferred acceptance, withdrawal, and introspective practices, reflecting age-related adaptation mechanisms [58]. Female inmates frequently employed emotion-focused and spiritual coping, often shaped by familial separation and gender-specific stressors [27, 25, 63]. Additionally, it was highlighted that prison officers, though not inmates, used peer-based support such as “talking to colleagues” as an emotional regulation strategy, showing the broader relevance of social coping mechanisms within carceral systems.

5. DISCUSSION

The results of the analysis of 20 studies show that prisoners exhibit various psychological responses indicating distress, such as depression, anxiety, stress, adjustment difficulties, and trauma. These responses emerge not only in the early stages of detention but also persist post-release, manifesting as reintegration challenges. The coping strategies employed are highly diverse, ranging from adaptive responses such as problem-focused coping, cognitive reframing, and resilience-building, to maladaptive behaviors like avoidance, emotional suppression, and substance abuse.

Among personality traits, neuroticism had the strongest direct and indirect association with anxiety disorders through the mediating roles of low self-esteem and insufficient social support. Conversely, traits such as agreeableness and conscientiousness were negatively correlated with anxiety symptoms, suggesting that certain dispositional factors can serve as protective resources when facing incarceration-related stressors [64]. Emotion-focused coping has been consistently linked with heightened psychological distress [41, 43, 53], reinforcing its classification as a maladaptive strategy when employed over extended periods or in response to uncontrollable stressors. This finding aligns with the transactional model of stress by Lazarus and Folkman, which postulates that individuals tend to adopt emotion-focused strategies when stressors are perceived as unmodifiable. In contrast, rational or problem-focused coping appears more effective in reducing symptoms of distress and enhancing adjustment outcomes, particularly when inmates are embedded in supportive environments [46, 59]. These strategies reflect proactive engagement with the stressor and align with the theoretical assumption that control appraisal mediates the choice of coping style. For instance, the presence of institutional support systems, such as counseling, education, and structured reentry preparation, was found to facilitate the use of adaptive coping mechanisms.

An interesting nuance in the findings is the relative effectiveness of detached coping among adolescent inmates [42], which may reflect developmental differences in emotional regulation and autonomy needs. Moreover, spiritual coping and cognitive reframing emerged as central to meaning-making and psychological resilience across diverse cultural settings, particularly in Southeast Asia and the Middle East [45, 54, 27]. These findings underscore the contextual nature of coping and highlight the relevance of cultural and religious resources in shaping psychological adaptation behind bars. Several studies also noted gender and age-specific coping patterns. Female prisoners were more likely to use emotion-focused and spirituality-based coping [25, 27], often linked to their roles in family systems and experiences of relational loss. In contrast, male inmates, especially those in maximum-security settings, tended toward aggressive and avoidant strategies [65], suggesting the need for gender-sensitive and violence-informed interventions.

These findings are consistent with past literature that emphasizes the pivotal role of adaptive coping in maintaining psychological well-being during incarceration [66]. However, our review expands this perspective by systematically mapping how personality traits, sentence characteristics, and cultural context interact with coping outcomes. For example, the variability in the effectiveness of social support, when derived from family, but mixed when sourced from peers, illustrates the complexity of interpersonal dynamics within prison environments.

This study recommends the development of integrated rehabilitation programs that emphasize not only skill-building (e.g.,problem-solving training) but also psychoeducational modules on emotional awareness, resilience, and spiritual engagement. Interventions such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), emotion regulation training, group counseling, and religious mentoring can foster healthier coping repertoires. Moreover, structured programs like vocational education, spiritual groups, and family visitation policies have been shown to enhance prisoners’ adaptive functioning both during and after incarceration [47, 67]. From a theoretical standpoint, these findings validate the transactional model of stress and coping as a useful lens for understanding inmate behavior. However, they also suggest that resilience theory [68] and social support theory [69] offer complementary frameworks to capture the ecological and cultural dimensions of prison life. For instance, coping success was not merely a function of internal traits or isolated skills, but also depended on external supports and perceived meaning, highlighting the need for systemic interventions.

From an academic standpoint, this review provides an integrative typology of coping mechanisms among incarcerated populations, structured thematically and enriched by cultural and demographic lenses. The study contributes to the growing literature on prison mental health by identifying key moderating variables, including prison type, sentence duration, and inmate background, that influence coping effectiveness. Practically, the findings have immediate relevance for prison administrators, psychologists, and policymakers. Tailored interventions can be designed to address the distinct needs of different inmate groups, integrating spiritual and cultural elements where relevant. For example, incorporating chaplaincy services, peer mentoring, and community engagement can strengthen psychological outcomes and reduce recidivism risks.

These findings corroborate prior studies. Future research should prioritize longitudinal and mixed-method studies to trace the trajectory of coping strategies from entry into prison through post-release reintegration. Such an approach would clarify how coping styles evolve and how interventions can be timed for maximal impact. It is also important to explore spiritual and cognitive-based interventions further, particularly in under-researched populations such as juvenile inmates, female prisoners, and long-term detainees.

Cross-cultural and institutional comparative studies are likewise recommended, as they can illuminate how legal systems, religious values, and prison structures affect coping. Understanding these contextual influences can inform policy frameworks that prioritize rehabilitative rather than punitive models. Ultimately, such evidence can guide the development of evidence-based, culturally grounded correctional policies that center on inmate well-being, social justice, and successful societal reintegration. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the first scoping reviews to systematically integrate personality, cultural, and institutional variables in the analysis of coping strategies among incarcerated populations.

CONCLUSION

Summary of Key Findings

This scoping review of 20 articles highlights that prisoners and former prisoners experience various psychological challenges, with outcomes largely influenced by their coping strategies and the availability of social and institutional support. Maladaptive coping strategies, such as withdrawal, repression, and substance abuse, are consistently associated with heightened psychological distress and difficulties in post-release reintegration. Conversely, adaptive strategies, including problem-focused coping, cognitive reframing, and spiritual practices, foster resilience and psychological well-being. Supportive factors such as family involvement, peer support, counseling services, educational programs, and a positive prison climate play a crucial role in reinforcing constructive coping.

Theoretical and Practical Significance

These findings contribute to the theoretical understanding of stress and coping, particularly in correctional settings, by integrating personality traits, cultural influences, and institutional variables into one coherent model. Practically, the study provides valuable insights for prison administrators, counselors, and policymakers to develop targeted, evidence-based interventions that are culturally sensitive and responsive to inmates’ psychological needs. The results also support the transactional model of stress and resilience theory as robust frameworks for designing correctional mental health strategies.

LIMITATIONS

This review is limited by its focus on studies published between 2000 and 2025, potentially overlooking relevant earlier contributions. Additionally, the review does not differentiate findings by criminal offense type or by demographic subgroups of prisoners. The scope is general and may not fully capture the nuanced experiences of specific populations such as juveniles, females, or long-term inmates. Moreover, the review relies on published literature and may be subject to publication bias.

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIONS

Future studies should explore coping strategies among subgroups of incarcerated individuals, including those differentiated by gender, age, crime type, or sentence duration. Longitudinal and mixed-method research is particularly needed to understand how coping mechanisms develop and shift from entry into incarceration through reintegration. Investigating the role of culturally grounded interventions, such as religious mentoring and community engagement, can also shed light on more holistic rehabilitation strategies. Finally, comparative studies across legal systems and prison environments can inform policy models that better support inmate mental health and reduce recidivism.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: E.P.: Conceptualization; T.T.: Methodology; analysis and interpretation of results: MJ; Writing - Reviewing and Editing: WDP; Writing - Original Draft Preparation: WK. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to all those who contributed to the preparation of this article. I am particularly indebted to my Promoter and Co-promoter for their invaluable input, and to Prof. Taufik, Ph.D, and Prof. Eny Purwandari., for their thorough review and comprehensive guidance on scientific writing during the literature review and preliminary stages of my dissertation.