All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Comparative Analysis of Resilience between Technical and Non-Technical Trades in Highly Stressed Workplaces: A Non-experimental Quantitative Modelling Approach

Abstract

Introduction

Resilience is the ability to recover from setbacks and is particularly important in jobs such as security due to the demanding nature of the duties involved. This study focuses on the factors that promote resilience among individuals working in various sectors of the security field, namely the military, police, and private security.

Methods

This study examines the differences in resilience between people employed in technical and non-technical fields. A cross-sectional, non-experimental quantitative design was used, employing stratified sampling and the CD-RISC© for data collection.

Results

In the proposed study, a sample of 400 professionals (200 from non-technical trade and 200 from technical trade) was assessed for resilience across different career domains. The scale used for this is the Connors-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD RISC©). The analysis revealed that professionals in technical trades had a significantly higher resilience index mean rank (M = 64.5, SD = 18.54) compared to non-technical professionals (M = 59.86, SD = 19.42).

Discussion

The research shows that people in technical trades have greater resilience compared to their counterparts in non-technical roles within the security domain. This may be attributed to the more structured nature of technical occupations, which promote problem-solving, routine, and psychological stability. Moreover, individuals in technical roles tend to be more meaningful and optimistic. These findings emphasize the need to develop tailor-made resilience training for each role. Targeted strategies can be developed to improve overall well-being and performance across varying occupations.

Conclusion

These findings suggest that highly structured technical trades may foster greater psychological resilience due to their problem-solving requirements. This study highlights the necessity of developing specialized, organizationally focused training for resilience and mental health interventions in both professional sectors. Knowing these differences will allow organizations to create more effective support mechanisms to improve workers' well-being and productivity.

1. INTRODUCTION

The capability of an individual to recover and perform successfully under challenging situations, such as work-related stress, uncertainty, and adversity, is an important aspect of resilience. Previous findings have indicated that resilient employees demonstrate greater job satisfaction, lower levels of burnout, and increased productivity, which benefits the workforce [1, 2]. In security services, healthcare, first responder roles, and technical trades, where there are constant active challenges, greater resilience is essential. Individuals in these sectors deal with high levels of unpredictability and demand. Organizations that implement targeted training and policies aimed at cultivating resilience are better positioned to enhance engagement and adaptability among their employees in the long term [3].

In the field of Security services, not everyone is engaged in field duties. These workplaces are generally grouped into Technical and Non-Technical trades, with each classification having its own job requirements and stressors. Technical trades include specialized skills such as computer operators, teleoperators, mechanics, and technical equipment handlers. These profiles need accuracy, logical analysis, and problem-solving abilities within stringent timelines. Employees in technical professions often face task complexity, operational constraints, and deadlines that require high-level adaptability and resilience [4]. Non-technical trades, such as administration, management, logistics staff, and human resources, require communication, decision-making, and basic emotional skills. Although non-technical professionals are not necessarily in high-pressure, physical, or technical environments, they still experience significant stress related to managing people, organizational conflict, and service pressures [5].

Despite comprehensive research on workplace resilience, a gap persists in fundamental comparative studies examining differences in resilience between technical and non-technical trade occupations in high-stress professions. Resilience has been studied in specific occupational groups such as healthcare, law enforcement, and the IT industry [6]. However, there is scant literature examining how trade categories differ in their resilience traits.

Most previous research has focused on building resilience at the individual level, overlooking organizational approaches that may be designed for specific professions [7]. Moreover, earlier studies tend to focus on resilience as a one-dimensional concept, disregarding other components such as cognitive flexibility within technical roles and emotional agility in non-technical roles. Closing this identified gap will allow organizations to create targeted strategies that provide proactive resilience-building resources tailor-made for the demands of both technical and non-technical trades [8].

1.1. Review of Literature

Physical and psychological hard work is routine for security service personnel, including military police and firefighters. Such duties involve making decisions in high-risk environments, being away from one’s family for extended periods, and experiencing intense levels of physical and emotional strain and stress [9]. In high-stress conditions, the ability to recover from adverse life events is crucial for maintaining an individual's mental and emotional health [5]. Earlier research has noted that, although much is known about the concept of resilience in other populations, studies on resilience among security service personnel are relatively scarce. Recent research demonstrates how organizational responsibility and CSR contribute to building resilience while reducing burnout, aligning with the UN Sustainable Development Goals [10]. The assumption of similar resilience dimensions between technical and non-technical trades arises from their shared organizational environment and the standardized resilience-building initiatives present throughout security services. Studies conducted in military and police settings indicate that institutional training programs, when combined with organizational culture, can significantly impact psychological resilience across different roles. For example, the U.S. Army's Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness (CSF2) program [11] implements standardized resilience training for all service members, fostering organizational resilience behaviors rather than role-specific ones. Similarly, research on police officer resilience training shows equal improvements in stress management and coping abilities among personnel, regardless of position or duties. The standardized training and uniform stress exposure in uniformed services likely create conditions that generate comparable resilience levels between technical and non-technical roles.

Resilience is one of the psychological attributes that is critical for a human being. This includes members of armed forces, emergency workers: medics, firefighters, and police, etc., who are at high risk of facing physical threat, psychological stress, or even death. Resilience appears to be relative and context-dependent, shaped by repeated exposure to stressful encounters, such as recovering from a disaster. It is through this process that resilience becomes enduring, especially among individuals in the forces, in terms of security, protection, and response to threats [12]. For security personnel, soldiers, and police, an individual's mental capability is of utmost importance, as it directly affects the performance outcomes of armed forces and law enforcement agencies in threat mitigation, crisis management, and emergency response [13].

According to published studies, resilience consists of multiple factors, including personal characteristics such as optimism, self-efficacy, and emotional control, as well as external resources like social support and organizational environment [14]. Resilience-oriented training programs enable practitioners in the security field to better manage stress and trauma, thereby enhancing their coping mechanisms [15]. Furthermore, the ability to carry out professional duties effectively contributes not only to overall psychological health but also to increased resilience and reduced incidence of burnout and stress-related ailments [15]. The ability to adapt and recover from adversity is generally what resilience refers to in Security Service personnel. For military personnel, police officers, private security personnel, and first responders, this trait is essential for managing highly stressful, life-threatening circumstances. They often maintain resilience through training, discipline, and strong peer support, which help them face trauma, maintain focus under pressure, and continue performing their duties effectively [14]. Resilience is a fundamental attribute that serves as a bedrock for soldiers, shaping their capacity to navigate the multifaceted challenges inherent in military life. Whether facing the trials of combat, extended postings, or the stress of separation from loved ones, soldiers encounter situations that continuously test their resilience. Security service personnel, by virtue of their career, face remarkable levels of strain and adversity. The extreme level of training, facing the odds of nature and the battlefield, with its inherent risks and uncertainties, serves as the testing floor for his/her resilience. In particular, in healthcare work, resilience is understood as emotional regulation, social support, and professional self-efficacy [16]. In the domain of education, it is awareness towards job satisfaction and the management of work-related pressures [17].

When discussing technical and non-technical trades in security services, both share some commonalities. For example, both trade’s personnel in security service have been trained to face emotional, environmental, and physical challenges. They often experience prolonged separation from loved ones due to duties, trade-related obligations, and responsibilities. Within a security service, each trade has its own distinct training procedures that focus on its specific duties and responsibilities. In technical trades, training is highly specialized for operators of surveillance systems, computer operators, tele-operators, technical equipment handlers, and communications technicians. These professions involve proficient handling of technologies, as well as encryption, threat detection, and precise problem-solving. Technological advancements require constant updates to training programs to address emerging security concerns. In contrast, non-technical trades, which include security guards, human resource managers, administration, and logistics staff, are trained to improve physical endurance, perform drills, manage crises, and develop social aptitude. Their training covers self-defense strategies, emergency response procedures, HR management, supply chain handling, and maintaining public safety and order. Both groups are essential for overall security, but each makes a unique contribution. Relying on expertise in digital and electronic systems, information technologies is the domain of technical professionals. The other, non-technical personnel, are ground duty personnel to provide physical security and shift work. Although both trades are fundamentally different, security is only guaranteed when there is collaboration between them. However, there are only a few studies that compare and analyze the resilience of Technical and Non-Technical professionals in such high-stress jobs, including the military, police, and private security forces, which this study will seek to do.

1.2. Hypothesis

H1: Employees in technical and non-technical trades exhibit similar levels of hardiness within security services. As a form of personality associated with stress resistance, hardiness includes commitment, control, and challenge. This theory assumes that all security staff members, regardless of their position, face similar environmental stressors.

H2: Technical and non-technical trades demonstrate the same level of coping strategies. In this scenario, the assumption is that both sides of a security services organizational structure, whether hands-on, technical, or support, use similar coping strategies to manage stress and organizational expectations. Emotional coping strategies could include planning and emotional regulation.

H3: No difference in levels of adaptability and flexibility between technical and non-technical trades. In dynamic work environments, such as within security services, adaptability and flexibility are two critical driving attributes. This hypothesis states that all technical and non-technical staff possess comparable capability to adapt to shifts in protocols and strategies, or to learn new steps as per the requirements of their designations.

H4: No difference in levels of meaningfulness and purpose between technical and non-technical trades. According to the psychological construct this hypothesis aims to test, there exists a level of connection or attachment that employees feel towards the work they do, with both technical and non-technical workers sharing equally in their perception of the significance and value of their efforts.

H5: Both technical and non-technical trades have the same level of logical problem-solving and innovative approaches. Decision-making, as well as exercising as deemed necessary within the security services field, requires problem-solving and innovative skills to be at the forefront.

The basis for H1–H5 is that technical and non-technical security personnel work in the same organizational culture and receive resilience-oriented training and experience similar stressors, including long work hours, security threats, and high accountability. Research shows that institutional ethos and standardized training programs yield similar resilience attributes across occupational groups [3]. The assumptions underlying H1–H5 stem from the fact that both technical and non-technical security personnel operate within the same organizational culture, undergo resilience-oriented training, and face overlapping stressors, such as long work hours, security threats, and high accountability. Previous studies suggest that shared institutional ethos and standardized training programs often lead to similarity in certain resilience attributes across occupational categories [3].

H6: Technical trade personnel and non-technical personnel have the same level of emotion regulation and cognitive control. Emotion regulation, as defined here, is the ability to control one’s emotional reaction, while cognitive control encompasses the ability to focus, make decisions, and react under stress. This assumption postulates that the emotional self-discipline and mental self-control resulting from the training and job requirements in the security services are uniform across both technical and non-technical personnel, enabling all to perform efficiently even in highly emotional or critical situations.

H7: Technical trade and non-technical personnel have similar levels of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is defined as the belief an individual has regarding their ability to accomplish a specific goal or manage conflict. It is assumed that both technical and non-technical staff of the security services possess an equally high sense of self-efficacy.

The reviewer notes that the research lacks a theoretical framework. The study now has an explicit theoretical framework based on Fletcher and Sarkar [1] in 2013's integrated framework for psychological resilience and on Robertson, Cooper, Sarkar, and Curran’s [3] Workplace Resilience Framework. These models view resilience as a construct that includes personality traits, along with organizational and environmental factors, that enable positive adaptation under stress.

H1 examines hardiness as a personality trait that includes commitment, control, and challenge, and has been shown to protect against stress in high-risk professions [12, 18].

H2 addresses coping strategies that include both problem-focused and emotion-focused coping, as defined in workplace resilience theory [9, 15].

H3 investigates adaptability and flexibility, the ability to adapt to changing demands, which is a key component of occupational resilience [6, 4].

H4 investigates meaningfulness and purpose, which drive motivation and persistence in difficult situations [7, 17].

H5 tests optimism, a generalized positive outcome expectation, which is recognized as a protective factor in psychological capital [2, 10].

H6 looks at emotion regulation and cognitive control, the ability to stay calm and focused in intense situations [14, 19].

H7 evaluates self-efficacy, the belief in one’s ability to reach goals and handle difficulties [20, 21].

2. METHODOLOGY

The methodology adopted for this research on resilience among security service personnel was a cross-sectional, non-experimental quantitative design. The stratified sampling technique was used to ensure that samples from different ranks, ages, and roles within the security service were included. This design was chosen because it was appropriate for collecting data at a single point in time, without manipulating any variables, and for analyzing existing conditions and relationships among technical and non-technical trades. The focus of this research was to understand the psychological construct of resilience and its sub-attributes among technical and non-technical trades in high-stress jobs such as security services. The study employed a quantitative method that involved adopting the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) for numerical data collection. This approach allowed for the objective assessment and statistical computation of participants’ resilience levels. The measuring scale ensured not only consistency but also reliability in measuring resilience, making it possible to conduct analyses across different settings and occupations.

As this was a cross-sectional study, data were collected from participants at a single point in time. This design was appropriate for assessing the actual level of resilience of security service personnel, providing an overview of resilience across varied age and employment categories. It was also suitable for determining resilience and its predictors in relation to age, years of service, and specific functions performed by an individual (technical or non-technical). Correlational analysis was employed to determine the relationship between both trades regarding resilience and its sub-attributes.

The Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-25) demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach’s α = .91). The CD-RISC-25 has shown strong construct validity and reliability across high-stress job profiles, supporting its suitability for occupational research in high-stress environments [8, 22-24].

2.1. Study Limitations

Although this research sheds light on the differences in resilience among technical and non-technical security trades with respect to the security services industry, there are some vital limitations to consider:

- Gender Homogeneity: The sample consisted solely of male participants. This restricts the applicability of the results to female employees or gender-diverse individuals. It suggests the need for more balanced studies that would allow for an understanding of resilience across all demographics.

- Cross-Sectional Design: With this study’s cross-sectional design, resilience could only be captured as a snapshot at a given moment in time. This approach does not allow for observing the extent to which resilience could be nurtured with training and experience, or how it evolves with changes in the workplace. More longitudinal work is required to deepen the understanding of resilience.

- Self-Reported Measures: Collection through self-reported questionnaires, particularly those purporting social desirability or inaccurate self-assessment, may compromise the data’s objectivity. The reliability of the findings could be improved by combining self-reported data with behavioral assessments or supervisor evaluations, despite the CD-RISC-25 being a validated instrument.

- Unmeasured Confounding Variables: The analysis did not account for education, organizational culture, leadership, or previous trauma, which are typically controlled for. These factors might also impact resilience and need to be addressed in future studies.

2.2. Search Strategy

An optimized search was conducted to collect studies and models on psychological resilience, occupational stress, and differences by trade within occupational settings. The goal was to inform the study design, determine which tools to use for data collection, and align the instruments with the intended outcomes. The databases searched included PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, Google Scholar, ScienceDirect, and JSTOR.

2.3. Searched Terms and Keywords

The following combinations of predefined words were utilized: “Resilience AND workplace”, “Occupational stress AND resilience”, “Technical trades AND psychological resilience”, “Non-technical roles AND coping strategies”, “Security personnel AND adaptability”, “Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale OR CD-RISC”, “Hardiness AND occupational psychology,” and “Workplace wellbeing AND trade differences.”

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

- Article selection is limited to peer-reviewed publications released within the years 2000 to 2023. Mostly covering this topic in the past decade.

- Corresponding studies are required to be published in English.

- Research conducted on areas focused on resilience in the occupational environment that are high in stress.

- Corresponding studies incorporate either technical or non-technical roles.

- Publications discussing the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) or other comparable, validated resilience assessment tools are included.

- Literature examining the field of security services, military, police, firefighters, emergency responders, or similar occupations with high-stress work environments.

2.5. Exclusion Criteria

- Publications in languages other than English are excluded.

- Research involving other settings that are not high-stress workplaces is excluded.

- Publications that do not contain empirical evidence, such as editorials or commentaries, are excluded.

- Studies focusing solely on females, the elderly, or children.

- Research unrelated to constructs such as psychological resilience, hardiness, coping, or adaptability.

2.6. Selection Process

The initial step in this part of the process was eliminating remaining duplicates, after which titles and abstracts were screened for relevant content. Full-text examinations were then performed on all studies that met the inclusion criteria. The theoretical framework and discussion of results were based on approximately 30 publications that were selected and referenced.

2.7. Participants

This study included 400 male respondents: 200 from the technical trade category and 200 from the non-technical trade category within the Security Service Profession. The participants came from different positions within the security service, covering a wide range of initial training, job functions, and operational duties. Participants were selected through stratified sampling to ensure all roles, ranks, and service histories were represented in the sample. The research employed a stratified probability sampling design. The research established organization type (military, private security) and trade (technical vs non-technical) as mandatory strata. The research team established additional strata for workforce characteristics, including rank bands (junior/middle/senior) and age bands (19–25, 26–35, 36–45, ≥51) and years of service (0–5, 6–10, 11–15, >15) to enhance balance. The research team used their domain expertise to establish strata, then consulted organizational points of contact to validate strata that matched official HR classifications. The sampling frames originated from each organization's active personnel rosters. Participants were randomly selected from each populated stratum using a computer-based random-number generator with no replacement. The organization-level sample sizes received proportional-to-size allocation while maintaining equal trade totals of 200 participants for technical and non-technical groups to maximize precision for the main between-trade analyses.

Participants' ages spanned from 19 to 51 years, with a mean of approximately 31.49 years (SD = 7.71). The selection of a sample comprising only male participants stemmed from the demographic composition of the security institutions surveyed, where male employees constitute the majority.

A sample size of 400 was set to provide reliable statistical power to detect medium effect sizes (d ≈ 0.5) at the 95% confidence level and 0.80 power for two-tailed independent-group comparisons.

2.8. Data Collection

For the empirical component of the study:

Responses from participants were collected using a structured questionnaire. Psychological resilience was measured using the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-25) Connor & Davidson [22]. The questionnaire also included items to collect demographic information (age, years of service, trade category). All responses were anonymized and numerically coded to ensure confidentiality and facilitate statistical analysis.

2.9. Data Analysis

The following statistical methods were conducted using the SPSS tool:

- Descriptive Analysis: Each group’s resilience scores, age, and years of service were calculated, along with the relevant mean, standard deviation, skewness, and median values.

- Inferential Analysis: Given the non-parametric distribution of resilience scores, the difference between technical and non-technical personnel was analyzed with an Independent-Samples Mann-Whitney U Test.

- Subscale Comparisons: Nonparametric group-comparison tests were used to examine resilience sub-attributes (hardiness, coping, adaptability) separately.

- Correlation Analysis: The sub-attributes of resilience were examined among the entire sample. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to determine the interdependence of these sub-attributes. A significance level of 0.01 was applied.

The Mann–Whitney U Test has been widely applied in occupational research; for instance [25], employed it to examine group-level differences in their study on the designer’s role in workplace health and safety in the construction industry. These procedures have greatly strengthened the methodology and interpretation of variation in psychological resilience among the two occupational groups of trades.

2.10. Connor-davidson Resilience Scale 25 (CD-RISC-25)

The CD-RISC-25 consists of 25 self-reported items, each rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“Not true at all”) to 4 (“True nearly all of the time”). The resulting score provides a differentiated understanding of resilience in individuals, establishing not merely an overall measure of resilience but also helping reveal specific strengths or gaps. The concepts underlying a tool such as the CD-RISC-25 are derived from facets of psychological resilience, such as hardiness, self-efficacy, optimism, and purpose [22]. For security service personnel, resilience is developed and sustained through hardiness, coping skills, adaptability, meaningfulness, emotional and cognitive self-regulation, and self-efficacy. It becomes apparent that these attributes influence the professionals in designing security programs that remain result-oriented, effective, and supportive.

2.11. Hardiness

Hardiness is a key trait that enables a person to remain committed, perceive a sense of control, and view every challenge as an opportunity for growth. Security service personnel typically work in high-risk environments, and depending on their level of hardiness, they are able to stay calm and focused on the task. Studies have shown that hardiness reduces stress responses and enhances decision-making during stressful situations [18].

2.12. Coping

Coping is one of the important strategies used to moderate stress and achieve psychological balance. Security Service personnel face and deal with traumatic events, conflicts, stressful situations, and violence, which require efficient coping strategies. Effective emotion-focused techniques like relaxation and mindfulness help in reducing anxiety and emotional exhaustion.

2.13. Flexibility and Adaptability

Flexibility and adaptability are crucial for security service professionals as they deal with rapid changes that require immediate action. Security personnel face the challenges of active violence, emergency evacuations, and nuanced social interactions. All of these demand sudden changes in behavior, thoughts, emotions, and overall self-regulation.

2.14. Purpose and Meaningfulness

Purpose and meaningfulness as attributes are especially relevant for mental health and well-being, making them even more salient for people in high-risk occupations. For security professionals, meaning largely stems from protecting people, maintaining peace, taking risks, and being part of positive changes in society.

The ability to manage challenges on both an emotional and cognitive level is essential for security professionals who work in high-risk situations, requiring them to control their emotions and remain clear-headed. Effective emotion management strategies, such as cognitive appraisal, mindfulness, and deliberate deep-breathing techniques, enable individuals to suppress panic and make rational decisions during crises. Security officers are also trained to manage disruptive thoughts, traumatic memories, or anxiety concerning persistent danger through cognitive regulation [19].

2.15. Self-efficacy

Self-efficacy, the ability to believe in oneself that they can achieve a particular result, is a notable construct when thinking about resilience among security professionals. Comprehensive studies show that high self-efficacy increases the likelihood of staying calm during distressing situations, enhances performance in critical scenarios, and facilitates quick recovery from setbacks [21].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Data Analysis

While analyzing the data, a total of 400 samples, including 200 non-technical security trades personnel and 200 technical trades security service personnel, were analyzed. No missing values were reported, and the data used for the descriptive statistics of Resilience, Age, and Service were drawn from 400 participants. As shown in Table 1, a striking finding is the difference in resilience, with technical trades scoring higher than non-technical trades (M = 64.52, SD = 18.54 vs. M = 59.86, SD = 19.42). The resilience scores reported in Table 2 (69.00 for technical vs. 65.50 for non-technical) further support this trend, indicating that technical personnel tend to be more resilient. Both groups exhibit negatively skewed distributions of resilience scores, suggesting that most individuals tend to score higher than the average. However, the technical group shows a more pronounced skew toward higher values (-0.847) compared to the non-technical group. In terms of analyzing Years of Service, non-technical trades tend to have a slightly higher average value (M = 11.96, SD = 7.38) than technical trades. This is also true for medians (non-technical: 14.00; technical: 12.00). The distributions of both groups are also negatively skewed, though Non-Technical has a stronger skew (-0.431), indicating that more people in this group have a longer duration of service.

| Trade | Resilience | Service | Age | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Technical Trade | Mean | 59.8600 | 11.9550 | 31.7550 |

| N | 200 | 200 | 200 | |

| Std. Deviation | 19.42336 | 7.38006 | 7.82567 | |

| Median | 65.5000 | 14.0000 | 33.0000 | |

| Minimum | 20.00 | 1.00 | 19.00 | |

| Maximum | 93.00 | 20.00 | 47.00 | |

| Skewness | -0.572 | -0.431 | -0.291 | |

| Technical Trade | Mean | 64.5150 | 10.9700 | 31.2300 |

| N | 200 | 200 | 200 | |

| Std. Deviation | 18.53558 | 7.01320 | 7.60105 | |

| Median | 69.0000 | 12.0000 | 31.0000 | |

| Minimum | 20.00 | 1.00 | 19.00 | |

| Maximum | 93.00 | 20.00 | 51.00 | |

| Skewness | -0.847 | -0.152 | 0.141 | |

| Total | Mean | 62.1875 | 11.4625 | 31.4925 |

| N | 400 | 400 | 400 | |

| Std. Deviation | 19.10353 | 7.20683 | 7.70899 | |

| Median | 67.0000 | 13.0000 | 32.0000 | |

| Minimum | 20.00 | 1.00 | 19.00 | |

| Maximum | 93.00 | 20.00 | 51.00 | |

| Skewness | -0.699 | -0.289 | -0.081 | |

| Null Hypothesis | Test | Sig.a,b | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|

| The distribution of Resilience is the same across Technical and Non-Technical trades. | Independent-Samples Mann-Whitney U Test | 0.014 | Reject the null hypothesis. |

Note: a. The significance level is .050.

b. Asymptotic significance is displayed.

By age, the means are quite similar: 31.76 years (SD = 7.83) for non-technical personnel and 31.23 years (SD = 7.60) for technical personnel. Their medians are also closely aligned (33.00 and 31.00, respectively), suggesting that there is no considerable difference in the ages across the two categories, and mostly the age is around 30s. Shifting to the entire sample (N = 400), the average resilience score is 62.19 (SD = 19.10) and has a moderate negative skewness of -0.699, indicating that high resilience scores are more common across the population.

On scrutinizing resilience factors within both technical and non-technical disciplines reveals important aspects regarding their psychological strengths and resilience. The scale used here, CD-RISC-25, consists of statements describing different facets of resilience. The scale is sub divided into other items which measure hardiness (commitment/challenge/control) (measuring 5, 10, 11, 12, 22, 23, 24), coping (2, 7, 13, 15, 18), adaptability/flexibility (measuring 1, 4, 8), meaningfulness/purpose (measuring 3, 9, 20, 21), optimism (measuring 6, 16), regulation of emotion and cognition (measuring 14, 19), and self-efficacy (measuring 17, 25). All these attributes shed light on the six aspects of Hardiness, Coping, Adaptability/Flexibility, Meaningfulness/Purpose, Optimism, Emotion, Cognition, and Self-Efficacy.

Table 3 depicts results showing that, compared to non-technical trades, all technical trades are consistently more resilient.

| Total N | 400.000 |

| Mann-Whitney U | 22833.000 |

| Wilcoxon W | 42933.000 |

| Test Statistic | 22833.000 |

| Standard Error | 1155.856 |

| Standardized Test Statistic | 02.451 |

| Asymptotic Sig. (2-sided test) | 0.014 |

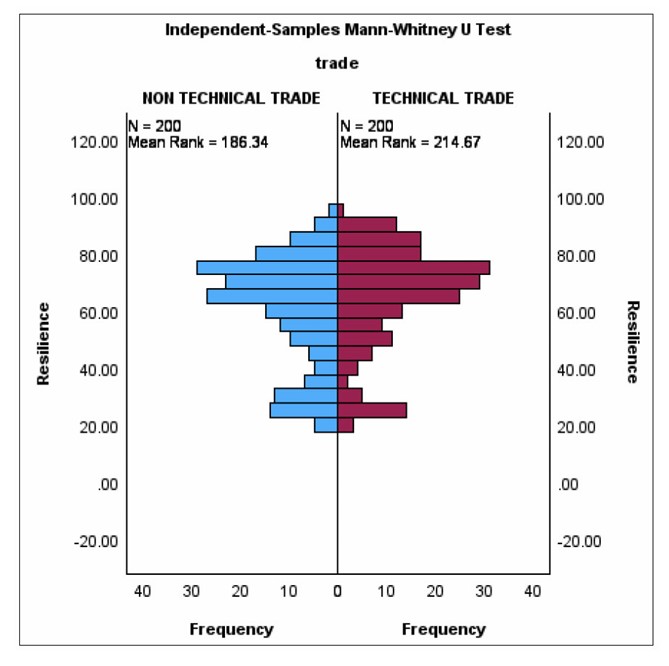

The obtained results, as indicated in Figure 1, show a U value of 22,833.00 alongside a p-value of 0.014, which is lower than the significance level of 0.05. Therefore, the null hypothesis will be rejected, as there is indeed a difference in resilience scores between the two groups, and it is statistically significant. Participants in technical trades had a mean rank of 214.67, and participants in non-technical trades had a mean rank of 186.34. Hence, it can be inferred that technical trade individuals exhibit greater resilience than non-technical trade individuals. The symmetrical bar graph posted above shows the relative distribution of higher scores among the technical trade group, making the difference apparent. With a standard error of 1155.856, the standardized value for the tested hypothesis was 2.451, indicating that the difference between the two groups is not only profound but also statistically significant. It can be concluded that the type of trade a person is in and the associated tasks can have substantial impacts on a person’s resilience due to the problem-solving challenges, the nature of the training required for the role, or even the nature of the role itself.

Mann Whitney U test between non-technical and technical trade.

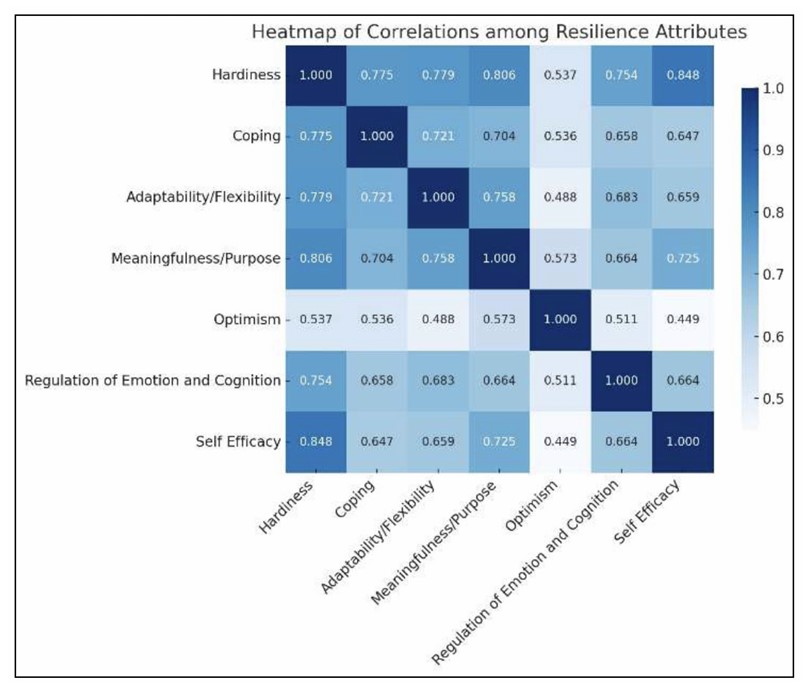

3.2. Correlation Analysis

Analyzing the correlation of psychological resilience attributes of hardiness, coping, adaptability, meaningfulness, optimism, emotional self-regulation, and self-efficacy provides crucial insights into the relationships of traits that form the psychological security personnel possess. According to the analysis, all correlations are positive and statistically significant at the 0.01 level, a common benchmark in the social sciences, and, in many cases, the strength of these relationships is quite high. This suggests that there is a considerable, cohesive, or reciprocal linkage among resilience factors that support one another. More importantly, as shown in Figure 2, the correlation between hardiness and self-efficacy was reported as the strongest (r = 0.848), indicating that those who are self-identified as psychosocially hardy, that is, people who claim to endure and indeed thrive in situations of difficulties or psychologically strenuous conditions, have stronger beliefs regarding their ability to control and manage undesirable circumstances. For the study, it has already been shown that individuals in Technical trades display a relatively higher level of hardiness than their counterparts. This means that increasing personnel’s hardiness could add value, enhance emotional wellness, and performance under stress.

Heatmap of correlation among sub attributes.

Table 4 clarifies that resilient people show great purpose and flexibility in their work, which explains the correlations of hardiness with adaptability (0.806) and purposefulness (0.779). Coping strategies for dealing with stress align with hardiness (0.775) and adaptability (0.721), suggesting that people who are psychologically hardy also have effective coping strategies to stress and sudden changes.

| - | Null Hypothesis | Test Used | Test Statistic (U) | p-value | Interpretation | Mean Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Technical Trade | Technical Trade | ||||||

| H1 | Employees in technical and non-technical trades exhibit similar levels of hardiness to personnel in security services | Independent- Samples Mann-Whitney U Test | 17080 | 0.011 | Reject the null hypothesis. | 185.9 | 215.10 |

| H2 | Technical and non-technical trades demonstrate the same level of coping strategies | 16247 | 0.001 | Reject the null hypothesis. | 181.74 | 219.26 | |

| H3 | No difference in levels of adaptability and flexibility between technical and non-technical trades | 17458 | 0.027 | Reject the null hypothesis. | 187.79 | 213.21 | |

| H4 | No difference in levels of meaningfulness and purpose between technical and non-technical trades | 17580 | 0.035 | Reject the null hypothesis. | 188.4 | 212.60 | |

| H5 | Both technical and non-technical trades have the same level of optimism | 17876 | 0.063 | Retain the null hypothesis. | 189.88 | 211.12 | |

| H6 | Technical trade personnel and non-technical personnel have the same level of emotion regulation and cognitive control | 17962 | 0.073 | Retain the null hypothesis. | 190.31 | 210.69 | |

| H7 | Technical trade and non-technical personnel have a similar level of self-efficacy | 17807 | 0.052 | Retain the null hypothesis. | 189.54 | 211.46 | |

Note: Asymptotic significances are displayed.

The significance level is .05.

Overall, these are the findings derived from the developed correlation matrix: the resilience of security service personnel is a multi-layered construct comprising multidimensional forms of psychological strength, emotional control, adaptive coping strategies, and a robust sense of purpose (Table 5). It is apparent that there is a network of traits rather than a single characteristic that enable one to effectively increase psychological resilience and operational effectiveness in the workforce. The multi-strategic approach highlights means to improve operational work effectiveness, aiming to train in developing psychological hardiness, coping and recovery strategies, emotional regulation, self-efficacy, and the self-as-meaning construct, guiding enduring stress and uncertainty required in security services.

| - | Hardiness | Coping | Adaptability/ flexibility | Meaningfulness/ Purpose | Optimism | Regulation of Emotion and Cognition | Self-efficacy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hardiness | Pearson Correlation | 1 | 0.775** | 0.779** | 0.806** | 0.537** | 0.754** | 0.848** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | - | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Coping | Pearson Correlation | 0.775** | 1 | 0.721** | 0.704** | 0.536** | 0.658** | 0.647** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | <0.001 | - | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Adaptability/ flexibility | Pearson Correlation | 0.779** | 0.721** | 1 | 0.758** | 0.488** | 0.683** | 0.659** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | <0.001 | <0.001 | - | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Meaningfulness | Pearson Correlation | 0.806** | 0.704** | 0.758** | 1 | 0.573** | 0.664** | 0.725** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | - | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Optimism | Pearson Correlation | 0.537** | 0.536** | 0.488** | 0.573** | 1 | 0.511** | 0.449** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | - | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Regulation of emotion and cognition | Pearson Correlation | 0.754** | 0.658** | 0.683** | 0.664** | 0.511** | 1 | 0.664** |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | - | <0.001 | |

| Self-efficacy | Pearson Correlation | 0.848** | 0.647** | 0.659** | 0.725** | 0.449** | 0.664** | 1 |

| Sig. (2-tailed) | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | - | |

Note: **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

4. DISCUSSION

The research investigated resilience dimensions between technical and non-technical trades within security services using the CD-RISC-25, a validated measurement instrument.

4.1. Overall Resilience Differences

The Mann–Whitney U test revealed a statistically significant difference in overall resilience, with technical trade personnel earning higher mean ranks compared to non-technical personnel. The theoretical framework suggests that resilience emerges from the combination of individual characteristics and job requirements. Technical employees develop stronger resilience through their work on complex operational tasks that demand problem-solving abilities and precise actions in challenging situations. This research supports the theoretical model, which proposes that resilience arises from the interplay of personal traits and work demands, leading employees to develop adaptive behaviors over time in complex roles with high levels of responsibility [18, 6].

4.2. Hardiness, Coping, Adaptability, and Meaningfulness

Technical trades scored significantly higher than non-technical trades across the four sub-dimensions: hardiness, coping strategies, adaptability/flexibility, and meaningfulness/purpose. The structured, high-accountability technical role environment creates psychological commitment through hardiness while supporting the development of specific coping mechanisms. Technical operational feedback loops, together with procedural learning within these contexts, help develop adaptability and reinforce a sense of purpose among personnel. Workplace resilience, according to Robertson et al. [3], becomes stronger when employees experience control and meaningful tasks while facing appropriate challenges. The combination of structured technical environments with high accountability helps build hardiness and targeted coping abilities, while feedback loops and procedural learning enhance adaptability and strengthen purpose [26].

4.3. Optimism, Emotion Regulation, and Self-Efficacy

The analysis revealed no significant differences in optimism, self-efficacy, or emotion regulation/cognitive control scores between the groups. The equal levels of resilience across both trades result from their shared organizational culture, standardized resilience training programs, and security-related stressors that affect all personnel. According to Fletcher and Sarkar [1], resilience within organizational settings develops fundamental psychological resources in employees across all occupational groups because institutional practices and training methods produce similar levels of resilience. The sub-dimension correlations between hardiness and self-efficacy and hardiness and adaptability support the concept of resilience as a networked multidimensional construct rather than separate traits [26, 15].

4.4. Interconnectedness of Resilience Attributes

The correlation analysis reveals that the resilience sub-dimensions function as interconnected elements, as hardiness shows robust relationships with self-efficacy and adaptability. The concept of resilience demonstrates its role as a complex system of traits that work together as a network rather than independently. People who possess strong hardiness traits demonstrate enhanced coping abilities and better adaptation to operational changes while maintaining their confidence in their work, leading to a reinforcing cycle of resilience.

4.5. Theoretical and Practical Implications

The research provides theoretical support to resilience scholarship by demonstrating how specific occupational roles influence certain resilience dimensions, while others remain unaffected. It offers an enhanced understanding that goes beyond general resilience assessment by identifying specific areas where interventions need to be targeted across different occupational trades.

Non-technical trades should receive resilience training that focuses on developing hardiness, coping flexibility, adaptability, and purpose alignment, as these areas show lower performance. Technical trades, on the other hand, should focus on enhancing optimism and emotional regulation skills, which complement their existing strengths. Tailored resilience intervention programs that address the specific needs of each trade role can improve psychological well-being and operational effectiveness. Accordingly, training for non-technical trades should emphasize hardiness, coping flexibility, adaptability, and purpose alignment, while technical trades should focus on developing optimism and emotion regulation, as supported by workplace and police-training evaluations [27].

CONCLUSION

This research provides new empirical evidence on resilience patterns between technical and non-technical trades in security services, utilizing Fletcher and Sarkar’s [1] conceptual framework and Robertson et al.’s [3] workplace resilience model. Using the validated Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC-25), we found that technical trades exhibit significantly higher resilience levels across the domains of hardiness, coping strategies, adaptability/flexibility, and meaningfulness/purpose.

Multiple factors, including technical demands, procedural requirements, and operational challenges, enable workers to develop specific psychological resources through repeated exposure to complex, high-stakes situations. Security sector professionals demonstrate similar levels of optimism, emotional regulation, and self-efficacy because their organizations maintain standardized training programs, and both groups encounter comparable occupational stressors.

The study results highlight the need for resilience programs tailored to the unique characteristics of each job role. Hardiness development alongside adaptive coping, purpose alignment, and flexibility training would benefit non-technical trades, whereas technical trades should focus on developing optimism and emotional regulation abilities. Implementing such targeted programs can enhance both psychological well-being and operational outcomes, while supporting workforce stability in the long term.

This research is the first to employ the CD-RISC-25 instrument to directly compare resilience across trades in security service workers, establishing a new direction for occupational resilience studies. Future research should adopt longitudinal and mixed-methods approaches, include gender-diverse participants, and examine organizational factors that influence resilience development throughout different career phases. Overall, this study provides both theoretical foundations and practical strategies to strengthen security workforce resilience through occupational role-specific analysis and the application of psychological theory.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: M.N. and A.G.: Study conception and design; M.N.: Data collection; M.N. and checked by A.G.: Analysis and interpretation of results. Both authors have read and incorporated all changes and have agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| CD-RISC | = Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale |

| SD | = Standard Deviation |

| M | = Mean |

| U Test | = Mann-Whitney U Test |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for Social Sciences |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study with human participants was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Board of Uttaranchal University, located in Dehradun, India by Director- Research and Innovation. The certificate file number is UU/DRI/EC/2025/004.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All participants were provided with information sheets and gave written consent prior to participating in this study. They were briefed about the study’s objectives, assured of privacy, and consented to the use of their anonymized information for disseminated materials arising from the study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article is available in the at figshare.com reference number 10.6084/m9.figshare.30739439.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to extend our gratitude to the volunteer participants from security service organizations, as well as to the personnel who shared their time and expertise for the study.