RESEARCH ARTICLE

Visual Social Media Use Moderates the Relationship between Initial Problematic Internet Use and Later Narcissism

Phil Reed1, Nazli I. Bircek1, Lisa A. Osborne2, Caterina Viganò3, Roberto Truzoli3, *

Article Information

Identifiers and Pagination:

Year: 2018Volume: 11

First Page: 163

Last Page: 170

Publisher ID: TOPSYJ-11-163

DOI: 10.2174/1874350101811010163

Article History:

Received Date: 21/6/2018Revision Received Date: 27/8/2018

Acceptance Date: 14/9/2018

Electronic publication date: 18/10/2018

Collection year: 2018

open-access license: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Public License (CC-BY 4.0), a copy of which is available at: (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode). This license permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background:

Little is known about the temporal directionality of relationships between problematic internet use and personality disorders such as narcissism.

Objective:

Although these two constructs are related at a single time, no existent study has determined whether initial problematic internet use is more strongly associated with subsequent narcissism, or vice versa. So, the aim of the research is to verify if problematic internet use predicts the narcissism or vice versa.

Methods:

Seventy-four university student participants were studied over a four-month period, and completed the Narcissism Personality Inventory, and Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire, at baseline and follow-up.

Results:

The results demonstrated a relationship between problematic internet use and narcissism at baseline. Time-lagged correlations demonstrated that problematic internet use at baseline was positively related to narcissism four-months later, but not vice versa for social media users whose use was primarily visual. This relationship did not hold for social media users whose use was primarily verbal.

Conclusion:

These results suggest that problematic internet use may serve to discharge narcissistic personality traits for those who use social media in a visual way, but not for those who do not engage in that form of internet use.

1. INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that between 6-18% of the younger population show some degree of digital-dependency or Problematic Internet Use (PIU) [1, 2]. PIU is manifest in terms of multiple negative impacts on the individual’s life [3], including the development of tolerance [4], and withdrawal effects when disconnected from the internet [5, 6]. Socially, there are negative impacts on friendship and increased loneliness [7]. Heavy internet use interferes with quantity and quality of sleep [8] and with healthy-eating and exercise [9]. Psychologically, there are increased levels of depression and anxiety [5, 10], as well as deleterious impacts on attention span [11], memory [12], and impulse control [13]. PIU is also associated with increased levels of illness [14] and immune function problems [15].

PIU is also associated with a range of clinical problems and personality traits [16, 17], including narcissism [18] [19]. In extreme forms, narcissism can be a clinical problem reflecting feelings of self-importance, unlimited success, uniqueness, as well as a lack of empathy, envy, and arrogance [20], but it also exists in subclinical forms in the general population. It has been suggested that social media can allow narcissistic individuals to express these traits, and to receive gratification of their needs [18, 21].

Moreover, self-promotion via social media may fuel narcissism, and engagement in visual forms of social media, such as self-portrait photographs featuring the user may be particularly important in this regard [22]. Indeed, there are studies that show a relationship between narcissism and the use of such self-portraits [21, 23]. This finding implies that the use of some forms of social media, particularly those which rely heavily on the use of visual content ( e.g. , Facebook, Instagram [24]), may be particularly important in moderating any relationship between PIU and narcissism. In contrast, it may be that social media usage that is primarily textual (Twitter, Snapchat) may not moderate this relationship to the same extent.

However, there have been no longitudinal studies of the relationship between PIU and narcissism. Although there is clear evidence of a relationship between the two constructs, it is not known whether those with higher levels of narcissism are likely, subsequently, to have higher levels of PIU; or whether those with higher levels of PIU are likely, subsequently, to have higher levels of narcissism. Consequently, the first aim of the current study was to study the relationship between these measures over a four-month period, and establish whether initial PIU is a stronger predictor of later narcissism than initial narcissism is a predictor of later PIU or vice versa.

The second aim of the current study is to explore whether the type of social media usage acts to moderate between PIU and narcissism, and vice versa, over time.

To these ends, the level of self-reported PIU and narcissism in a group of participants were measured at baseline, and again after four months. The participants were also asked about their usage of the internet and social media, and the predominant forms of usage were determined. These data were then analysed to establish the time-lagged relationship between initial PIU and subsequent narcissism, and between initial narcissism and subsequent PIU. In addition, the current study explored whether the use of visual or verbal forms of social media moderated any emerging relationships.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Participants

Seventy-four participants (19 male and 55 female) were recruited initially, and all completed the study. All participants were students from a Psychology Department of a University in the UK, and all were volunteers – none received any form of compensation. The participants mean age at baseline was 23.09 (SD + 3.42; range = 18 – 34) years. Younger participants were thought appropriate to target as they are most commonly affected by PIU [3, 25]. Power calculations suggested that for an estimated small effect size f’ = .15, with 80% power, and a significance criterion of p < .05, a sample size of 67 would be necessary for a regression analysis with one predictor and one moderator variable.

2.1.1. Design of study

Because of lack of longitudinal studies in the literature, we applied a longitudinal observational study.

2.1.2. Data analysis

For estimating the relationship between predictor variables and a dependent variable, we applied a multiple regression. Because our study is longitudinal, we used a time-lagged correlation. This correlation extends linear Pearson correlation by determining the best correlations among variables shifted in time.

2.2. Materials

2.2.1. Narcissism Personality Inventory

(NPI-40 [26]) is 40-item inventory measuring the extent of a narcissistic personality. The total scale gives a score from 0 to 40. The baseline internal reliability (Cronbach α) was .792, and α at follow-up was .814.

2.2.2. Problematic Internet Use Questionnaire

(PIUQ [27]) is an 18-item questionnaire designed to measure the degree to which internet use disrupts an individual’s life. The total scale gives a score between 0 and 56. There are three sub-scales that measure obsession, neglect, and control disorder. The baseline internal reliability (Cronbach α) was .865, and α at follow-up was .901.

2.2.3. Demographics and Internet Use

Participants were asked about their age and gender. They were also asked to estimate their average hours of internet usage per day for personal reasons (excluding work), over the last few weeks. Personal use has been shown to correlate more strongly with PIU than a combined measure of personal and work use [14]. Participants also were asked to list the specific websites, apps, or platforms that they used, in order of frequency of usage.

2.3. Procedure

Participants were sent an online survey via email, which they completed online with the data saving automatically to an EXCEL file. Four months after they completed the initial baseline survey, they were sent the survey again via e-mail, and they completed and returned it in the same way. All surveys were completed and returned within one week of their being sent to the participant. Participants compiled NPI-40 and PIUQ, and provided demographic and Internet use data.

3. RESULTS

The sample-mean personal use was 4.92 (+ 1.60; range = 1 – 7) days per week (work usage was excluded as it does not predict PIU as strongly [14]). The sample-mean personal usage per day was 2.92 (+ 1.83; Range = 1 – 8) hours.

In terms of the reasons for internet usage: 74 participants (98%) cited social networking, 70 (93%) research, 64 (85%) shopping/banking, 61 (81%) news and information, 61 (81%) entertainment, 46 (61%) content sharing, 17 (23%) gaming, 12 (16%) sexual content, 8 (11%) dating, 7 (9%) traditional blogging, 4 (5%) chat rooms, and 3 (4%) gambling.

Of the social media usage, 44 (59%) participants cited Facebook in the top three platforms and websites that they used, 17 (23%) participants mentioned Instagram, 10 (13%) Twitter, and 10 (13%) Snapchat. Broadly classifying these usages as visual (Facebook and Instagram) revealed that 50 (67%) used visual forms of social media, and 16 (21%) used social media in a primarily verbal way.

Table 1 shows the baseline and follow-up means for narcissism (NPI), problematic internet use (PIUQ), and hours a day personal use for the sample, as well as the Pearson correlations between the variables.

| Mean (SD) | Baseline PIUQ |

Baseline Use |

Follow NPI |

Follow PIUQ |

Follow Use |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline NPI | 12.89 (5.81) | .212 | -.220 | .828*** | .144 | -.202 |

| Baseline PIUQ | 23.21(10.86) | – | .261* | .089 | .812*** | .305*** |

| Baseline Use | 3.16 (1.91) | – | – | -.204 | .183 | .624*** |

| Follow NPI | 12.33 (6.05) | – | – | – | .004 | -.233* |

| Follow PIUQ | 22.45(11.49) | – | – | – | – | .348** |

| Follow Use | 2.91 (1.94) | – | – | – | – | – |

The sample was split into groups who either did use (50; 68%) or did not use (24; 32%) visual forms of social media (Facebook, Instagram); and those who either did use (16; 22%) or did not use (58; 78%) verbal forms of social media (Twitter, Snapchat, Tumblr). Table 2 shows means (standard deviations) for the narcissism (NPI), problematic internet use (PIUQ), and personal use (hours/day) for baseline and follow-up for the sample split into those who use and do not use visual and verbal forms of social media. Inspection of these data show few significant differences between the groups in terms of these scores at either baseline or follow-up.

| Visual | Verbal | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| User | Non-user | t | User | Non-user | t | |

| Baseline NPI | 13.07 (5.56) | 12.67 (5.97) | .45 | 13.25 (5.80) | 11.84 (5.84) | .91 |

| Baseline PIUQ | 21.19 (8.04) | 24.29 (12.06) | 1.18 | 21.73 (10.45) | 27.47 (11.15) | 2.03* |

| Baseline Use | 2.92 (1.83) | 3.29 (1.96) | .79 | 2.96 (1.74) | 3.76 (2.28) | 1.54 |

| Follow NPI | 12.31 (5.96) | 12.34 (6.17) | .02 | 12.55 (5.75) | 11.67 (7.05) | .53 |

| Follow PIUQ | 20.93 (11.67) | 23.27 (11.43) | .83 | 21.13 (11.31) | 26.26 (11.45) | 1.71 |

| Follow Use | 2.19 (1.17) | 3.29 (2.17) | 2.39** | 2.64 (1.83) | 3.68 (2.08) | 2.07* |

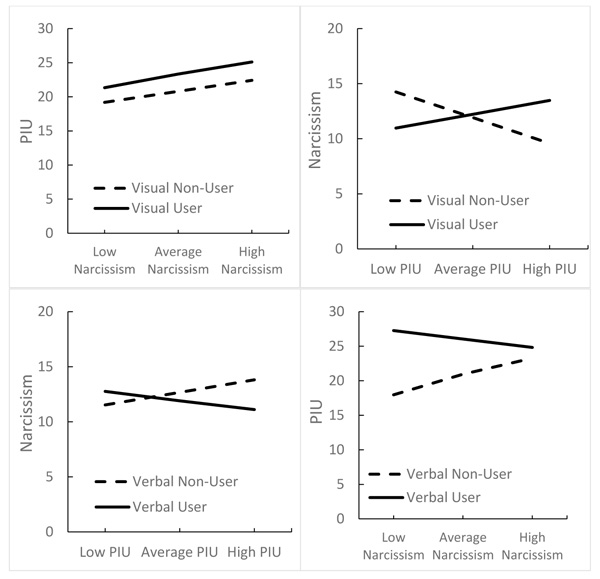

To test the hypothesis that narcissism at follow-up is a function of baseline problematic internet use, and whether being a visual user moderates this relationship, a multiple regression was conducted. In the first step, baseline PIU and visual use were entered. These variables did not account for a significant amount of variance in follow-up narcissism, R2 = .251, F(2,70) = 2.11, p = .106. To avoid potentially problematic high multicollinearity with the interaction term, the variables were centred, and an interaction term between baseline PIU and visual use was created [28]. The interaction term between PIU and visual use was added to the regression model, which accounted for a significant proportion of the variance in narcissism, ΔR2 = .055, ΔF(1,70) = 5.99, p < .01, b = .225, t(70) = 2.45, p < .01. Examination of the interaction plot (top left panel Fig. 1) showed that as baseline problematic internet use increased, follow-up narcissism increased for visual users, but reduced for non-visual users.

To test the hypothesis that follow-up PIU is a function of baseline narcissism, and whether being a visual user moderates this relationship, a multiple regression was conducted. In the first step, baseline NPI and visual use did not account for a significant amount of variance in follow-up PIU, R2 = .179, F(2,70) = .71, p > .50. When the interaction term between baseline NPI and visual use [28] was added to the model, it did not account for a significant proportion of the variance in follow-up PIU, ΔR2 = .001, ΔF < 1, b = .028, t(70) < 1. Examination of the interaction plot (bottom left Fig. 1) shows that, numerically, as NPI increased, PIU increased.

To test the hypothesis that follow-up narcissism is a function of baseline PIU, and whether being a verbal user moderates this relationship, a multiple regression was conducted, with baseline PIU and verbal use in the first step, which did not account for a significant amount of variance in follow-up narcissism, R2 = .183, F < 1. When the interaction term between baseline PIU and verbal use [28] was added, it did not account for a significant proportion of the variance in follow-up narcissism, ΔR2 = .019, ΔF < 1, b = -.182, t < 1. Examination of the interaction plot (top right Fig. 1) showed that as problematic internet use increased, narcissism increased for non-verbal users, but not for non-users.

To test the hypothesis that follow-up PIU is a function of baseline NPI, and whether being a verbal user moderates this relationship, a multiple regression was conducted. Baseline NPI and verbal accounted for a significant amount of variance in PIU, R2 = .302, F(2,70) = 2.62, p < .05. The interaction term between baseline NPI and verbal use [28], did not account for a significant proportion of the variance in narcissism, ΔR2 = .025, ΔF(1,71) = 1.37, p = .247, b = -.724, t(70) = 1.17, p = .247. Examination of the interaction plot (bottom right Fig. 1) showed that as NPI increased, PIU decreased for verbal users, but increased for nonverbal users.

4. DISCUSSION

The current study noted that initial levels of Problematic Internet Use (PIU) predicted subsequent levels of Narcissism (NPI), but only for those who used primarily visual forms of social media. This relationship was not seen for those who reported that they used social media in primarily verbal ways. There was also a smaller relationship between levels of narcissism at baseline and subsequent levels of problematic internet use, but these were not as strong as the above temporal relationship.

The current study also noted that this relationship was moderated by the nature of social media usage. Social media usage was virtually universal in the current sample, but the form in which they primarily used social media differed. The majority of the sample used primarily visual forms of social media – those involving sending images. Those who used the social media in this manner were more likely to show the relationship between initial levels of PIU and subsequent levels of narcissism, noted above, than those who tended to employ social media in verbal forms.

The reasons for the association between initial levels of PIU and subsequent levels of narcissism will need to be explored further. However, one suggestion that has some degree of face validity, in relation to previous evidence, is that PIU may impact and reinforce the self-esteem of individuals with high levels of narcissistic traits [19]. The use of visual forms of social media, such as Facebook and Instragram, may help to emphasize and facilitate the perception of such individuals that they are the focus of attention, and to satisfy their needs to be admired [18]. Contacting the world through a visual modality in a virtual arena, without the possibility of immediate ‘direct’ social censure, may offer the opportunity to discharge (or inflict) some aspects of narcissistic personality [29]. This provides the individual with opportunities to present themselves in a grandiose manner, and to realize their fantasies of omnipotence [18, 29]. Of course, there are a number of limitations to the current study.

Internet use and social media usage was assessed through self-report, and not objective means, and the classification of social media usage into primarily visual or verbal on the basis of the type of social media platform preferred may not be as fine-grained as it could be. However, that the effect emerged, suggests that these results warrant further investigation. It may also be useful to explore the particular components of narcissism ( e.g. , vanity, exploitativeness, etc.) that are most impacted by internet usage. This was not attempted in the current study due to the sample size. The analysis of the components of narcissism could be the goal of future research.

Another limitation is about the external validity of the findings that can be problematic as we used a convenience sample of students. In future research, a random sampling from the general population could be used.

A third limitation concerns the fact that the four months time lag may bring in some confounding factors. However, in a longitudinal study, the time interval must be long enough to detect the change in status. Probably four months is enough time to detect changes in time and not so large as to greatly increase the risk of confounding events. Also, it is true that the regression models look at the relationship between key variables, but one can evaluate whether variables predicts another.

Furthermore, it should be noted that our study had a participation rate equal to 100% of the initial sample, overcoming one of the general risks of longitudinal studies.

On the other hand, the results of the study are in accordance with previous findings on Internet use and narcissism [21].

CONCLUSION

This is the first study to examine the longitudinal relationship between levels of problematic internet use and narcissism, and suggests that, although there may be a bidirectional relationship over time, PIU appears to drive levels of narcissism. This has been suggested in previous cross-sectional studies, an effect also noted in the current study, but which has not been demonstrated over time [18, 21].

Furthermore, the relationship between initial levels of PIU and subsequent levels of narcissism moderated by the mainly visual use of social media has been predicted, but not demonstrated, previously [21, 23].

The current study demonstrated that problematic internet use does predict subsequent levels of narcissism and that this was moderated by visual forms of social media engagement. So our study confirms the hypothesis that problematic internet use may serve to release narcissistic personality traits for those who use social media in a visual way only.

These findings suggest further reasons to be concerned over the psychological impacts of digital technology, especially for younger users.

The results of the study can be used for preventive actions. As it is known that NPI scores increased as the self-esteem decreased, educational interventions for younger users can be planned by improving self-esteem levels, especially related to self-image with guided exercises, and increasing awareness of the risks of sharing self-images on social networks, posted only with the aim of appearing. The intervention could be useful to prevent a pathological narcissistic regulation, maybe more when the predominant features are the organization of the sense of self around the adolescent's beauty, coupled with an ongoing need for admiration from others.

From a clinical point of view, the psychologist should evaluate, in addition to the levels of Internet addiction and the use of social networks in a visual way, also the levels of narcissism, and the subjective historical relation between problematic use of the Internet and narcissism. If this is the case, the psychologist may apply psychotherapy to deal with Internet addiction and dysfunctional personality trait.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are base of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The manuscript has not individuals’ data, such as personal detail or audio-video material. Standard informed consent was obtained for participation in research.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Author Contributions: Conceptualization PR, LAO, RT, CV; methodology PR; LAO, NB, RT; collected data NB; analyzed data PR; writing-first draft PR, NB, LAO, CV, RT; writing-editing PR, LAO, RT; supervision RT.