All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Male Partners’ Portion of Date Among Heterosexual College Students: Changes from 1999 to 2014 in Korea

Abstract

Background:

Traditionally, men are perceived as the initiators of dating activities, with women as submissive followers. In this view, paying for a date is the responsibility of the man.

Methods:

This study examined how much money Korean heterosexual college men have paid for dates during the past decade.

Results:

Many women have become initiators of the dating process as society has become more egalitarian, but many studies have reported that men still pay for the first few dates.

Conclusion:

Men have paid about 72% of all the expenses for a date in 1999 but the ratio dropped to about 63% in 2014.

1. INTRODUCTION

Dating typically involves a rather formal pattern in which participants know one another, or want to get to know each other, with a perceived possibility of a future relationship [1]. Dating usually involves a set of normatively guided social relationships and activities, which requires some expenses for the participants [2]. Traditionally, men play a more active role in dating activities, including asking a woman out, planning the date, paying for the date, and taking her home. In comparison, women have been expected to take on the submissive role during dating, including being picked up and responding or supporting the man’s initiation and overtures [1, 3-6].

Shifting into an industrialized society, the gender roles have become more androgynous and the process of dating has shifted into less traditional ways. The emergence of modern dating, in which partners equally share all burdens and responsibilities, has been due to numerous factors including the surge of the women’s equality movement. As women have increased their access to earned income, there has been a rising ideological and behavioral commitment to egalitarian relationships [3, 6, 7]. Women have even reported an increased desire for more equal relationships [4].

However, despite the shifting culture in dating, many men and women still adhere to the traditional script for the first date [1]. In order to determine whether the current dating norms and practices of young people have progressed toward an egalitarian feminist ideal, Eaton and Rose [3] reviewed 94 articles from the late 1970s to 2010 on the topic of heterosexual dating amongst young adults. These articles were published in the journal Sex Roles. They concluded that despite these destabilizing shifts, traditional gender ideologies remain remarkably resilient, as courtship conventions symbolizing men’s dominant, breadwinning status stubbornly persist [3].

Additionally, the initial dating practices of college students consistently appear to be primarily traditionalistic. It was reported that 92% of college men and 78% of college women believed the male should pay the bill on a date [8]. According to a study of college students, first-date script research has found much consistency with traditional gender roles [9]. In a separate survey polled from teenagers to 60 year olds, 84% of the males and 58% of the females reported that the male should pay for the first date [10]. Despite that the male-oriented script has been shifting to a more egalitarian script, the traditional dating script perseveres in the first few dates [6, 11].

In an in-depth interview with college students by Jaramillo-Sierra and Allen [11], nearly all the young men (29 out of 34) stated men should pay for all the expenses of the first date or the initial period of dating. Initial payment rules generally included paying for meals, movie tickets, and gas. For the most part, men said that they were responsible for driving young women from their home to the date and driving them back home after the date was finished. There were three predominant explanations young men used to justify why they should always pay for the first date or the initial dating period: (a) giving a good impression, (b) showing how much they care, and (c) doing “the socially acceptable thing”. Another study by Lamont [2] reported similar reasons for heterosexual males.

South Korea has been slower to join the shifting trend towards an egalitarian society. Gender equality has only recently become emphasized since the late 1990s. The Department of Gender Equality was founded in 2000 and, around the same time, gender equality was introduced into basic sexuality education programs in primary and secondary schools across the nation [12]. The purpose of this study was to explore if there has been any changing trends from the traditional scripts of the dating culture in Korea from 1999 to 2014, using reported payments on dates based on gender. Although many studies of the evolutionary psychology field have indicated that men tend to invest more resources in dating than women [13-15], this was an exploratory study examining the changing trends.

2. METHODS

2.1. Participants

Participants were 6,863 full-time college students who were enrolled in either Introduction to Psychology or Psychology of Human Sexuality from the spring semester of 1999 to the fall semester of 2014 at a large national university located in the southwestern Korea. Of the 6,863 respondents, 3,943 (57.45%) were female and 2,920 (42.55%) were male. All participants identified themselves as heterosexual, single and never married, between 18 to 26 years of age, and had prior heterosexual dating experience in the past 3 months.

2.2. Data Collection

An average of 500 students enrolled in the Introduction to Psychology course, while an average of 150 students enrolled in the Psychology of Human Sexuality course every semester from 1999 to 2014 at the aforementioned university located in Gwangju, Korea. At the start of the semester, when students were into their classrooms, they were provided a survey of less than a half page to answer responses concerning gender, the amount spent in Korean Won by both parties on the most recent date, the amount spent personally (in Korean Won) on the same date, and four questions of inclusion criteria for participation in this study. The inclusion criteria were: 1) age between 18 and 26 years, 2) never married, 3) heterosexual, and 4) prior dating experience during the past 3 months. Participants remained anonymous and surveys were collected at the end of the class in a collection box. Individuals who met the inclusion criteria and participated in the survey ranged from 279 to 611 each year. They were all full-time students, but there were no data whether they were employed or not for the 3 past months.

3. RESULTS

The dependent measure was the percentage of total expenditures that Korean males paid in the most recent date. In male participants, the measure was derived by the percentage they had spent, themselves, on the date. However, in female participants, the measure was derived by the percentage that her male partner had spent in the date (compared to the total expenditures). Table 1 depicts the average percentage that Korean males reported they spent in a single date per year, the average percentage that Korean females reported their partners spent in a single date per year, the average that a Korean male spent in a single date based on the sample per year, and the average in total expenditures spent. A decreasing trend was evident in the average a Korean male spent on a single date across all three parameters (male, female, and averaged total) from approximately 72% in 1999 to 63% in 2014 (Table 1). Data was plotted onto a scatter plot using linear regression to find a regression line.

| Year | Sample | Total Expensesb |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Total | |||||

| n | Percentagea | n | Percentagea | N | Percentagea | ||

| 1999 | 166 | 73.01 (26.01) | 293 | 71.65 (27.49) | 459 | 72.14 (26.94) | 23,388 |

| 2000 | 170 | 68.74 (28.23) | 297 | 70.32 (24.61) | 467 | 69.75 (25.96) | 25,319 |

| 2001 | 252 | 71.11 (24.43) | 305 | 70.60 (22.79) | 557 | 70.83 (23.53) | 30,494 |

| 2002 | 177 | 69.32 (25.44) | 200 | 72.16 (25.39) | 377 | 70.82 (25.42) | 37,135 |

| 2003 | 128 | 67.93 (26.83) | 181 | 71.20 (25.36) | 309 | 69.85 (25.98) | 37,226 |

| 2004 | 252 | 69.78 (23.02) | 359 | 70.23 (21.89) | 611 | 70.05 (22.35) | 36,717 |

| 2005 | 166 | 69.48 (24.36) | 205 | 68.08 (26.10) | 371 | 68.70 (25.31) | 36,349 |

| 2006 | 254 | 69.07 (23.04) | 326 | 68.75 (23.63) | 580 | 68.89 (23.35) | 37,227 |

| 2007 | 240 | 68.07 (22.19) | 253 | 66.30 (22.47) | 493 | 67.16 (22.33) | 44,043 |

| 2008 | 216 | 66.78 (24.03) | 316 | 69.42 (21.14) | 532 | 67.75 (22.35) | 47,730 |

| 2009 | 146 | 69.51 (22.69) | 189 | 69.76 (18.88) | 335 | 69.65 (20.60) | 50,010 |

| 2010 | 135 | 68.48 (20.70) | 148 | 66.00 (24.45) | 285 | 67.18 (22.75) | 50,323 |

| 2011 | 174 | 68.47 (23.05) | 221 | 65.57 (20.99) | 395 | 66.85 (21.94) | 51,400 |

| 2012 | 131 | 65.22 (18.01) | 148 | 66.33 (20.55) | 279 | 65.81 (19.37) | 51,513 |

| 2013 | 172 | 63.17 (20.96) | 322 | 64.60 (21.21) | 494 | 64.10 (21.11) | 51,740 |

| 2014 | 139 | 64.31 (23.50) | 178 | 62.31 (23.77) | 319 | 63.19 (23.63) | 52,200 |

| Total | 2,920 | 68.46 (23.72) | 3,943 | 68.47 (23.35) | 6,863 | 68.47 (23.50) | 40,456 |

b: The average in total expenditures spent (the unit of expense for the date was Korean Won; US$ 1.00 = Korean Won 1,100).

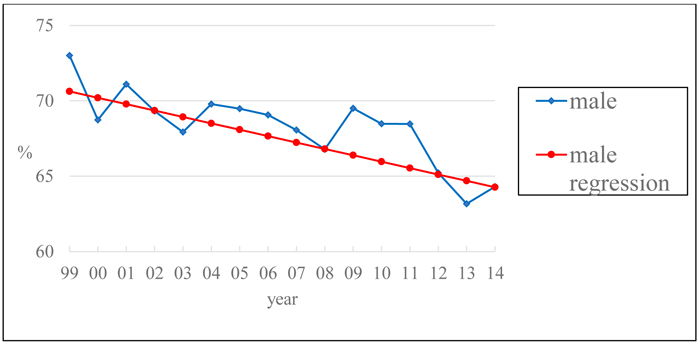

Note. X-axis: year from 1999 to 2014

Y-axis: % of total expenses paid by Korean males.

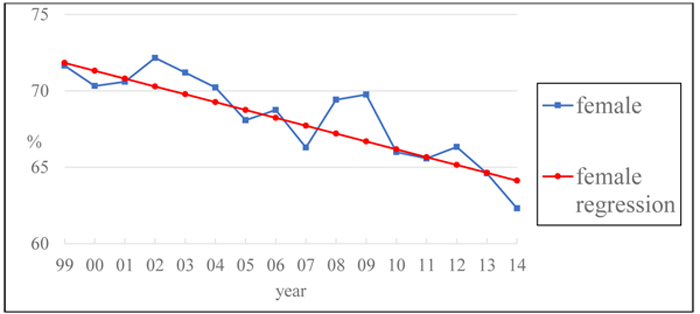

On the average reported by the Korean male participants (Fig. 1), the regression line fit the data well (F1,2918 = 18.20, p < .001). The regression equation was given by “Y (men’s % of paying for date) = 918.204 - .424 * Year.” Using the regression equation, predicting ratios reported 70.63% in 1999, 64.27% in 2014, 59.60% in 2025, 55.36% in 2035, and 51.12% in 2045. On the average reported by the Korean female participants (Fig. 2), the regression line fit the data well (F1,3941 = 40.51, p < .001). The regression equation was given by “Y (females’ partner’s % of paying for date) = 1099.318 - .514 * Year.” Using the regression equation, predicting ratios were reported as 71.83% in 1999, 64.12% in 2014, 58.47% in 2025, 53.33% in 2035, and 48.19% in 2045.

Note. X-axis: year from 1999 to 2014

Y-axis: % of total expenses paid by Korean males.

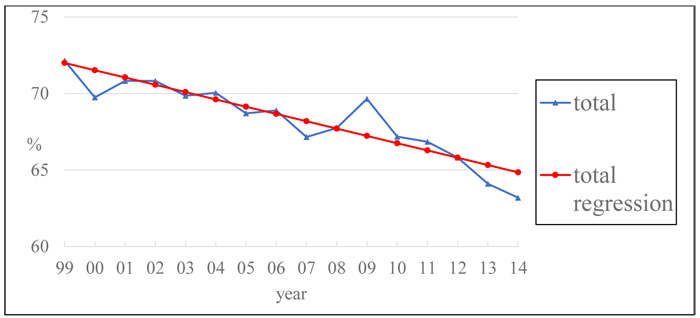

Based on the total sample of Korean males and females that participated in the survey per year (Fig. 3), the regression line on the average percentage that a Korean male spent in a single date fit the data well (F1,6861 = 57.97, p < .001). The regression equation was given by “Y (average men’s % of paying for date) = 1025.524 - .477 * Year.” Using the regression equation, predicting ratios reported 72.00% in 1999, 64.85% in 2014, 59.60% in 2025, 54.83% in 2035, and 50.06% in 2045.

Note. X-axis: year from 1999 to 2014

Y-axis: % of total expenses paid by Korean males.

4. DISCUSSION

The so-called sexual revolution took place in the 1960s in the United States, whereas South Korea’s sexual revolution did not come until the late-1990s [16, 17]. From the late-1990’s, gender equality has become more prominent in South Korea and has rapidly shifted the traditional male-oriented heterosexual relationships into egalitarian relationships. One reported notable shift was that women began to initiate dates with men [17]. However, women who initiate are still seen as a social violation of traditional dating norms and culturally assumed that women who do so had greater coital wishes than male date-initiator [18].

This study aimed just to give a general view on the dynamic of dating expenditure among the Korean heterosexual college students. The main findings show that, regardless of the timing in the date (i.e., first date or subsequent dates), the trend in which gender pays more in a date is leaning towards a more egalitarian setting. Considering that males appear to pay for the first few dates, heterosexual couples frequently alternated payment for the subsequent dates between the two of them [2-4]. Thus, the percentage that males paid for their dates may be closer to 50% if the data had specified and excluded first dates. Based on the data of the total sample, it took almost 20 years for a 10% decrease in the Korean males’ percentage of contribution in expenses on a date. Thus, we predict the percentage to reach 50%, where males and females pay equally, by 2045.

CONCLUSION

However, there are several limitations to the generalization of the findings. First, timing of the date was not included, and the purpose of the date was not asked either. Distinguishing between a first date and a committed relationship can differentiate which gender party paid more. Second, financial backgrounds of the partners to the college students were unknown. Based on whether their partners were working one might expect those who could afford more to pay more, although all of the respondents were full-time students. Future studies can include these parameters for stronger results. Nevertheless, the findings in this study show that the traditional dating scripts are changing during the past decade or so in Korea.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are base of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.