All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Modeling the Effect of Organizational Justice on Employee's Well-Being, Organizational Citizenship Behavior and Turnover Intentions through Employee Engagement

Abstract

Introduction:

The last two decades had witnessed an increased interest in employee engagement by the academician and the practitioner. The reason for such interest is employee engagement potential to influence the individual and organizational level consequences.

Methods:

Hence, the current study's objective was to identify the key antecedents and consequences of employee engagement and establish their inter-relationship. Apart from this, the study also validates the different scales to measure different antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. The data were collected from 656 employees working in the FMCD industry in India to achieve this objective.

Results:

Results of the structural equation modeling analysis show that perceptions of organizational justice positively impact employee engagement. Further, employee engagement positively impacts satisfaction with life, positive affect, and organizational citizenship behavior.

Conclusion:

However, employee engagement showed a negative relationship with negative affect and employee turnover intentions. In the end, the practical and theoretical implications of the study were discussed.

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, studying employee engagement has gained more attention from researchers and academicians than before. Employee engagement is characterized as cognitive, psychic, and behavioral effort for effective organizational performance by the employee [1]. Studies have shown that engaged employees are more likely to be effective [2, 3], staying with their same employer [2, 4], and connecting favorably towards consumers [5]. Initially, Kahn described employee engagement as the “harnessing of organizational members' selves to their work roles”. In engagement, Kahn also mentioned that “people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively, and emotionally during role performances” [6]. This conceptual model portrays engagement as an adaptable term with known connections to performance, yet, one-fourth of a century ago remains a very vague and loosely described term considering the pervasive interest in engagement [7].

Kahn initially suggests that there is a substantial correlation between engagement and other cognitive concepts, such as job contentment, loyalty, and inspiration [6]. Macey and Schneider [8] found that employee engagement is a chaotic construct expressed as an emotional condition in different forms (like connection or commitment, involvement), a construct of success (like connection or commitment, involvement), and/or different ordering (i.e., a trait). Maslach [9] creates a distinction between “job engagement” and “employee engagement”; however, these words are switchable, and it is easier to understand in utilizing than to describe them as most psychological terms [10]. Truss [11] beautifully combines the distinction between the two saying that employee engagement “is a way taken by companies to handle their workers”.... while workplace engagement is ...”A behavioral environment faced in the success of their jobs by employees;' performing engagement' rather than to be engaged”.

Both professionals and researchers also advocate recognizing the nature of workplace engagement by assessing engagement via an employee opinion as the most effective strategy to evaluate employee engagement [12]. “Nevertheless, as has been mentioned, the amount of staff participating remains low and” the gap between the assumed value of engagement and the degree of engagement in organizations today [13]. It is of interest that assessment alone cannot clarify why workers are disengaged, how engagement can be produced, and how other beneficial results such as success and well-being can be positively influenced [14], providing the professional no insight into how workers can be engaged. It is essential to identify the factor that affects an employee's engagement, which has various organizational consequences.

Therefore, the current study objective is to identify the key antecedents and consequences of employee engagement and establish their inter-relationship.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK AND ANTECEDENTS OF EMPLOYEE ENGAGEMENT

The Social Exchange Theory (SET) [15] offers an essential theoretical framework for understanding whether workers want to be more or less engaged with their job in their company. It also serves as a well-established analytical context to know how individual's understanding of organizational justice can impact their engagement to their job and organization. This theory suggests that a sequence of contacts between parties creates obligations “A central principle of SET is that, as long as the parties concerned adhere with certain laws of trade, partnerships grow over time into trusting, loyal and reciprocal obligations” [15].

“The literature on organizational justice is vast and has been inspired by the belief that employees who think they are treated fairly will be disposed of favorably by the employer and engage in prosocial acts on behalf of a company [16]. Organizational equity, which illustrates worker’s observed dignity in the workplace, regulates their social contact relationships [17]. Extensive study has shown organizational fairness is directly related to the standard of social interaction between people and their organizations within the SET system [18] and contribute to employee engagement [19]. When employees in their organization have clear perceptions of honesty, they are often more likely to be obligated to be equal in performing their roles by providing more significant degrees of engagement and providing more of themselves [15]. On the opposite, wrong perceptions expectations are likely to lead workers to retreat from their job positions and disengage themselves [19]. Equality and fairness are one of the job conditions, too. The engagement model of Maslach et al. [20] suggesting that favorable views of fairness will boost engagement [20]. Hence, in the current study it is expected that when an employee perceives fairness at their workplace in the form of distribution, procedure, and interaction, then it will lead to a positive organizational consequence, that is, employee engagement. Further, employee engagement is expected to have different organizational consequences (positive and negative consequences).

Work engagement is also investigated in the form of the Job Demands-Resource (JD-R) theory, as employee disengagement has been correlated with a shortage of resources [21]. The physical, cognitive, social, or operational aspects of the job that are functional in achieving job goals are also the work tools [22]. In addition, procedural justice, distribution of resources, and interactional fairness perspectives can be seen as instruments that can be instrumental in raising employee engagement because of their realistic role in achieving agreement.

Honesty was recognized as a significant indicator of the affective conditions and attitudes of workers by several scholars. One of the six work-life causes contributing to Work Engagement (WE) result in exhaustion literature is equity and justice [20]. Burnout will accentuate a sense of justice, whereas engagement can be strengthened by a positive view of justice [20]. A variety of literature [23-26] indicate that workers conclude that corporate policies and management steps are unfair or unjust, they encounter emotions of indignation, outrage, and resentment, and can also participate in acts of revenge or aggression [25, 27, 28]. On the opposite, workers are more likely to be equal in their positions because they have a high sense of fairness in their company through offering more of themselves by higher degrees of engagement [2] and reciprocating through displaying attitudes of corporate citizenship [29-32]. Past research [24] has demonstrated that how disengagement of workers can be explained by corporate inequality. Therefore, the following hypothesis has been proposed.

2.1. H1: Perceptions of Organizational Justice has a Positive Effect on Employee Engagement

2.1.1. Consequences of Employees Engagement

Employee engagement is a constructive influence that motivates and ties workers mentally, intellectually or physically, toward the company [6, 33]. Ibrahim and Falasi [34] identify the importance of engagement in the public sector of the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The authors suggested that management should discuss employees' things to boost employee morale, job satisfaction and lead the business to meet targets. Consequently, employee engagement is a crucial topic for top executives [35], as the staff is the core commodity of each organization [36]. Many scholars reported a high level of correlation between engagement and net sales generation [37, 38].

The research by Schaufeli et al. [39] highlighted the negative relation between engagement and burnout. Burnout, a three-component well-being model, is one subdomain [40] highlighted in early work by Schaufeli et al. [39] and concluded that burnout would affect the performance and growth of employees. Different researchers [39, 41] proposed a basic analysis of mental fatigue, depersonalization, and personal success as individually oriented indices of well-being have been proposed.

2.2. H2: Employee Engagement has a Positive Effect on Employee Well-Being

● H2a: Employee engagement has a positive effect on satisfaction with life

● H2b: Employee engagement has a positive effect on positive affect

● H2c: Employee engagement has a negative effect on negative affect

Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB) is discretionary conduct that benefits the organization that the employer is not formally requested or compensated by the employer [42]. OCB includes workers moving willingly above their work criteria even though they have not demanded those acts and do not officially award those acts. OCB can be defined in the form of the Social Exchange Theory (SET). The social exchange was discovered to be a motivator for OCB by employees [43]. SET claims that duties or liabilities are generated by a sequence of relations among parties in a mutual state of interdependence [2]. In other words, based on the compensation now received by the company or the expected benefits, workers correspond with OCB. It was referred like OCB-O by Williams and Anderson [44]. Workers could also reciprocate OCB to their interdependent colleagues because of the other employee’s benefits, either earned or expected. It was referred to as OCB-I by Williams and Anderson [44]. However, regardless of multiple personality characteristics, individuals differ in their ability to exhibit OCB. For example, personality traits such as conscientiousness and altruism (an attribute of compatibility that reflects the propensity to be selfless) have been recognized as an OCB component [43, 45, 46]. While recent studies have documented a relationship between employee engagement and OCB, this potential relationship in the FMCD sector is little understood, especially in emerging economies such as India. It is also necessary to further affirm the ties between employee engagement and OCB, considering the constantly evolving job relationships and workplace management processes in many foreign business environments.

2.3. H3: Employee Engagement has a Positive Effect on Organizational Citizenship Behavior

Bothma and Roodt [47] define turnover intent, i.e., “a mental dominant decision between a personal's approach with reference to work to pursue or quit the work”. The final cognitive step in the decision-making phase of voluntary turnover is the decision to stay/ leave an organization [48]. According to Harhara et al. [49], the purpose of turnover is “a measure to recognize turnover before staff either quit or quit organizations.” Since approaching turnover at the root of its cause would be advisable, the present study aims to concentrate on “turnover intention” rather than on real turnover. It is also possible to regard personality as the immediate determinant of motives [50] and real behavior [51]. To predict turnover intentions among IT workers, numerous human, organizational and environmental features are found [49, 52-55]. A meta-analysis of 33 studies by Joseph et al. [56] described 43 antecedents of IT practitioner’s attrition intentions. Using Meta-analysis SEM, constructs such as job satisfaction; recognition of job alternatives; personal, task-related, and organizational variables were defined as antecedents among IT employees of turnover intention. Empirical research suggests that the purpose of turnover is linked to actual turnover [49, 57-59] and is censorious to managers [60]. Wasmuth and Davis [61] assume that turnover will often arise from frustration with aspects relevant to the current job instead of attracting an upcoming employment opportunity. There is also proof to suggest that work behaviors such as happiness, organizational commitment, Organizational Citizenship Behavior (OCB), respect for leadership, etc., are factors that intervene with turnover [62, 63]. These results point to a possible association between the purpose of turnover and the comparatively recent “employee engagement” definition. It is said that employee engagement contains several components of both dedication and OCB and is superior to both [64]. Malik and Khalid [65] identified engagement to be linked to the decision to leave and the psychological contract. There is a clear relationship between engagement and employee turnover [66]. Engagement and embeddedness were defined by Halbesleben and Wheeler [67] as unique structures predicting the intention to exit. Bonilla [68], Caesens et al. [69], and Kasekende [70] studies have shown that engaged workers are less prone to turnover.

2.4. H4: Employee Engagement has a Negative Effect on Employee's Turnover Intentions

2.4.1. Employee Engagement as Mediator

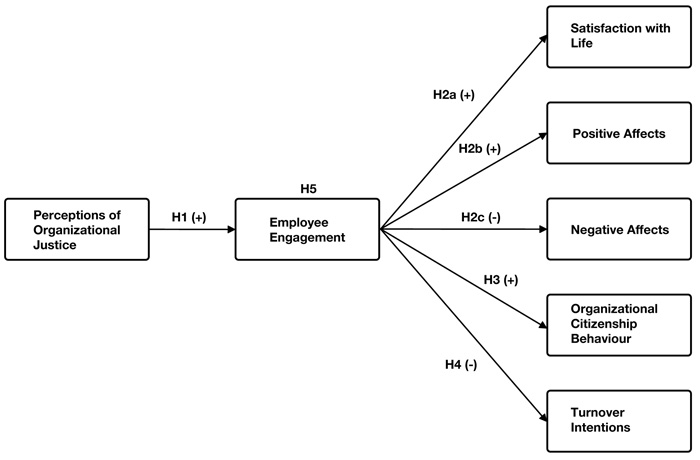

Based on the above discussion, in the current study, researchers have taken employee engagement as a mediator and perceptions of organizational justice as antecedent and employee's well-being, organizational citizenship behavior, and employee's turnover intentions as consequences of employee engagement (Fig. 1). Hence, the following hypothesis is devised based on H1-H4.

2.5. H5: Employee Engagement Mediates the Relationship between Perceptions of Organizational Justice, Employee's Well-being, Organizational Citizenship Behavior, and Employee's Turnover Intentions

● H5a: Employee engagement mediates the relationship between perceptions of organizational justice and satisfaction with life.

● H5b: Employee engagement mediates the relationship between perceptions of organizational justice and positive affect.

● H5c: Employee engagement mediates the relationship between perceptions of organizational justice and negative affect.

● H5d: Employee engagement mediates the relationship between perceptions of organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior.

● H5e: Employee engagement mediates the relationship between perceptions of organizational justice and employee's turnover intentions.

3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.1. Materials

3.1.1. Employee Engagement

To measure employee engagement, the researchers used the scale proposed by JRA [71]. The scale consists of three sub-scales (“emotional component, behavioral component, and cognitive component”). There are two statements in each sub-scale. The statements were asked to the respondents on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). The sample items consist of “Overall, I'm satisfied with my job, I feel inspired to go the extra mile to help this organization succeed, I take an active interest in what happens in this organization”. The Cronbach's alpha value of the emotional component was 0.837, for the behavioral component was 0.861, and for the cognitive component, the Cronbach's alpha value was 0.758.

3.1.2. Turnover Intentions

To measure the employee turnover intentions, the researchers used the scale proposed by Yücel [72]. The scale consists of three items. The statements were asked to the respondents on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). The sample items consist of “I intent to make a genuine effort to find another job over the next few months, I intend to leave the organization”. The Cronbach's alpha value of the employee turnover intentions scale was 0.937.

3.1.3. Perceptions of Organizational Justice

To measure organizational justice perceptions, the researchers used the scale proposed by Colquitt [73]. The researchers used three sub-dimensions of the POJ scale to measure employee's perceptions regarding organizational justice. The three sub-dimensions are “Perceived Distributive Justice, Perceived Procedural Justice, and Perceived Interpersonal Justice”. The “Perceived Distributive Justice” consists of four items. The sample item is like this “Do the outcomes you receive reflect the effort you have put into your work?”. The Perceived Procedural Justice consists of seven items such as “Have you been able to express your views and feelings during those procedures?, Have you had influence over the outcomes arrived at by those procedures?”. Perceived Interpersonal Justice consist of four items such as “Has (he/she) treated you in a polite manner?, Has (he/she) treated you with dignity?”. All the items were asked to the respondents on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). The Cronbach's alpha value of the perceived distributive justice scale was 0.946. For perceived procedural justice, it was 0.955, and for perceived interpersonal justice, the Cronbach's alpha value was 0.971.

3.1.4. Organizational Citizenship Behaviour

To measure organizational citizenship behavior, the researchers used the scale proposed by Podsakoff et al. [74]. The scale consists of five sub-dimensions (“conscientiousness, sportsmanship, civic virtue, courtesy and altruism”). The conscientiousness sub-scale consists of five statements such as “Attendance at work is above the norm, Obeys company rules and regulations even when no one is watching”. The sportsmanship sub-scale consists of five statements such as “Always focuses on what's wrong, rather than the positive side (R), Always finds fault with what the organization is doing (R)”. The civic virtue sub-scale consists of four statements such as “Attends functions that are not required, but help the company image, Reads and keeps up with organization announcements, memos, and so on”. The courtesy sub-scale consists of five statements such as “Is mindful of how his/her behavior affects other people's jobs, Tries to avoid creating problems for coworkers”. The last sub-dimension, “altruism” consists of five statements such as “Helps others who have heavy workloads, Willingly helps others who have work-related problems”. All the items of the OCB scale were asked to the respondents on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). The Cronbach's alpha value of the “conscientiousness” scale was 0.857, for “sportsmanship” it was 0.853, for “civic virtue” it was 0.923, for “courtesy” it was 0.897, and for “altruism” the value of Cronbach's alpha was 0.875.

3.1.5. Employee Well-Being

To measure employee well-being, two scales were used. The first scale was related to satisfaction with life [75], and the second scale was related to the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) [76]. The scale “satisfaction with life” consists of five statements such as “In most ways my life is close to my ideal, The conditions of my life are excellent”. The Cronbach's alpha value of the SWL scale was 0.931 The PANAS scale consists of two subscales (positive affect and negative affect). The “positive affect” consists of ten statements such as “Enthusiastic, Interested, Determined, Excited, Inspired”. The “negative affect” consists of ten statements such as “Afraid, Upset, Distressed, Jittery, Nervous”. The Cronbach's alpha value of “positive affect” scale was 0.940, and for “negative affect” the Cronbach's alpha value was 0.957. All the items of the employee well-being scale were asked to the respondents on a five-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”).

3.2. Data Collection

The present study data were collected from employees who were working in the FMCD industry in India. The data were collected from Pan India. The sampling technique used for selecting the sample was random sampling. Before collecting the data, the respondents were assured about the confidentiality of the data and they were assured that the collected data will only be use for academic purposes. Participation in the study was voluntary and no incentives were given to any participant for their participation. Their consent was also taken to collect the data. The data were collected from 656 employees. The questionnaire was sent to 1124 employees, and 716 employees responded to the questionnaire, and finally, 656 useable questionnaires were utilized after removing 60 responses due to unengaged responses. There were 607 males and 49 females. 40.4% of the responses were less than the age of 35 years. 31.1% of the employees were in the age group of 35 to 40 years and the rests were above 40 years of age. 50.6% of the employees were either MBA or equivalent to MBA. 17.7% of the employees were graduates (B.E/B.Tech/Engineer). 50.5% of the employees were in sales and marketing. 46.6% of the employees worked in India's north region and 23.6% of the employees were working in the south region of India. Refer to Table 1 for further details.

| Variables | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 607 |

| Female | 49 | |

| Age | Less than 25 | 8 |

| 25 to 30 | 89 | |

| 31 to 35 | 168 | |

| 36 to 40 | 204 | |

| 41 to 45 | 136 | |

| 46 to 55 | 48 | |

| 56 to 60 | 3 | |

| Qualification | Graduate (B.E/B.Tech/Engineer) | 116 |

| Graduate (B.A/B.Com/B.Sc) | 95 | |

| Post Graduate (M.A/M.Sc/M.Com) | 80 | |

| MBA or Equivalent | 332 | |

| Diploma | 24 | |

| Other | 9 | |

| Functional Area | Administration | 35 |

| Finance & Accounts | 50 | |

| Sales & Marketing | 331 | |

| Logistics | 36 | |

| Human Resource | 38 | |

| Customer Service | 80 | |

| Legal/Compliance | 17 | |

| IT | 42 | |

| Quality Assurance | 18 | |

| Software Development | 9 | |

| Working Region (India) | East | 51 |

| West | 90 | |

| North | 306 | |

| South | 155 | |

| Central | 54 | |

4. RESULTS

Initially, exploratory factor analysis was performed to extract the distinct factors related to different constructs (POJ, EE, EW, OCB, and TI). After extracting the factors, confirmatory factor analysis was performed to validate the factors. After validating the factors, the next step is to test the proposed hypothesis. To test the hypotheses, the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) technique was applied.

4.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

An EFA was applied to extract the factors based on 73 statements. However, before applying the EFA, the researchers examined the sampling adequacy using the values of KMO (“Kaiser- Meyer Olkin”) and “Bartlett's test of sphericity”. According to Kaiser and Rice [77], a value of 0.6 or more for KMO means that the sample is adequate, and “Bartlett's test of sphericity” check whether the correlation matrix is identical or not. If the p-value of “Bartlett's test of Sphericity” is less than 0.05, then the null hypothesis is rejected, and it is concluded that the correlation matrix is not identical. If we fulfill these two conditions, then it means that we can perform the EFA to extract the factors. The EFA results show that the value of KMO was 0.832, which is more than the cutoff value of 0.6, and the p-value of “Bartlett’s test of Sphericity” was less than 0.05. A principal component analysis method with the “varimax” rotation method was used to extract the factors based on an eigen value higher than 1. The items whose factor loading was less than 0.5 were suppressed. The EFA results render fifteen distinct factors named as “perceived distributive justice, perceived procedural justice, perceived interpersonal justice (perceived organizational justice), emotional, behavioural, cognitive (employee engagement), conscientiousness, sportsmanship, civic virtue, courtesy, altruism (organizational citizenship behaviour), employee’s turnover intentions, satisfaction with life, positive affect, and negative affect (subjective wellbeing)”. In total, these fifteen factors explained 73.099% of the total variance. The standardized factor loadings of all the statements were higher than 0.5. This indicates that the results of EFA were satisfactory.

4.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

After extracting the factors with the help of EFA, a CFA was performed to validate the extracted factors. For this, a higher-order measurement model is drawn to check the reliability, validity, and model fit of the proposed hypothesized model. Therefore, a measurement model was drawn by covarying the higher-order measure of employee engagement, perceptions of organizational justice and organizational citizenship, and zero-order measure of employee turnover intentions, satisfaction with life, positive affect, and negative affect. After establishing the validity of the measurement model, the factors were imputed by using the regression imputation method. The convergent validity was discussed under Table 2 and discriminant validity was discussed under Table 3.

| Construct | Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional | ← | Engagement | .751 | .117 | 6.574 | *** |

| Behavioral | ← | Engagement | .936 | .134 | 8.350 | *** |

| Cognitive | ← | Engagement | .880 | _a | NA | NA |

| Distributive | ← | Justice | .838 | .030 | 30.956 | *** |

| Procedural | ← | Justice | .916 | _a | NA | NA |

| Interpersonal | ← | Justice | .910 | .018 | 47.740 | *** |

| Conscientiousness | ← | OCB | .744 | _a | NA | NA |

| Sportsmanship | ← | OCB | .758 | .048 | 19.864 | *** |

| Civic | ← | OCB | .840 | .034 | 28.493 | *** |

| Courtesy | ← | OCB | .722 | .041 | 20.306 | *** |

| Altruism | ← | OCB | .746 | .052 | 18.870 | *** |

| TI1 | ← | Turnover | .773 | _a | NA | NA |

| TI2 | ← | Turnover | .763 | .053 | 19.341 | *** |

| TI3 | ← | Turnover | .773 | .051 | 19.603 | *** |

| SWL5 | ← | SWL | .682 | _a | NA | NA |

| SWL4 | ← | SWL | .751 | .050 | 22.953 | *** |

| SWL3 | ← | SWL | .796 | .052 | 23.543 | *** |

| SWL2 | ← | SWL | .962 | .065 | 22.041 | *** |

| SWL1 | ← | SWL | .930 | .067 | 21.716 | *** |

| PA9 | ← | PA | .778 | .046 | 21.932 | *** |

| PA8 | ← | PA | .811 | .048 | 23.119 | *** |

| PA7 | ← | PA | .796 | .044 | 22.591 | *** |

| PA6 | ← | PA | .850 | .047 | 24.601 | *** |

| PA5 | ← | PA | .853 | .044 | 24.721 | *** |

| PA4 | ← | PA | .802 | .042 | 22.814 | *** |

| PA3 | ← | PA | .833 | .046 | 23.950 | *** |

| PA2 | ← | PA | .853 | .045 | 24.715 | *** |

| PA1 | ← | PA | .784 | _a | NA | NA |

| NA10 | ← | NA | .715 | _a | NA | NA |

| NA9 | ← | NA | .839 | .046 | 25.320 | *** |

| NA8 | ← | NA | .902 | .054 | 22.816 | *** |

| NA7 | ← | NA | .782 | .054 | 19.753 | *** |

| NA6 | ← | NA | .819 | .048 | 24.639 | *** |

| NA5 | ← | NA | .867 | .055 | 21.894 | *** |

| NA4 | ← | NA | .892 | .054 | 22.565 | *** |

| NA3 | ← | NA | .769 | .056 | 19.405 | *** |

| NA2 | ← | NA | .847 | .054 | 21.426 | *** |

| NA1 | ← | NA | .835 | .053 | 21.098 | *** |

| Construct | CR | AVE | EE | ETI | POJ | OCB | PA | SWL | NA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EE | 0.893 | 0.738 | 0.859 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ETI | 0.813 | 0.592 | -0.214 | 0.769 | - | - | - | - | - |

| POJ | 0.918 | 0.789 | 0.198 | -0.049 | 0.888 | - | - | - | - |

| OCB | 0.874 | 0.582 | 0.323 | -0.142 | 0.161 | 0.763 | - | - | - |

| PA | 0.948 | 0.670 | 0.176 | -0.418 | 0.138 | 0.264 | 0.818 | - | - |

| SWL | 0.917 | 0.691 | 0.324 | 0.238 | 0.207 | 0.412 | 0.008 | 0.831 | - |

| NA | 0.956 | 0.686 | -0.274 | 0.312 | -0.361 | -0.335 | -0.292 | 0.022 | 0.829 |

To determine the measurement model's convergent validity, the procedure mentioned by Fornell and Larcker [78] was used in the current study. At the initial step, the value of Standardized Regression Weights (SRW) were checked. The measurement model (Table 2) shows that the SRW of each variable is higher than 0.7 except for one variable, SWL5, whose SRW was 0.682. However, on average, the SRW for Satisfaction With Life (SWL) factor was higher than 0.70, and hence a decision was taken to retain the SWL5 variable. Results of measurement model also show that all the value of SRW was significant at 0.01 level of the interval. This shows the presence of convergent validity. In the next stage, the values of Composite Reliability (CR) and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) were compared to establish the convergent validity. As per the rule, CR's value should be higher than 0.70, and the value of AVE should be higher than 0.5. Finally, the value of CR should be greater than the value of the AVE of each factor. Table 3 shows that CR's value is greater than the value of the AVE of each factor. Hence, this ensures the presence of convergent validity.

Discriminant validity indicates that there is no association between the various constructions, and a system is unique and distinctive by catching phenomena not seen by other constructs [79]. According to the Hair et al. [79] method, discriminant validity was evaluated, which suggested that the inter-construct correlation coefficient should be lower than the square root of AVE of the corresponding factor. The bold diagonal values of Table 3 represent the square-root of AVE of each factor, and the off-diagonal value represents the inter-construct correlation coefficients. Results of Table 3 show that the diagonal value is higher than the off-diagonal values. This indicates the presence of discriminant validity in the measurement model.

Further, the model fit indices result depicted the presence of good model indices as the value of RMSEA was 0.052, CFI was 0.987, TLI was 0.984, and SRMR was 0.024. All the values of model fit indices show a good model fit.

4.3. Structural Model

The Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) technique was utilized to examine the inter-relationship among the proposed conceptual model with AMOS software's help. Before testing the proposed relationships, the assumptions of SEM were tested. Initially, the normality of the data was checked through the values of skewness and kurtosis. Results of the descriptive analysis show that all the statements have skewness and kurtosis values within the cutoff value of ±2 [80]. The data were then checked for multivariate outliers through the Mahalanobis method, based on the results of Mahalanobis. Results of the analysis show that there was no issue of multivariate outliers in the present data set. Hence, the researchers can perform SEM, for the testing of the hypotheses. To check the proposed hypotheses, the researcher draws a causal relationship between one exogenous variable (POJ), one mediator (EE), and five endogenous variables (SWL, PA, NA, OCB, and TI). Further, to examine the mediating effect of EE on the proposed relationships, the current study used bootstrapping technique by taking sampling at 2000 with a confidence interval of 95%.

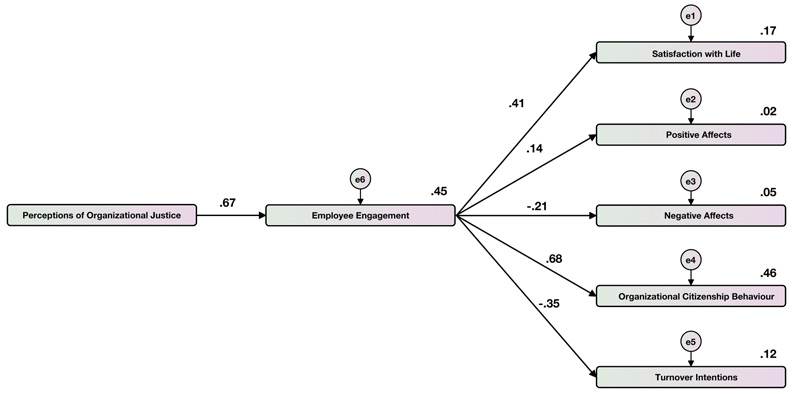

Results of structural equation modeling (Fig. 2) show that Perceptions of Organizational Justice positively impact Employee Engagement. Results show that the standardized beta for this relationship is 0.668, and it is significant at a 0.01 level of the confidence interval. It means that when an employee perceives justice at the workplace, it leads to high employee engagement. Hence, H1 was supported. The path analysis results show that perceptions of organizational justice have a significant impact on satisfaction with life as the p-value for this relationship is less than 0.01. Hence, H2(a) was supported. A similar type of result was observed for the relationship between perceptions of organizational justice and positive affect. Results show that there is a significant impact of perceptions of organizational justice on positive affect. Hence, H2(b) was supported. The path analysis results show that perceptions of organizational justice have a significant impact on negative affect as the p-value for this relationship is less than 0.01. Hence, H2(c) was supported.

Further, the results of Table 4 depict that employee engagement positively impacts organizational citizenship behavior. Results show that the standardized beta for this relationship is 0.678, and it is significant at a 0.01 level of the confidence interval. It means that when an employee has a high level of engagement towards work and organization, it leads to extra-role behavior. Hence, H3 was supported. Further, the path analysis results show that employee engagement has a significant and negative impact on employee’s intentions to leave the organization. Results show that the standardized beta for this relationship is -.345, and it is significant at a 0.01 level of the confidence interval. Hence, H4 was supported.

The mediation analysis (Table 5) shows that EE mediates the relationship between POJ and satisfaction with life. Hence, H8(a) was supported. A similar result was observed, where EE mediates the relationship between POJ and positive affect. Therefore, H8(b) was supported. Results of the mediation analysis show that EE mediates the relationship between POJ and negative affect. Hence, H8(c) was supported. In addition to this, the mediation analysis results show that EE mediates the relationship between POJ and OCB. Therefore, H8(d) was supported. Finally, the mediation analysis results show that EE mediates the relationship between POJ and employee turnover intentions. Hence, H8(e) was supported.

| Relationship | SFL | S.E. | C.R. | R-Square | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1 | Employee Engagement | <-- | Perceptions of Organizational Justice | 0.668 | 0.032 | 22.986 | 0.446 | *** |

| H2(a) | Satisfaction with Life | <-- | Employee Engagement | 0.414 | 0.039 | 11.646 | 0.172 | *** |

| H2(b) | Positive Affect | <-- | Employee Engagement | 0.135 | 0.071 | 3.496 | 0.018 | *** |

| H2(c) | Negative Affect | <-- | Employee Engagement | -0.214 | 0.071 | -5.593 | 0.046 | *** |

| H3 | Organizational Citizenship Behaviour | <-- | Employee Engagement | 0.678 | 0.024 | 23.578 | 0.459 | *** |

| H4 | Turnover Intention | <-- | Employee Engagement | -0.345 | 0.056 | -9.415 | 0.119 | *** |

| - | Relationship | Indirect Standardized Estimate | P-value | Direct Standardized Estimate | P-value | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H8(a) | Perceptions of Organizational Justice→ Employee Engagement→ Satisfaction with Life | 0.277 | 0.001 | 0.414 | 0.001 | Mediation |

| H8(b) | Perceptions of Organizational Justice→ Employee Engagement→ Positive Affect | 0.09 | 0.001 | 0.135 | 0.001 | Mediation |

| H8(c) | Perceptions of Organizational Justice→ Employee Engagement→ Negative Affect | -0.143 | 0.001 | -0.214 | 0.001 | Mediation |

| H8(d) | Perceptions of Organizational Justice→ Employee Engagement→ Organizational Citizenship Behaviour | 0.453 | 0.001 | 0.678 | 0.001 | Mediation |

| H8(e) | Perceptions of Organizational Justice→ Employee Engagement→ Turnover Intentions | -0.231 | 0.001 | -0.345 | 0.002 | Mediation |

5. DISCUSSION

The present study has many theoretical implications. First, the present study identifies the key antecedents and consequences of employee engagement, especially in the FMCD industry of India. Further, the present study validates the scales developed to measure different constructs such as “perceptions of organizational justice, employee engagement, employee well-being, organizational citizenship behavior, and employee turnover intentions”. This strengthens the existing pool of knowledge related to employee engagement and factors affecting employee engagement, and the possible consequences of employee engagement, especially in the context of India's FMCD industry. Further, the current study has various managerial and practical implications. This study examines the interrelationship among “perceptions of organizational justice, employee engagement, employee well-being, organizational citizenship behavior, and employee turnover intentions”. The study's findings postulated that the employee’s perception regarding the distribution of resources plays a vital role in affecting their engagement level. Further, the study also demonstrated that when an employer uses fair procedures to distribute the resources at the workplace, it has a positive effect on the employee engagement level. Further, the employer/supervisor's interpersonal skills also play an essential role in affecting the employee’s perception regarding engagement. Hence, the perceptions of organizational justice are an important factor that affects employee engagement. Accordingly, a manager should formulate such rules and policies in the organization, which enhance the employee’s perception regarding fairness in the distribution of resources among employees. Further, the results of the present study postulate that employee engagement affects employee well-being at the workplace. A highly engaged employee will also have a low intention to leave an organization. The present study also postulates that when an employee has a high level of engagement towards an organization, they perform extra-role to better their organization. They speak good things about their organization and run the extra mile for the betterment of their organization. Therefore, a manager should give utmost importance to handling the factors that affect an employee's engagement level as employee engagement has various severe consequences for an organization.

CONCLUSION

The findings of the current study come with some limitations which need to be discussed so that future researchers could avoid those limitations. The first limitation of the study is related to the cross-sectional research design. Due to this type of research design, it is not possible to establish the causal relationship among the tested variables. Hence, future researchers are suggested to follow a longitudinal research design to form a causal relationship among the variables. The second limitation is related to data collection. As the data were collected in a self-reported manner, hence there might be an issue of common method bias in the study. To check the effect of CMB, the researcher performed Harman’s Single Factor analysis and the results of the study show that there was no issue of CMB in the current study. Another limitation is related to the nature of the generalization of the results. As the data were collected from a single sector (FMCD), hence the findings of the study may not be applicable to other sectors. Future researchers are suggested to repeat the current study to other sectors to increase the generalizations of the results.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No Animals were used in this research. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from the participants.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.