All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Examining the Influence of Self-compassion Education and Training Upon Parents and Families When Caring for their Children: A Systematic Review

Abstract

Background:

It is well-recognized that early parenting significantly influences the health and well-being of children. However, many parents struggle with the daily demands of being a parent and feel overwhelmed and exhausted psychologically and physically. Encouraging self-care practices is essential for parents, and self-compassion may be a potential strategy to utilize.

Objectives:

The review aims to assess the influence and impact of providing self-compassion education for parents and families when caring for their children.

Methods:

This systematic review utilized Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) methodology. A three-stage search approach was undertaken that included seven electronic databases, registries and websites. These databases are Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Emcare, Cochrane library, Scopus, and ProQuest. The included studies were appraised using the standardized critical appraisal instruments for evidence of effectiveness developed by JBI.

Results:

Ten studies met the inclusion criteria. Overall, the studies confirmed improved psychological well-being, and higher levels of self-compassion, kindness towards oneself and others, and mindfulness were reported. In addition, there were improvements in psychological well-being, decreased parental distress and perceived distress, lower levels of anxiety, and avoidance of negative experiences.

Conclusion:

The findings provide evidence to guide further research on developing, designing, facilitating, and evaluating self-compassion education programs and workshops for parents and families.

PROSPERO registration

This systematic review title is registered at the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews: CRD42021225021.

1. INTRODUCTION

It is well-recognized that early parenting significantly influences the health and well-being of both children and their parents [1]. Experiencing challenges during early parenting may negatively affect the quality of parenting, parent-child relationship and attachment, and ultimately, the mental health and well-being of parents and their children [2]. Furthermore, parents with a child with developmental or intellectual disabilities, such as autism, report higher levels of distress and daily stressors associated with their children's disorders compared to parents without children with these disabilities [3, 4]. It has been proposed that self-compassion as a psychological intervention might support parents' mental well-being.

Self-compassion is not a new concept, having been embedded in Buddhist philosophy and practised for over 2500 years. Contemporary research on self-compassion has increased significantly due to its positive impact on mental well-being [5]. Strauss and colleagues provide a comprehensive definition of self-compassion as; “a cognitive, affective, and behavioral process consisting of the following five elements that refer to both self and other-compassion: 1) Recognizing suffering; 2) Understanding the universality of suffering in human experience; 3) Feeling empathy for the person suffering and connecting with the distress (emotional resonance); 4) Tolerating uncomfortable feelings aroused in response to the suffering person (e.g., distress, anger, fear) so remaining open to and accepting of the person suffering; 5) Motivation to act/acting to alleviate suffering” [6].

Self-compassion has been described as having three components. Each of the three components has a constraining positive and negative aspect [7]. The positive aspects are self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness. The negative components are self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification. Self-kindness relates to being supportive, gentle, and caring to oneself during a distressful life experience rather than self-judgment and criticism. Common humanity acknowledges and recognizes that everyone is suffering and experiences hardship during their lives rather than being the only one and isolating oneself from others. Mindfulness involves being aware of painful thoughts and negative emotions without avoiding or ignoring them and accepting them to help the healing process [4, 7, 8]. Therefore, each of the three components of self-compassion constitutes sets of both positive and negative cognitions and behaviours. To develop self-compassion as a wellbeing strategy, the focus needs to be on the positive components (self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness) rather than the negative aspects (self-judgment, isolation, and over-identification) [4, 7, 8].

Research exploring self-compassion have reported that self-compassion acts as a buffer against negative emotions and feelings and helps maintain psychological well-being, and promotes resilience [9-12]. Studies have also discussed the importance of self-compassion in different populations in reducing levels of anxiety, stress, negative emotions, and more severe mental health conditions such as depression. For example, there was a relationship between the level of self-compassion and emotional wellbeing and psychological distress in adolescents [13-15]. Furthermore, self-compassion reduced the strength of the relationship between maladaptive perfectionism and depression in adolescents and adults [10, 16]. Additionally, another study reported that having a high level of self-compassion was associated with improved sleeping patterns and resilience in health professionals such as nurses, dieticians, physicians, and social workers [14, 17]. Most commonly, self-compassion has been measured using the self-compassion scale (SCS), initially developed by Neff [18]. However, there are different versions and adaptations of this scale [19].

More recently, self-compassion has been adopted as an intervention within parenting programs [1]. It has been suggested that self-compassion may help parents develop acceptance and a more compassionate response to their children's behaviors and negative emotions [4]. Additionally, self-compassion education has been shown to decrease parental distress and thus improve well-being [3]. Previous studies have discussed the link between the level of self-compassion and mindful parenting [20-22]. These studies reported that a higher level of self-compassion was associated with a higher level of mindful parenting, lower level of parenting stress and lower levels of authoritarian and permissive parenting styles.

Furthermore, self-compassion was positively correlated with different domains such as affective, cognitive patterns, achievement and social connections, and networking [5]. Moreira et al. [22] highlighted the importance of developing and designing parenting education programs to reduce parenting stress and help parents become more compassionate toward themselves and others. It is recognized that peer support helps parents remain psychologically well and promotes positive parenting behaviors [23]. Taylor et al. [23] reported that parents who received peer support demonstrated positive parenting skills and the ability to monitor their children and children's social competence. Therefore, it would be reasonable to suggest that parents may benefit from education and training on self-compassion to develop coping strategies to respond more positively to potential stressors and be compassionate to their children.

There appears to be limited evidence to support the use of therapeutic approaches to increase individual self-compassion as an effective intervention to improve parental mental well-being and, consequently, the child's well-being [1, 24, 25]. Therefore, there is justification to undertake a systematic review to investigate the impact of self-compassion on parents' health and well-being when caring for their children.

2. REVIEW METHODS

2.1. Objective

To assess the impact of providing self-compassion education or training for parents and/or families when caring for their children.

2.2. Review Questions

(1) What is the impact of providing self-compassion education and training to parents and/or families when caring for their children?

(2) How do self-compassion education and training influence parents' and families' health and well-being?

(3) Does having the ability to give self-compassion assist parents in caring for themselves and their children?

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

The eligible studies met all of the following criteria:

- Type of studies: All types of studies, published or unpublished quantitative and mixed methods studies were included. Articles were restricted to the English language only and published after 2000. Studies that included any self-compassion scale used for evaluation and at least two components of self-compassion were recorded as outcomes.

- Type of participants: Target population (parents, mothers, fathers, family or families, and adoptive parents) of any age or gender who received education or training about self-compassion. Participants were described as parents, caregivers or guardians, or adoptive parents, and they had one or more children aged from (one month to 18 years). Children of the parents included may or may not have any behavioural, cognitive, or mental disability or special needs. Participants may have received the intervention in any setting (schools, primary or secondary community centres, rehabilitation centres, service agencies, primary or secondary mental health care centres, and hospitals).

- Type of interventions: All self-compassion studies where the intervention described the inclusion of self-compassion training provided for participants in any form of education, training, programs, workshops, or sessions targeted were included. These interventions were stand-alone or other interventions in any form or means of education (through face-to-face, one-to-one, group work, webinar, digital or online programs). In addition, these interventions were provided by any health professionals or qualified or trained educators (health workers, social workers/counsellors, psychologists, nurses, midwives, meditation practitioners, and mindful trainers).

- Type of outcomes included: Self-compassion measured by any validated or non-validated tools, participants' health, and well-being after receiving self-compassion training or education.

Excluded studies criteria:

- Self-compassion studies with no training or education (i.e., protocol trials, reviews, abstracts with no full text).

- Self-compassion education for all other populations (i.e., health professionals).

- Qualitative studies and theses.

- Studies that discussed one component of self-compassion, such as mindfulness alone

- Studies that discussed empathy or meditation.

2.4. Information Sources

A comprehensive search of several resources was undertaken to maximize the inclusion of all relevant studies. The systematic review protocol has been published that describes in detail the methodology [26].

2.5. Search Strategy

The search strategy was designed to find published and unpublished studies from the time period 2000 until January 2021. In total, seven electronic databases, registries and websites were searched. These databases were Medline, Embase, PsycINFO, Emcare, Cochrane library, Scopus and ProQuest. A three-step search strategy approach was conducted as recommended by Tufanaru et al. [27].

2.6. Selection Process

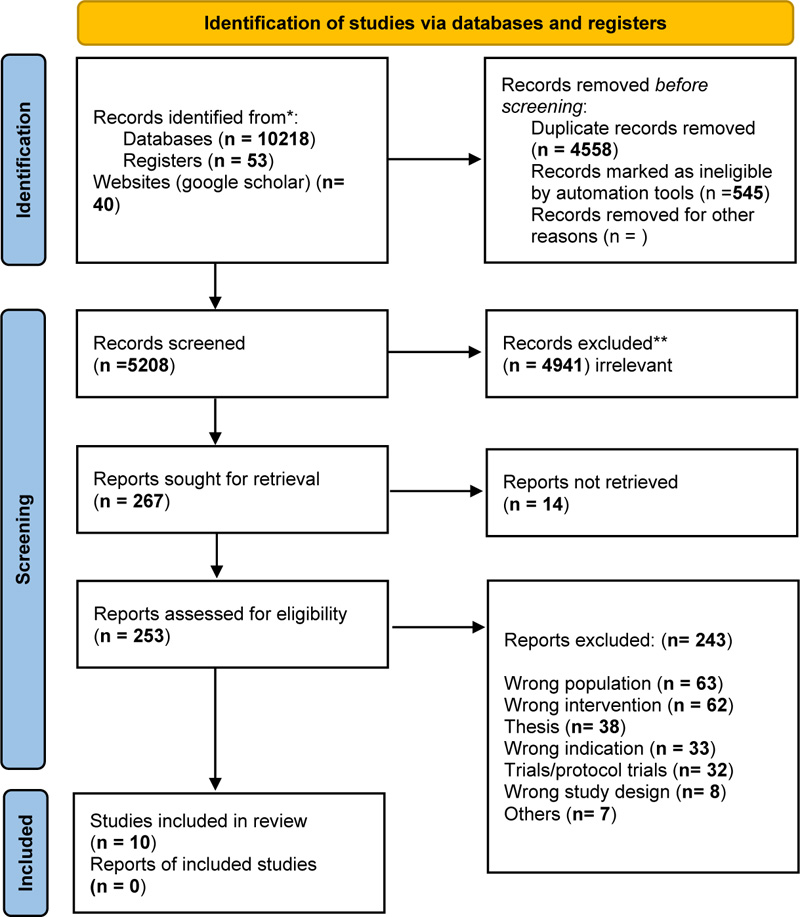

Review authors downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by the electronic databases search strategy into EndNote (citation management software). Duplicate records were identified, manually reviewed, removed, and uploaded into Covidence software (systematic review software). Two review authors (SO, DW) independently screened the titles and abstracts for assessment against the inclusion criteria for the review. The fulltext of the studies that met the inclusion criteria were retrieved and then imported into Covidence software. The full text of the identified studies was further assessed against the inclusion criteria with a third reviewer (MS). Full-text studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded based on a discussion involving two authors (SO, MS). Any disagreement was discussed until a consensus was reached as to whether to include or exclude a study. The review was guided by The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [28]. See (Fig. 1) PRISMA flowchart.

2.7. Data Collection Process

The first author (SO) extracted data from included studies and utilized a data extraction form used in an early review [29]. This data extraction form included study characteristics, including study citation, country, design, methods, settings, and population. This form also collected data on scales used to measure self-compassion, education and/or training program, findings, authors' conclusion, and recommendations. The extracted information was then checked and reviewed by a second review author (MS). No disagreement was found between the two review authors. Due to the clinical heterogeneity of the included studies (i.e., interventions, population, study designs, settings, different self-compassion scales, and outcome measures), a meta-analysis could not be conducted. Therefore, the findings are presented in a narrative format. (See Data Extraction Table 1).

2.8. Assessment of Methodological Quality and Critical Appraisal and Risk of Bias

Two review authors assessed and critically appraised all identified studies (SO, MS) for their methodological quality to be included in the review. The Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI) and (JBI critical appraisal checklist for randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental studies) standardized appraisal tools were used to critique identified studies [27]. Any study assessed as being low-quality of evidence would be excluded at this stage. However, all included studies were assessed as having a high-quality level of evidence (level 1 and 2) and achieved “YES” for at least 69% of the assessment checklist questions. (See Critical Appraisal of the included studies, (Tables 2 and 3).

|

Citation/ Country |

Type of Study/Design & Methods | Sample (Settings) | Aim | Self-compassion Measures | Education and Training | Findings Explored | Conclusion and Recommendations | Limitations/Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Bazzano et al. 2015) USA. |

Feasibility study (a single-group pre-/post- design). Self-administered questionnaires completed at three-time points: before program, immediately after, two months after completion. |

76 participants provided consent and attended the first session. However, only 66 parents and primary caregivers completed pre-and post-program questionnaires. Study was conducted at a local non-profit agency. |

To develop, implement, evaluate feasibility of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program, which was adapted for parents and caregivers who have individuals with developmental disabilities using a community-based participatory research (CBPR) framework. To assess the effect of MBSR program on stress, mindful awareness, self-compassion and psychological well-being. |

Self-compassion scale included 26 items (Neff 2003). All classes were taught by an experienced, trained MBSR teacher. Qualified Spanish translators in coordination with live simultaneous translation of each session. |

A pre-/post- evaluation of participants’ attending eight-week MBSR program for parents/caregivers of children with developmental disabilities. Participants had flexibility to attend different daytime options, on-site childcare, taxi vouchers, and practice CDs in English or Spanish. All services and incentives were provided free of charge. Training MBSR program consisted of eight weekly 2-h sessions and a four h silent retreat. MBSR program, including teaching mindful meditation practices, gentle yoga/movement, mindfulness and stress theory, and group discussion. |

Pre-/post-test data was only analyzed for minimum participation of four sessions. Most participants (60%) cared for individuals diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders, individuals diagnosed with intellectual disability (21%). Findings showed improvements in mindfulness, self-compassion, and psychological well-being. Self-compassion Scores improved significantly after the intervention (19 %) (P≤0.001) and after two months of follow-up (20 %) (P≤0.001). There was a significant decrease in parental stress (22%) and perceived stress (33%) following the intervention. Psychological well-being improved significantly (9 %) after intervention. Self-compassion scale scores show significant positive correlations with social connectedness, emotional intelligence, and life satisfaction, and significant negative correlations with self-criticism, perfectionism, depression and anxiety were observed. |

MBSR program was feasible and effective to reduce stress and improve stress-related outcomes for parents and caregivers of individuals with developmental disabilities. |

Study did not have a control group, the participants were self-selected. Not generalizable. RCT suggested to assess the impact on child/children Further studies to replicate findings and to assess impact of mindfulness intervention on parents and their children with development disabilities. |

| - | - | - | - | - | Meditation practices included awareness of breathing, body scan, a loving-kindness intention practice, and other exercises. Group discussion included topics related to parents' and caregivers' everyday stressors, their role, perception, and feeling about the child's future, practicing mindfulness with child, and feeling compassion toward themselves. The half-day retreat included the extended practice of various meditations, stretching techniques. Participants received information handbooks, printed assignments for each week, including instructions re; daily 30 minutes mindfulness exercises and two audio CDs with guided meditations and exercises. After completing program, participants were requested to write their feedback about program. |

- | - | - |

| (Benn et al. 2012), USA |

Pilot RCT, 3-time points assessment: One week before the program, one week after, and 2 months after completion. |

70 participants were randomly assigned to receive mindfulness training (MT) over the summer for the treatment group or the waitlist control group in the fall. Of them, 60 completed the baseline assessment; of them, 25 parents were assigned for (n=12 treatment group and n=13 control group). At school district. |

To assess efficacy of – 5 week mindfulness training(MT) program for parents and educators of children with special needs. |

Self-compassion scale consisting of 26-items was used (Neff 2003). Items measuring self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindful ness, and over-identification. Two instructors facilitated each MT group, who have professional training in mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program or mindfulness-based cognitive therapy after they received training by SMART (Stress Management and Relaxation Techniques) curriculum developers. |

Mindfulness training followed SMART-in-Education (Stress Management and Relaxation Techniques) program and 70% of the components and practices were similar to the mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program. Additional contents focused on emotion theory and regulation, forgiveness, kindness and compassion, and mindfulness application to parenting and teaching. The program also included activities, group discussions, mindfulness practices, and homework assignments. |

Immediately after the training: parents in the treatment group reported higher levels of stress, more depressive symptoms, and less self-compassion than the educators. While two months later, there were no group differences, except for self-compassion, as parents reported a significantly lower level of self-compassion than the educators. There was a significant and a strong relationship between mindfulness and self-compassion at baseline. Parents showed a significantly increased level of forgiveness after training than before. Self-compassion did not affect the well-being, anxiety, stress, and personal growth of the participants. Participants reported a reduction in distress, positive psychological functioning, greater self-compassion over time, more Empathy and forgiveness, and more awareness of their mental processes. Parents reported being more patient and emotional self-regulation. |

Participants had different strategies for stress reduction, which could be applied to their caregivers at home. The training program was efficacious over time and feasible for participants. Mindful training program significantly improved stress and anxiety levels, increased self-compassion and decreased negative mood states for both participants, with a significant reduction of stress and anxiety during follow-up. |

Findings based on self-reported data. Small sample size, low response rate. Passive waitlist control group rather than an active waitlist control group. All participants were paid $25 to complete study assessments at each of three-time points. Recruitment bias. Using several scales (14) which were too long to complete for the participants. |

| - | - | - | - | - |

MT sessions were administered twice a week over a 5-week period which delivered over eleven sessions (nine 2.5-hr sessions and 2 full days). Mindfulness practices included specific mental training exercises, i.e. concentration on thoughts or breath, and homework assignments, such as assignments of practicing sitting daily and monitoring emotional and behavioral responses. Each session included question-and-answer periods, lectures and group discussions, mindfulness practices, and group mindfulness practice. Session seven discussed compassion and kindness, including different activities, mindful stretching awareness of breath, sounds, sensations, thoughts, emotions, mental states, kindness and compassion discussion, focusing eyes on exercise, kindness meditation. |

- | - | - |

| (Gurney-Smith et al. 2017) UK |

A pre-/post- evaluation study design | Two groups: (11 staff members, 17 adoptive parents (6 adoptive fathers and 11 adoptive mothers). Adoption plus Agency. |

To describe the process of using Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT) as an intervention in addressing parenting stress in adoptive parents. |

Self-compassion scale-short form (Raes et al. 2011). It comprises 12-items that represent six components: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness and over-identification. Fully qualified mindfulness provided the training practitioner to deliver MBCT one day a week. |

Participants received an information sheet about mindful parenting and the intervention which might help with the parenting process. The staff working at the agency also received education about mindfulness. The researchers prepared a mindfulness-based stress reduction program in case of compassion and fatigue among staff. The whole course consisted of eight- sessions of interventions facilitated over many weeks. The first four sessions consisted of basic information about mindfulness, developing awareness of body sensations and mental activity, and encouraging daily home practice. After that, the four sessions focused on thoughts and feelings and reactive responses. The second four sessions focused on how to relate to negative emotions and accept them. It also identifies the unhelpful feeling, strategies, and individual actions to improve their well-being. |

After completing the program, the adoptive parents showed statistically significant differences in self-compassion scores increased at post-training (p<.05). The adoptive parents who have children reported statistically significant improvements in total parent stress score, defensive responding, parental distress, and perceived difficult child domains. For prospective and adoptive parents, there was an improvement in mindful attention, awareness, and self-compassion. |

The findings supported recommending and using the MBCT to the staff and parents within the adoption plus agency. The results support the widespread of using MBCT and its acceptability. It also was a flexible, practical, cost-efficient intervention for parenting stress and wide-reaching. |

This study is a pre-post study; however, it is not very well designed nor presented. A small number of participants and the absence of a control group. |

| (Kirby & Baldwin 2018) AUS |

Group-based, randomized-micro trial design. |

Participants were randomly assigned to receive (loving-kindness meditation (LKM) as experiment group or a Focused Imagery (FI) task as a control group). 61 parents with at least one child (2–12 years) completed the study. Only 43 participants completed the LKM exercise. The parents had healthy children (non-clinical group). Participants were recruited through the University of Queensland's research participation scheme. |

To examine the efficacy of loving-kindness meditation (LKM) in parenting and its influence on parenting practices. |

The self-compassion scale: a 26-items (Neff 2003), representing six subscales: self-kindness, self-judgment, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness and over-identification. The fears of compassion scale: a 15-item scale measuring participants' fear of giving compassion to themselves. The compassion motivation scale: an 11-items. The compassion to others scale: a 24-item that measuring the three subscales: kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness. |

The control group received the FI exercise. The experiment group: received an information sheet and were invited to sit at a computer in a group-based laboratory after giving their informed consent to participate. Used headphones to listen to the audio recording embedded in the online questionnaire. First, participants completed a set of preliminary questionnaires (demographic questions, parenting scale, fear of compassion, and self-compassion scales), then they were randomly assigned to one of the two audio-guided recordings that lasted for 15 minutes. Thirdly, they received the study questionnaires (self-compassion scale, compassion scale, compassion motivation scale, and parent-child vignettes). |

Participants who received the LKM had a higher score of motivation for self-compassion, and they found the audio recording to make them feel more compassionate (M= 7.52, SD = 1.03) than the FI exercise (M= 6.30, SD = 1.51), P = .001. Participants who received the LKM had a higher score of self-compassion (M=3.19, SD= 0.68) than those in FI (M=2.81, SD=0.57), p<.011. Participants in the LKM condition scored higher on motivation for self compassion (M=4.06, SD=0.49) when compared to FI (M=3.53, SD=0.88), p.010, for the control group. Participants in LKM scored higher on measures of compassion (M= 4.06, SD = 0.49) than those in FI (M= 3.53, SD = 0.88), p< .026, however, this is not statistically significant difference. |

The study concluded that parents reported high levels of acceptability with LKM. The study's authors suggested including it in evidence-based parenting interventions to support parents' well-being and becoming less reactive to children's distress, and increase their ability to feel more compassionate to their children. | This study is the first to use LKM within the parenting context. Limitations: The generalizability and durability of findings cannot be guaranteed for different cohort groups. Self-reported measurement scales were used. Future research for parents experiencing distress such as depression or parents of children with behavioral problems needs to be conducted. |

| - | - | - | - | - | Finally, they completed the manipulation checks and social desirability scale questionnaires. After the study was completed, the control group offered to complete the LKM exercise. Then, both groups completed the acceptability questionnaire. At completion, all participants received a debriefing sheet. The LKM exercise included six steps: mindful focus on breathing, directing the phrases (to oneself, to a person that makes them smile, to a stranger, to someone they dislike, and finally, directing phrases to a group such as family, community, or all humanity. |

The majority of parents reported that the LKM exercise is acceptable and valuable. LKM had an appositive effect on the parents' feelings. However, parents' cognitive and behavioral responses did not significantly change. Parents in the FI exercise showed significantly lower levels of calmness and higher levels of frustration and anger than parents in the LKM exercise. There was a significant positive correlation between fear of compassion and maladaptive parenting styles and child behavior. |

The study concluded that parents reported high levels of acceptability with LKM. The study's authors suggested including it in evidence-based parenting interventions to support parents' well-being and becoming less reactive to children's distress, and increase their ability to feel more compassionate to their children. | This study is the first to use LKM within the parenting context. Limitations: The generalizability and durability of findings cannot be guaranteed for different cohort groups. Self-reported measurement scales were used. Future research for parents experiencing distress such as depression or parents of children with behavioral problems needs to be conducted. |

| (Leung & Khor 2017) Hong Kong |

A Quasi-experimental Design (Non-randomized control group pretest/post-test design) |

637 parents completed the recruitment form and the pre-group questionnaire. Only 184 were selected (92 allocated to the intervention group, 92 allocated to the waitlist control group). Only 76 completed the intervention group, while 80 were at the waitlist control group. The parents had healthy children (non-clinical group). At Primary schools. |

To examine the therapeutic effectiveness of gestalt intervention groups for anxious parents who had children studying in grades 3-6. | Self-compassion scale (Neff, 2003) to assess self-kindness versus self-judgment. Item responses were measured on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). |

The intervention group activities included: mindful breathing, sensing activities, using sand tray activities, body scan, mutual sharing, artwork, and two-chair work. The intervention was administered as one weekly session for four weeks, and each session was 2 hours in duration. Mindful breathing was practiced at all sessions. The self-compassion theme was conveyed to the participants at all sessions, especially the third and fourth sessions through artwork and breathing exercises involving self-appreciation. |

The intervention group had a statistically significantly lower level of anxiety than the control group during post-test scores (P=.007). The intervention group showed a significantly lower level of avoidance of their inner experiences (P = .008), however, there was no significant difference in the control group (P = .794). The intervention group reported an increased level of kindness towards oneself and mindfulness (P=.009, P=.003) respectively; however, there was no significant difference in the control group (P=.218, (P=.429) respectively. Moreover, self-judgment scores were not statistically significant. |

The findings showed that the intervention group participants had a slight decrease in their level of anxiety and avoidance, while the self-kindness and mindfulness were improved. Culture sensitivity should be considered when using this therapy. |

The generalisability cannot be undertaken. Participants were intentionally allocated to the intervention and the control groups (no randomization). Lack of longer follow-up to assess the impact of interventions in reducing anxiety over time. |

| (Navab, Dehghani & Salehi 2019) Iran |

A quasi-experimental, pretest/post-test design with a control group. The correspondence author was contacted for more information about the self-compassion scale with no response. |

20 mothers of children with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were randomly assigned to the treatment group or the control group. At Health Centres of Isfahan City. |

To determine the effect of compassion-focused group therapy (CFT) on psychological symptoms of mothers of children who have attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). |

The DASS-21 questionnaire that consisted of three subscales (depression, anxiety and stress) with 21 items. The CFT was provided by a psychologist who had completed full-time CFT training for one year. The authors did not report measuring self-compassion. |

Before the intervention was started, both groups were asked to complete the pretest questionnaire. The treatment group received eight intervention sessions, once weekly lasting for 90 min. The waitlist control group received the intervention after the treatment group received it. Both treatment and the control group completed the post-test questionnaire one week after the completion of the intervention. |

During the post-test, participants in the treatment group showed a decreased level of anxiety and depression after attending the CFT, which were statistically significantly lower than the control group participants. However, there were no significant changes in the level of stress. The participants showed a high level of compassion toward self and others, associated with increased psychological well-being. |

The study provided an example of using CFT as a treatment method for the mothers of ADHD children to improve their depression and anxiety levels. Group-based therapy was used to enable the participants to share their feelings with others and to find support. Using this CFT as a psychological intervention for mothers, combined with psychological and therapeutic treatments for their ADHD children, can improve the treatment process and enhance the family relationship. Mothers of ADHD children need long-term education programs and training to keep them with an optimal level of mental health. |

The findings cannot be generalized because of the small sample size. Further studies included many men and women from different cultures needing to be conducted to replicate the findings. |

| - | - | - | - | - |

The eight treatment sessions included the following activities: Session 1: warming up and introducing the general principles of CFT and discussing the differences between self-compassion and self-pity. Session 2: mindfulness training through using body scan and breathing exercises, introducing the components of compassion and compassion-focused brain systems, and practicing safe place imagery. Session 3: discussing the characteristics of affectionate individuals, experiencing kindness from others and developing warmth and kindness towards oneself, fostering the sense of human affiliation than self-destructive feelings. Session 4: reviewing the exercises of the previous session, encouraging participants to self-analyse and practicing affectionate self-image. Session 5: reviewing the previous session, completing the interview form of the gentle mind (the desire dimension) Session 6: reviewing the previous session, completing the interview form of the gentle mind (the healing dimension). Session 7: reviewing the previous session, writing compassionate letters to themselves and others, instructions on writing notes of their real daily situations, based on their compassion and performance in that situation Session 8: summarising and providing strategies to maintain compassionate ways and applying CFT in an everyday situation. Participants received homework at every session, excluding the first and last one. |

During the post-test, participants in the treatment group showed a decreased level of anxiety and depression after attending the CFT, which were statistically significantly lower than the control group participants. However, there were no significant changes in the level of stress. The participants showed a high level of compassion toward self and others, associated with increased psychological well-being. |

The study provided an example of using CFT as a treatment method for the mothers of ADHD children to improve their depression and anxiety levels. Group-based therapy was used to enable the participants to share their feelings with others and to find support. Using this CFT as a psychological intervention for mothers, combined with psychological and therapeutic treatments for their ADHD children, can improve the treatment process and enhance the family relationship. Mothers of ADHD children need long-term education programs and training to keep them with an optimal level of mental health. |

The findings cannot be generalized because of the small sample size. Further studies included many men and women from different cultures needing to be conducted to replicate the findings. |

| (Poehlmann-Tynan et al. 2020) USA |

RCT with two cohorts, including pre and post-assessments (one month after). | Thirty-nine parents of children (9 months to 5 years old) were randomly assigned to the intervention group (n=25 for CBCT offered in two cohorts) or waitlist control group (n = 14), including pre and post-assessments. In the first cohort, 14 parents were randomized to CBCT, and 14 parents were randomized to a waitlist control group. Control group participants from the first cohort were invited to participate in a second cohort of the intervention along with 11 new intervention parents. Recruitment was done through Campus-affiliated Preschools. |

To explore the effect of Cognitive- Based Compassion Training (CBCT) on parent and child physiological stress processes in families of infants and young children through (hair cortisol concentration (HCCs). |

Parental self-compassion scale: 24 items (Neff 2003). This scale assesses six sub-items (three positive and three negative). The hair sample was collected from parents and their children (through cutting 10 mg of hair closest to the scalp to assess the cortisol level using mass spectrometry) before and after the intervention. The assessments included self-report measures and video-recorded measures. The assessment was undertaken by a trained research assistant or intern in a university research lab. The CBCT was administered through certified teachers. |

The intervention group received a CBCT that lasted for 8-weeks (2 hours weekly), plus a mini-retreat (for a total of 20 hours of group instruction). Each session contains guided meditation for 20 to 30 min and group discussion and encouragement for daily meditation using the video recordings. Both cohorts had 20 hr of instruction. However, the first cohort group met (2 hours weekly for ten weeks), whereas the second cohort group met 2 hours weekly for eight weeks, plus a 4-hr mini-retreat). Each week discussed a different theme. Module 1: developing attention and stability of mind: introduction to compassion meditation techniques. Module 2: awareness of sensations, feelings, emotions, and reactions. Module 3: cultivating self-compassion. Module 4: cultivating equanimity, focused on thoughts and feelings regarding different categories of people. Module 5: developing appreciation and gratitude and practicing independence. Module 6: developing Empathy. Module 7: wishing and aspirational compassion and being happy and free from suffering. Module 8: active compassion for others. |

No statistically significant effect of CBCT was found on parent self-reported parenting stress or perceived physical symptoms of stress. However, there was a significant effect of CBCT on child physiological stress (children cortisol level). This was evidenced by the decreased level of cortisol of infants and children of parents in the CBCT group over time, compared to the increased cortisol level of infants and children of the parents in the control group over time. During group discussion, parents reported that they are feeling calmer in stressful situations, thinking and feeling differently with their children, including self-compassion and gratitude. However, these findings were not statistically significant differences. |

The findings recommended examining mechanisms of effects on child physiological stress, including compassion toward children and others and parents' compassion behaviors. It is crucial to examine and evaluate interventions that decrease stress in children and engage their parents in this process. |

Small sample size and limited generalisability. Limited measurement of cortisol level of children across a large age group range. A limited longer follow-up to examine practice time related to participant outcomes in the intervention group. Each family was paid $25 for completing the assessments at each time point. |

| (Potharst, Zeegers & Bögels 2021) Netherlands |

A quasi-experimental longitudinal design, with a waitlist, pretest, post-test, and follow-up (2 and 8-month) after the treatment. | Twenty-two mothers with toddlers (18 to 48 months old) were recruited; of them, only 18 completed the study. Secondary mental health care lefts. |

To evaluate the effects of Mindful with your toddler in mother–toddler relationship who were referred to a mental health clinic because of regulation difficulties (co-regulation problems and/or self-regulation problems of mother and/or child). Examples of regulation difficulties (maternal over-reactivity, separation anxiety/demandingness of the child, child sleeping and eating problems, and excessive crying). More than half of participants had a mental disorder (depression, anxiety disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder. |

Self-Compassion Scale (the 3-items) was used The three items represent the three different subscales: common humanity, overidentification, and self-judgment. The items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The training was facilitated by a mindfulness trainer and an Infant Mental Health (IMH) specialist. |

Waitlist assessment was conducted for five weeks before the training. Pretest assessment was undertaken one week before the training. Post-test was immediately after the training, and the follow-up assessments were at 2 months and 8 months after the training. The training program was nine weekly 2-h sessions, with a follow-up session nine weeks after the training only for mothers to meditate and share their experience. Toddlers only joined the training at the fifth session after their mothers received psychoeducation about the circle of security and comfort. During the first three sessions, mothers learn to apply mindfulness and acceptance, patience, and trust, with themselves. From session 5: mothers started practicing and applying awareness to themselves and their children and applying mindfulness in stressful situations. The toddlers and their mothers were welcomed with a song and received an explanation about the program, followed by formal meditation (mothers were invited to bring their attention to themselves only in moment they feel space to do so and when the child is secure in the situation). |

At post-test, mothers reported being more sensitive and accepting toward their child than the pretest. Child psychopathology had decreased immediately after and was maintained at 2- and 8-months follow-up. Significant improvement in child dysregulation at post-test, 2 months, and 8 month follow-up. No significant improvement of maternal functioning and maternal overactivity. However, there was a borderline significant improvement at post-test for parenting stress. |

This study provided evidence that being mindful with your toddler can improve maternal co-regulatory abilities, maternal self-regulation including self-compassion, and toddler self-regulation. | These findings need to be interpreted with caution. Small sample size and no randomization had an effect on drawing a conclusion. The majority of the participants received other forms of support during the training. |

| - | - | - | - | - | - |

At 2-month follow-up, parenting stress and sense of incompetence improved; however, this decreased at 8-month follow-up. Slightly significant improvement of mothers' internalizing psychopathology and was maintained over time at 2, 8 month follow-up. Maternal externalizing psychopathology only slightly improved at 8 mth follow-up. |

- | - |

| - | - | - | - | - | Training session included inquiry (reflect on mothers and their children experience), home practice, short break, and activity between mother and child. Mothers practiced watching meditation with a focus on their toddler. Session was ended with a goodbye song for all mother-child dyads. Immediately after training, participants completed multiple-choice questions, which was an adapted version of stress reduction program evaluation. Mothers were reminded of follow-up session after nine weeks of training. |

Compassion for child revealed no improvement, while there was improvement in nonjudgmental acceptance of parental functioning at 2-month follow-up only. Self-compassion was improved at post-test and the follow-up period. |

- | - |

| (Potharst et al. 2017) Netherlands |

A quasi-experimental longitudinal design with pre-test, post-test, follow-up (8-week, 1-year). |

44 mothers with their babies (0-18 months) recruited; of them, only 37 participated in study. Participants referred to mindful with your baby training due to maternal mental health Problems, parenting stress. Study was conducted at primary, secondary mental health care lefts. |

To examine effectiveness of mindful with your baby, an 8-week mindful parenting group training for mothers with their babies. | Self-Compassion Scale (3-items) Three items' subscales were: common humanity, overidentification, and self-judgment. Training was facilitated by a mindful trainer and an IMH specialist. |

Assessment was undertaken at four-time points: one week before the training, one week after the training, eight weeks after the training, and one year later. Training Mindful with your baby consisted of 8 weekly 2-h sessions and follow-up session after 8 weeks. Program adapted for mothers with babies based on mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) program and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT). All sessions were conducted with mothers and babies except first and fifth sessions. Mothers practiced awareness with babies, full attention to baby signals, and applying mindfulness in stressful situations during sessions. Session started with formal meditation (mothers close their eyes, focusing attention on their babies for 10 to 15 minutes, they open their eyes with full attention to check if their babies need anything, then they close their eyes again, focus on experience with their babies). Meditation followed by inquiry and group discussion about home practices and a break. Each session discussed different topics such as distance and closeness. Mothers practiced 3-minute breathing space during session. Home practices consist of handouts about mindfulness, formal and informal meditation, and mindful parenting exercises. Participants completed the post-test program evaluation. |

Participants showed a significant improvement in mindfulness, mindful parenting, and self-compassion during the training and were maintained over time at an 8-week follow-up period. However, at one year of follow-up, only mindfulness and self-compassion improved further. A gradual improvement was observed in maternal well-being, maternal psychopathology, and parenting confidence immediately after and during the follow-up (two measurements). |

Findings showed that the mindful of your baby is feasible and an acceptable program for mothers with infants who experience parenting stress. Mothers became more mindful, more compassionate towards themselves during training and during the follow-up at 8 weeks. |

No control group or waitlist conditions to control the conclusion. Participants were not randomized to participate in study. Some participants received other forms of psychological support during the training. Mothers completed all measurements. |

| - | - | - | - | - | - |

Maternal warm and negative behavior towards infant, especially responsivity and hostility, improved at post-test and follow-up measurements, while full attention and rejection did not improve. Regarding infant temperamental behavior, only infant positive affectivity/surgency was improved at post-test and 8 weeks of follow-up. Furthermore, mothers reported that their babies experienced improvement in positive affectivity. |

- | - |

| (Potharst et al. 2019) Netherlands |

RCT with an intervention group and waitlist control group (Randomized waitlist-controlled trial design) Study part of a previous longitudinal cohort study which commenced in 2014. |

Of, 209 mothers with elevated levels of parental stress were invited for participation. Only 76 women were included in current study and randomized to intervention group (n = 43) or waitlist group (n = 33). Only 37 and 30 mothers were included in analyses. Training conducted as online training. |

To examine the effectiveness of 8 weekly online sessions of mindful parenting training for mothers of young children who are experiencing elevated levels of parental stress. |

Self-compassion scale (the 3-items) The three items represent the three different subscales: common humanity, overidentification, and self-judgment. The training was developed by a mindful parenting specialist and an online intervention specialist. The training was developed by a mindful parenting specialist (EP), an online intervention specialist (VS). |

Participants were randomized before completing the pretest assessment. The intervention group participants were requested to complete 8 weeks of intervention within 10 weeks and to submit the post-test assessment after completing the intervention. This was followed by another 10 weeks as a follow-up after the intervention. The waitlist control group completed a waitlist assessment, followed by 10 weeks waiting period (at same time, intervention group completed training). Followed by waitlist control group completed pretest and started intervention training, followed by post-test assessment. Training based on Mindful Parenting training and Mindful with your toddler training. Each session (range - 35 to 50 min) of training discussed different theme: automatic stress reactions, beginner's mind, at home in your body, responsive versus reactive parenting, self-compassion, conflict and repair, boundaries, taking care of yourself, and mindful parenting. Sessions included (body scan/sitting/walking meditation and mindful movement exercises, i.e. visualization, information - how to deal with difficulties, psychoeducation, daily home practice including, formal meditation (10 to 20 minutes maximum), informal meditation mindful parenting practice. During training, parents practice awareness of experience when interacting with their children. Parents learnt to practice self-care by being kinder to themselves, this training self-directed. Self-compassion discussed in detail at session five, included exercises: sitting meditation, attention to sounds thoughts, reflection exercise about avoidance, Psychoeducation about self-compassion. Average meditation time range - 15 minutes per week for intervention group and 19 minutes per week fore waitlist control group. |

There was no significant difference between the intervention and waitlist control group in terms of parental stress. For the intervention group, there was a significant improvement in the parental role restriction over time. There was a significant improvement in over-reactive parenting discipline for the intervention group at post-test and follow-up compared to waitlist control group. Significant improvement found for self-compassion in intervention group at post-test, follow-up assessment. Waitlist control group reported similar improvement after they received intervention. Significant improvement of mother-reported child aggressive behavior for intervention group. Waitlist control group reported similar improvement after they received intervention. |

The online parenting training was effective, valuable, and easily accessible for mothers with an elevated level of parental stress. The Mindful parenting online training helped parents to react to themselves and their children differently. The limited meditation time affected the delayed improvement in parenting and the parent-child relationship. |

At the beginning of the study, the intervention group reported symptoms of depression and anxiety more than the control group. A low percentage of the eligible women participated in the study with low adherence to the intervention. Using self-reported measures at study. Study one of first studies to undertake randomization for intervention. |

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Quasi-Experimental studies | ||||||||||

| Author/year | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Score |

| (Bazzano et al. 2015) | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/9 |

| (Gurney-Smith et al. 2017) | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/9 |

| (Leung & Khor 2017) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/9 |

| (Navab, Dehghani & Salehi 2019) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 8/9 |

| (Potharst, Zeegers & Bögels 2021) | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/9 |

| (Potharst et al. 2017) | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 7/9 |

| JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Randomized controlled trials | ||||||||||||||

| Author/year | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 | Q11 | Q12 | Q13 | Score |

| (Benn et al. 2012) | Y | Y | Y | N | U | U | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 9/13 |

| (Kirby & Baldwin 2018) | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | U | Y | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10/13 |

| (Poehlmann-Tynan et al. 2020) | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10/13 |

| (Potharst et al. 2019) | Y | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 10/13 |

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study Selection

A total of 10311 articles resulted from searching seven databases, registries, and websites. After removing 4558 duplicates, 5753 articles were reviewed by the title and abstract, and 267 were eligible for full-text screening. At this stage of screening, 257 articles were excluded for the following reasons: wrong target population (n=63), wrong intervention (n=62), theses (n=38), wrong indication (n=33), ongoing trials/protocol trials (n=32), no full-text or included only a conference abstract (n=14), wrong study design (n=8) and others (n=7). Ten studies met the inclusion criteria. The study selection and search strategy were guided by the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) methodology [28] Fig. (1) PRISMA flowchart.

3.2. Study Characteristics

There was heterogeneity between the included studies' designs and methods. Of the ten included studies, four were pilot randomized controlled trials, group-based randomized micro-trials or randomized controlled trials or randomized controlled trials with two cohorts, and post-assessment and randomized waitlist-controlled trial design [30-33]. While the other six were quasi-experimental studies, including pre-, post-test evaluation study, or pre-, post-test study with a control group, longitudinal design with a waitlist, pre-test, post-test, and follow-up [34-39].

In terms of the country in which the studies were undertaken, three studies were conducted in the Netherlands and three in the United States. In addition, one study was located in the United Kingdom, one in Australia, one in Iran, and one in Hong Kong. All included studies were conducted between 2012 and 2021. Eight of the included articles mentioned the setting where the study was conducted. These studies were conducted at different settings; local non-profit agency [34], adoption agency [35], school district [30, 36], health centres [37] or primary or secondary mental health care centres [38, 39]. Only one study was conducted online [33]; (Table 1).

3.3. Participants' Characteristics

Participants from seven (70%) of the included studies were reported to have children requiring additional needs/support for developmental-behavioral disorders or relationship problems, i.e., developmental disabilities [34], children with special needs [30], or children with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [37]. Three studies (30%) involved parenting stress [33, 35, 38], and one study focused on the regulation and relationship difficulties of the mother and/or child [39]. Only three studies (30%) included participants and children having no additional challenges [31, 32, 36]. The parents, caregivers, or adoptive parents who participated in these studies were reported to have one or more children whose ages ranged from one month to 12 years old [31, 32, 36, 38, 39]. However, five studies did not report the children's age range [30, 33-35, 37].

The participants' sample size was different for every study. The four (40%) randomized controlled trials included a total of 183 parents or caregivers [30-33]. The six quasi-experimental studies included a total of 314 parents or caregivers who completed the questionnaires [34-39]. (See Data Extraction Table 1).

3.4. Self-compassion Scale used in the Included Studies

All included studies used different self-compassion scale types of measurements and evaluations. Four studies [33, 36, 38, 39] used the three components measured within the original self-compassion scale (SCS) developed by Neff and Germer [8]. Three studies used all of the 26-items of SCS, representing six subscales [30, 31, 34]. Kirby and Baldwin [31] used additional compassion scales; the fear of compassion scale, -15-items; the compassion motivation scale -11-items; and the compassion to others scale - 24-items. In addition, one study used 24 items for the SCS [32], and another study [35] used the short-version 12 items self-compassion scale [19]. Finally, one study [37] measured self-compassion and used the DASS-21 scale for three subscales (depression, anxiety, and stress) with 21 items. However, this study did not report a specific self-compassion scale being used, and the corresponding author was contacted with no response.

3.5. Who Provided the Training or Education?

The training or the education was provided through certified or trained specialists; an experienced and trained mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) teacher [34], instructors who have had professional training in the MBSR program, or mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) [30], a fully qualified mindfulness practitioner [35], a psychologist [37], certified teachers [32], and a mindfulness trainer and an Infant Mental Health (IMH) specialist [38, 39]. The training program, which was provided online, was developed by a mindful parenting specialist (EP) and an online intervention specialist (VS) [33]. However, two studies [31, 36] did not provide information on who delivered the education.

3.6. Self-compassion Training or Education (Type of Interventions)

All included studies provided a self-compassion education program or training to their participants. The program education or training package contained a mix of teaching activities and learning methods, including lectures, video recordings, group discussions, questions and answer periods, printed materials and handouts, interactive materials such as practice sessions, breathing exercises, daily home practices, and assignments. The majority of the included studies discussed self-compassion, active compassion for others, mindfulness practices, group mindfulness, mediation, awareness of sensations, appreciation, and gratitude.

Only four of the included studies designed their education and training programs based on mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) programs [30, 33, 34, 38]. All training programs for eight of the included studies had at least four sessions with a maximum of eleven sessions, and each session ranged between 35 minutes to 2 hours [32-39]. Except for two studies, participants received the training for eleven sessions that lasted between 2 and half hours and two full days [30], and a study received audio recordings for 15 minutes [31].

In terms of follow-up after providing the education program, four studies conducted longer follow-up periods between eight weeks and one year time [30, 34, 38, 39].

3.7. Effect of Self-compassion Training on Parents' Health and Well-being

After attending a self-compassion training program, most participants, including parents, caregivers, primary caregivers, or adoptive parents, showed improvement in psychological well-being, decreased parental distress and perceived distress, low level of anxiety, and a low level of anxiety avoidance of negative experiences. In addition, there was a statistically significant improvement in the participants' self-compassion scores, improved mindfulness, and increased level of kindness towards oneself and others [31, 33, 35, 36-39]. Furthermore, the self-compassion scale scores showed significant positive correlations with social connectedness, emotional intelligence, and life satisfaction (self-compassion level and psychological wellbeing were increased by 20% and 9%, respectively, following the program). In contrast, significant negative correlations with self-criticism, perfectionism, depression, and low anxiety were observed (27% reduction in perceived stress level following the program) [34]. For the studies with a longer follow-up, the participants had an improvement and maintained a higher level of self-compassion and psychological well-being over time. However, one study discussed that there was no correlation reported between these variables (self-compassion and well-being, anxiety, and stress) [30].

3.8. Effect of Self-compassion Training on Children

Only two studies reported the effect of providing self-compassion training on children and their parents [32]. Poehlmann-Tynan et al. [32] reported a significant impact of Cognitive Based Compassion Training (CBCT) on child physiological stress (children's cortisol level), evidenced by the decreased level of cortisol of infants and children of parents in the CBCT group over time ((mean = 54.26, SD= 95.16) for the intervention group, versus the control group (mean = 238.22, SD = 690.81)). In addition, parents reported feeling calmer in stressful situations and feeling differently with their children, including self-compassion and gratitude. Another study reported a decreased level of the child's psychopathology and improved dysregulation after attending the CBCT training [39].

4. DISCUSSION

Parenting can create significant anxiety and stress, with many parents struggling to cope with the expectations and daily demands of providing care and support to their child/children. Pollack (p. 24) [40], in reference to Freud, concluded that parenting is 'an impossible profession'. Acknowledging the innate challenges associated with parenting, this review sought to understand if self-compassion education could support parents in this role.

Being kind and compassionate to yourself has been largely overlooked as a self-care strategy [41]. A parent's inner voice is often self-critical and self-blaming. However, self-compassion can be cultivated to help parents accept that it is okay to not be perfect. The 'good enough mother' was a concept first recognized by Winnicott, a paediatrician and parent-infant therapist [42]. Therefore, the idea of 'good enough parenting' recognizes that parenting can take many forms and that there is no one 'right' way to parent. This concept advocates that parenting is 'good enough' when parents are able to provide sensitive and responsive care. Teaching parents to be self-compassionate may facilitate a more responsive approach to parenting and this may also assist parents in accepting their imperfections and acknowledging that it is normal to feel overwhelmed and that negative experiences are universal [40].

Of note, the majority of included studies explored parents with additional demands placed upon them, i.e., child/children with developmental and/or intellectual disabilities. While not the primary focus of this review, these studies clearly demonstrate that these parents experience higher levels of distress and daily stressors associated with their children's disorders and behaviours when compared with parents who do not have children with additional needs [3, 4]. For these parents, self-compassion education was beneficial as an intervention that decreased anxiety and supported their mental well-being. It would be valuable to undertake further research exploring the impact of self-compassion on parents who do not have additional needs to ascertain the degree of benefit of self-compassion education for a universal application.

A further finding that warrants discussion is the impact of self-compassion on improved social connectedness. Social support is a well-documented approach to promoting mental well-being [43-45]. Evidence demonstrates a clear link between maternal mental health and social networks, where the most connected mothers experience the best mental health outcomes [46]. Social relationships can reduce parenting stress, improve maternal well-being and self-efficacy, and buffer the experience of postpartum depression [47-49]. Exploring self-compassion in relation to social connectedness and its impact on perinatal well-being could be warranted.

Self-compassion has been studied broadly and there is now clear evidence that demonstrates the benefits of educating and training the mind of parents to be compassionate to self and others. In addition, self-compassion has health and well-being benefits for people in general [17]. There is also a growing body of evidence to suggest that self-compassion is related to positive health and well-being outcomes for several target populations, such as veterans [41]; nurses and midwives [50]; student nurses [51]. This review contributes further to this evidence, identifying that self-compassion education may be a strategy to support parental mental well-being.

Neff, (p140) [7] defined self-compassion as “being caring and compassionate towards oneself in the face of hardship or perceived inadequacy”. This definition clearly relates to the challenges of parenting, and self-compassion is generally considered to be an adaptive emotional regulation strategy to enhance self-care [52, 53]. Mindfulness is interwoven with the concept and practices of self-compassion and has its origins derived from Buddhist core teachings [54]. Many of the studies in this review used mindfulness-based approaches (MBA) such as MBSR, MBCT, and CFT, which focused on mindfulness-awareness and involved taking a balanced approach to negative emotions and neither suppressing nor exaggerating these and a willingness to acknowledge negative emotions with openness and clarity [41, 55]. There is emerging evidence linking self-compassion and mindfulness to neuroscientific changes in the brain [32, 56], which recently showed that cognitively based compassion training for parents reduced cortisol levels in infants and young children. This is an area to undertake further research.

In summary, the authors of this review draw on a quote from Pollack [40] (p24), who suggests that: 'mindfulness and compassion are not just practices for exhausted, stressed-out parents who are trying to juggle too many balls without dropping them all’, they are tools for life.

CONCLUSION

This review provides evidence that self-compassion education and training were beneficial for parents to reduce anxiety and promote positive well-being, particularly for parents who had a child requiring additional care and support. It is recommended that further research is undertaken to explore the impact of self-compassion education as a mental well-being strategy for all parents.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| SCS | = Self-Compassion Scale |

| PRISMA | = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| JBI-MAStARI | = Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument |

| ADHD | = Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder |

| MBSR | = Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction |

| MBCT | = Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy |

| CBCT | = Cognitive Based Compassion Training |

| SC | = Self-Compassion |

| MBA | = Mindfulness-Based Approaches |

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines were followed.

FUNDING

The authors would like to acknowledge the UniSA Sansom Institute, healthy families for a healthier relationship, for funding this systematic review.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We wish to confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Declared none.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

PRISMA checklist is available as supplementary material on the publisher’s website along with the published article.