All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Need-satisfaction as a Mediator of Teaching Style and School-Bullying Intentions

Abstract

Background

In response to the escalating incidents of bullying, the Indonesian government initiated the Roots Program. This program emphasizes the establishment of positive discipline through the involvement of teachers employing an authoritative teaching style.

Aim

This research aimed to analyze the role of teachers in shaping bullying intentions by employing a model based on the framework of the basic psychological needs theory.

Objective

The objective of this study was to explore the mediating effect of need satisfaction on the relationship between an authoritative teaching style and bullying intentions among high school students.

Methods

This study employed a correlational quantitative approach, utilizing convenience sampling to gather data from 396 high school and vocational school students. Data collection involved the use of three scales: the modified Bullying Intention Scale, the Indonesian version of TASCQ, and the Indonesian version of the BPNSFS Satisfaction subscale. Data analysis was conducted using PLS-SEM.

Results

The findings indicated that basic psychological need-satisfaction significantly mediates the relationship between authoritative teaching style and bullying intentions (β = -0.11, p<0.05, 95%CI = -0.17, -0.07). Although the relationship is significant, the effect of an authoritative teaching style on bullying intentions through the mediation of basic psychological need satisfaction remains weak.

Discussion

Consistent with the basic psychological needs theory framework, this study confirms the critical role of need satisfaction in promoting anti-bullying attitudes. Students who perceive their psychological needs being met through the implementation of an authoritative teaching style by teachers exhibit lower bullying intentions.

Conclusion

The study concludes that periodic assessments of the basic psychological need-satisfaction of students are essential for the sustainability of anti-bullying programs, thereby enhancing the effectiveness of such initiatives.

1. INTRODUCTION

Bullying incidents are on the rise in Indonesia, with the country now ranking fifth globally in the number of reported school bullying cases [1]. High school students aged 13-17 years experience the highest prevalence of bullying [2]. The consequences of bullying on teenage students are multifaceted, encompassing low self-esteem, fearfulness, social withdrawal, difficulty coping with failure, diminished motivation for learning, depression, and the potential transition to becoming perpetrators of bullying [3-7]. The roots of bullying are deeply intertwined with social-contextual factors, including authoritarian family dynamics, stressful home environments, the existence of corporal punishment within schools, peer dynamics, economic disparities, and exposure to media influences [8, 9]. Aligned with the understanding of these factors, the government has introduced the Roots Program, a school-based initiative aimed at curbing the prevalence of bullying. This program places significant emphasis on the pivotal roles of both peers and teachers in fostering a positive and anti-bullying climate within educational institutions [10].

Bullying intention is an individual's perception of the potential to cause harm to others physically, verbally, or psychologically by exploiting a power imbalance [11, 12]. As a primary environment for students, schools are responsible for cultivating a safe, peaceful, and sometimes prone-to-bullying environment [13, 14]. As a social component in school, the teachers were asked to demonstrate caring authority and use positive discipline to encourage anti-bullying as a social norm in school [15, 16]. Teachers can perform strategies, including interventions between students, mediating for both conflicted parties, and approaching the offenders to admit their fault and apologize [17]. Nevertheless, sometimes bullying in Indonesia is caused by teachers themselves who bully their students or ignore the signs of bullying behavior in school. The study of Ahyani et al. [18] found that the acts of bullying by teachers mostly took the form of physical violence and punishment when the student did not complete their task or came late to class. Subsequently, the bullying behavior shown by the teachers can be imitated by the students. Therefore, the Indonesian government has introduced the Roots Program, a school-based initiative to curb bullying, in which teachers are expected to implement positive discipline by eliminating physical and emotional punishment while also serving as a safe, comfortable, and open channel for students to report instances of bullying [10]. The desired teacher characteristics align with those of an authoritative teaching style. The authoritative teaching style is a pedagogical approach where students have the autonomy to determine learning goals and strategies. Moreover, they receive appreciation from the teacher for their feelings and perspectives, along with reinforcement to think independently and solve problems [19, 20].

While an authoritative teaching style itself may not inherently trigger bullying intentions, its underlying mechanisms require further exploration. Research on the mechanisms of bullying intentions among high school students in Indonesia remains scarce. In the past decade, studies predominantly focused on factors correlating with school bullying, such as school climate [21, 22], social support [23], and conformity [24]. However, there is a gap in research investigating the mechanisms through which school bullying intentions occur in Indonesia. While one national study employed a qualitative approach with an ecological theory perspective on preschool students [25], international research included three quantitative studies using the perspective of the basic psychological needs theory [26-28]. Nevertheless, these international studies only involved elementary to middle school students in China and Spain. Therefore, this study sought to analyze the mechanism of an authoritative teaching style in reducing bullying intentions among high school students, particularly those in schools implementing the Roots Program. We could not have drawn the conclusion from existing studies because of the cultural and cohort differences. The previous studies took place in Western (Spanyol) and Asian (China) cultures, which are different from Indonesian cultures. Western culture is oriented toward individual societies, while Asian culture is oriented toward collectivist societies. It makes important differences in the perpetrator (strangers vs. classmates), the environment (playground vs classroom), and the types of bullying (extortion vs social exclusion) [16, 29]. Although China and Indonesia were included in the same Asian culture, the study of Sittichai & Smith [30] found that there were different bullying-like phenomena in Southeast Asia, including Indonesia, that need to be studied more. Besides, the participants used in the previous studies involved elementary to middle school students, while this study involved high school students with different characteristics, such as the peak period when autonomy, relatedness, and competence are crucial to be fulfilled [31].

The researchers developed a theoretical model based on the Basic Psychological Needs Theory framework to explore this mechanism. This theory postulates bright functioning, which posits that a supportive environment contributes to positive growth and prevents malad- justment in individuals by satisfying basic psychological needs [32]. This theory is considered relevant because the peak prevalence of bullying occurs during adolescence (13-17 years), a period where fulfilling basic psychological needs, including autonomy, relatedness, and competence, is crucial [31, 33]. When these basic psychological needs are satisfied (need-satisfaction), individuals tend to experience healthy psychological development, which is manifested in intrinsic motivation for academic activities, prosocial behavior, and overall well-being at school [27, 34]. Aligned with a bright functioning postulate, the researchers worked with a full mediator model of an authoritative teaching style on bullying intention. Three hypotheses were tested in this study. First, we expected a negative relationship between an authoritative teaching style and bullying intentions through need-satisfaction as the central hypothesis (Hypothesis 1). The main hypothesis was formulated by combining the prior literature about relationships between authoritative teaching style and basic psychological needs-satisfaction and between basic psychological needs-satisfaction and bullying intentions. Due to prior literature, we expected that there was a positive relationship between authoritative teaching style and basic psychological need-satisfaction (Hypothesis 2), as stated in the study of Haerens et al. [35], especially in need for autonomy [36] and relatedness [37]. We also expected that there was a negative relationship between basic psychological need satisfaction and bullying intentions (Hypothesis 3). This prediction was supported by the studies of Santurio et al. [26] and Varsamis et al. [38], which found that need-satisfaction discourages maladaptive coping mechanisms, such as bullying. The theoretical model of this research is illustrated in Fig. (1).

The theoretical model of authoritative teaching style on bullying intentions through need-satisfaction.

2. METHOD

2.1. Design

This study employed a correlational quantitative design, encompassing dependent, independent, and mediator variables. Specifically, bullying intention was designated as the dependent variable, authoritative teaching style was the independent variable, and basic psychological need satisfaction functioned as the mediator variable.

2.2. Participants

The participants of the study were high school and vocational school students who had undergone the implementation of the Roots program in Kebumen Regency. The total population comprised 48,485 individuals. Employing the Slovin Formula with a significance level of 95%, a sample size of 396 participants was determined. The convenience sampling technique was utilized. The distribution of samples based on educational background, gender, age, and educational level is elucidated as follows: The collective sample included 104 (26.3%) high school students and 292 (73.7%) vocational school students. Within the sample, there were 19 (4.8%) male participants and 377 (95.2%) female participants, with ages ranging from 15 to 19 years and a mean age of 16.8. The educational level of the sample was relatively evenly distributed, with 130 (32.8%) 10th-grade students, 138 (34.9%) 11th-grade students, and 128 (32.3%) 12th-grade students.

2.3. Ethics

In accordance with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration, this research obtained ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee (KEPK) of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Muhammadiyah Surakarta, as indicated by Letter Number 4876/B.1/KEPK-FKUMS/VII/2023. Further- more, all participants filled out the informed consent forms before engaging in the research scale, ensuring their explicit approval and willingness to participate in this study.

2.4. Measures

2.4.1. Teacher as Social Context Questionnaire (TASCQ)

The authoritative teaching style was assessed using a modified version of the TASCQ scale, adapted for use in the Indonesian context [39]. This scale comprises 11 items that address three key aspects of the authoritative teaching style as proposed by Soenens et al. [20]: autonomy support (3 items), involvement (4 items), and structure (4 items). A higher score on this scale indicates a more positive perception of the authoritative teaching style implemented by the teacher. The modification process of the scale involved expert judgment to test the content validity and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The expert judgment yielded a V index ranging from 0.75 to 0.96. The CFA results (Table 1) revealed cross-loadings in the range of 0.74 to 0.85, with Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values of 0.86, 0.92, and 0.89, Composite Reliability (CR) values of 0.77, 0.91, and 0.83, and Cronbach's Alpha (CA) values of 0.76, 0.91, and 0.83. These findings affirm that the scale demonstrates convergent validity, discriminant validity, and construct reliability, making it suitable for measuring the authoritative teaching style construct.

2.4.2. Satisfaction Subscale of the Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale (BPNSFS)

Satisfaction of basic psychological needs was evaluated using a modified version of the BPNSFS satisfaction subscale, adapted for use in the Indonesian context [40]. This scale comprises 8 items that address three aspects of satisfying basic psychological needs, as proposed by Vansteenkiste and Ryan [32]: the need for autonomy (3 items), the need for competence (4 items), and the need for relatedness (1 item). A higher score on this scale indicates a greater satisfaction of the student's basic psychological needs. The scale modification process involved expert judgment to test the content validity and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). The expert judgment yielded a V index ranging from 0.75 to 0.89. The CFA results (Table 1) revealed cross-loadings in the range of 0.76 to 0.87, with Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values of 0.83, 0.88, and 1.00, Composite Reliability (CR) values of 0.70, 0.82, and 1.00, and Cronbach's Alpha (CA) values of 0.70, 0.82, and 1.00. These findings affirm that the scale demonstrates convergent validity, discriminant validity, and construct reliability, making it suitable for measuring the construct of satisfying basic psychological needs.

| Construct/Indicator | Item | Cross Loading | CA | Rho_A | CR | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritative Teaching Style | ||||||

| Autonomy Support | AS1 | 0.84 | 0.76 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.86 |

| AS2 | 0.85 | |||||

| AS4 | 0.78 | |||||

| Involvement | I1 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| I2 | 0.83 | |||||

| I3 | 0.81 | |||||

| I4 | 0.78 | |||||

| Structure | S2 | 0.74 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.89 |

| S5 | 0.76 | |||||

| S6 | 0.81 | |||||

| S7 | 0.84 | |||||

| Basic Psychological Need-satisfaction | ||||||

| Need for Autonomy | NA2 | 0.81 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.83 |

| NA3 | 0.77 | |||||

| NA4 | 0.78 | |||||

| Need for Competence | NC1 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.88 |

| NC2 | 0.84 | |||||

| NC3 | 0.76 | |||||

| NC4 | 0.81 | |||||

| Need for Relatedness | NR2 | 0,87 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Bullying Intention | ||||||

| Initial desire to hurt | IP1 | 0.81 | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.90 | 0.70 |

| IP2 | 0.86 | |||||

| IP3 | 0.73 | |||||

| Imbalance of power | DH1 | 0.75 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 0.84 | 0.64 |

| DH3 | 0.88 | |||||

| DH4 | 0.89 | |||||

| DH5 | 0.82 | |||||

| Typically repeated | R2 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.85 | 0.91 | 0.77 |

| R3 | 0.87 | |||||

| R4 | 0.86 | |||||

| R4 | 0.86 | - | ||||

Note: Table 1 shows only valid and reliable items that have been tested using expert judgement and CFA.

2.4.3. Bullying Intention Scale

Bullying intentions were assessed using a modified version of the Bullying Scale developed by Mansyur et al. [41]. This scale comprises 10 items that encapsulate three facets of bullying as proposed by Rigby [12]: the initial desire to inflict harm (3 items), an imbalance of power (4 items), and a pattern of repetition (3 items). A higher score on this scale indicates a greater propensity for a student to engage in bullying behavior. The modification process of the scale involved expert judgment to test the content validity and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Expert judgment yielded a V index ranging from 0.79 to 0.93. The CFA results (Table 1) revealed cross-loadings within a range of 0.73 to 0.90, Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values of 0.70, 0.64, and 0.77, Composite Reliability (CR) values of 0.90, 0.84, and 0.91, and Cronbach's Alpha (CA) values of 0.86, 0.72, and 0.85. Consequently, the scale is deemed to possess suitable convergent validity, discriminant validity, and construct reliability for measuring the construct of bullying intentions. The comprehensive confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of this study is delineated in Table 1.

| Parameter | Eligibility | Value | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| NFI | 0.19 weak; 0.33 moderate; 0.67 strong | 0.84 | Good |

| R Square | 0.19 weak; 0.33 moderate; 0.67 strong | 0.31 | Moderate |

| Path coefficient | All of p-value < 0.05 | 0.00 | Good |

| Q2 | Q2 > 0.00 | 0.33 | Good |

2.5. Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). This method was selected due to its ability to estimate the relationships between research variables, thereby enabling the prediction of the target construct based on the pre-established theoretical model (Fig. 1) [42]. The SEM analysis was performed using the SmartPLS 3.0 software.

3. RESULTS

Prior to hypothesis testing, the proposed model must first undergo a feasibility evaluation. The goodness-of-fit metric was used to assess the alignment between the theoretical model and the empirical data collected in the study. In PLS-SEM analysis, a model is deemed feasible if it satisfies the parameters for the Normed Fit Index (NFI), R Square, path coefficient, and Q2 [43]. The results of the goodness-of-fit test are presented in Table 2

An analysis of model suitability was conducted, as shown in Table 2, to assess the extent to which the Structural Equation Model (SEM) aligns with the available data. The goodness-of-fit indicators presented in Table 2 demonstrate that the model was constructed in accordance with empirical data.

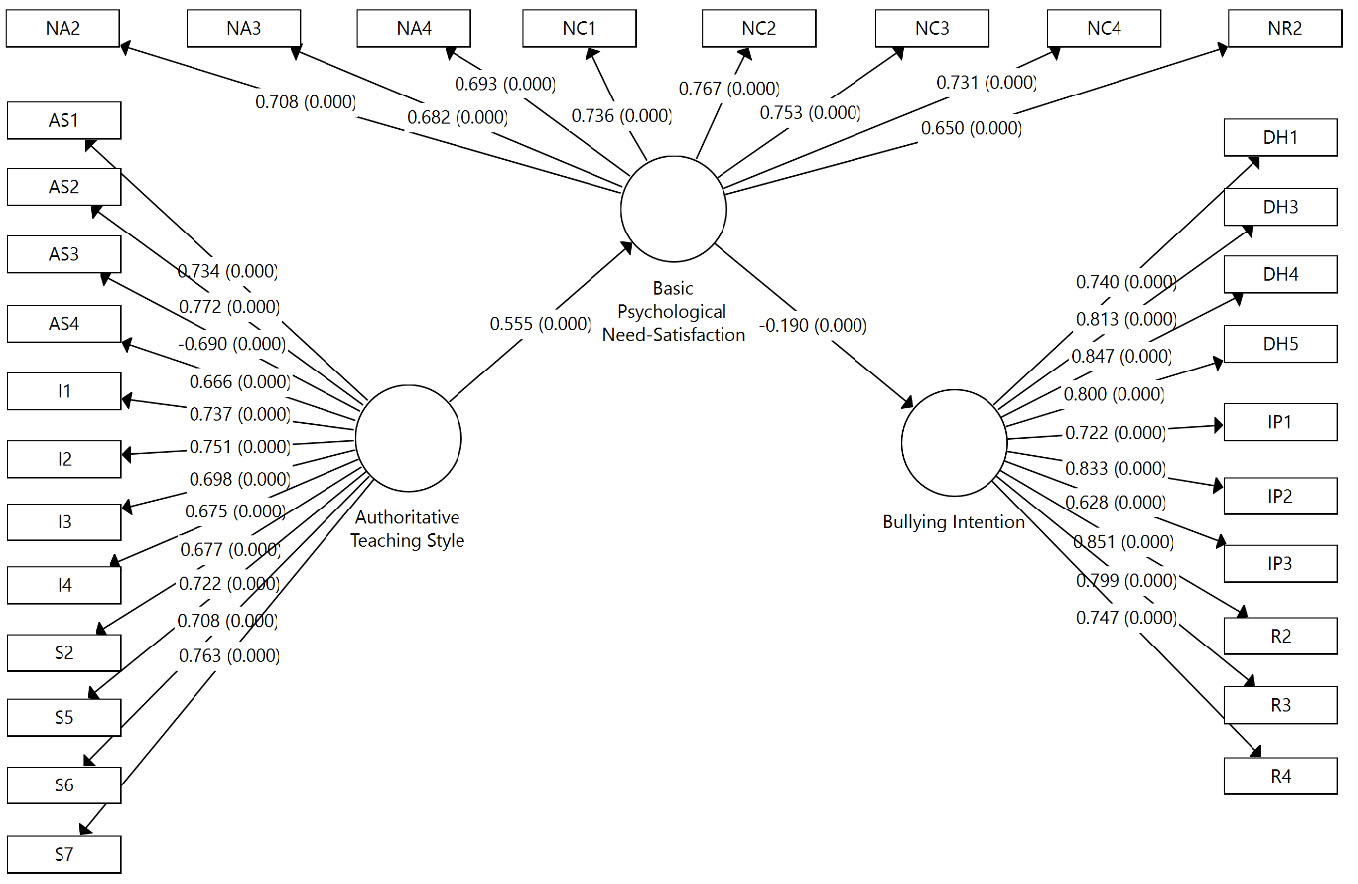

The analysis proceeded with the validation of three research hypotheses. Three hypotheses were examined: Hypothesis 1 investigated the relationship between an authoritative teaching style and bullying intentions, mediated by the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Hypothesis 2 aimed to establish a positive relationship between an authoritative teaching style and the satisfaction of basic psychological needs. Lastly, Hypothesis 3 sought to demonstrate a negative relationship between the satisfaction of basic psycho- logical needs and bullying intentions. The results of these hypothesis tests are presented in Fig. (2) and Table 3.

Full model of authoritative teaching style on bullying intentions through basic psychological need-satisfaction.

| - | Estimated Effect | t-value | p-value | PCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authoritative Teaching Style -> Need-Satisfaction -> Bullying Intention | -0.11 | 3.57 | 0.00 | [-0.17, -0.07] |

| Authoritative Teaching Style -> Need-Satisfaction | 0.55 | 16.50 | 0.00 | [0.50, 0.61] |

| Need-Satisfaction -> Bullying Intention | -0.19 | 3.78 | 0.00 | [-0.29, -0.13] |

Note: PCI: Percentile Confidence Interval; Bootstrapping based on n=10,000 bootstrap samples; Paths from hypothesized effects assessed by applying one-tailed test at 5% of significance level [5%, 95%].

A hypothesis is deemed accepted if the t-value exceeds 1.645 (t>1.645) and the p-value is less than 0.05 (p<0.05). Based on the hypothesis test results presented in Table 3, a significant but weak negative relationship was observed between authoritative teaching style and bullying intentions, mediated by the satisfaction of basic psychological needs (β = -0.11, t = 3.57, p < 0.05, 95%CI = -0.17, - 0.07). This significant correlation between the independent variable, mediator, and dependent variable further substantiates the mediating role. Consistent with this finding, a significant and moderate positive relationship was identified between an authoritative teaching style and the satisfaction of basic psychological needs (β = 0.55, t = 16.50, p < 0.05, 95%CI = 0.50, 0.61). Additionally, a significant but weak negative relationship was found between the satisfaction of basic psychological needs and bullying intentions (β = -0.19, t = 3.78, p < 0.05, 95%CI = -0.29, -0.13). Therefore, all research hypotheses were accepted. The estimated effect of bullying intention explained by authoritative teaching style through need satisfaction (β = -0.11) was smaller than the estimated effect explained directly by need satisfaction (β = -0.19). This means that basic psychological need satisfaction has a bigger effect than an authoritative teaching style in explaining bullying intentions; nonetheless, the effect remains weak.

4. DISCUSSION

The tested model was a full mediator model, which posited that without the satisfaction of basic needs, there would be no direct relationship between the influence of an authoritative teaching style and bullying intentions (Fig. 2). This model was constructed within the framework of the basic psychological needs theory. The model met all the goodness-of-fit parameters (Table 2), demonstrating a link between the theoretical model and empirical data. The model contributed a compelling 31% (R-Square value), suggesting that an authoritative teaching style, through the satisfaction of basic psychological needs, contributes to a 31% change in bullying intentions. The remaining 69% is attributed to other factors.

According to research hypothesis 1, it was found that an authoritative teaching style significantly correlates with bullying intentions through the mediation of basic psychological needs satisfaction. These findings confirm the postulates of the basic psychological needs theory regarding bright functioning, which posits that a supportive environment contributes to positive growth and prevents maladjustment in individuals through the satisfaction of basic psychological needs [32]. Previous research utilizing the basic psychological needs theory framework found that the satisfaction of essential psychological needs partially mediated the relationship, producing an estimated effect of -0.044 to 0.078 [28].

The research conducted by Montero-Carretero [28] used autonomy-supportive and controlled teaching styles as predictors and focused on elementary to middle school students aged 11-15 in Spain. In contrast, this study focused on an authoritative teaching style with a sample of high school and vocational school students in Indonesia. This study produced a more significant estimated effect of -0.11, which means basic psychological need satisfaction takes a bigger role in bullying intention among Indonesian high school students. Several other studies also support the effectiveness of basic psychological needs satisfaction as a mediator in Indonesian educational psychology research. This variable fully mediates the relationship between the quality of friendships and life satisfaction in adolescents [40] and partially mediates the relationship between lecturer support and academic buoyancy [44].

In line with the evidence regarding the complete mediation of basic psychological needs satisfaction, a positive and highly significant correlation was found between an authoritative teaching style and basic psychological needs satisfaction. Table 3 shows that these two variables correlate with a t-value above 1.645 and a p-value < 0.05 towards satisfying basic psychological needs, thus accepting H2. This implies that the more positively a student perceives the authoritative teaching style applied by the teacher, the more the student's basic psychological needs are satisfied.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT), the overarching theory of Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT), differentiates the social environment into need-supportive, need-depriving, and need-thwarting environments. Need-supportive environments are those where social agents support the satisfaction of basic psychological needs [32]. Schools are one of the determinants of achieving these conditions [45]. Consistent with the data processing results, previous research suggests a positive and significant correlation between an authoritative teaching style and basic psychological needs satisfaction [46, 47]. Teachers play a role in satisfying the basic needs of students through three aspects: autonomy, structural support, and teacher involvement in the academic activities of students [20]. Autonomy support encourages the satisfaction of the need for autonomy, structural support promotes the satisfaction of the need for competence, and teacher involvement encourages the satisfaction of the need for relatedness [48, 49]. Thus, these findings confirm the role of teachers as need-supportive agents in the Indonesian school environment, as targeted in Roots Program implementation.

The satisfaction of basic psychological needs will subsequently influence bullying intentions. Table 3 shows that these two variables have a negative and highly significant correlation with a t-value above 1.645 and a p-value < 0.05, thus accepting H3. This means that the more an individual's basic psychological needs are satisfied, the lower their bullying intentions will be. As stated by Vansteenkiste and Ryan [32], the satisfaction of basic psychological needs plays a vital role in building adaptive behavior and functioning positively in social life. Individuals with satisfied basic psychological needs will genuinely accept responsibility for social norms, values, or regulations. Bullying includes aggressive behavior and deviating from social norms. Therefore, individuals with satisfied basic psychological needs will accept the responsibility for social norms and not engage in bullying. This finding is aligned with the implementation of the Roots Program in Indonesia, utilizing social norms as a promising avenue to curb school bullying intention [15]. This finding is also supported by previous research, which found a negative correlation between satisfying the need for relatedness and autonomy to bullying intentions and antisocial behavior at school [27, 50].

5. IMPLICATION

5.1. Theoretical Implication

This research can contribute to the creation of an anti-bullying school environment. The bigger effect of basic psychological need-satisfaction than the authoritative teaching style in explaining bullying intention means that basic psychological needs satisfaction could enhance the effect of the authoritative teaching style. Utilizing the framework of the basic psychological needs theory, it can be concluded that bullying prevention programs must consider the psychological satisfaction of students to enhance the role of the school as the social component, such as an authoritative teaching style, in creating anti-bullying norms. Psychological satisfaction is a crucial step for adequate socialization, where it encourages students to not only externally obey a value performed by the teacher but also to reach the stage of internalizing that value with a complete sense of willingness and responsibility.

5.2. Practical Implication

In line with this, the satisfaction of basic psychological needs acts as a complete and significant mediator, meaning that the psychological satisfaction of students regarding the anti-bullying program and its implementing components can be one of the determinants of whether students will instill the values of the program being implemented and have a negative attitude towards bullying or vice versa. Therefore, the psychological satisfaction of students can be measured periodically regarding the implementation of anti-bullying programs in schools to encourage the effectiveness of instilling anti-bullying values in students.

6. LIMITATION

The limitation of this research is that the R-squared and estimated effect was relatively low. This could be due to the researchers not carrying out a more detailed identification and classification regarding the attitudes of students towards bullying. Given these limitations, future studies can identify and classify the attitudes of students towards bullying while conducting bullying research on the bullies, the victims, and the uninvolved people to obtain more specific and clear data.

CONCLUSION

Based on the research findings, it can be concluded that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs is a significant mediator in bridging the relationship between an authoritative teaching style and school bullying intentions. An authoritative teaching style will increase the satisfaction of students’ basic psychological needs, which will subsequently reduce bullying intentions. This research has implications for the implementation of the Roots Program, where it is necessary to periodically measure the psychological satisfaction of students regarding the role of teachers in implementing the anti-bullying program. Further, the psychological satisfaction of students can be one of the keys to successfully implementing the Roots Program and creating an anti-bullying school environment.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| TASQ | = Teacher as Social Context Questionnaire |

| CFA | = Confirmatory Factor Analysis |

| AVE | = Average Variance Extracted |

| CR | = Composite Reliability |

| CA | = Cronbach's Alpha |

| BPNSFS | = Satisfaction Subscale of Basic Need Satisfaction and Frustation Scale |

| PLS-SEM | = Partial Least Square Structural Equation Modeling |

| NFI | = Normed Fit Index |

| NA | = Need for Autonomy |

| NC | = Need for Competence |

| NR | = Need for Relatedness |

| AS | = Autonomy Suppor |

| NA | = Need for Autonomy |

| I | = Involvement |

| S | = Structure |

| DH | = Initial Desire to Hurt |

| IP | = Imbalance of Power |

| R | = Typically Repeated |

| SDT | = Seft-Determination Theory |

| BPNT | = Basic Psychological Needs Theory |

| KEPK | = Research Ethics Commite |

| LRI UMS | = Research and Innovation Institute of Universitas Muhammadiyah Surakarta |

ETHICAL STATEMENT

In accordance with the 1975 Helsinki Declaration, this research obtained ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee (KEPK) of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Muhammadiyah Surakarta, as indicated by Letter Number 4876/B.1/KEPK-FKUMS/VII/2023

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Informed consent was obtained from all participants to ensure their voluntary participation in this study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data and supportive information are available within the article.