All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

The Relationship between Loneliness and Disordered Eating Behaviors: The Impact of Gender and Relationship Status-A Cross-sectional Study

Abstract

Background

Loneliness and disordered eating behaviors have previously demonstrated an interrelated relationship. Loneliness arises from a gap in one’s desired relationships and meaningful connections. Disordered eating behaviors are irregular or unhealthy eating practices that can negatively affect one’s emotional and physical well-being. The primary aim of this research was to assess the direct association between feelings of loneliness and disordered eating behaviors among an overlooked population, Lebanese young adults. The study also assessed the moderating effect of gender and relationship status on this association.

Methods

In this study, 384 Lebanese young adults, male and female, aged 18-25, completed the UCLA Loneliness Scale, the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire, and a brief sociodemographic questionnaire. The primary methods used for data analysis were independent samples t-test, Pearson correlation coefficient, ANOVA, two-way ANOVA, and moderating regression analysis.

Results

The results demonstrated that higher levels of loneliness were significantly associated with increased overall disordered eating behaviors in both genders. Gender had a small but significant effect on the EDE-Q global scores, while relationship status influenced loneliness but not disordered eating behaviors. Overall, gender did not moderate this relationship, except in the case of higher shape concern among females. In addition, relationship status had no moderating effect, although individuals in a relationship reported significantly lower levels of loneliness in comparison to those who are single.

Conclusion

Based on the results of this study, it can be stated that feelings of loneliness have a significant impact on the development of disordered eating behaviors. This aligns with previous research while addressing a gap by exploring the association among Lebanese young adults. This research has shed light on possible trends between the two variables, with respect to gender and relationship status, offering insights for interventions and treatments in a context previously unexamined, particularly in the Middle East.

1. INTRODUCTION

Loneliness is a complex and subjective emotion experienced differently by each individual. It is an emotion that occurs when an individual perceives a gap in their desired relationships, whether in terms of quantity or quality [1]. This emotion can have significant effects on mental well-being [1], one of them being disordered eating behaviors. Eating disorders often intertwine with feelings of loneliness, demonstrating a complex interplay between one’s emotional state and eating behaviors. Eating disorders can be defined as persistent disruptions in eating or eating-related behaviors that result in significant impairments in physical health or psychosocial functioning [2]. In the present study, the eating disorders are not individually differentiated. This study focuses on the correlation between feelings of loneliness and disordered eating behaviors. Furthermore, this study assesses the impact of one’s gender and relationship status in relation to this association. Feelings of loneliness are complex and do not lend themselves easily to risk assumptions based on gender, as various studies have produced inconsistent findings. Several studies have reported significantly higher feelings of loneliness among females, and others have reported among males while some studies did not observe a significant relationship between loneliness and gender [3-6]. As for eating disorders, various associations have been observed between gender and disordered eating characteristics. Differences were found based on the type of disorder. For instance, orthorexia nervosa, body dissatisfaction, and emotional eating were found to be significantly higher among males [7]. However, for females, higher levels of restraint were observed, along with a significant correlation between body dissatisfaction and orthorexia nervosa [7]. Among females, body dissatisfaction was more strongly associated with compulsive exercise, as well as with weight control behaviors. Additionally, the avoidance of negative emotions was more strongly related to compulsive exercise [8]. However, among males, binge eating and muscle building were mostly associated with compulsive exercise [8]. Both genders demonstrated a significant positive correlation between body dissatisfaction and restraint eating, although this relationship was stronger among females [7]. Previous literature has assessed the effect of relationship status on feelings of loneliness and found that individuals in a relationship experience significantly less feelings of loneliness [9-12].

Studies have evaluated relationships between loneliness and eating disorders or their characteristics/behaviors. A significant positive correlation was found between social disconnectedness and eating disorders [13]. Patients diagnosed with an eating disorder reported significantly higher scores in loneliness and lower perceptions of social support [14, 15]. In addition, feelings of loneliness and negative mood were predictive of increased body dissatisfaction and increased urges for restrictive eating and overeating [16]. Higher levels of loneliness were associated with increased severity of eating disorder symptoms, while more frequent experiences of the anorexic voice were linked to a higher frequency of eating disorder symptoms [17]. Although previous literature has assessed the associations between loneliness and eating disorders, there remains a lack of focused research on these two variables. In addition, no prior studies have been conducted among a Middle Eastern population, including the Lebanese population.

1.1. The Present Study

The objective of this study was to assess the relationship between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors among Lebanese young adults while highlighting gender differences and the impact of one’s relationship status on this relationship. The hypotheses of this study are as follows: Hypothesis 1: There is a significant positive correlation between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors among Lebanese young adults (H1a), and more specifically, a significant and positive correlation to restraint (H1b), eating concern (H1c), shape concern (H1d), and weight concern (H1e). Hypothesis 2 proposes that gender moderates the relationship between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors, such that the relationship is stronger for females than for males. Hypothesis 3 suggests that relationship status moderates the relationship between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors, such that the relationship is stronger for single individuals than for those in a relationship. Following the hypotheses, this study aimed to fill the gap present in the literature by focusing solely on the two main variables: loneliness and disordered eating behaviors. It also assessed this relationship among an overlooked population, Lebanese young adults. Understanding this link can aid in the roles of professionals, such as nutritionists, psychiatrists, psychologists, and doctors, potentially leading to a more integrative approach to supporting individuals struggling with loneliness or an eating disorder. Treatment interventions and prevention strategies can be placed in accordance with the association.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Sample and Procedure

This cross-sectional study was conducted from March 2023 until March 2024. The total number of participants was 384, adhering to the minimal sample size to achieve a 5% interval of error (95% confidence interval). The minimal sample size was calculated using G*Power software.

Gender (male and female) was a key variable in the design, and participants were grouped by gender for data analysis. This study adhered to the SAGER (Sex and Gender Equity in Research) guidelines to ensure the appropriate consideration and reporting of sex/gender throughout the research process. The completed checklist is available in the supplementary materials.

The distribution of the questionnaire was done online through google forms due to the difficulty of displacement in Lebanon. Data collection involved the simple random sampling method [18]. The inclusion criteria for the study sample required all participants to be Lebanese young adults within the age range of 18-25 who met the criterion of being English speakers, as the questionnaire was administered in the English language. Participants who failed to meet the criteria or opted not to participate were deliberately excluded from the study.

2.2. Measures

A sociodemographic questionnaire was used to collect general information about the participants. Gender and relationship status were key variables in the study, being assessed as moderators of the association between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors. For this reason, participants were grouped by gender (male and female) for data analysis. Gender was differentiated based on the participants' self-reports.

2.2.1. Loneliness

Loneliness was measured using the 20-item UCLA Loneliness Scale version 3, developed by Russel et al. in 1978 [19]. It consists of 20 items that are rated on a Likert scale of 1-4 (1=never, 2=rarely, 3=sometimes, 4=often). A sample item is: “How often do you feel that you are in tune with the people around you?”. Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.89 to 0.94, suggesting strong internal consistency [20].

2.2.2. Disordered Eating Behaviors

The variable was evaluated using the 28-item Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q 6.0) developed by Fairburn et al. in 2008 [21]. The scale consists of 4 subscales: restraint, eating concern, shape concern, and weight concern while calculating a global score [21]. Furthermore, the scale is divided into 4 sections. A sample item of the first section is “Over the past 28 days, on how many days have you been deliberately trying to limit the amount of food you eat to influence your shape or weight (whether or not you have succeeded)?”, with response options ranging from 0 (no days) to 6 (every day) [21]. A sample item of the second section is “Over the past 28 days, on how many days have such episodes of overeating occurred (i.e., you have eaten an unusually large amount of food and have had a sense of loss of control at the time)?”, answered by writing a number [21].

As for the third section, a sample item is “Over the past 28 days, on how many days have you eaten in secret (i.e., furtively)? … Do not count episodes of binge eating”, ranked with the same scale of section 1 [21]. A sample item of the fourth section is “Over the past 28 days, on how many days has your weight influenced how you think about (judge) yourself as a person?”, with response options ranging from 0 (not at all) to 5 (markedly) [21]. Cronbach’s alpha ranges from 0.78 to 0.93 [22].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

The participants included in the study were Lebanese young adults aged 18-25 years old (n = 384). The majority were female (62.5%, n = 240); 36.5% (n = 140) were male, and 1% (n = 4) preferred not to disclose their gender.

Regarding the relationship status, 68.2% (n = 262) were single, 30.2% (n = 116) were in a relationship, and 1.6% were categorized as “other,” referring to married or divorced/separated.

Geographically, the sample included participants from all governorates in Lebanon. Table 1 shows the mean and standard deviation of each variable. The mean score for loneliness (M = 2.4025, SD = 9.79) suggests a moderate level of loneliness on average among participants. For labeling purposes in the table, loneliness is labeled as “UCLA”, restraint as “EDE-Q1”, eating concern as “EDE-Q2”, shape concern as “EDE-Q3, weight concern as “EDE-Q4”, and global score as “EDE-Q5”. This strategy is used in all the following tables of the article.

3.2. The Association between Loneliness and Disordered Eating Behaviors

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to assess the strength and direction of the associations between the variables. Correlation coefficients are demonstrated in Table 1, as well as reliability scores for each variable in brackets. A significant positive correlation was found between loneliness and restraint (r = 0.290**, p < 0.001), eating concern (r = 0.181**, p < 0.001), shape concern (r = 0.298**, p < 0.001), weight concern (r = 0.382**, p < 0.001), and global score (r = 0.324**, p <0 .001), which supports the hypotheses H1a-H1e.

3.3. The Effect of Gender on Loneliness and Disordered Eating Behaviors

Independent samples t-tests were conducted to examine the gender differences for loneliness, restraint, eating concern, shape concern, weight concern, and global disordered eating behaviors. A t-test was carried out to determine whether there is a significant difference between the means of the two groups, helping to assess whether observed differences are due to chance or a true effect.

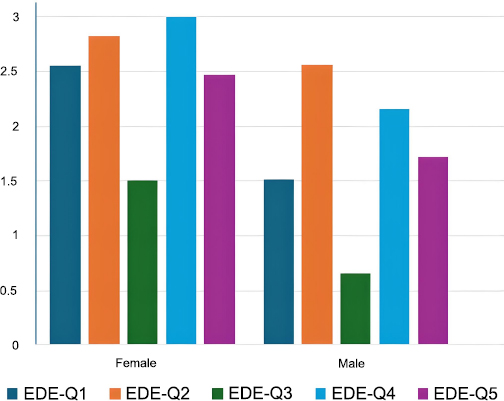

No statistically significant difference in loneliness scores was found between genders (t (378) = 1.922, p > 0.05). With 95% confidence, the true difference between the groups was found between -0.04568 and 4.03259. Additionally, there was no significant difference in eating concern scores based on gender, with differences in means ranging from -0.49769 to 1.04721. However, females exhibited significantly higher restraint (t (378) = 5.483, p < 0.001, difference in means ranging from 0.66394 to 1.40627), shape concern (t (378) = 5.572, p < 0.001, difference in means ranging from 0.54945 to 1.14864), weight concern (t (378) = 5.479, p < 0.001, difference in means ranging from 0.53051 to 1.12440), and global scores (t (378) = 4.217, p < 0.001, difference in means ranging from 0.39845 to 1.09474) compared to males. The mean differences in EDE-Q subscale scores are represented in Fig. (1).

Concerning correlations between variables in each gender, loneliness exhibited significant positive correlations with all EDE-Q subscales and the global score among females. Higher levels of loneliness were associated with greater restraint (r = 0.297, p < 0.001), eating concern (r = 0.219, p < 0.001), shape concern (r = 0.348, p < 0.001), weight concern (r = 0.345, p <0.001), and overall disordered eating behaviors (global score; r =0.341, p < 0.001). Significant positive correlations were also found among all the EDE-Q subscales and global scores among the female samples (p < 0.001).

| Variables | Mean | s.d. | UCLA | EDE-Q1 | EDE-Q2 | EDE-Q3 | EDE-Q4 | EDE-Q5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCLA | 2.4025 | 9.79 | (0.76) | - | - | - | - | - |

| EDE-Q1 | 2.17 | 1.84 | 0.290** | (0.94) | - | - | - | - |

| EDE-Q2 | 2.73 | 3.7 | 0.181** | 0.415** | (0.74) | - | - | - |

| EDE-Q13 | 1.19 | 1.49 | 0.298** | 0.678** | 0.437** | (0.74) | - | - |

| EDE-Q4 | 2.69 | 1.48 | 0.382** | 0.735** | 0.371** | 0.658** | (0.93) | - |

| EDE-Q5 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 0.324** | 0.801** | 0.829** | 0.780** | 0.759** | (0.89) |

**p <0.01.

Mean scores of EDE-Q 6.0 and subscales by gender.

Among males, loneliness exhibited significant positive correlations with weight concern (r = 0.421, p < 0.001), restraint (r = 0.228, p < 0.01), and global score (0.242, p < 0.01). However, it showed a non-significant positive correlation with eating concern (r = 0.092, p > 0.05) and shape concern (r = 0.120, p > 0.05).

The present findings revealed significant positive interrelationships among variables related to disordered eating behaviors, with females demonstrating stronger relationships than males.

3.4. The Effect of Relationship Status on Loneliness and Disordered Eating Behaviors

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to measure mean differences between UCLA scores and EDE-Q global scores among individuals who are single, in a relationship, and divorced or separated. ANOVA is used to compare the means of three or more groups to determine possible statistically significant differences among them while controlling for variance within groups.

Before conducting the one-way ANOVA, assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variance, and independence were checked. Normality was assured by the Shapiro-Wilk test, showing that residuals were normally distributed (p = 0.145). To check for homogeneity of variances, Levene's test indicated that the variances of groups did not significantly differ (p = 0.572). Independence was ensured in this research because of the design of the study. Since all assumptions were met, a one-way ANOVA was performed to compare loneliness scores in each relationship status group.

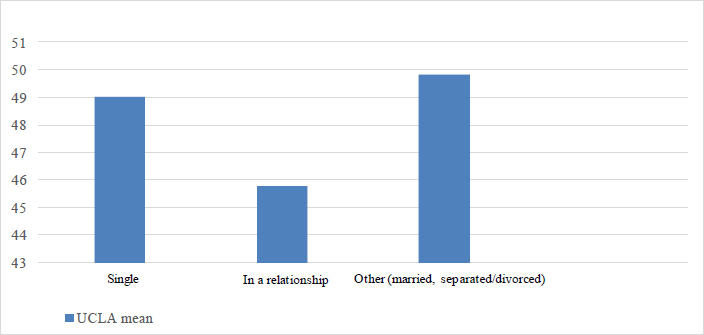

The ANOVA results demonstrated a statistically significant difference in loneliness scores between different relationship status groups (F (2,381) = 4.528, p = 0.011, η2 = 0.0232). With the application of Tukey’s HSD, the mean difference in loneliness scores between individuals who are single and those who are in a relationship was

Mean scores of UCLA by relationship status.

3.2, with a standard error of 1.1. This difference was statistically significant at the 0.05 level and p = 0.009. The 95% confidence interval for the difference ranged from 0.67 to 5.76, suggesting that individuals in a relationship tend to report significantly lower loneliness scores compared to those who are single. The mean scores of loneliness for each relationship status group are demonstrated in Fig. (2). No significant difference was observed in the EDE-Q global scores (F (2,381) = 0.892, p = 0.411, η 2 = 0.0047) after the execution of one-way ANOVA, checking for the corresponding assumptions.

3.5. The Influence of Gender and Relationship Status on Loneliness and Disordered Eating Behaviors: A Two-way ANOVA Analysis

A two-way ANOVA was performed to study the effects of gender and relationship status on loneliness. In general, a two-way ANOVA is used to examine the independent and interactive effects of two categorical independent variables on a continuous dependent variable while accounting for variance within groups. Prior to conducting the two-way ANOVA, the normality, homogeneity of variance, and independence assumptions were tested. Normality was tested through the Shapiro-Wilk test, and it revealed that the residuals were normally distributed (p = 0.157). Homogeneity of variance was assessed through Levene's test, and there were no significant differences in variance between groups (p = 0.286). The independence of observations was ensured in the study design. A two-way ANOVA was conducted due to the structure of our data. Specifically, the two-way ANOVA was used to examine the interaction between two independent variables (gender and relationship status) and their effect on the dependent variable (loneliness and disordered eating behavior). Unlike the simpler models, such as one-way ANOVA, two-way ANOVA allows the assessment of not only the main effect of each factor but also their interaction. This is particularly important in the study since it is assumed that the impact of one factor might be contingent upon the level of the other factor. Other models, including multiple regression, were considered, but with the categorical nature of the independent variables and the necessity of testing for interactions, the two-way ANOVA was the best option.

The full model was found to be significant: F (6, 377) = 2.434, p = 0.025, η2 = 0.037, clearly indicating that the two independent variables explain 3.7% of the variance in loneliness. The main effect of gender was not significant: F (2, 377) = 0.933, p = 0.394, η2 = 0.005; hence, differences between levels of loneliness by gender were not detected. There was a main effect of relationship status on loneliness: F (2, 377) = 4.479, p = 0.012, η2 = 0.023, although the effect is small. Furthermore, the interaction did not hold between gender and relationship status: F (2, 377) = 0.124, p = 0.884, η2 = 0.001; in that sense, the effect of relationship status on loneliness would be similar for both genders. Hence, it can be inferred that while being a male or female has nothing to do with loneliness, relationship status has little significant impact. Post hoc tests could be beneficial to determine at which level the relationship status groups differ in terms of loneliness.

In addition, a two-way ANOVA was carried out to determine the effects of gender and relationship status on the global score of EDE-Q. The assumptions were tested prior to the conduction of the two-way ANOVA. Computation results showed that the overall model is significant, with an F-statistic (6,377) = 3.944, p = 0.001, and η2 = 0.059, indicating that the independent variables were able to account for the variance of 5.9 in the global score. When gender was considered, this effect was found to be significant overall, with F (2, 377) = 3.143, p = 0.044, and η2 = 0.016, thus indicating that global scores were contingent, albeit slightly, on gender. On the other hand, the main effect for relationship status was not significant, indicating that relationship status did not affect global scores, with F (2, 377) = 1.294, p = 0.275, and η2 = 0.007. The interaction of gender and relationship status was also found to be non-significant with F (2, 377) = 0.201, p = 0.818, and η2 = 0.001, indicating that the influence of gender on the global scores of EDE-Q did not depend on relationship status. This suggests that gender has a small but significant impact on the EDE-Q global scores, while relationship status has no such important impression.

3.6. Regression Analysis

To assess the distinctiveness of each variable’s prediction of the outcome, regression was used in concordance with previous literature [23]. Multiple regression assumes linearity, independence of errors, homoscedasticity, normality of residuals, no multicollinearity, and no outliers. After checking each assumption, Table 2 demonstrates each dependent variable’s contribution to the independent variable by analyzing the coefficients, p-values (Sig.), and beta values. Weight concern holds the highest impact on loneliness (β = 2.228, p = 0.000), suggesting that weight concern has a significant effect on loneliness; shape concern demonstrates a weaker influence (β = 0.526, p = p >0.05), followed by restraint (β = -1.31, p > 0.05) and eating concern (β = 0.084, p > 0.05), suggesting a minimal and insignificant effect on loneliness.

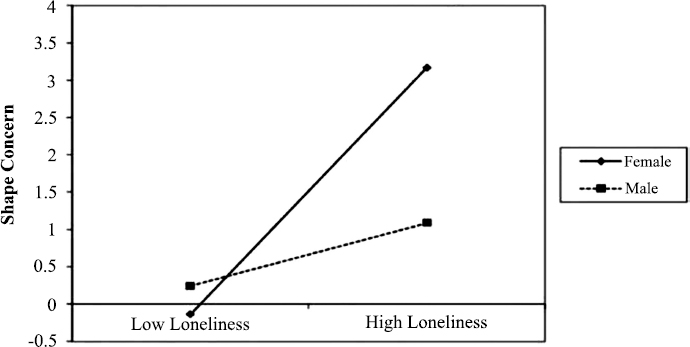

A regression analysis was conducted to check the moderation effect of gender on the relationship between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors. As shown in Table 3a, the effect of gender is not significant across any of the variables, with the smallest p-value being 0.085 for shape concern. The interaction between loneliness and gender is only significant for shape concern (p = 0.005), while the interactions for the other variables are not statistically significant (p-values > 0.05). As a result, Hypothesis 2 was rejected, with an exception to shape concern.

Table 3b demonstrates the interaction with relationship status as a moderating variable. As presented, loneliness has a marginal effect on restraint and a significant effect on weight concerns. Relationship status and interaction terms are generally not significant across measures, with only the effect of loneliness on weight concern showing clear significance. Hypothesis 3 was rejected.

3.7. Moderating Effect

As the interaction between loneliness and gender is significant for shape concern solely, as described in Table 3a, Fig. (3) illustrates the moderating effect of gender on the relationship between loneliness and shape concern using the method described in previous literature [23].

| - | β | Std. Error | t | Sig. | 95.0% CI for B | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UCLA | 41.418 | 1.000 | 41.501 | 0.000 | 39.516 | 43.446 |

| EDE-Q1 | -1.31 | 0.406 | -0.322 | 0.748 | -0.929 | 0.667 |

| EDE-Q2 | 0.084 | 0.142 | 0.592 | 0.554 | -0.195 | 0.363 |

| EDE-Q3 | 0.526 | 0.458 | 1.148 | 0.252 | -0.375 | 1.426 |

| EDE-Q4 | 2.228 | 0.489 | 4.560 | 0.000 | 1.267 | 3.189 |

| UCLA | Effect of Loneliness | Effect of Gender | Interaction between Loneliness*Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDE-Q1 | 0.07 (p=0.007) | -0.516 (p=0.858) | -0.015 (p=0.387) |

| EDE-Q2 | 0.144 (p=0.009) | 2.466 (p=0.186) | -0.057 (p=0.137) |

| EDE-Q3 | 0.096 (p=0.000) | 1.204 (p=0.085) | -0.041 (p=0.005) |

| EDE-Q4 | 0.048 (p=0.016) | -0.929 (p=0.17) | 0.004 (p=0.773) |

| EDE-Q5 | 0.09 (p=0.000) | 0.646 (p=0.425) | -0.027 (p=0.101) |

| UCLA | Effect of Loneliness | Effect of Relationship Status | Interaction between Loneliness*Relationship Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| EDE-Q1 | 0.049 (p=0.062) | -0.25 (p=0.784) | 0.003 (p=0.856) |

| EDE-Q2 | 0.004 (p=0.948) | -2.422 (p=0.199) | 0.049 (p=0.208) |

| EDE-Q3 | 0.015 (p=0.493) | -1.116 (p=0.085) | 0.023 (p=0.126) |

| EDE-Q4 | 0.062 (p=0.002) | 0.063 (p=0.93) | -0.004 (p=0.771) |

| EDE-Q5 | 0.032 (p=0.179) | -0.941 (p=0.261) | 0.018 (p=0.301) |

Interaction of loneliness and gender on shape concern.

4. DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to assess the relationship between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors among Lebanese young adults while comparing gender differences. The findings revealed significant positive correlations between loneliness and all the subscales of the EDE-Q, including restraint, eating concern, shape concern, weight concern, and the global score. These results are consistent with previous research demonstrating that loneliness is a significant factor associated with disordered eating behaviors [7, 14-17].

No significant difference in loneliness scores was found between female and male Lebanese young adults. This is presented in previous literature, although various studies suggest otherwise [3-6]. The difference in gender-related results could be due to cultural differences. As a result of the various conflicts that Lebanon has faced, it carries a wide history of emigration. The separation of many families around the world can lead to increased feelings of loneliness [24]. The Lebanese abroad have reported a sense of exile, increasing their feelings of loneliness and isolation [24]. Moreover, their relatives that remain in Lebanon not only face the crisis, but also grieve the separation of their families, making them more prone to feelings of loneliness. Underreported levels of loneliness due to the stigma around mental health in Lebanon could also affect the gender-related results, as the misconceptions have commonly led to the discouragement of individuals from seeking help [24, 25]. As for disordered eating behaviors, females showed significantly higher scores in all subscales of the EDE-Q, with the exception of eating concerns that were not significantly different among both genders, as also demonstrated in previous studies [8]. Specifically, restraint and other disordered eating behaviors were found to be significantly more common among females with body dissatisfaction [7]. The reported higher rates of disordered eating behaviors among females could be due to the underreporting of symptoms in males, as the stigmatization of mental health tends to be stronger for males in the Lebanese population [26]. When assessing gender as a moderating variable in the association between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors, the present study observed no moderating effect. The interaction between loneliness and gender was only found to be significant for shape concern. The reason for this could be cultural influences on body image. As societal expectations of beauty standards in Lebanon may focus on physical appearance, especially for women, this could increase the likelihood of disordered eating behaviors as a maladaptive coping mechanism for loneliness. This pattern has been previously represented in research, suggesting that cultural expectations may increase the risk of individuals engaging in disordered eating behaviors due to shape concern [27]. These pressures can increase concerns about body shape, possibly leading to destructive coping mechanisms. For males, the relationship between loneliness and shape concern may be moderated by gender-related stigma as the Lebanese society heavily stigmatizes mental health support for men. This may lead them to feel discouraged from openly expressing their emotions and asking for help. In this case, shape concern may be easier to report in comparison to other emotional vulnerabilities [28]. As a result, hypothesis 2 was rejected, with an exception to shape concern. Further research should be carried out to assess the distinction of this association among genders, as there is a lack of studies concerning this aspect in Lebanon.

Consistent with previous findings, a statistically significant difference in feelings of loneliness was observed among single individuals in comparison to those in a relationship, with individuals in a relationship reporting significantly lower scores of loneliness [9-12]. However, when assessing moderation, no significant effects were found between relationship status and the association between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors, thus rejecting hypothesis 3. The difference in feelings of loneliness may be explained by the emotional support and sense of belonging that intimate relationships provide [9]. Similarly, previous studies [10, 12] have reported that being in a relationship increases an individual's sense of relatedness through meaningful emotional connections. Although no significant difference was found between disordered eating behaviors and relationship status, the observed higher levels of loneliness among single individuals and its significant positive association with disordered eating behaviors suggests that single individuals may be more prone to disordered eating due to loneliness compared to those in a relationship. Further research could explore this association by considering both cultural and social factors with a direct study measuring loneliness and disordered eating behaviors, with relationship status as a moderating variable.

Concerning the direct association between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors, a significant positive correlation was found between loneliness and the EDE-Q subscales among Lebanese young adults, supporting hypothesis 1 (H1a-H1e). Consistent with past studies [7, 14-17], significant associations between loneliness and all EDE-Q subscales were also observed, with some gender-specific differences: females exhibited significantly higher levels of disordered eating behaviors across all EDE-Q subscales in relation to feelings of loneliness. In males, loneliness was significantly associated with restraint, weight concern, and the global score, but not with shape concern or eating concern. These findings suggest that individuals with higher levels of loneliness are more likely to engage in disordered eating behaviors. One plausible explanation for this could be that the emotional pain accompanied by loneliness may be heavy and overwhelming, increasing the tendency to use disordered eating behaviors as maladaptive coping mechanisms. In this case, individuals attempt to regulate their emotions through these behaviors. Notably, weight concern demonstrated the strongest association with loneliness, suggesting that feelings of isolation and social disconnectedness may be particularly related to preoccupations with body weight and associated behaviors.

5. LIMITATIONS

While the results of this study have a significant influence, several limitations are to be considered. Firstly, the cross-sectional design does not allow the supposition of causality between loneliness and eating disorders. Second, there is an insufficient number of studies measuring this association while putting into account the EDE-Q subscales, minimizing the support from previous research. In addition, a notable amount of previous research included several variables in their studies. However, the present study focused on loneliness and disordered eating behaviors while considering a few sociodemographic variables to allow for a more specific assessment of the association. Moreover, most of the participants in previous studies do not align with the present study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria, which could affect the discussion. Moreover, the UCLA Loneliness Scale and the EDE-Q have not been adapted to the Lebanese nationality. Furthermore, responses to the questionnaires, especially the EDE-Q, may have some inaccuracy, as a common characteristic of eating disorders is a lack of insight. Lastly, the results cannot be generalized to the entire Lebanese young adult population, as further studies must be conducted to assess the influence of possible confounding variables. As the study included only 384 participants as a sample size, this number may not be sufficient to generalize to the entire Lebanese young adult population. Furthermore, as a cross-sectional study, the results only provide an overview of the relationship between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors at a specific point in time and cannot establish causality or examine long-term associations.

CONCLUSION

The present study highlights the significant positive correlation between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors among Lebanese young adults for both genders (females and males), supporting hypothesis 1 (H1a-H1e). In addition, loneliness demonstrated several significant interrelationships with the EDE-Q subscales, with gender-specific differences. Although no significant gender differences were found in the association between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors, females reported more disordered eating behaviors in relation to loneliness across all the subscales of the EDE-Q, particularly across eating concern and shape concern. Additionally, relationship status was significantly associated with loneliness, with individuals who were single reporting higher levels of loneliness compared to those in a relationship. This could be due to the emotional connection and sense of belonging that accompanies meaningful relationships. Consequently, the association between loneliness and relationship status could suggest that individuals who are single and more prone to feelings of loneliness may have an increased risk of coping with disordered eating behaviors.

The findings indicate that gender has a small but significant effect on EDE-Q global scores, while relationship status influences loneliness but not eating disorder symptoms. Additionally, no significant interaction was found between gender and relationship status, suggesting their effects on loneliness and eating behaviors operate independently. In addition, there was no moderating effect of gender on the relationship between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors, except for shape concern, which presented to be higher for females. Also, there was no moderating effect of relationship status on the relationship between loneliness and the disorder eating effect.

While this study contributes to the understanding of the association between feelings of loneliness and disordered eating behaviors, several limitations exist. The cross-sectional design prevents causal inferences, self-reported scales may lead to response biases, cultural influences, and sample size may affect the generalizability of the findings to other populations.

Given the limited research directly addressing the relationship between loneliness and disordered eating behaviors, increased investigation into this topic can lead to more valid testing methodologies with further retesting. While the significance of this study extends globally, it holds particular importance in the context of the Middle East, as there is a lack of previous research on this subject, including Lebanon. Conducting this study among Lebanese young adults sheds light on the effect of loneliness on eating disorders in a previously overlooked and unique context. Exploring the connection between loneliness and eating disorders has the potential to shed light on interventions that could reduce their prevalence and identify more effective treatments. This contribution can hold significant importance to literature as it emphasizes the importance of taking into consideration loneliness when looking into eating disorders, and vice versa, while also increasing awareness, psychoeducation, and normalization. This can be considered and applied by several professionals through integrative treatment, such as mental health professionals, nutritionists, and health professionals. In addition, it can be implemented in prevention programs and interventions, especially in educational contexts. Intervention-based research could explore strategies to alleviate the effects of loneliness on disordered eating behaviors. Addressing loneliness in prevention and treatment efforts may be a crucial step in reducing the prevalence of disordered eating behaviors among young adults.

Longitudinal studies could be carried out to understand the direction and evolution of the association between feelings of loneliness and disordered eating behaviors over time whilst measuring the impact of psychosocial factors. Nevertheless, this study has assessed the relationship between two variables that were not found in previous research among Lebanese individuals, providing insight into an overlooked context. This study has found notable associations that are in concordance with previous research. The repetition of this study, especially as a longitudinal study, can lead to increased reliability and validity, potentially having significant impacts on today’s society, scientific research, and improved interventions.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: R.A.: Analysis and interpretation of results; N.S. and N.Z.: draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| EDE-Q | = Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire |

| ANOVA | = Analysis of Variance |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The Higher Center of Research (HCR) of The Holy Spirit University of Kaslik, Lebanon approved the protocol of this study and certified that this research had met the ethical criteria. The reference number is HCR/EC 2023-051.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committees and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The participants were provided with a consent form detailing the study's objectives, confidentiality measures, privacy assurances regarding their information, and their rights within the study, including the option to withdraw consent and participation at any point.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article is available in the Zenodo Repository at https://zenodo.org/records/15421389, reference number 10.5281/zenodo.15421389.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Elie Rahmé for his assistance in the methodological context of the study.