All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Can Parenting Styles Affect the Children’s Development of Narcissism? A Systematic Review

Abstract

The aim of this paper is to define whether different types of parenting styles (and which ones) affect the child's development in the direction of narcissism, through a systematic review of the studies on the subject in the literature, considering only research published from the Nineties to today. The ten studies considered in this review are representative of the main approaches used to investigate the association between parenting and the emergence of narcissistic features in children. These studies have used different research methods, operationalizing the concept of parenting in diversified ways and showing sensitivity to the multidimensionality of the construct of narcissism. The results of these studies allow us to say that types of positive parenting are more associated in general with the development of healthy narcissistic tendencies, compatible with the normal physical, mental and adaptive child's development.

INTRODUCTION

Narcissism can be defined as the capacity of each person to maintain a relatively positive self-image through a series of internal processes, and it fulfills the individual’s need for confirmation, success and self-enhancement in a social context [1, 2]. Narcissism as a psychological construct was introduced by Havelock Ellis (1898), who theorized the auto-erotic nature of man. It was developed later in psychoanalytic theory [3] and subsequently elaborated in theories of object relations and self-psychology [4, 5] and by other authors, thus becoming a fundamental node in the development of psychological thought. In the literature there is considerable disagreement about a univocal definition of this construct and researchers have fought keenly to impose their own definition and to define the specific traits of this phenomenon, concluding that its primary characteristic lies in its being a multidimensional construct, on a continuum spanning from healthy to pathological. Extremely high levels of narcissism are considered pathological, but narcissism in itself is seen as a normal personality trait [2, 6] that adopts a system of intra- and inter-personal strategies designed to maximize and protect self-esteem.

Despite the growing interest shown in recent decades towards the construct of narcissism, very little is known about its origins and the reasons for its development. Research into its origins could be vital to help us to understand the phenomenon better and therefore be able to design preventive interventions, thus promoting individual well-being [7-9]. Which psychological and environmental factors contribute to the emergence and maintenance of narcissism? What processes explain how one can deviate from a normal development of the Self? There are very few empirical studies about its origins. One study on personality disorders in identical twins suggests the presence of a genetic component in pathological narcissism [10], but recent research has focused on environmental factors that can contribute to the development of narcissism, especially on parental behavior or parenting [11].

Parental behavior or style refers to the parenting style in which parents generally relate to their children [12]. This style orients the construction of the relationship with the children and influences their psychophysical development: in fact, there are dysfunctional parenting patterns connected to the emergence of the main psychopathological phenomena in children. There is considerable disagreement about which kind of parenting is associated with the emergence of narcissism. In the literature, in fact, there are various conflicting clinical theories, the results of which do not converge on a single solution: a possible reason for this lack of convergence may lie in the fact that the researchers operationalized the concept of parenting in different ways and used different methodological approaches and instruments to measure constructs that are in fact very similar to each other. Although the literature contains numerous theoretical perspectives that are divergent in describing the nature of the etiology of narcissism, almost all the approaches somehow imply that a causal role is played by parental behavior [13-15]. There is no agreement on the style of parenting that is actually associated with narcissism.

The aim of this paper is to examine the empirical contributions that study this association, and, by reviewing these empirical studies systematically, to gain a better understanding of the parenting styles most correlated with the emergence of narcissism. This review has the intent of summing up in a narrative manner the findings of the main studies conducted since the 1990s, analyzing the documentation present in the literature, and considering the quantitative research articles that can give empirical confirmation to the real influence of parenting on the emergence of narcissism.

METHODS

Study Selection Criteria

The review included quantitative studies written in English, published in a peer-reviewed journal in the period from 1990-2014 (Table 1) which states that there may be a link between parental styles (operationalized in parental styles or dimensions) and narcissism (operationalized so as to be measurable using standardized measurement instruments).

The articles excluded, on the other hand, were those not supported by a recognized theoretical model, studies conducted outside the period taken into consideration in this review, studies not published in English, qualitative studies and those lacking a complete text.

| Characteristics of the study | Criteria of eligibility | Criteria of exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Type of studies | Empirical studies, quantitative studies, longitudinal studies, retrospective studies |

Qualitative studies, studies of single clinical cases |

| Year of article publication | Between 1990 and 2014 | Prior to 1990 |

| Language of publication | English | Other |

| Measurement instruments | Standardized | Non standardized |

| Studies’ theoretical model | Scientifically recognized | Not scientifically recognized |

Search Strategy

The research strategy consists of a review of the articles published in the period between 1990 and 2014, namely from the first attempts to study the association in question up to the most recent studies. The literature search was carried out by the author of this review in the electronic databases of studies Scopus, Medline, Proquest and The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) using the specific keywords: Narcissism and parenting style, Narcissism and parenting dimension and Child narcissism and parenting.

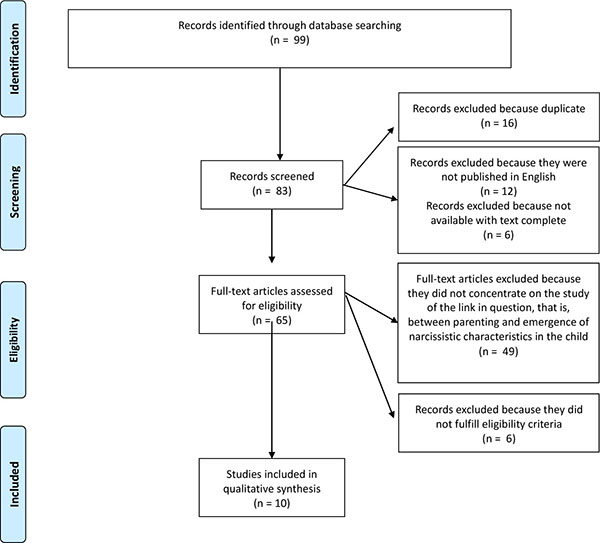

Initially, 99 articles were identified. Of these, 12 articles were immediately excluded because they were not published in English; 16 duplicates were removed and six articles were excluded because their full-text version was not available.

The remaining articles (N = 65) were then screened by examining their titles and abstracts, with the exclusion of those that did not concentrate on the study of the link in question, that is, between parenting (operationalized in a variety of ways) and the emergence of narcissistic characteristics in children (N = 49). Subsequently, six articles who did not fulfill the above criteria of eligibility were eliminated from the remaining articles. Finally, 10 studies were included in the review (see Fig. 1).

RESULTS

The 10 studies (Table 2) considered in the present investigation exemplify the main tendencies that have emerged since the 1990s in the empirical enquiry into the link between parenting and narcissism. The results of the studies included in the review are presented below in chronological order in order to highlight the direction being taken by the approach to this issue.

| Study | Participants | Instruments | Aim of Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) Narcissism and Parenting Styles – [17] | The participants were 324 university students (125 men and 199 women) enrolled in the first year of psychology. | Administration in sequence of a series questionnaires: Goal Instability and Superiority Scale [19], the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) [20], the Parental Authority Questionnaire (PAQ) [24] and lastly the Depression and Anxiety Scales [21]. | The parental styles of Baumrind are analysed using Kohut’s theory, in order to test three hypotheses empirically. The first states that the perception of the parents as authoritative is linked to less narcissistic immaturity; the second states that the permissive style is correlated to the onset of grandiose immaturity in the child and the third hypothesis states that the authoritarian parental style correlates with an inadequate process of idealization. The statistical analysis of the data obtained aimed to confirm the initial hypothesis. |

| 2) Self- Reported Narcissism and Perceived Parental Permissiveness and Authoritarianism – [22] | The sample consisted of 370 volunteer university students (151 males and 219 females). | The students were administered the Rosenberg [23] Self-Esteem Scale, the Parental Authority Questionnaire for mothers and for fathers (PAQ) [24], the Combined Parenting Style Index (CSPI) based on a scale created by Dornbusch et al. [25] and the O’Brien [26] Multiphasic Narcissism Inventory (OMNI). | The aim of the study was to use the data from the administration of the questionnaires to empirically verify the hypothesis that an inadequate parenting style (permissive or authoritarian) favors the development of pathological narcissism. |

| 3) Narcissism and Childhood Recollections: A Quantitative Test of Psychoanalytic Predictions – [27] | The participants were 60 men and 59 women average age 28.8 years (range = 18-52). | To measure overt narcissism the 40-item version of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) [36] was used. The presence of covert narcissism was measured using the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS) [37]. To measure childhood memories of parental indifference, coldness, rejection, trust and overestimation, a 15-item scale was developed deriving from consideration of the psychoanalytic theories on the origins of narcissism [3, 13-15]. | The aim of this study is to understand whether narcissism is associated with cold, indifferent, rejecting parental styles [14, 15]with excessive praise and admiration [13] or with some combination of the two types of parenting [3], by studying this association in a non-clinical sample, and to see whether different childhood experiences can be associated with different forms of narcissism. |

| 4.1) Parenting Narcissus: What are the Links Between Parenting and Narcissism?– [28] Study n.1 |

The participants were 222 psychology students (139 females and 62 males). | The participants were administered the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) [6], the Children’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI) [38, 39], and lastly Rosemberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) [23]. | The aim of the study is to empirically test the three theoretical hypotheses found in the literature: 1. According to Millon and according to Kohut’s idea of parental indulgence, narcissistic children will report that their parents are loving, involved and not strict (what Baumrind calls permissive parental style) [12]. 2. Kohut states that narcissism derives from over-involved parents that fail to contribute to creating an autonomous self in the child; therefore, parents that are described as psychologically controlling and also involved with their children should have children with higher tendencies to narcissism. 3. Kernberg’s theoretical perspective suggests that narcissistic children have cold, strict, controlling parents. This combination of parental dimensions has been called “authoritarian” [12]. |

| 4.2) Parenting Narcissus: What are the Links Between Parenting and Narcissism? – [28] Study n.2 |

The participants in this study were 214 high school students 87 males and 127 females. | The participants completed the NPI, a measurement scale assessing parenting, the psychological control scale, the RSE and various other assessments. | The aim of this study is the same as in the previous study (Study 1). |

| 5) The Predictive Utility of Narcissism among Children and Adolescents: Evidence for a Distinction between Adaptive and Maladaptive Narcissism – [29]) | The participants were 98 children aged between 9 and 15. 47% of the subjects were female. | The participants completed the Narcissistic Personality Inventory-Children (NPIC) [40] and the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire (APQ) [41]. |

The aim of the research is to empirically test the hypotheses that healthy, adaptive narcissism is correlated with positive parenting practices and that on the other hand maladaptive or pathological narcissism is associated with negative parenting practices. |

| 6) Comparing Clinical and Social-Personality Conceptualization of Narcissism - [30] | The participants in this study were 271 university students, 56% of the subjects were female. | The participants were assessed using various measurement instruments, the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire, (PDQ-4+) [42], the Narcissistic Personality Inventory [36], the Psychological Control Scale (PCS) [38] and the Parenting Warmth and Monitoring Scale [43]. | This study used an empirical approach to try to clarify the confusion existing about the various concepts of narcissism, specifically between the concept used in the clinical setting and the one most common in the social-personological literature. Among the various hypotheses tested here, the one of interest for our review states that narcissism is strongly linked to memories of negative parenting (for instance parental coldness). |

| 7) Self-Functioning and Perceived Parenting: Relations of Parental Empathy and Love Inconsistency With Narcissism, Depression and Self-Esteem – [31]. |

The participants were 373 first-year psychology students at university. | The participants completed the Interpersonal Reactivity Index [44] the Love Inconsistency Scale for mothers and for fathers [45], the Self-Esteem Scale [23], the Narcissistic Personality Inventory [20] and lastly the Depression Scale [21]. | This study investigates the way explicit operationalizations of the parental empathy or parental inconsistency received, correlate with the major measurements of narcissistic development. |

| 8) Young Adult Narcissism: A 20 year longitudinal study of the contribution of parenting styles, preschool precursor of narcissism and denial – [32] | The 102 participants in this study came from the Longitudinal Project. These individuals were recruited at the age of three years and the sample was assessed at different ages starting from 3 years (1968) until the age of 23 (1988). | The instruments used were the California Child Q-set (CCQ) [46] and the California Adult Q-sort (CAQ) [47] and lastly the Defence Mechanism Manual [48]. | The aim of this study is to demonstrate that adaptive (healthy) narcissism and maladaptive (pathological) narcissism found at the age of 23 may depend on the early presence of precursors of narcissism and on the kind of parental style that the child experiences. |

| 9) Adolescent Grandiose and Vulnerable Narcissism: Associations with Perceived Parental Practices – [33] | The participants were 300 teenagers (257 males and 43 females). | The material presented to the participants was the Alabama Parenting Questionnarie (APQ) [41] and the Pathological Narcissism Inventory (PNI) [2]. | The aim of this study is to examine the relation between teenagers and parents’ reports on parental pratices and the manifestation of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in the teenager. |

| 10) Clarifyng the Links between Grandiose Narcissism and Parenting – [34] | 98 males and 47 females, all students, participated in the study. | The instruments used was the Narcissistic Personality Inventory to assess grandiose narcissism, a 6-item scale to assess monitoring [43], 15 items measuring parental support [43] elsewhere called warmth [28] and, lastly, 11 items to measure parental coldness and 4 items to measure overestimation, developed by Otway and Vignoles [21]. | The aim of the study is to investigate the association between parenting and grandiose and vulnerable narcissism, with the hope of clarifying the recent empirical discrepancies resulting from different studies conducted on the issue. |

The researchers Watson, Little and Biderman [17], in a study on a sample of 324 university students, analyzed the correlation between parental styles as theorized by Baumrind [18] and the emergence of narcissism in children, according to the theoretical perspective presented by Kohut [15]. The data show that authoritative parenting is somehow incompatible with the grandiose immaturity of the Self typical of narcissism, demonstrated by the negative correlation of this style with Goal Instability [19], a scale based on Kohut’s theory that measures the tendency to immaturity in the development of idealization and grandiosity, and with the Exploitativeness subscale of the Narcissism Personality Inventory [20] which represents the pathological and maladjusted aspects of narcissism. The first hypothesis tested is therefore confirmed: narcissistic immaturity correlates with an inadequately authoritative parenting style. Therefore, a deficit in the development of the Self is associated with a lack of optimal parenting, positive parental behavior that can shape the child’s psychological development by means of optimal frustrations. The benefits of an authoritative style are also shown by the negative correlation with depression measured by the Depression and Anxiety Scales [21]. It is also shown that a permissive parental style is a significant predictor of grandiose narcissistic immaturity while authoritarian style, as hypothesized, is shown to be associated with a deficit in the development of processes of idealization of others, depression and goal instability.

In 1996 the researchers Ramsey, Watson, Biderman and Reeves [22] administered to a sample of 370 university students a booklet of questionnaires containing the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale [23], the Parental Authority Questionnaire for mothers and fathers (PAQ) [24], the Combined Parenting Style Index (CSPI) based on a scale created by Dornbusch, Ritter, Leiderman, Roberts and Fraleigh [25] and the O’Brien Multiphasic Narcissism Inventory [26] (OMNI). The data recovered support the hypothesis that an inadequate parenting style favors the development of pathological narcissism. The scores from the OMNI, in fact, correlate with the measurements obtained by the PAQ of permissive maternal and paternal parental styles and with measurements of authoritarian maternal and paternal styles. On the other hand, no link is shown to exist between the OMNI and the measurements of authoritativeness in parental style. Self-referential narcissistic tendencies in the OMNI correlate directly with the parents’ perception of having an authoritarian or permissive parental style.

Otway and Vignoles [27] try to use their empirical investigation to overcome the discrepancy existing in the literature about the etiological cause of narcissism: both cold, indifferent and rejecting parental styles [14, 15], and overestimation with excessive praise and admiration [13], as well as some combination of the two types of parenting [3] are said to lead to narcissism. It is also hypothesized that the first type of parenting is associated with covert narcissism and the second with overt narcissism. Following the statistical processing of the data collected from the questionnaires administered to 119 participants, the researchers did not find a straightforward correspondence between parental overestimation and overt narcissism, and between parental coldness and covert narcissism, but the results suggest that the combination of parental overestimation/admiration [13] and coldness [14, 15] is the key factor in predicting both kinds of narcissism, overt and covert. Nevertheless, a slight difference was found: memories of parental overestimation are slightly more predictive of covert narcissism.

Horton, Bleau and Drwecki [28] investigated the relation between parental dimensions (i.e., warmth, monitoring and psychological control) and narcissism in two studies in which the participants – 222 university students in the first and 212 high school students in the second – were administered the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, self-esteem measurement scales and standard measurements of the three parental dimensions. The results of Study n.1 show that parental warmth is the only dimension that is a predictor of healthy narcissism. However, both parental warmth and psychological control reported by the participants in their accounts of perceived parental styles proved to be predictive of pathological narcissism. Study n.1 presents a variety of methodological challenges which reduce the likelihood of drawing definite conclusions exclusively from these data. One of the criticisms moved to the present study refers to the fact that the participants were not living with their parents when the questionnaires were administered, which would make their reports on their parents more prone to errors of memory. Study n.2 makes up for this flaw by using a sample of high school students living with their parents at the time of their testing. The results of this study suggest that warmth is positively associated to healthy narcissism, just like psychological control, which is also positively linked to it but not in a significant way.

By contrast, the dimension of monitoring is negatively associated to scores of healthy narcissism. The data processing shows that the interaction between monitoring and psychological control is significant: reports of psychological control are positively associated with narcissism when there are high levels of monitoring, and negatively when the levels of monitoring are low. As was shown in Study n.1, also in the present study warmth is positively and significantly predictive of pathological narcissism. Both the dimensions of psychological control and monitoring are predictive of pathological narcissism: high levels of psychological control and low levels of monitoring, tend to produce higher participants’ scores for pathological narcissism.

In a study carried out in 2007 by the researchers Barry, Frick, Adler and Grafeman [29] on a sample of 98 children the hypotheses tested were that adaptive narcissism correlates positively to positive parenting practices (i.e., positive reinforcement, parental involvement), while maladaptive or pathological narcissism is associated with negative parental practices (i.e., little or no monitoring and supervision, strict discipline). The results show that the scores from the measurements of positive parenting correlate positively with the adaptive subscales in the Narcissism Personality Inventory-Child (NPIC), while negative parenting correlates with the NPIC subscales (Entitlement, Exploitativeness, Exhibitionism) that measure the maladaptive or pathological aspects of narcissism, and not healthy narcissism.

Miller and Campbell [30] conducted a study in 2008 on a sample of 271 university students, in order to clarify the confusion existing about the conceptualization of narcissism. Among the various hypotheses presented in this study, the one that is of interest for our review stated that narcissism would be significantly related to memories of negative parenting such as parental coldness. After assessing the three main dimensions of parenting (warmth, monitoring and psychological control), the researchers evaluated the association of each one with narcissism. The data collected using the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) shows that there is a negative association between monitoring and adaptive narcissism in both male and female participants, while the data from the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire (PDQ-4+) suggest that psychological control has a positive correlation with pathological narcissism.

In the study conducted in 2008 by Trumpeter, Watson, O’ Leary and Weathington [31], the authors examined the relation between parental empathy, love inconsistency and measurements of narcissism, self-esteem and depression in a sample of 232 university students. The data confirm the hypotheses that the parental empathy received correlates positively and significantly with levels of self-esteem and with adaptive forms of narcissism, and negatively with pathological narcissism and depression. Moreover, the perception of love inconsistency correlates negatively with self-esteem and forms of healthy narcissism, and positively with pathological narcissism and depression.

In the longitudinal study conducted by Cramer [32], the participants were assessed at age three for the presence of precursors of narcissism, and parents provided information about their parenting style. At the age of 23, the presence of healthy or pathological narcissism was assessed, along with the use of defense mechanisms. The data suggest that authoritative and permissive parental styles are positive predictors of healthy narcissism, while the authoritarian style is a negative predictor of this kind of narcissism. It is shown that the mother’s marked use of a nonresponsive parenting style, and also of an authoritarian style, combined with a precocious tendency to narcissism, increases the possibility of developing pathological narcissism in adulthood. Similarly, the weak use of responsive parenting styles (i.e., permissive, authoritative) by mothers, combined with a precocious tendency towards narcissism, increases the likelihood of developing pathological narcissism. When the mother has high scores in authoritative and permissive styles, the presence of narcissistic precursors at age three does not act as a predictor of pathological narcissism, while for lower scores such precursors are significant predictors of pathological narcissism at the age of 23 years. As far as the father’s parenting style is concerned, the only statistically significantly association found is the positive correlation between an authoritative style and healthy narcissism.

The researchers Mechanic and Barry [33] conducted a study on 300 teenagers, with the aim of examining the link between the accounts of parenting practices given both by the teenagers and by the parents themselves, and forms of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism in teenagers. The results obtained suggest that, as hypothesized, grandiose narcissism has a positive and significant relation with parental involvement and with the use of positive reinforcement, while vulnerable narcissism is predicted significantly only by an inconsistent use of discipline. The hypothesis presented in the study, stating that high levels of grandiose narcissism are predicted by an interaction between high positive reinforcement and weak monitoring and supervision, was not confirmed, nor was the fourth hypothesis that stated the existence of an interaction between the use of positive reinforcement and high inconsistent discipline in predicting higher levels of vulnerable narcissism. No relation was found between the teenagers’ accounts of parental practices and the accounts given by the parents.

Horton and Tritch [34] studied the association between parenting styles and grandiose narcissism, in order to shed light on the recent empirical discrepancies. They used the Narcissistic Personality Inventory to assess grandiose narcissism. The authors of the study created a single general score to evaluate the level of grandiose narcissism by counting the “narcissistic” answers given by the subjects in the questionnaire, and the composite scores on four NPI subscales: Leadership, Self-Absorption, Superiority and Entitlement. Considering the total NPI score, high scores on coldness should be associated with low scores on the measurement of narcissism, while high scores in psychological control should be associated with high levels of grandiose narcissism. The monitoring, support, and overestimation dimensions would not be associated with the overall NPI score. When the composite scores of four NPI subscales are considered, psychological control correlates positively and significantly with the subscales of Entitlement and Superiority. Parental coldness correlates negatively with the Superiority and Leadership subscales, the monitoring dimension is negatively associated to the Entitlement subscale, while the parental dimensions of overestimation and support are not predictive of any subscale, and there is no parental dimension that is significantly associated to the Self-Absorption subscale.

DISCUSSION

By reviewing the 10 most significant studies on the issue, this paper aimed to clarify which type of parenting actually affects the development of narcissism and which does not. The study of the origins of narcissism began to receive a great deal of empirical attention in the Nineties, and it has often been influenced by the theories found in the literature on the role that parenting might play in the development of various forms of narcissism. Although the clinical perspectives differ in their description both of the nature and of the etiology of narcissism, almost all of them in some way involve the role of parental behavior. One of the reasons for the lack of convergence in the results is the fact that researchers have measured parenting styles using different methods of assessment for constructs that are conceptually similar. There are three dominant but contrasting hypotheses in the literature: according to Millon and according to Kohut’s idea of parental indulgence, pathological narcissism is produced by loving, warm, involved parents who are not strict, that is, who show behaviors corresponding to the parental style that Baumrind [18] calls “permissive” (Hypothesis 1). Kohut states that narcissism derives from over-involved parents who fail to contribute to creating an autonomous self in their child; therefore, parents described as psychologically controlling, and who are also marked by parental involvement, are more likely to have children with greater tendencies towards narcissism (Hypothesis 2). Kernberg’s theoretical perspective suggests (Hypothesis 3) that narcissistic children have cold, strict, controlling parents, a combination of aspects labelled “authoritarian” by Baumrind. The pioneers in studying the association examined in our review are the researchers Watson, Little and Biderman [17] who operationalized parenting into the parental styles as theorized by Baumrind. According to this authors, the hypothesis that the parental styles most predictive of narcissism are the authoritarian and permissive styles is confirmed: this would therefore support Kohut’s theory that the types of parenting unable to produce optimal frustration (the former being too frustrating, and the latter not frustrating enough) seem to be associated with higher scores on the NPI. Ramsey, Watson, Little and Biderman [22] obtained the same results in their study, demonstrating that narcissistic tendencies self-reported in the OMNI correlate directly with the perception of authoritarian or permissive parents, confirming once more the theoretical hypothesis found in Kohut’s theory which states that inadequate parenting contributes to a narcissistic pathology. In his study, Cramer [32], also operationalizes parenting in terms of parental styles, but to test the association between the latter and narcissism he uses a longitudinal study that also considers the child’s initial tendency to narcissism as well as the kind of parental style and an assessment of the level of narcissism twenty years after the initial assessment: in this case the data suggest that it is only the authoritarian style that predicts narcissism in adulthood above all in the presence of precursors at the age of three, while authoritative and permissive styles are not predictive of narcissistic tendencies, even when there were precursors at an early age. The outcome of this research shows that adaptive narcissism can be predicted by early gratification of physical and psychological needs through the implementation of “responsive” parenting (i.e., with high levels of warmth) attentive to the child’s needs, and not by unresponsive and more “demanding” behaviors (i.e., with high levels of control).

Additional contradictory results were obtained in the study conducted by Otway and Vignoles [27], the outcome of which suggests that both cold and controlling parental styles [14, 15], and an excess of praise and overestimation [13] are predictive of both kinds of narcissism, overt and covert.

In the two studies conducted by Horton, Bleau and Drwecki [28], the analysis is not confined to parental styles, but extends to the dimensions of parenting (i.e., warmth, monitoring and psychological control) and the effects that the combination of various dimensions in interaction may have on the development of healthy narcissism (which is associated with positive traits of self-esteem) and pathological narcissism. The results suggest that warmth is positively associated with both kinds of narcissism, and that monitoring has a negative association with healthy/adaptive narcissism. Therefore, permissive parenting would appear to be linked to healthy narcissism, a result which is consistent with the theories of both Kohut and Millon. At the same time, the reports of parents that are involved but permissive are linked in Study n.2 to pathological narcissism. The key to understanding the way permissive parental style is related to both the forms of narcissism may lie in psychological control, the only dimension that predicts pathological narcissism and not healthy narcissism. The results of the last two studies are in sharp contradiction: presuming that parental warmth and coldness are negatively correlated to each other, these two measurements would be expected to predict narcissism in opposite ways, while, based on the data collected, both warmth [28] and coldness in parenting [27] serve as predictors of narcissistic tendencies.

Similar results to those obtained by Otway and Vignoles [27] can be found in the study conducted by Miller and Campbell [30]. In said study, the researchers also operationalized parenting in terms of dimensions, and the data collected again show the existence of a negative association between monitoring and adaptive narcissism, and a positive association between psychological control and pathological narcissism.

In their 2007 study, researchers Barry, Frick, Adler and Graefman [29] showed that negative parental practices (i.e., scarce monitoring and supervision, consistent discipline) reported both by parents and children, correlate positively with forms of pathological narcissism, while positive parental practices correlate with the adaptive subscales of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory-Children.

Similarly, Trumpeter, Watson, O’Leary and Weathington [31] showed that parenting characterized by empathy correlates with adaptive narcissism, while the presence of love inconsistency and, therefore, of aspects of negative parenting are associated with pathological narcissism. As in previous studies [17, 22], there is a confirmation of Kohut’s theory [15] that the development of healthy narcissism occurs thanks to the presence of empathic and “optimally frustrating” parents. The two most recent studies included in our review are the only ones that consider the grandiose and vulnerable dimensions of narcissism in investigating their possible association with parenting.

Mechanic and Barry [33] revealed a correlation between positive parental practices and grandiose narcissism, while the vulnerable form is associated with negative parenting (i.e., inconsistent discipline). This association is not surprising since grandiose narcissism is marked by an “inflated” self-perception and the desire to dominate regardless of personal abilities or achievements [2]. It is therefore possible that an excessive use of positive parental practices might create a sense of superiority, and grandiose fantasies of adoration and perfection: this would seem consistent with Millon’s theory [13]. Moreover, coherently with the results of previous studies [31, 32], confirming some aspects of the theories of Kohut and Kernberg [14, 15] the inconsistent discipline measured in the study under exam, which would represent the same parental aspects operationalized in different ways in other studies (e.g., lack of empathy and warmth, non-responsive parents, love inconsistency), correlates positively with the vulnerable form of narcissism.

The results of the study conducted by Horton and Tritch [34] would lead us to believe that the dimension of psychological control is the only predictor of grandiose narcissism, in view of the total score obtained on the NPI. If, on the other hand, the association with the NPI subscales is considered, the dimensions of overestimation and support do not correlate with any of the subscales. Psychological control correlates positively with narcissistic tendencies measured in the Entitlement and Superiority subscales, while parental coldness correlates negatively with narcissism. This is the opposite result of that presented in the study by Otway and Vignoles [27].

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, this study attempted to ascertain the correlation existing between parenting and narcissism. However, in the light of the above results it must be concluded that further research needs to be done on this issue since the results obtained do not provide statistically certain answers. On top of the contradictory outcomes reported by numerous studies, there are the methodological challenges that such empirical enquiries present. First of all, it must be highlighted that most of this research is based on perceived and self-assessed parenting experiences, which were based on retrospective memories. Since narcissists are inclined to distort information so as to make it better suited to their own self-aggrandizement, it is possible that their accounts are systematically subject to bias [35]. To compensate in part for this possible error, most of these studies do not take into consideration parents’ self-report of their parenting behavior, so as to assess more accurately the truthfulness of the children’s perception of the parenting received.

The results of these studies allow us to understand that, in general, positive parenting is more associated to the healthy development of narcissistic tendencies. However, the contradictions and the sometimes conflicting results prevent us from stating with certainty which specific dimensions of parenting actually cause narcissism.

There are numerous questions that research has not yet been able to answer: it is possible that the direction of the influence is the opposite of that hypothesized, since it could be the child’s innate narcissism that produces a certain style of parenting in the adult [22], just as it is impossible to rule out the presence of other variables that are interposed between the two constructs investigated, which could prevent us from establishing a correlation with certainty.

In spite of the numerous results obtained, there is no “unifying systematicity” in the approach, in the method and in the operationalization of the constructs [35]. There is a lack of studies that investigate the way the various parental dimensions found to be associated with different forms of narcissism are related to each other: future research should, for instance, explore how authoritarian and permissive styles can be linked to the perception of cold and overestimating parents in predicting narcissistic behaviors. From this review it emerges that there are still numerous limitations and methodological challenges to be faced in studying the correlation between parenting and narcissism, and, despite the efforts of many researchers, a great deal of work remains to be done in order to reach any definite conclusions [28].

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author confirms that this article content has no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Patrizia Perotti for collecting and coding the data.