All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Using an Embodiment Technique in Psychological Experiments with Virtual Reality: A Scoping Review of the Embodiment Configurations and their Scientific Purpose

Abstract

Background:

In recent years, psychological studies with virtual reality have increasingly involved some eEmbodiment tTechnique (ET) in which the users’ bodily movements are mapped on the movements of a digital body. However, this domain is very fragmented across disciplines and plagued by terminological ambiguity.

Objective:

This paper provides a scoping review of the psychological studies deploying some ET in VR.

Methods:

A total of 742 papers were retrieved from Scopus and the ACM Digital library using “embodiment” and “virtual reality” as keywords; after screening them, 79 were eventually retained. From each study, the following information was extracted: (a) the content of the virtual scenario, (b) the extent of the embodiment, and (c) the scientific purpose and measure of the psychological experience of embodiment. This information is summarized and discussed, as well as reported in tabular format for each study.

Results:

We first distinguished ET from other types of digital embodiment. Then we summarized the ET solutions in terms of the completeness of the digital body assigned to the user and of whether the digital body's appearance resembled the users' real one. Finally, we report the purpose and the means of measuring the users’sense of embodiment.

Conclusion:

This review maps the variety of embodiment configurations and the scientific purpose they serve. It offers a background against which other studies planning to use this technique can position their own solution and highlight some underrepresented lines of research that are worth exploring.

1. INTRODUCTION

The first attempts to integrate a user's body into a graphical and interactive digital object date back to the early Nineties [1-4]. In 1994, Slater and Usoh described the situation in which the “proprioceptive signals about the disposition and behavior of the human body and its parts become overlaid with consistent sensory data about the (. . .) “Virtual Body”” [3]. Studies using some Embodiment Techniques (ET) have then accumulated.

The term embodiment is used loosely with reference to various technical solutions, very different from those referred to by Slater and Usoh in the quotation above. For example, sometimes, the term embodiment refers to the bodily appearance of a virtual agent [5, 6], such as the virtual agents helping to use some software and endowed with a character-like digital body, such as the animated paper clip in Microsoft Office [7]. Robots are also often described as having an embodiment, with reference, in this case, to their physical appearance and the way it allows them to interact with their surroundings [8]. Even when the term embodiment refers to a digital body assigned to the user, it might merely consist of a digital representation that gives users a visible appearance [1, 2, 9]. The purpose of these representations is to strengthen the social presence of the user interacting with other users in a digital environment or to facilitate remote collaboration by conveying information such as the users’ location, state of activity, attention focus, or availability [9, 10]. These representations are not coupled with the user’s real movements.

The kind of embodiment referred to by Slater and Usoh requires interactivity, namely that the digital body moves based on the users’ movements. As a result, the user will feel to control the virtual body, own it, and be present in it (sense of embodiment, SE), [12–15]. Interactivity, in which the users can act upon virtual objects [15], and receive timely feedback from those actions [16-18], is the factor making a digital world appear as real [19]. In the specific case of a digital body, interactivity makes it feel so real that the participant’s body boundaries and configuration will be altered. This experiential alteration is confirmed by neuropsychological evidence; for instance, maneuvering a stick in a virtual environment results in including that stick in the user’s peri-personal space, cognitively coded in the same way as the user’s natural body [20]. The same phenomenon enables therapeutic applications of ET, e.g., correcting a distorted body image [21].

Given the ambiguity of the way in which the term “embodiment” has been used and the distribution of ET studies across disciplines, our objective is to compose a scoping review of state of the art in VR psychological experiments that use some kind of ET. While a systematic review answers a research question, a scoping review covers the literature in a certain domain to summarize and disseminate its research findings [22]. In this review, Embodiment Techniques (ET) identifies those technical solutions that couple the users' movements with a digital body's movement by using advanced tracking systems. Sense of Embodiment (SE) instead, is “the ensemble of sensations that arise in conjunction with being inside, having, and controlling a body especially in relation to virtual reality applications” [11]. The existing reviews on ET focus on the sense of presence [23], self-reported measures of embodiment in an avatar [24, 25], or the definition of embodiment [11]. The findings we want to summarize here are the technical configuration of the ET in VR and the scientific purpose they served. Having this information will allow new studies to position more clearly their methodology within the current options and make their results easier to compare with the existing ones.

2. METHODS

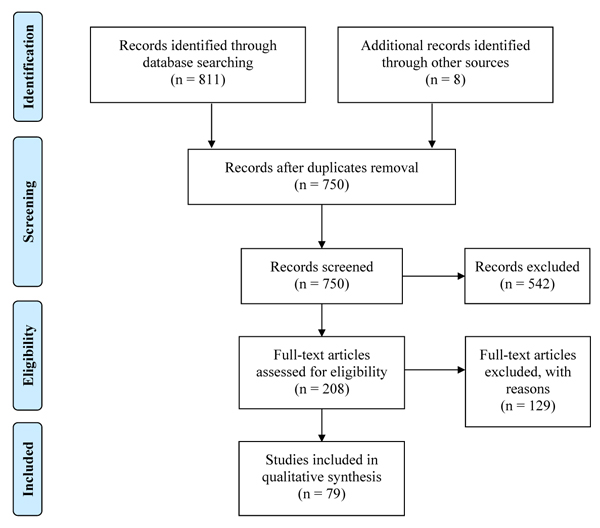

To collect the set of papers for this review, we used Scopus and the ACM Digital library as databases. The former is Elsevier’s comprehensive database of peer-reviewed scientific papers that also includes conference proceedings; the latter covers all peer-reviewed works published in the journals and conferences sponsored by ACM and IEEE, the two largest international scientific associations for scholars of computers and interaction with computers. We performed our queries using “embodiment” and “virtual reality” as keywords in February 2019. The search returned 811 records; 8 more records were added because experts recommended them. After removing the duplicates, 750 papers remained. We then screened all the records to select the studies that focused on the users’ experience of embodiment. We, therefore, excluded studies that by “embodiment” referred to the mere virtual representation of a person or character; or referred to the appearance of an artificial agent; or did not include tracking some users’ body parts; or described some technological solutions without analyzing the users’ experience of embodiment. On their titles and abstracts, we performed the first screening for relevance, further reducing the sample to 208 papers; a second screening was performed on the full text of these papers, leading to a sample of 79 publications, all in English (Fig. 1).

We then extracted information from each publication according to a template that fitted the purpose of our study. We extracted descriptive information about the research settings and methods to reflect the state of the art of the ET domain, consistently with the purpose of a scoping review [22]. Since we did not re-code the findings or extract information according to coding schemes that required a subjective judgment, we did not resort to independent coders. The information extracted was the sample composition, the content of the virtual environment, the devices adopted to track the users’ body, the level of embodiment, the purpose with which ET was used, and the measures of the psychological experience of being embodied in a digital object. This punctual information is reported as Annex 1. In the rest of this paper, we will summarize the information extracted; we will describe the content of the virtual scenarios (section 3.1.2), the extent of the digital embodiment (section 3.1.1), the scientific purpose of ET (sections 3.2.1) and measure of the psychological experience of embodiment (section 3.2.2). We will conclude by pointing out which lines of investigation are underdeveloped.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Technical Solutions

3.1.1. Embodiment Level

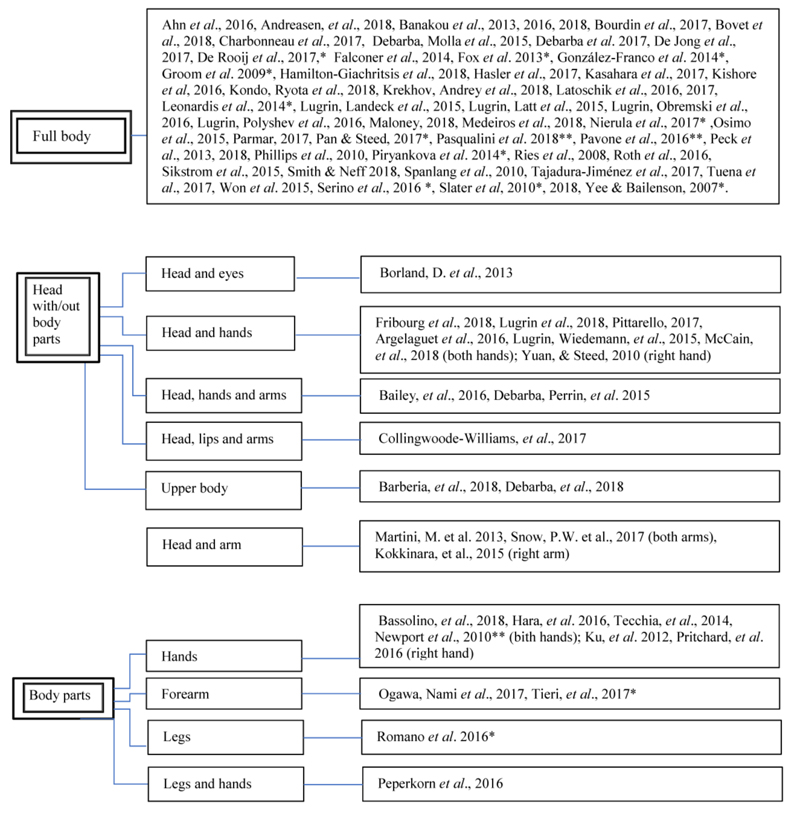

The studies reviewed here vary in the completeness of the digital body assigned to the user, as summarized in Fig. (2). The digital environment can assign a complete body to the user (full body) or just some bodily parts. Of the 79 studies analyzed here, 57 provided the user with an entire virtual body (72.2%). In the other cases, only the body parts of relevance to the goal of the study were represented, e.g., hands and arms [25], hands and feet [26], hands and torso [27], or some substituted/modified parts of the body [28, 29]. The choice depends on the object of the study, which makes it relevant that only some parts of the digital body interact with the surrounding environment or are visible. For instance, Ku et al. [25] investigated the brain activation during a simple action in the virtual environment offering the participant a first-person perception of their virtual body. The action, in this case, was a handshake and, therefore, the embodiment only consisted of a visible digital forearm and hand. In the case of Kondo and colleagues [26], the very purpose of the study was to limit the completeness of the digital embodiment to test if it was effective; they investigated whether showing only the digital hands and feet in the VE could be sufficient to make participants believe that they owned the virtual body.

The mapping of the users’ bodily movements into the movements of the digital body was obtained in most cases via tracking devices. However, not all studies tracked the users’ entire body, even when the digital body was displayed in the virtual environment was a complete body. Indeed, there was no correspondence between the extent of the digital body and the extent to which the study equipment tracked the user's real body. When there was no need to differentiate the movements of the different parts of the body, the digital body could be obtained by simply tracking the user's orientation (studies marked by one asterisk in Fig. (2)) via a Head-Mounted Display (HMD) (92.4%). De Jong and colleagues [30], for example, investigated whether touch affected the body ownership illusion (BOI); thus, they organized the digital and real environment so that the participant could simultaneously receive a virtual and digital stroking gesture, to check whether the sense of ownership of the virtual body was affected. This experimental paradigm did not require tracking the participants' body movements inside the VE.

Instead, when there was a need to separately control the movements of different parts of the digital body, then additional tracking devices were used. For example, Argelaguet et al. [31] studied how the visual realism of the hand representation affected the sense of embodiment in VR. They reproduced the participants' hands with three different levels of visual realism (abstract vs. iconic vs. realistic) but kept the same controls, based on a tracking system using Leap motion. Only the most realistic visual representation would accurately map the degrees of freedom of the real and virtual hand. In this study, it was then necessary that the fine movements of the real hand were tracked. The users’ hands and arms are tracked via wireless controllers [27, 32-34], touchless devices such as Leap Motion [31, 35, 36] or optical, infrared cameras paired with active markers (LED sensors) or passive markers (retro-reflective trackers) [29, 37-39]. In one paper, even the lip movement was tracked with a microphone-based tool, Lipsync [40]. In some studies (48.1%), all major body parts were tracked, making it possible to control the different parts of the digital body with the user’s real body movements. Hamilton-Giachritsis et al. [41], for instance, investigated the mothers' perspective-taking and empathy with children. The mothers participating in the study were digitally embodied in a virtual 4-year-old child and interacted with a virtual mother having a relaxed or angry attitude. In this study, the whole body of the mothers was tracked and synchronized with the virtual body. In most cases, the body was tracked by pairing an infrared-cameras system with several markers positioned on the participant via tight-fitting suits (68.4%; of the 38 studies with a full-body tracking); other motion-sensing devices were the Kinect, a marker-free motion capture system [26, 42-47], and, more recently, camera-free motion tracking devices, such as Vive [48, 49], which offered a full-embodiment set-up at a relatively low budget.

3.1.2. Digital Content

All studies but four [42, 43, 47, 50] allowed users to experience their virtual body (or body parts) from a first-person perspective. The digital body's appearance either resembled or modified the users' real one, depending on the research goal. The users' gender was swapped to test stereotypical threat [51]; its age was modified to study object size-estimation [52, 53], compassionate responses [54], maternal perspective-taking, and empathy [41]; the skin color was manipulated to study racial prejudice [49, 55-58], and pain threshold [29]; the appearance was sexualized to study women’s body objectification [59]; and body weight and body dimension were modified to study one's body representation [60], the body-ownership illusion [30, 61], object size-estimation [36] and perceived pain [62].

Digital embodiments that did not display any gender, age, or race feature have also been used; mannequin-like avatars appeared in a study on social interactions [63], silver and undetailed avatars were used in a study on spatial cognition [39], and alien-like avatars were used in a study investigating the near-death experience [64]. Participants had been given the virtual appearance of famous people such as Albert Einstein [65], Sigmund Freud [66], Lenin [34], or Kim Kardashian [33], to study the effect on the performance of taking somebody else's perspective. Some studies investigated body-ownership using animal-like avatars such as bats [48, 67], tigers and spiders [48], cows and corals [68], fictional creatures like Godzilla [69], and angels [70].

The virtual environment also can either reproduce the user's real environment or be different from it. In the former case, the embodied user would sit at a table in a room similar to the real lab [36, 51, 61, 71-77]. In the latter case, the research goal and the experimental task would require users to inhabit a virtual environment that is very different from the physical one: outdoor environments, such as terrains with trees [70], virtual oceans [68], or alien islands [64]; indoor environments such as flats [78], hallways [79], rooms with furniture [80, 81], or libraries [26]; urban landscapes [12, 45, 69], and environments from past time in history [34, 35].

3.2. Psychological Effects of the Embodiment Technique

3.2.1. Purpose of Applying the ET Technique

We included in this review only the studies that, in addition to using an ET, were interested in the psychological effects of being embodied in a digital object. The specific purpose of ET in each study in this review is listed in the Annex. We will summarize these purposes here by distinguishing between studies in which the sense of embodiment was the primary concern and those in which it was instrumental to studying other psychological phenomena.

Among the studies focused on the psychological experience of embodiment, some aimed at finding an effective technical apparatus able to generate a sense of embodiment. They would study the effectiveness of a specific technical setup [32, 72, 90] or compare the effectiveness of different technical setups [71, 91, 92]. Some technical options differed in terms of their psychological properties, i.e., the sensory/perceptual/motor feedback [12, 26, 50, 75, 90, 91], the field of view [37], the perspective on the virtual body [13, 46], the level of pictorial realism [31, 92], or the agency [67]. Some studies tested the effectiveness of embodiments that were highly different from the real users’ body in terms of functioning or appearance [48, 62, 93-100]. Finally, among the studies focused on the psychological experience of embodiment, some were interested in exploring its neurological correlates [26, 73, 101].

Of the studies using embodiment techniques to affect some other psychological processes, some were using ET to boost the effectiveness of the digital experience, such as enjoyment [34, 35] or performance (task performance, e.g., completion time [96, 97], limb movement during rehabilitation [69], fitness performance [92], cognitive tasks [65], game performance [27], and embodied cognition [98]). This improvement would be engendered by simply endowing the user with a digital embodiment, or, in other cases, by endowing them with a digital body whose attributes differed from the users’ real ones, i.e., a fitter body [42].

Psychological effects were also investigated by modifying specific aspects of the embodiment. The digital embodiments changed the users’ social identity and, in turn, their perception of discriminated social categories [49, 56-59], children [41], nature [69], the architectonic environment [99], or of themselves (self-compassion [54],). The new identity could affect the performance in a specific task, such as finding new solutions [66], having creative ideas [80], overcoming fear responses [100] or stereotypes threats [51]; and it could change the users’ preferences (e.g., narcissistic choices [33], self-confidence and self-disclosure [101], self-objectification [59]). Specific manipulations of the digital embodiment affected body perception (rubber hand illusion [102]), the estimation of body width and circumference [60] or weight [103] and even some bodily states (hand temperature [77]). It affected spatial perception, such as the estimation of the size of objects [36, 38, 52], distance perception [79], space-valance association [39], or accuracy in judging egocentric distances [104]. And it affected the response to stimuli, such as pain [62, 76, 81, 105], threat [28] or phobic stimuli [74].

3.2.2. Measures of the Sense of Embodiment

While the ET consists of using a specific technical setup, the sense of embodiment (SE) refers to the psychological effect resulting from using this technique to interact with the virtual environment. The SE combines three feelings: self-location, a sense of agency over the virtual body, and body ownership [11-14].

- By self-location, the literature refers to the “spatial experience of being inside a body” and is different from the sense of being located within the virtual environment as a whole (spatial presence [11, 14]. Self-location is captured by using behavioral indices such as affordance estimation and body size estimation [61], proprioceptive judgments of space and body [38] and self-report questionnaires [11, 13, 91].

- The sense of agency is the sense of having motor and action control of the body driven by intention and will [31, 37, 51, 53, 56, 67, 90, 106]. Agency is believed to require congruence between the expected movement and the movement perceived by the senses (visuomotor correlation) [11, 14]. Firstly explored by Peck and colleagues with a six-item scale [57], questionnaires measuring agency have also included measures of the perception of the self-reflection generated by a virtual mirror and of the body as it is seen by looking down at oneself [40, 41, 52, 55, 64-66]. Subdimensions of the agency include movement, enjoyment of body control, movement control, and movement cause [43]. Agency, in turn, can be a subcomponent of the illusion of virtual body ownership [47].

- The sense of body ownership is the self-attribution of a body (virtual or physical), deriving from sensory information (e.g., visual, tactile, or proprioceptive). It is believed to derive from synchronizing the real with the virtual body [11, 107] and was initially studied in association with the rubber hand illusion with a questionnaire [108]. That questionnaire was then adapted to fit settings with a full virtual body [32, 75, 77]. Ad hoc scales [86] or mixed-method questionnaires with open and closed-ended questions [42, 109] have also been used. Besides questionnaires, body ownership has also been measured with physiological indices [12, 28, 74, 78, 109] electroencephalogram, and electromyography [72].

4. DISCUSSION

In this paper, we collected and offered an overview of the existing solutions to display, capture and measure the users' embodiment in virtual reality to improve the recognizability and focus of a concept that has often been used loosely. To conclude, we will describe the areas in which future efforts can be devoted.

First, less than half studies (48.1%) provided users with full-body tracking. Many of the studies only used an HMD to adapt the digital body to the position of the user’s body. Since full-body tracking is becoming more common and affordable, it should be increasingly considered in studies investigating social interactions or spatial perception.

Second, only a few studies ventured to consider the interaction between embodied users; this remains an unexplored terrain open to future investigation [32, 63, 110]. This could be improved in combination with the usage of virtual environments where two embodied users are co-present and interact. The virtual environments adopted in ET studies are mostly designed to be visited by one user at a time; the studies foreseeing multiple users connected at a distance [1, 2, 111] or located in the same physical environment [32, 59, 63, 101, 110] are infrequent.

Third, we included in this review only the studies that, in addition to using an ET, were interested in investigating the psychological effects of being embodied in a digital object. But many other studies explore some technical solutions that are assumed to induce SE but are not tested with users. We encourage the use of measurements listed in this review to validate the designers’ claims.

CONCLUSION

Finally, it might be worth emphasizing that although embodiment helps to achieve a sense of presence [3, 25, 79] or empathy [112], it is not a necessary condition to them. Sense of presence and empathy can be achieved by interacting with the VE via non-embodied input modalities without having the body graphically represented in the VR [113, 114]. Therefore, including an ET in the technical setup of ones’ study should be motivated by exploiting within the narrative the interactive possibilities of the virtual body.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| VR | =Virtual Reality |

| VE | =Virtual Environment |

| HMD | =Head-Mounted Display |

| ET | =Embodiment Technique |

| SE | =Sense of Embodiment |

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARDS OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines were followed in this study.

FUNDING

This study was supported by a grant from Ministero dell'istruzione, dell'università e della ricerca (Dipartimenti di Eccellenza DM 11/05/2017 n. 262) to the Department of General Psychology of the University of Padova, and by the University of Padova via a doctoral fellowship.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.