All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Structural Equation Model (SEM) of Matrilineal Parenting, Family and Community Environments on Adolescent Behavior in Padang City, Indonesia

Abstract

Introduction:

This research aims to explain the effect of family and community environment on the causal relationship between matrilineal parenting and adolescent behavior.

Methods:

This research employs a survey with a cross-sectional design. The population was mothers with adolescent children living in Padang City, Indonesia. The survey was distributed using Google Form, and the data were analyzed using Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM).

Results:

The analysis revealed five findings as follows: (1) family environment has a significant positive influence on adolescent behavior; (2) family environment has a positive influence on matrilineal parenting; (3) community environment does not have an influence on adolescent behavior; (4) community environment does not have an influence on matrilineal parenting; and (5) matrilineal parenting has a positive influence on adolescent behavior.

Conclusion:

Matrilineal parenting and the family environment greatly influence the behavior of adolescents. There are three matrilineal parenting components that provide guidance and direction to adolescents, namely mothers, fathers, and Mamak (uncle). When the matrilineal parenting style and family environment are good, adolescents have a strong personality that is not easily influenced by other factors.

1. INTRODUCTION

Adolescent age is often described as a period, which is full of spirit, involves the development of abilities and independence, but also is at risk of antisocial behavior and mental problems [1-3]. For example, adolescents are likely to get involved in various crimes of robbery, murder, and drug trafficking that affect their physical and psychological health in the future [4-6]. Thus, adolescents must have a strong personality that may not be disrupted by various negative factors [7]. The development of personality cannot be separated from a set of behavior owned by individuals. According to Kapetanovic and Skoog [8], behavior is defined as the potential and skills that individuals should inculcate to make their life good in a society or community. In other words, an individual can achieve a better life when they are capable of acquiring positive behavior that can also determine a strong personality. Individual behavior can be influenced by various factors. As is the case with adolescents, while the social environment such as school and peer groups greatly influence the behavior of adolescents [9-15], the interaction between family members can also be attributed to determine their personality development [16, 17]. This indicates that parents have a significant role in strengthening the positive behavior of adolescents.

Be Cheah [18] asserted that the mother's attention has a positive impact on the development of adolescents' strong personalities. Further, it is emphasized that adolescents with good behavior are pillars of future development. Being religious, honest, disciplined, independent, confident, creative, unyielding, polite, caring, cooperative, tolerant, and communicative are parts of good behavior. All of the behavior is manifested in suitable actions for themselves and others [19] consequently, it is very important to foster adolescents’ behavior through parents’ guidance and direction in the family [20, 21].

There are three factors that determine the behavior of adolescents, namely the environment in the family, parenting styles, and the community environment [8]. These factors contribute to the development of adolescents’ personalities [9]. The community environment is proven to be beneficial for adolescents; for example, they can contribute to better school performance; be assiduous, confident, and optimistic; and reduce adolescent selfishness [22-24]. A good family environment will provide a sense of security and comfort for adolescents. In addition to attention from parents, family atmosphere, interaction with the family members and socioeconomic status, support the development of adolescents' behavior [25-29]. Therefore, parenting style determines adolescents’ personalities. The parenting styles that have been implemented by parents, in general, are authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parenting. The implementation of each style has a different impact on the behavior of adolescents [30-34].

One of the recent research on the behavior of adolescents was conducted by Cheah [18], in which, he examined the influence of parenting and social identity on the development of Muslim American adolescents’ behavior. The research revealed that the mother's warmth moderates the relationship between religious socialization practices and the development of adolescents' positive behavior. Then, Lerner et al. [35] discussed the behavior that must be developed in adolescents, namely honest, humble, persevering, future-oriented, and goal-oriented. Moreover, Yan-Li et al. [26] carried out the research whose findings revealed that there is a close relationship between the family environment, parental care, parental readiness, and adolescent behavior. In addition, Wagner [36] investigated the role of the strength of personality in peer relationships among early adolescents in Switzerland. The result showed that honesty, humorousness, kindness, and fairness are expected the most by teenagers from a friend. Furthermore, Sáenz et al. [37] revealed that the role of family members in providing support for children's education is vital.

Despite a plethora of research reports on the influence of parenting on adolescents' behavior, similar research on the context of matrilineal care has not been widely discussed. Based on the aforementioned gap, this article discusses the behavior of adolescents in matrilineal parenting, particularly the Minangkabau matrilineal system in Indonesia. The Minangkabau matrilineal system is one of the biggest societies in the world [38]. Matrilineal care is collective care different from conventional care in the nuclear family [39]. In the Minangkabau matrilineal system, caring is not only the responsibility of the parents but also the Mamak (uncle) [40, 41]. Mamak is the most important individual to look after his sister's children [42]. All the above-mentioned are involved collectively to form children's expected personality [43].

In light of the importance of matrilineal parenting for adolescent behavior, this recent research aims to determine the effect of matrilineal parenting on adolescents’ personalities in the context of the Minangkabau matrilineal system [18, 44, 45]. Further, to address the aims, the researchers focused on the following research questions.

(1) How is the influence of the family environment on adolescent behavior?

(2) How is the influence of the family environment on matrilineal parenting?

(3) How is the influence of the community environment on adolescent behavior?

(4) How is the influence of the community environment on matrilineal parenting?

(5) How is the influence of matrilineal parenting on adolescent behavior?

2. METHODS

2.1. Sample

Utilizing a cross-sectional survey design [46], a total of 296 families were sampled using a multistage random sampling technique from a population of 11 districts in Padang City, West Sumatra, Indonesia. The age range of respondents was 15 years - < 64 years. In terms of age, 4 respondents (1.4%) were 20 years old, 24 respondents (8.1%) were 21 - 40 years old, 264 respondents (89.2%) were 41 - 60 years old, and 4 respondents (1.4%) were < 60 years old. In terms of educational background, 24 respondents (8.1%) were primary school graduates, 39 respondents (13.2%) were junior high school graduates, 96 respondents (32.4%) were senior high school graduates, 13 (4.4%) had a diploma, 90 respondents (30.4%) had a bachelor degree, 31 (10.5%) had a master degree, and 3 (1.0%) had a doctoral degree. Based on the occupations, 78 respondents (26.4%) were civil servants, 157 respondents (53.0%) were housewives, 21 respondents (7.1%) were self-employed, 40 respondents (13.5%) and 21 respondents (7.1%) were private employees. The distribution of respondents based on the number of children is as folloes: 218 respondents (74%) had 1-3 children, 73 respondents (25%) had 4-6 children, and 5 respondents (2%) had 7-9 children. Lastly, in terms of Mamak, 240 respondents (81%) had 1-3 Mamak, 52 respondents (18%) had 4-6 Mamak, and 4 respondents (1%) had 7-8 Mamak.

2.2. Instrument

This research employed a questionnaire comprising four variables: matrilineal care, adolescent behavior, family environment, and community environment. The questionnaire consisted of 147 items with a 5 point Likert scale design assessing the frequency of items, from 'always', 'often', 'sometimes', 'never', to 'never at all’ (Table 1).

| Variable | Indicator | Questionnaire Number |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Behavior | Religious | 1-6 |

| Honest | 7-8 | |

| Discipline | 9-13 | |

| Independent | 14-17 | |

| Confidence | 18-22 | |

| Creative | 23-26 | |

| Never give up | 27-28 | |

| Respect and courtesy | 29-33 | |

| Care | 34-35 | |

| Cooperation | 36-37 | |

| Tolerance | 38-41 | |

| Communicative | 42-44 | |

| Matrilineal Parenting | Authoritarian | 45-56 |

| Authoritative | 57-74 | |

| Permissive | 75-92 | |

| Family Environments | Parents attention | 93-96 |

| Relationships between family members | 97-108 | |

| Home atmosphere | 109-114 | |

| Socio-Economic Status | 115-118 | |

| Community Environments | Friends Associating | 119-127 |

| Environmental lifestyle | 128-134 | |

| Activities in the community. | 135-142 | |

| Mass media | 143-147 |

2.3. Procedure

The questionnaire was distributed to participants using a Google Form. Before the questionnaire was distributed, it was tried out on mothers not included in the actual research sample and validated by three professors and a lecturer colleague who were experts in fields related to research variables. The Government of West Sumatra Province, Indonesia, had given official written approval to carry out this research. In addition, participants in this research had given their consent before filling out the questionnaire voluntarily. Withdrawal of participation from the research was also allowed at any time. The data collection was carried out for twenty days.

2.4. Data Analysis

This research used a theoretical model analysis with Partial Least Square-Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) and was assisted by SmartPLS 3.0 version 3.2.7 software [47]. PLS-SEM is a variant-based technique that has been widely used in the increasingly popular tourism, business, and technology research [48]. However, the technique is rarely used to explain the behavior of adolescents and parenting in families. Structural equation modeling based on Variance PLS-SEM can be a suitable methodological alternative for testing covariance-based structural equation theory [49, 50].

This research refers to a general guideline for using PLS-SEM with a two-step technique, namely evaluating the Measurement Model (Outer Model) and designing the Structural Model (Inner Model). These two steps were conducted to analyze a theoretical research model [51, 52].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Measurement Model (Outer Model)

Evaluation of the feasibility of the measurement model and structural model has been carried out to ensure reliability and validity. Evaluation of the measurement (outer model) has been conducted to find out that each indicator in each variable has a good relationship with the other indicator. The outer model in Structural Equation Modeling-Partial Least Square (SEM-PLS) is evaluated through four stages, namely:

3.1.1. Convergent Validity

Convergent validity in SEM-PLS is also known as the loading factor . The level of convergent validity can be measured from the test results of loading factors. The indicator is valid if the value of loading factors is greater than 0.70. The results of the output loading factors are presented in Table 2.

| Adolescent Behavior | Family Environment | Community Environment | Matrilineal Parenting | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KR1 | 0.885 | |||

| KR10 | 0.854 | |||

| KR11 | 0.918 | |||

| KR12 | 0.916 | |||

| KR2 | 0.913 | |||

| KR3 | 0.831 | |||

| KR4 | 0.905 | |||

| KR5 | 0.914 | |||

| KR6 | 0.887 | |||

| KR7 | 0.940 | |||

| KR8 | 0.777 | |||

| KR9 | 0.935 | |||

| LK1 | 0.896 | |||

| LK2 | 0.918 | |||

| LK3 | 0.,952 | |||

| LK4 | 0.921 | |||

| LM1 | 0.966 | |||

| LM2 | 0.902 | |||

| LM3 | 0.963 | |||

| LM4 | 0.938 | |||

| PPM1 | 0.897 | |||

| PPM2 | 0.946 | |||

| PPM3 | 0.909 |

Table 3 shows that the results of this research indicator have sufficient convergent validity because all indicators have a loading factor value greater than 0.7, thus the indicators in this research were valid and this test was appropriate to be continued to the next stage.

| Forner-Larcker Criterion | Average Variance Extracted | Cronbach's Alpha | Composite Reliability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Behavior | Family Environment | Community Environment | Matrilineal Parenting | ||||

| Adolescent Behavior | 0.891 | 0.793 | 0.976 | 0.979 | |||

| Family Environment | -0.858 | 0.922 | 0.850 | 0.941 | 0.958 | ||

| Community Environment | -0.906 | 0.777 | 0.943 | 0.889 | 0.958 | 0.970 | |

| Matrilineal Parenting | 0.952 | -0.788 | -0.936 | 0.918 | 0.842 | 0.906 | 0.941 |

3.1.2. Discriminant Validity

Based on the results of discriminant validity testing through the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the square root of AVE (√) for each construct was greater than the correlation of each construct with other constructs, which was more than 0.70. Thus, it can be concluded that the constructs or variables in this research had a good discriminant validity. The results of the Fornell-Larcker criterion test are presented in Table 3

3.1.3. Average Variance Extracted (AVE)

Average Variance Extracted (AVE) is conducted to determine the validity of each construct value. For constructs with good validity, the AVE value must be above 0.50. Based on the results of the tests, all variables in this research had an AVE value of more than 0.50. Therefore, all latent variables in this research were good at representing indicators. The results of the AVE test are presented in Table 3.

3.1.4. Composite Reliability and Cronbach Alpha

The data processing using SmartPLS of each of the latent variables in this research showed that all variables had a Cronbach's alpha value and composite reliability of more than 0.70. Therefore, all latent variables in this research were reliable and the model built had a very good level of reliability. The results of the value of composite reliability and Cronbach alpha are presented in Table Based on the results of the outer model by testing convergent validity, discriminant validity, average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability, it can be concluded that the outer model in this research had fulfilled the requirements specified in the stages of Structural Equation Modeling-Partial Least Square (SEM-PLS) research. Therefore, this research was appropriate to be continued to the next stage.

3.2. Structural Model (Inner Model)

Structural Model (inner model) is built in four stages, namely by looking at the results of the values of R-Square, Multicollinearity, F-Square (F2), Q-Square (Q2), and Goodness-of-Fit (GoF). The description of the test results of each test component is as follows:

3.2.1. Results of R-Square

R-Square is used to determine how much the independent latent variable influences the dependent-latent variable in order to see the proportion of the dependent variable influenced by the independent variable. The R2 result of 0.67 indicates that the model is categorized as good, while the R2 result of 0.33 is categorized as moderate, and the R2 result of 0.19 is categorized as weak.

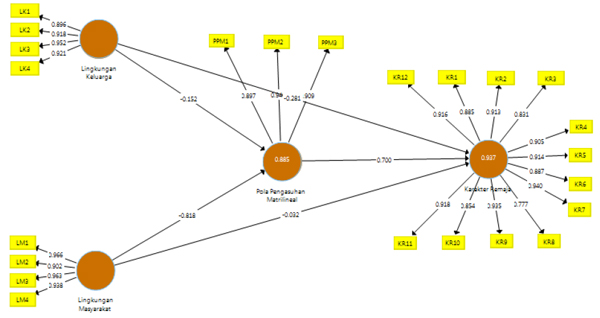

The results of SmartPLS 3.0 version 3.2.7 show that there were two values from the R-Square. The first R-Square obtained a value of 0.937 for the dependent variable of adolescent behavior with respect to the independent variables of matrilineal parenting, family environment, and community environment. The R-Square indicates that the independent variables of matrilineal parenting patterns, family environment, and community environment could explain the dependent variable of adolescent behavior by 93.7%, while the remaining 6.3% was influenced or explained by other variables that had not been included in this research model. The R2 result of 0.937 indicates that the variables in this research model had a good relationship.

The second R-Square obtained a value of 0.885 for the dependent variable, matrilineal parenting, with respect to the independent variables of family environment and community environment. The R-Square indicates that the variables of family environment and community environment could explain the dependent variable of matrilineal parenting by 88.5%, while the remaining 11.5% was influenced or explained by other variables that had not been included in this research model. The R2 result of 0.885 indicates that the variables in this research model had a good relationship.

3.2.2. Results of Multicollinearity

Multicollinearity is conducted to determine the correlation between constructs. Therefore, the relationship between one construct and another must be completely different. To find out whether multicollinearity existed between the constructs in SEM-PLS through SmartPLS 3.0 version 3.2.7, the results of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) value had been obtained. If the VIF value is > 5.0, it can be considered that there is multicollinearity.

The results of the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) test showed that the VIF value for each variable in the research was less than 5.0. Therefore, it has been concluded that the variables in this research were free from multicollinearity problems. In other words, the constructs built had different characteristics from other constructs so there was no need for construct changes. The results of the multicollinearity test are presented in Table 4.

| Adolescent Behavior | Matrilineal Parenting | |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescent Behavior | ||

| Family Environment | 2.728 | 2.527 |

| Community Environment | 4.351 | 2.527 |

| Matrilineal Parenting | 4.708 |

3.2.3. Results of F-Square

The results of the F-Square value test indicated that community environment variables had a weak influence on adolescent behavior because the result of the F-Square value test was 0.002. The variable of family environment had a medium influence on matrilineal parenting due to the F-Square value of 0.079. The variables of family environment and matrilineal parenting exhibited a strong influence because the F-Square values for each variable were 0.458 and 0.889, respectively.

The variable of community environment had a strong influence on matrilineal parenting due to the F-Square value of 2.304. Therefore, the variables of matrilineal parenting and family environment for adolescent behavior and the variables of family environment and community environment for matrilineal parenting were suitable to be used in this research. Meanwhile, the predictive variable of the community environment for adolescent behavior was found to be less suitable to be used in this research.

3.2.4.. Results of Q-Square

The results of the Q-Square in this research indicated Q-Square value to be 0.93. Thus, the research model exhibited a good predictive value because the value was greater than zero, namely 0.93. The result of the Q-Square test is as follows:

Q2 =1-(1-R12)(1-R22)

=1-(1-0.937)(1-0.885)

= 0.93

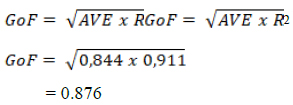

3.2.5.. Results of Goodness of Fit (GoF)

Based on the data obtained from the previous SmartPLS output, the average AVE value was 0.843, and the average value of R2 was 0.911. After obtaining the average AVE and R2 values, the next step was to calculate the Goodness of Fit value based on the formula below.

The GoF result was 0.876, which was greater than 0.38. Thus, it can be concluded that the model built had a good Goodness of Fit. After testing R-Square, Q-Square, and Goodness of Fit, the model formed has been considered as robust [25, 20]. The outer model and inner model outputs of the SEM-PLS model that had passed the testing stages and found to be robust are as follows:

Fig. (1) shows that hypothesis testing can be done by determining the t-statistic value and the probability value. To test the hypothesis in this research, a significance level of 5% was used so that the t-statistic value used was 1.96. The criteria for accepting a hypothesis are based on t-statistics; if the t-statistic > 1.96, then the hypothesis is accepted and vice versa. Furthermore, the criteria for rejecting or accepting the hypothesis are based on probability; if p-value < 0.05, Ha is accepted.

Based on the bootstrapping test in the SmartPLS software shown in Fig. (1), the t-statistic value for the variables of family environment and matrilineal parenting with respect to adolescent behavior and the variables of family and community environment with respect to matrilineal parenting had shown a value above 1.96. Meanwhile, the variable of community environment for adolescent behavior had exhibited a t-statistic value below 1.96. Hypothesis testing in this research used a one-tailed test, which indicates whether it has a positive or negative effect. The acceptance or rejection of the hypothesis can be seen from the bootstrapping report in the Path Coefficient presented in Table 5.

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | P Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Environment -> Adolescent Behavior | -0.281 | -0.285 | 0.029 | 9.581 | 0.000 |

| Family Environment -> Matrilineal Parenting | -0.152 | -0.154 | 0.026 | 5.842 | 0.000 |

| Community Environment -> Adolescent Behavior | -0.032 | -0.030 | 0.048 | 0.662 | 0.508 |

| Community Environment -> Matrilineal Parenting | -0.818 | -0.816 | 0.024 | 33.840 | 0.000 |

| Matrilineal Parenting -> Adolescent Behavior | 0.700 | 0.700 | 0.054 | 12.858 | 0.000 |

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. The Influence of Family Environment on Adolescent Behavior

The family environment is the first and major aspect that influences the behavior of adolescents. They spend more time in the family environment so family plays a significant role in developing their personality. The family greatly determines the good and bad behavior and the personality of adolescents [54]. Although, there are also other influential factors.

Based on the output path coefficients mentioned in Table 5, the variable of family environment had been shown to have a positive and significant influence on adolescent behavior. This was evidenced by the t-statistic value of 9.581, which was greater than 1.96, and the significance was recorded at alpha 5% (P-value < 0.05). Thus, the hypothesis accepted H1. In other words, the family environment had been found to exert a significant positive influence on adolescent behavior.

This result is in line with the findings in the research conducted by Krauss, Orth and Robins, which explains that various conditions in the family environment form the behavior of adolescents [52]. In addition, good communication and support provided by the family have a significantly positive influence on adolescent attitudes and behavior [55-57]. An unsupportive family environment for adolescents, such as a conflict between parents and violence in the family, initiates psychological disorders and affects the development of adolescent behavior [29, 58, 59]. Therefore, the family environment greatly determines the adolescent behavior.

4.2. The Influence of Family Environment on Matrilineal Parenting

The family environment also has an influence on parenting style in the family. The parenting style of families living in villages is different from those who live in cities [60, 61]. Likewise, the socioeconomic status of each family has an influence on parenting in the family [62-63].

Based on the output path coefficients listed in Table 5, the variable of family environment had been found to have a positive and significant influence on matrilineal parenting. This has been evidenced by the t-statistic value of 5.842, which was greater than 1.96, and the significance was set at alpha 5% (P-value < 0.05). Thus, the hypothesis accepted H1.

This research reveals that a good family environment formulates the patterns of parenting in the family [64-65]. Interaction and cooperation in the family between parents and uncle (mamak) help to form better parenting. This provides many benefits for the family, but it is also very complex because both the parents and the uncle (mamak) must simultaneously carry out their roles as caregivers, and maintain relationships with each other [66-68].

4.3. The Influence of Community Environment on Adolescent Behavior

Community is one of the educational environments that strongly influence the personal development of adolescents. Besides the family, the community is the second natural environment known by adolescents. They need support from the surrounding environment in their development process [69, 70].

Based on several research findings, it is evident that the community environment influences the character of adolescents. Relationships with peers also influence the character of adolescents. However, some adolescent behaviors are not influenced by their peers [71, 72].

Based on the output path coefficients shown in Table 5, the variable of community environment had been found to exert a negative and insignificant influence on adolescent behavior. This is evidenced by the t-statistic value of 0.662, which was less than 1.96, and the significance was set at alpha 5% (P-value < 0.05). Thus, the hypothesis accepted H0.

The findings of this research reveal that the community environment does not have a significant influence on the behavior of adolescents, because the development of adolescents' personalities is mostly influenced by the family environment. Therefore, the community does not have a significant influence on adolescents' behavior.

4.4. The Influence of Community Environment on Matrilineal Parenting

Matrilineal parenting that involves parents and uncle (mamak) in the family is strongly influenced by geographical area, norms and culture of the local community, social partners, activities in the community, and the mass media [73-74]. Likewise, the lifestyle in the community also influences parenting [75].

Based on the output path coefficients shown in Table 5, the variable of community environment had been found to exert a positive and significant influence on matrilineal parenting. This has been evidenced by the t-statistic value of 33.840, which was greater than 1.96, and the significance was set at alpha 5% (P-value < 0.05). Thus, the hypothesis accepted H1. In other words, the community environment had been found to have a positive influence on matrilineal parenting.

Parenting is related to the ability of a family or household and community to provide attention, time, and support to meet the physical, mental, and social needs of growing children. There are three parenting patterns, namely authoritarian, authoritative, and permissive parenting. Each of them affects the emotional, behavioral, and mental aspects of children [76].

4.5. The Influence of Matrilineal Parenting on Adolescent Behavior

The parenting styles received by children influence their behavior and personality [25]. Parents are the most basic role model in the family. If parents behave violently in the family, then children tend to imitate it. Likewise, if parents behave well in the family, the children also tend to behave well. Adolescents receive teachings and instructions given by parents [75]; therefore, the support of parents is favored by adolescents in their development. In matrilineal parenting, parenting is not only provided by parents but also involves mamak [51].

Based on the output path coefficients provided in Table 5, the variable of matrilineal parenting had been found to have a positive and significant influence on adolescent behavior. This has been evidenced by the t-statistic value of 12.858, which was greater than 1.96, and the significance was recorded at alpha 5% (P-value < 0.05). Thus, the hypothesis accepted H1. In other words, matrilineal parenting had been shown to have a positive influence on adolescent behavior.

CONCLUSION

Based on the research findings, it can be concluded that (1) family environment has a positive and significant influence on adolescent behavior; (2) family environment has a positive and significant influence on matrilineal parenting (3) community environment does not have a positive influence on adolescent behavior; (4), community environment has a positive and significant influence on matrilineal parenting; and (5) matrilineal parenting has a positive and significant influence on adolescent behavior. Therefore, matrilineal parenting and family environment greatly determine the development of the adolescents' behavior. When parenting styles and family environments are good, the behavior of adolescents becomes stronger. Otherwise, when parenting styles and family environments are not good, the characters of adolescents become weaker. Thus, the cooperation of a mother, a father, and mamak in matrilineal parenting is very helpful to form strong adolescent characters.

RECOMMENDATION

The family (a mother, a father, and mamak) is expected to apply matrilineal parenting by collaborating in providing guidance to adolescents and creating a good family environment, thereby strengthening the behavior of adolescents in facing the wider community environment. Since this research involved a subject limited to mothers, the researchers provide recommendations for further research on the behavior of adolescents with broader research subjects.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

The West Sumatera provincial government approved this research with recommendation number 8.070 I 1179-PERIZDPM&PTSP/XIll2019.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals were used in this research. All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

The participants participated voluntarily and provided their informed consent.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors want to express their gratitude to the supervisors for their guidance that helped to complete this research. Furthermore, the authors appreciate the assistance and cooperation of mothers who participated in this research. The authors would also like to thank the West Sumatra provincial government for providing research permits.